Marshall McLuhan — the great assessor of the impact of mass media on our lives — wrote an essay in 1963 called “The Agenbite of Outwit.”

He said that, when humankind implemented the telegraph in 1844, it radically altered the state of human consciousness because it had projected its central nervous system out onto the world. Every conscious neuron was thence connected by immediate-information-giving utilities to every other.

McLuhan was aware that human inventions involved extensions of the body into space: the wheel an extension of the foot; the hoe, the arm; clothing, the skin; and the book an extension of the eye.

But with humankind’s global connection through its nerves, the axis of reality shifted radically; it created benefits of course but it also created a new set of obligations because no neuron could deny the presence of every other.

The late great contemporary composer John Cage took a liking to these ideas. It was not that they flipped reality on end but more that they presented opportunities for living more sanely. They redefined the concept of sharing so that it now includes sharing not only the benefits but also the burdens of others — fully supportive of the axiom: People are happier when dog no longer eat dog.

In his classic, “A Year From Monday,” Cage says (and I paraphrase, you can see the original on Page ix): it is now incumbent upon humankind to implement globally the disciplines people traditionally practiced to be at peace, at one with themselves — meditation, yoga, psychoanalysis, and every related modality.

When such disciplines are practiced globally people recognize that others are not threatening and greedy by nature. They are better able to see the needs of others (people are more inclined to speak of them) and moved to take steps to meet those needs without resentment or derision. Such is how an effectively working planet-wide central nervous system operates.

For a long time, Cage was interested in producing a list of utilities that connect us to each other (e.g., the telephone, radio, Internet) whereby we come face to face with every language, custom, and ritual situated along the spectrum of humanity.

In “Agenbite,” McLuhan said that, since the world contracted to the size of a tribe or village where everyone knows what’s going on everywhere, the human community feels compelled to participate. Participation is the democratization of happiness.

Understandably McLuhan has long been thought of as one of the inventors of “global village” but a village free of zenophobia. Zenophobes fear diversity, it contradicts assumptions about self and other that thrive on a divide-and-conquer ethic.

Anyone interested in anthropology knows that people living in pristine tribal cultures — there are a million studies on it — find it impossible to think of themselves as an “individual” or “independent” operator.

Of course “primitives” recognize differences — some folks are faster, smarter, stronger, and more efficient in amassing prized money-shells — but the faster do not tax the slower to enhance their prestige. A consciousness wired to every other induces genuine humility and compassion.

For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church tried to promote global connectedness through the concept of a “mystical body” asserting that through Jesus all Christians share a mystical, spiritual bond that cannot be broken.

And Alexander the Great proposed a similar idea in his “homonoia,” a universal union of hearts, a “brotherhood of man” but, in his brotherhood, brother does not share the burden of brother.

Though we continue to reap the benefits of a fully-operative global nervous system, the human community still has not faced up to the task of putting flesh and bone on those nerves, that is, of creating a political economy designed to meet the needs of all, one that fits the complex of nerves.

And needs-based means providing not only full health care for everyone, from the day we’re born to the day we die, but also housing, daily sustenance, old age care, the works — the opposite of a deserts-based, dog-eat-dog, tribal mind.

Thus the potential for achieved well being is no longer limited to Christians or Macedonians or any other sect but extends to every physical, neurological, consciousness in our global home.

Disbelievers in this connectedness are at least willing to acknowledge that what happens in China (and Mexico, Vietnam, and Japan) affects the quality of our lives in the United States. They acknowledge globalization but only in so far as it relates to money, trade, power, and deserts-based benefits.

Otherwise their battle cry is for walling off the self and nation from what exists on the other side of the synapse and for siphoning off “differences” among populations into “ghettos.”

This is nervous-breakdown thinking and explains why at any moment some group somewhere can rise up and terrorize the world, claiming their dreams were shattered through demonizing, exclusionary, needs-denying practices.

Quite astoundingly, two of the 2016 presidential candidates in the United States are calling for revolution: one for “political revolution,” the other for a guilt-free battering-of-the-weak-without-reprisal revolution based in an ideology that stigmatizes difference.

The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard predicted this would occur when his “The Concept of Dread” appeared the same year the telegraph was born. He was addressing the dread of connectedness, the dread of facing up to a needs-based political economy that being linked neurologically requires.

Pope Francis recently said that people who wall themselves off from others, who classify and divide, are destroyers of the mystical body and cannot call themselves Christians. They tear away at the limbs of a universal needs-meeting body.

Which brings us to the true function of the computer. People might use the machine to Google cheap flights to Spain or find a good house at the shore but the computer exists primarily: (1) to inventory the needs of every neuron in the cosmic system; (2) to inventory every available worldwide resource (every kind everywhere); and (3) to find the best way of getting what’s needed to those in need without charge or delay.

We do know of course that in every Eden people steal, cheat, rob, and raid your cache — sin is a given — but in the meantime, in this era of our neurologically-connected needs-based revolution, every person on the planet is treated like the richest person on earth.

Now that’s a revolution of dread.

Location:

Circa 1935: Dennis Sullivan’s family visited Coney Island and had this portrait taken. His mother is the woman in white, third from the right in the second row, and her mother is in white all the way to the right. Four of the author’s aunts and one uncle are in the photo as well as lifelong family friends.

The presidential candidates are out on the trail again and the topic of “family values” is back on the agenda, if only slightly. I like that. I like talk about the family.

When I’m in conversation with folks at a coffeehouse or casual-dinner setting and the topic of family comes up, I invariably ask the person who’s sallying forth about it: What does your family stand for? And invariably I get: What in the world does that mean?

And I say, well: Do you come from a creative family or maybe a family that likes to laugh and, when it does, the pain of life is relieved somewhat? Does your sense of humor provide perspective when times get rough?

“What does your family stand for?” is a kind of Rorschach test. Someone connects with one of the inkblots and says: Oh, look, that’s me, there’s my family, we’re into power; we love money; we thrive on prestige, privilege, and things elite. Our Sermon on the Mount is: Do unto others before they do unto you and then cut out.

There are people who say their family has believed (and practiced) for generations giving an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay. They say they’re “into” justice, standing up for policies that meet the needs of everyone.

Asked to give an example they say: Well, every person on Earth has a right to full health care from the day they’re born till the day they die, no exceptions. And when you ask why they say: Because Health and Healing are inalienable rights.

I’ve talked to people who come from laissez-faire families who care about nothing and it makes no difference; they say they want to keep stress down.

With respect to “What does your family stand for?” it should be pointed out that this is not a niche or boutique question designed for a certain few. It pertains to everyone, and anyone interested in bettering personal development and mental health must answer it, and do so through serious self-reflection. Become an Ancestry.com for the genealogy of morals.

Secondly, the question in question is not academic because the family — and that includes everybody who has a say in it — wills you something. And you’re willed not just proteinic DNA but social DNA as well. In some cases, it means the row assigned you is easier to hoe; in others, it entails seeing a therapist for 30 years to peel off layers of familial gunk.

Thus, answering “What do I stand for?” has to do with finding out what you were “willed” and how your legacy affects your standing in the world. It’s a sad game because it involves our forebears saying: Here’s a little keepsake, I hope it works out for you — we are never consulted.

Some people get left holding the bag. They’re willed racism, hating black people and Jews and demeaning women, Muslims, and people whose sexual being requires complex solutions for well being.

If a family’s traits are based in aggression — perhaps from a fear of scarcity — those traits can erupt when the family comes together. Every year, hordes of articles are written during the winter holidays (Thanksgiving, Christmas, et al.) advising people how to emerge from family encounters with their hide in tact.

The great Irish lyrical poet, Michael Hartnett (1941-1999) has a poem called “That Actor Kiss,” which speaks to his relationship with his father especially during the father’s last days.

His father is in a hospital or nursing home and Michael, as he’s looking at his father in bed, leans over and kisses him; later over a drink he realizes that was the last kiss he ever gave the man, and also the first.

He says the shame is that that “kiss fell down a shaft too deep/to send back echoes that I would have prized.” And what did the father leave him?

(he willed to me his bitterness and thirst,

his cold ability to close a door).

Hartnett says he was given an acerbic tongue based in loss, a fondness for the drink, and a revenge that gets even with people by shunning them.

I teach, maybe “facilitate” is a better word, a course at the Voorheesville Public Library called “Writing Personal History for Family, Friends, and Posterity.” People in the group write stories about what they were willed, where it’s gotten them, and how they feel about the deal. It’s self-analysis and writing your own obituary rolled into one.

One inventive member of the group, Jim Corsaro, says in a story “Family Closets” that his garrulous Italian-American family in Niagara Falls were forever gabbing, talking about everything under the sun.

But he said he never heard a word about his brother being gay, which everyone had to acknowledge when he died of AIDS in a far-off land. Jim said he got the job of telling his mother about the death and the way his brother died. Much to his surprise his mother said she always thought her son was gay.

But what kept the family from acknowledging a sexuality that was different from theirs (presumably) and required a dose of empathy?

In conjunction with the publication of his memoir, “But Enough About Me,” the actor and movie star Burt Reynolds said growing up he always said his father was his hero but when Burt came to be an actor the father kept saying acting was for sissies. Plus he would not acknowledge his son was a going concern and, no matter how big Burt got, he refused to see him as a “man.”

As in the case of the Corsaros, Burt’s father could not stretch to meet the unique needs of a kin. Their scales of justice were skewed, unbalanced, exclusionary, discriminatory, callous — and toward a son, a brother, someone they once loved as a child.

Someone told me recently that if he starting talking about “What does my family stand for?” he’d wind up writing a book. And I said: Well, what’s holding you back?

Location:

In the Fall of 1957, the ABC television network aired a new game show, “Who Do You Trust?” It was a follow-up to a show that ran the year before, “Do You Trust Your Wife?”

In the new format the host, a young Johnny Carson, gave a contestant a category of questions and told him he was going to ask a question from it. The man had to decide whether he would respond or wanted to call his wife (waiting off stage) because he trusted her to know that part of life better.

The show could have easily been called: “How Well Do You Know the One You Love?”

Such shows spark viewer prurience because, as the contestant is deciding what to do, the viewer is wondering what he would do in the situation, that is, how well does he know his own wife?

A postmodern version of the show — in societies where people often arm themselves with automatic weapons and head to a movie theatre or holiday party to blow people to smithereens — might be called “How Well Do You Know Your Neighbor?”

Unlike the prototype “Who Do You Trust?” where winners walk away with a few dollars, the neighbor show is high-stakes stuff involving light-flashing ambulances and emergency rooms filled with bloody limbs.

Of course what comes to mind is the mass killing that took place in San Bernardino, California earlier this month when 28-year-old Syed Rizwan Farook and his 29-year-old Pakistani wife, Tashfeen Makik, went to Farook’s place of employment and “took out” 14 and sent more than 20 in emergency vehicles to the hospital to have their discombobulated bodies made whole again.

In terms of a game show, what the families knew about those folks is enigmatic at best. Nobody saw they had lost their minds to the belief that violence is an efficacious problem-solver — called “radicalization.”

If the relatives were on the game show “Do You Know Your Neighbor?” or “Do You Know the Ones You Love?” they’d have walked away with nothing while the community had been assigned the task of picking up mops and pails to wash away the stains of blood.

Farook’s brother-in-law, stunned by the event, said he was “baffled.” He said Farook was a “good religious man,” “just normal,” “not radical”; he and his wife were a “happy couple.”

When Farook’s sister, Saira Khan, was asked whether she noticed anything, her eyes glazed over, so soaked in disbelief was she. She said the couple was married, they had a child!

Feeling guilt over what occurred, she told CBS interviewer David Begnaud, “So many things I asked myself. I ask myself if I had called him that morning or the night before, asked him how he was doing, what he was up to. If I had an inclination, maybe I could have stopped it.”

“Inclination” is the operative word, which means “I knew nothing.” In response to her statements the Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump publically called her a “total liar.”

But the collective’s pool of predictive measures told us nothing either:

— 1. Neither person had a criminal record;

— 2. Neither was on a government terrorist watch list; and

— 3. The government had no concrete evidence (inkling) that something was going on.

Of course in retrospect, when 150 million FBI agents are put on the case, a few critical facts will turn up, such as those folks were engaged in big-time subterfuge (advocating violence as a problem-solver) for quite some time.

Though government officials are not allowed to take part in our game shows, we have to admit the FBI would score high on a show called “We Know a Lot About Your Neighbor — Retrospectively!”

We have to laugh at the “profilers” (sadly) who people the television screen after such bloody events, boldly stating that we need to be on the lookout for this or that. But, if their prediction tables are so good, we’d see scores of suspects being arrested while you’re reading this.

A headline in the Jan. 16, 2015 edition of “The Atlantic” reads: “To Reduce Gun Violence, Know Thy Neighbor” with the tantalizing subtitle, “How a sense of community can help stop a bullet.” The premise, of course, is a truism: If you know the people around you, you have a better chance of knowing what’s going on around you.

The author of the article, Andrew Giambrone, points to a recent study funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program on “neighboring” where the researchers found that a majority of their interviewees said they knew little about what went on in their neighborhood.

Scads of books and articles have been written on the loss of “social cohesion” and “social capital” — “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community” jumps to mind first — the glue that holds the species together, the collective wherewithal we bank on to move us into the future with minimal blood and violence.

With all the talk these days about building walls — physical and psychological — around racial, ethnic, and religious groups we want to keep at nation-boundary length, is it not feasible that members of some communities, worried about whether newcomers into their neighborhood are latently violent, will pay real estate agents to administer a battery of psychological tests to screen out the potentially violent?

If we’re ignorant about the current people we walk among, perhaps we can classify potential neighbors into the “good,” the “bad,” and the “ugly.” A kind of psychological redlining in the interest of building walls around our worries.

In a few hours, the New Year will be upon us. In some quarters, the champagne will flow like mad as revelers waltz across the ballroom floor subconsciously wondering how different things will be in 2016.

Me? I’m going to do two things. First I’m going to sing the traditional anthem, “Auld Lang Syne”:

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and never brought to mind ?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and auld lang syne?

For auld lang syne, my dear,

for auld lang syne,

we’ll take a cup o’ kindness yet,

for auld lang syne.

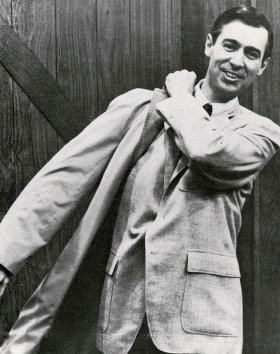

And, while I sing this sad reflective song, I’ll raise a cup of kindness and give thanks for the collective good will and tenderness that have brought us this far. Then I’ll sing a wassail song under the guise of the famed Mister Rogers.

In the cider-producing parts of western England this time of year, neighbors sing and brandish toasts to awaken their apple trees to scare away the evil spirits that threaten loss in the harvest to come. Mister Rogers wassailed every day his program aired in hopes of bringing forth a crop of worthy neighbors.

Perhaps you’d like to sing along with me:

It's a beautiful day in this neighborhood,

A beautiful day for a neighbor,

Would you be mine?

Could you be mine?

It's a neighborly day in this beautywood,

A neighborly day for a beauty,

Would you be mine?

Could you be mine?

I have always wanted to have a neighbor just like you,

I've always wanted to live in a neighborhood with you.

So let's make the most of this beautiful day,

Since we're together, we might as well say,

Would you be mine?

Could you be mine?

Won't you be my neighbor?

Won't you please,

Won't you please,

Please won't you be my neighbor?

Eso es todo, no hay más. ¡Feliz año nuevo!

When I was 12 and an altar boy at St. Mary’s of the Assumption Church, on my way to serve midnight Mass on Christmas Eve, I looked intently at the winter sky in search of the Star of Bethlehem.

I learned about the Star in catechism class and grew to believe that it returned every year and that, finding it in the darkness of night I, like the Magi of the first Christmas, would find the heralded child born in a manger.

The Christmas carol, “We Three Kings,” which my family sang and was played incessantly on the radio, said so:

O star of wonder, star of night,

Star with royal beauty bright,

Westward leading, still proceeding,

Guide me to thy perfect light.

“Still proceeding.” It meant the star came every year for every believer to see.

Within 10 years, in college courses on the Greek Scriptures (the New Testament), I was introduced to concepts such as “form criticism,” “redaction criticism,” and Midrash.

These methods exhorted that, in reading Biblical texts, it was critical to define the literary form and historical context of biblical passages in order to understand how the redactor (editor) shaped the narrative to express certain theological truths and reveal the purpose of his writing.

In the case of the narrative of Jesus’s birth, I found out there were two stories, one by Matthew the other by Luke, and that they did not put forth the same facts, in fact contradicted each other. I was disedified: How could there be a discrepancy in the Bible?

I was told the stories were parables — as Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan explain in “The First Christmas: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus’s Birth” — stories that might not be factual but nevertheless contain deep truths. A Joe Friday “Just the facts, ma’am” approach would not get at the truth.

In examining the Christmas stories critically, I had to conclude there was no manger, there were no swaddling clothes, there was no “star of night” to lead me to the “house” or “stable” — the two gospels differ on the location of the event — so I stopped looking for the Star of Bethlehem.

But there was a subversive quality to the new thinking in that, when the seeker of truth hears the angels (metaphoric) sing “peace on earth,” that person feels called to become a person of peace, which might include taking a stand against corporate, military, and religious institutions that initiate, thrive on, and profit from war.

In singing carols such as “Silent Night,” “O Holy Night,” “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear,” the person of conviction receives the truths contained in the Scriptural narrative and elects to chase away the darkness without fear, indeed becomes the announcing angel singing, “I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people.”

The great joy is that another soul has chosen to live a different kind of life, to create a different kind of world, one in which poverty and injustice are confronted and steps taken to eliminate them.

A while back, it struck me that that was what Dickens was talking about in “A Christmas Carol” — my favorite (and only) childhood book — when the Ghost of Christmas Present forces Scrooge to look upon two emaciated children, a boy called “Ignorance” and a girl called “Want.”

The spirit warns Scrooge, “Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom unless the writing be erased.”

But ill-sighted Scrooge could not accept personal responsibility for erasing the conditions that gave these children currency, exclaiming in write-off fashion: “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?”

As the night progresses, as lovers of the story know, the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come projects for Scrooge personal destruction that will occur — the death of Tiny Tim — without his involvement in the lives of others. Scrooge of course undergoes a transformation and becomes Tim’s “second father.”

The 19th-Century novelist Margaret Oliphant described this book of metamorphosis as “a new gospel.” claiming that it did in fact make people better.

“A Christmas Carol” came out in 1843 and reflected Dickens’s real-life experiences with the poor and downtrodden. The book’s plot was conceived during the author’s three-day stay in Manchester, England witnessing the poverty and human degradation inflicted on the “dregs” of the citizenry.

I do think it more than coincidental that during 1843 the first worldwide commercial Christmas card was produced. Inventor Sir Henry Cole commissioned artist John Callcot Horsley of the Royal Academy in London to design a card that people could send to family and friends to wish them Merry Christmas while reminding them of what the December birthday stood for.

In its own right, the card is a kind of gospel, a parable that tells a story far more complex than the cards bought, signed, and sent today.

In the Horsley original, a family has gathered together to offer a toast to the person looking at the card. The gathered friends are facing the recipient with their glasses held high looking not sad but not exuding merriment.

On the card, to the right of the family is depicted a woman with a child being clothed by a compassionate older woman standing above them, and on the left is a man serving food to an old person and a child dressed as commoners.

Let those who make distinctions between the sacred and profane play games that split the world in two. When I saw the card, I exclaimed: Look! It’s the Star of Bethlehem!

The star shines in the family greeting its loved ones with a cup of caring wine and in the reminders offered, left and right, about how to defeat Ignorance and Want.

It is a continuation of the parable of love found in the Greek Scriptures as well as in the parable of transformation found in “A Christmas Carol” where angels and spirits respectively sing strains of peace and good will.

And such transformation is not the property of a particular sect of believers; it belongs to every soul who faces the dark night of winter. It might not contain a manger or swaddling clothes or shepherds watching their flocks beneath an open sky but it does reflect a world where the pain of those in need has been taken into account and eased, if only slightly, by human beings committed to angelic peace.

Under such circumstances, the darkness of death hasn’t a leg to stand on because it’s a death-defying birthday, a birthday that belongs to every soul far and wide who looks up in the midnight sky in search of the Star of Bethlehem.

The first chapter of Graeme Green’s “The Power and the Glory,” published in 1940, tells of a certain Mr. Tench who as a boy felt impelled to become a dentist like his father after finding in a wastebasket a discarded cast of a patient’s mouth.

The family tried to dissuade the boy from his fascination with the “toy” by offering an Erector Set in trade but the boy refused. It was too late, Greene says, “fate had struck,” and then with what is often quoted with regard to having a calling in life he adds: “There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.”

The door of course is the door to the unconscious. When it opens, the initiate — of any age, and it opens more than once — receives a vision, hears a voice, telling him what path to take in life, how to situate himself in the world. And the recipient has no choice but to obey unless he wishes to be haunted by guilt and regret for becoming a self he was not meant to be.

The haunting persists, the Swiss writer Alain de Botton says in “The Real Meaning of Your ‘True Calling’” (“O, The Oprah Magazine,” November 2009), because one’s calling is connected to such primal questions as “Who am I?” and “What am I meant to be?” Elsewhere he says, pessimistically it seems, the best a person can hope for is to see his talents and aptitudes find a receptive home in the world.

Of course there is grave difficulty in talking about “calling” or “vocation” today because formal religion coopted its usage centuries ago, claiming there is only one authentic voice and that is God’s, all others, as some claim, are the work of the Devil. Thus to have a calling has come to mean becoming a minister, a nun, a priest, or a similar church functionary.

It’s not that calling in life is not a religious concept; it is, but the larger community has been stripped of its stake in it. And yet just a few weeks before his death, on Aug. 30, 2015, the great neurologist Oliver Sacks spoke in The New York Times of his calling.

Involved with patients subject to the weirdest neurological disorders imaginable, Sacks said he felt “a mission to tell their stories . . . I had discovered my vocation, and this I pursued doggedly, single-mindedly” (with no help from others).

Speaking of calling this way, we see it means having a destiny the outline of which comes in the vision or dream when the door opens — and may direct the person to do something monumental as relieving the suffering of others.

Getting hooked up with one’s dream was part of every American Indian’s life growing up. The community did not wait for a door to open; they shook it open. They brought the aspirant to a remote place where, through fasting and ingesting concoctions to disorient the mind, he waited for a dream to come and project his destiny. And the Indians made clear that this was not the work of a spiked imagination.

When the Moravian missionary John Heckewelder, who lived among and near the Delawares (Lenni Lenape) for more than 30 years, saw an Indian engage in deeds of extraordinary courage, he inquired of the person how he knew he would be able to handle such things. The response was that the “tutelary (guardian) spirit” that he had received in a dream was his source of strength, his guarantor of safety.

In his “An Account of the History, Manners, and Customs of the Indian Nations, who once inhabited Pennsylvania and the neighboring States,” published in 1819 — every line of which is worthy of attention — Heckewelder says initiates “were put under an alternate course of physic and fasting, either taking no food whatever, or swallowing the most powerful and nauseous medicines, and occasionally he is made to drink decoctions of an intoxicating nature, until his mind becomes sufficiently bewildered, so that he sees or fancies that he sees visions, and has extraordinary dreams, for which, of course he has been prepared beforehand.”

George Henry Loskiel, another Moravian clergyman who lived among the Indians in Pennsylvania, says in his equally-classical “History of the United Brethren among the Indians in North America,” printed in 1794, that the young man who has not received his calling becomes “dispirited and considers himself forsaken by God, till he has received a tutelary spirit in a dream; but those who have been thus favored, are full of courage, and proud of their powerful ally.” And God here means unbounded authentic inspiration.

In 2006, I delivered a paper at the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology in Los Angeles, “To Have a Calling in Life: A Human Antidote to Growing up Absurd And, For Those Involved in the Criminology-Related Disciplines, A Sure Method of Delinquency Prevention.”

I told the gathered that I saw more than a few parents tell their kids to be their unique selves, to find their unique place in life, to do what they feel called to do but their tone said: Be a success which, when questioned about its meaning responded: Court fame, get into power, do unto others before they do unto you, be successful for yourself, it’s a dog-eat-dog world. You have to decode the texts in these messages but the meanings are there and are almost always dressed in the same nuance.

In his essay “Why I Write,” George Orwell — “Animal Farm” and “1984” do not scratch the surface — says that, if a person had a choice, “One would never undertake such a thing [in his case being a writer] if one were not driven by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.”

As Greene said: Fate strikes and it’s case closed.

In 1902, the German poet Maria Rainer Rilke received a now highly renowned letter from a 19-year-old soldier, Franz Xavier Kappus, along with a bevy of poems, asking the poet to look at them and tell him if he had something going on.

Not so matter-of-factly Rilke says the poems lack a “style of their own.” He avers, “You are looking outside yourself, and that is what you should most avoid right now. No one can advise or help you — no one.” Except maybe a tutelary spirit who comes bearing a destiny dressed in a dream?

In his search for the essence of life, his continued calling, the great Spanish mystic Juan de la Cruz spoke of calling as involving a dark night of the soul but one in which all questions are answered. “On that glad night/in secret, for no one saw me,/nor did I look at anything/’ he says, “with no other light or guide/than the one that burned in my heart./This guided me/more surely than the light of noon . . .”

Years ago, I saw glimpses of a calling during discussions of soccer scores and Mel Brooks at dinner and more so during the boy’s periodic redition regarding his station in life. I listened because I knew such things are a matter of life and death.

Philosophy, the Queen, is at the center of the circle, surrounded by the seven liberal arts — grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy — in “Philosophia et septem artes liberales,” Latin for “Philosophy and the seven liberal arts.” The artwork is from the illuminated encyclopedia, “Hortus deliciarum,” meaning “Garden of Delights,” compiled by Herrad of Landsberg, 12th-Century abbess of Hohenburg Abbey in the French region of Alsace. The encyclopedia was used by young novices at the abbey and is thought to be the first written by a woman.

I would like to make a case for the study of the liberal arts in higher education but the deck is stacked against me.

The Internet is full of sites warning against academic money-losers and the arts and their literary entourage sit atop the list. Championing the liberal arts to bottom-line thinkers is like waving a red flag in front of a bull or more correctly watching the bull walk away with disinterest.

Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce issued a report this year, “The Economic Value of College Majors,” and among the disciplines resting safely in the food-stamp bin are: drama and theatrical arts; art and music; theology; studio arts, human services; language and drama education; and social work — never mind Greek and Latin (they died with Caesar) — in short, all the disciplines that feed the soul and help aspiring students frame a holistic vision of life.

Ranked at the top of the big-ticket diplomas in the report are: petroleum engineering ($135,000); pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences ($112,519); metallurgical engineering ($97,743); mining and mineral engineering ($97,372); chemical engineering ($96,156); and electrical engineering ($93,215).

It’s a riff on the old “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” joke and the answer is: engineering, engineering, engineering, and making the pills to dull the aches that living in a drum breeds.

The Georgetown report says early-childhood education majors — prepped to guide (not “lead” as their professional protocol asserts) kids 2 to 5 with the Piaget or alternate instructional methods — average $39,000 a year, which is little more than the presently-suggested upgrade in the minimum wage of $15 per hour.

This is not to say that early-childhood education is a liberal arts discipline but it can be when education is studied historically and in context where questions are asked like: How would Socrates handle a classroom in the city of Albany’s high school today? Would he reach for the hemlock once the kids saw his toga?

The majors that continue to remain popular among students are: business management and administration; accounting; general business; and nursing which means, QED, that Truth and Beauty, to cite Rodney Dangerfield, get no respect much less Truth and Beauty’s love child, Justice.

Is it not a sad irony that gold mined in the soil of the Earth is more highly prized than the gold sitting in classroom seats, never mind that seated behind the desk, those who guide or direct or teach or prime — pick your term — the kiddos for adolescence and adulthood.

The politically conservative columnist for The New York Times, David Brooks, has spoken with fervor in favor of the liberal arts — of self-reflective study that nourishes the soul — but a conflicted Brooks seems unable to shake himself free from a political-economic ideology that refuses to give the liberal arts equal footing in the marketplace.

He says he admires the saintliness of the modern social justice gadfly Dorothy Day — the pacifist anarchist who started the Catholic Worker Movement in 1933 — but refuses to accept, no, will not acknowledge, Day’s political economic stance on justice that caused civil and religious authorities much consternation. He stacks the deck against a holistic view of thinking (and living) that his beloved liberal arts are said to foster.

When the earnest student peruses Aeschylus, Arthur Miller, Dante, James Joyce, Dostoevsky, Emily Dickinson, or experiences the music compositions of John Cage and the dance sequences of Merce Cunningham, she sees the dangers of living a schizoid life and how such a life grates on well-being — though the liberal arts have never been guarantors of happiness.

And yet the liberal arts remain as contemporary as any course of study even when reflected in the lives of the ancients. The insights of sages east and west serve as a sword for cutting through the insulating jibber-jabber of any age. The aforementioned Socrates said that: No person desires evil; and no person errs or does wrong willingly or knowingly. Very intriguing postulates.

Whether one agrees with their assumptions or not, they can serve as an analytical sword for piercing the motives of, say, the Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump when he says that women are “slobs,” “dogs,” “pigs,” “bimbos” and then avers “I cherish women.”

This is a different kind of divide from which Brooks suffers but it shows a person in conflict over the value of Truth. The curse of the House of Atreus shows there is a price to be paid for trying to inhabit two worlds simultaneously and making believe you’re whole.

And this curse can be seen spilling over into the modern family as an exasperated, despairing Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) tells his brother Charlie (Rod Steiger) in “On The Waterfront” that it was he, Charlie, his brother — not some ruthless mobster — who destroyed his career, indicating that familial death-like treachery persists among us.

How does a brother respond to: “You don't understand. I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am, let’s face it. It was you, Charley [my brother, who destroyed me].”

The art of cinema as well as dance and music and literature exposes the student to Truth, Beauty, and Justice with bold and ineluctable lessons and helps the true aspirant develop a well-thought-out and meaningful “philosophy of life,” which is more essential these days than ever.

Since 1966, the Higher Education Research Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles has asked in its survey of first-year college students about the importance of school in developing a sound philosophy of life.

As Fareed Zakaria points out in his recent “In Defense of a Liberal Education,” in 1967, eighty-six percent of the first-year students said college was important for “developing a meaningful philosophy of life” but a year ago, in 2014, only 45 percent of students thought it was.

Has the “American mind” officially closed down as Allan Bloom asserted in his controversial 1987 best-seller, “The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today's Students.” It has (but not for the reasons Bloom asserted).

Wellesley College, one of the bastions of liberal arts education since its inception in 1875, has not backed off of but doubled-down on its commitment to the liberal arts in the 21st Century.

Its website says Wellesley is addressing the current challenge to the liberal arts “not by abandoning its belief in a liberal arts curriculum, but by working to ensure that students themselves understand — in the course of every learning challenge — that the disciplined thinking, refined judgment, creative synthesis, and collaborative dynamic [of the liberal arts]...are not only crucial to developing their leadership abilities, but are habits of mind that will serve them well throughout their lives, and be primary contributors to their success.”

Though such a commitment one can become Secretary of State, a screenwriter, president of a college, indeed a nationally-recognized editor of an award-winning newspaper — even its publisher some day — prying back open the American mind, weekly edition after weekly edition.

— Photo by Elinor Wiltshire

The Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh in 1963 visiting the stony grey soil of the family farm in Inniskeen, County Monaghan. He died four years later at 63. His often-quoted poem “Stony Grey Soil” has been read for many decades by every child attending elementary schools in Ireland.

Anyone who’s Irish or Irish-American or has an interest in the Irish soul, and even those who don a T-shirt on St. Paddy’s Day beaming “Kiss me, I’m Irish” while chanting, “The Wild Colonial Boy” over endless jars of porter, will want to include on this summer’s reading list Anthony Cronin’s nonfiction “Dead as Doornails” published by Dublin’s Dolmen Press in 1976.

In “Dead as Doornails,” the Irish poet, biographer, novelist Cronin has produced a literary page-turner that reads like a murder mystery. The mystery is the reader wonders how long the cream of Dublin’s literary crop — who hung out at McDaid’s, that famous public house at 3 Harry Street, for purposes of stout, whiskey, and conversation — can keep a step ahead of the Grim Reaper of drink.

Cronin chronicles seven writers and painters whom he knew and “hung with,” even living with some, and who were an integral part of the social and literary fabric of Dublin during the decades following World War II.

He shows the greatest affinity for the great Irish poet, Patrick Kavanagh; the great Irish poet, short story writer, novelist, and playwright, Brendan Behan; and the great Irish post-modern (a forerunner) novelist, Brian O’Nolan (aka Flann O’Brien, aka Myles na gGopaleen, when he wrote his column “Cruiskeen Lawn” for the Irish Times from 1940 until his death in ’66).

In the claustrophobic literary culture of Dublin, shaped by a scarcity of accolades and the ha’pennies needed to pay the rent, Kavanagh, Behan, and O’Brien went at each other with bladed tongues.

They acknowledged each other’s genius but rarely to each other’s face; their idiosyncratic suffering did not allow for convivial graciousness. Kavanagh, worst of all, could not stand a competitor of any ilk.

He eventually sold his friendship with an admiring and unconditionally supportive Cronin, for 30 pieces of ego. It’s painful to hear Cronin rue the loss of what could have been but there was a part of Kavanagh filled with bilious envy.

That the three refused to let each other up for air is evident in Myles’s column on Kavanagh’s “Spraying the Potatoes,” a poem published a short time before in the Times. Myles says, “I am no judge of poetry — the only poem I ever wrote was produced when I was body and soul in the gilded harness of Dame Laudanum — but I think Mr Kavanaugh [sic] is on the right track here. Perhaps the Irish Times, timeless champion of our peasantry, will oblige us with a series in this strain covering such rural complexities as inflamed goat-udders, warble-pocked shorthorn, contagious abortion, non-ovoid oviducts and nervous disorders among the gentlemen who pay the rent.”

Kavanagh, who came to the city from the family farm in Monaghan where he started writing rustic poems as a young man, knew that, when Dublin’s literary elite saw these words, many of whom graduated from Trinity or University College Dublin and considered themselves sophisticates, would relish Myles’s keeping a bumpkin in his place. The city smart-aleck Behan called Kavanagh a “culchie.”

But Kavanagh was able to escape the tag through a whole new order of poems that appeared in the mid-’50s typified by “Canal Bank Walk.” And his earlier rustic takes, such as “Stony Grey Soil,” “Shankoduff,” and “A Christmas Childhood,” have been part of every Irish child’s formation for decades. Every student from Dublin to Bantry has read his work and, should you meet one such in a pub some night, he will stand and recite with pride the full “Stony Grey Soil.”

Brendan Behan, openly gay and not bashful to talk about his exploits, came upon sudden fame when his play “Quare Fellow” was produced in Dublin’s Pike Theatre in 1954 though “quare” then did not have the pith it has today.

Originally called “The Twisting of Another Rope,” the drama chronicles the ignominies of prison life culminating in the execution of “the quare fellow,” a character never seen on stage. With respect to the demeaning insult of prison, Behan was writing from experience (see infra).

Born into a staunch republican family — his uncle was Peadar Kearney who wrote the “Irish National Anthem” — Behan left school at 13 to work in the family house-painting business.

At 16, he joined the Irish Republican Army and on a whacked-out whim conducted an unauthorized mission to blow up the Liverpool docks but the plot was thwarted. When the police found him heeled with explosives, he was sentenced to a borstal in the UK for three years. He wrote about his bid in “Borstal Boy,” which, when it appeared in 1958, became a sensation.

But, long before the book, a year after he got out of the borstal, in 1942, he was sentenced to 14 years for being involved in the killing of two detectives of the Garda Síochána. He was released after three years through a general amnesty that had been declared.

At McDaid’s and elsewhere Behan was always on, performing extended parlor pieces for the gathered crowd and even an audience of one when there was only one to be had, so great was his undiminished thirst for admiration.

He was so vicious in his sallies against Kavanagh that, when the Monahan poet alone in McDaid’s or elsewhere saw him coming, he hid or left the premises altogether. Cronin witnessed these encounters, which he treats with alternating doses of mirth and sadness.

Brian O’Nolan, who had his own covey of friends in McDaid’s and nearby pieds-à-terre, was no less a part of the goings-on. For years, he paid the rent working as a civil servant while writing for the Times. When he was “forced” to retire and a scant government pension did not allow ends to meet — the daily slog of drink a major drain — he sought a job as a clerical worker at Trinity but was denied.

Fate is crueler than anyone knows because decades later O’Nolan’s works were taught at the university, principally “At-Swin-Two-Birds,” published in 1939, the novel some say was the first postmodern piece written and a classic still. The Guardian ranks it 64 of the 100 best of all time.

O’Nolan was not around to see the kudos. Drink took him at 54; Behan it got at 41; and Kavanagh, the ancient of them, at 63, his belching stomach rarely tamed by the box of bicarb he carried on his person.

Cronin’s high-Irish Ciceronian sentences in “Dead as Doornails” are a delight to engage at every subordinate clause. He tells a riveting story.

There’s time to get a copy and sit beneath an umbrella on the beach refusing to talk to anyone until you’ve seen how the flames of these bright lights of Ireland’s soul flicker and expire.

φαίνεταί μοι. If that’s Greek to you, you’re correct, it is. And if you detected they are the first two words of the great Seventh-Century, Lesbos-born, Greek poet Sappho’s Poem 31, you are correct as well. It translates “He seems to me . . .”

It is Sappho’s most famous poem, an epithalamium, a wedding poem sung for a bride on the way to the marriage chamber.

The poem — or more correctly song because Sappho plucked a lyre (barbitos) while she recited — is quintessential Sappho and deserves the attention of not only poets but every living soul since Adam and Eve because it touches the feelings of a heart experiencing loss of a beloved.

In Poem 31 the singer, poet, lyricist — it could be Sappho or a projected other — is expressing feelings of jealousy because a woman she loves has gone off and married someone else, a man. The loss is so great, the poet says, she’s broken out in a cold sweat and shaking, her symptoms so acute she feels dead.

This ancient torch song contrasts greatly with the same theme country music stations play every day of the year but Sappho sings with more authenticity, immediacy, and accuracy of feeling. The listener cannot escape experiencing the pathos of the singer, thus the poem becomes a mirror for the listener’s soul.

And while our lesbian poet reveals she is in the throes of death, she tells her story “slant,” as Emily Dickinson commanded, so the reader does not feel Sappho — or whoever the projected singer is — is one of those 19th-Century repressed “hysterics” who came to Sigmund Freud in hopes of jettisoning sorrow.

Sappho was among the first Western literary ancients to address the world in the first-person, and the first to do so with such outright candor, without shame or malice, which is what every human being beset by loss desires, especially when laced with jealousy.

Because of her depth of insight, the ancients adored Sappho. They said she was as great as Homer, calling Homer “the poet” and her “the poetess.” Plato called her the “10th Muse.”

Her image was engraved on coins in Lesbos; a beautiful statue honoring her was erected in the town hall at Syracuse; elegant vases depicting her plucking a lyre were cast only two generations after her time for which cultured, well-to-do Greeks paid good money to display in their homes. It may not be too much to say she was an ancient rock star.

When the Athenian statesman, lawmaker, and poet Solon heard his nephew sing a song of hers at a drinking party, so enchanted was he, legend says, he asked the boy to teach it to him. He said, once he learned it, he would be able to die.

Long-time fans of Sappho are elated these days because the bard is back in the news. Last year, Dirk Obbink, a papyrologist at the University of Oxford, revealed he had been the recipient — secretly from a private collector — of two previously unknown poems of hers: one about her brothers, the other about unrequited love.

The finding of the “Brothers” poem was especially lauded because it makes only the second complete poem we have of Sappho; the other is called “fragment 1,” a hymn to Aphrodite, where the singer beseeches the Greek goddess to aid her in her pursuit of a woman she’s after (religion as an aid to libido-satisfaction).

Scholars are indeed grateful for anything “Sappho” that comes along because 97 percent of what she did is gone; her extant work consists of little more than 200 fragments of poems, a considerable number of which amount to no more than a line or two. It’s maddening. The greatest shame is that cataloguers in the ancient library of Alexandria said Sappho had nine books of poems to her credit amounting to more than 13,000 lines!

Whatever happened? You will find it written all over the Internet that those verses vanished because Roman Catholic officialdom burned her in disgust. The Byzantine archbishop Gregory of Nazianzen and Pope Gregory VII are always mentioned as the sanctioning culprits, but there is no evidence to support condemning them.

It is known, however, that the Second-Century ascetic and Christian theologian Tatian in his address to the Greeks (Oratio ad Graecos) called Sappho "a whore,” a whore “who sang about her own licentiousness.” But that fellow must be relegated to nutdom because he said that marriage was the institution of the devil.

The reality seems to be that Sappho’s work fell on rocky soil in large part because she wrote in a difficult vernacular Lesbian-Aeolic dialect that differed from the lingua franca of Athens at the time, so later copyists selecting books to transcribe triaged her to the trash in the interest of time and limited translation skills.

A new translation of Sappho appearing last year by Grand Valley State University (Michigan) Professor Diane J. Rayor (with introduction by André Lardinois) titled “Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works” helps to assuage the ignominy of such (idiotic) shortsightedness.

Rayor’s efforts have been lauded in all the scholarly mags (Lardinois’s introduction as well) but the nuances of her translation keep being compared to those of the laser-minded Greek scholar and poet Anne Carson in “If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho,” which appeared a dozen years ago. Vis-à-vis Carson, Rayor always seems to finish second.

Sappho said a poet can sing about wars and all that tough-guy stuff but what matters most is where a person’s heart is. In Poem (fragment) 16 she says (Carson’s translation):

Some men say an army of horses

and some men say an army on foot/

and some men say an army of ships

is the most beautiful thing/

on the black earth. But I say it is/

what you love.

Because she came from Lesbos and had an abiding affection for women — though she was married and had a daughter — during the latter part of the 19th Century women whose feelings of love were directed toward other women began to call themselves “lesbian.” The Greek verb lesbiazein (to act like the women of Lesbos) has highly erotic connotations and those interested in divining them can check their Liddell and Scott rather than expect explication in a family newspaper.

Sappho was exiled during her twenties or early thirties — depending on her actual birth year, which ranges from 630 to 612 B.C.E. — at a time when Lesbos was undergoing great political turmoil but no evidence exists to suggest she was politically involved.

And the erotic themes she sang about were not outlandish in any way. That judgment came during the Hellenistic period (third/second centuries B. C. E.) when what she said was regarded as disgraceful for a woman.

For those interested in exploring the mansions of the human heart, Sappho is cherished all the more because her few remaining texts keep out of reach like the apple she sang about in Fragment 105A (Carson translation):

as the sweetapple reddens on the high branch

high on the highest branch and the applepickers forgot —

no, not forgot: were unable to reach.

But there is hope. Each unearthed papyrus, in which her words were sealed for over 2,000 years, enables the yearning heart to tiptoe a bit higher and just reach the sweet red apple of sapphic love.

Just as there’s a difference between baseball players and people who play baseball, so there’s a difference between gardeners and those who garden.

Those who say, “I think I’ll throw a few tomato plants in this year” are not “baseball players,” telling us in code they’re not interested in watching things grow. And, though differing at the genus-level, growing a plant is no different from raising a child.

Therefore I have rules and views about gardening. The first is: The way a person’s garden looks is the way that person’s inner landscape is, in shape and content.

When a garden is helter-skelter, that person’s mind is helter-skelter. Gardeners might be forever catching up on things that need to be done, but are never slipshod about what sits before the eyes.

Which means that, since each plant has its own growing needs to enjoy its stay on Earth, before growing a plant, the gardener finds out about it, especially wanting to know what other gardeners have said about it.

Growing kale is not growing potatoes or laying an asparagus bed and growing any sort of thing does not mean dousing it with Miracle-Gro. The gardener is, as the person who grows things is not, interested in fostering conditions that insure diversity.

And let me add that people who say they hate weeding are not gardeners. I am amazed at the number of weed-whiners, people who act as if they’ve been besieged by an unhealing rash on a sensitive part of their body.

First of all, weeding is healthful for gardener and plant alike. For the gardener, it’s meditative, restful, and contemplative. It slows the city in us down and curbs the ADHD in everyone.

When Cicero was defending the Roman poet Archias in 62 (BCE), he told the prosecutor Gratius why Archias was so important to Rome: “You ask us, O Gratius, why we take such great delight in this man. Because he supplies us with a place where our souls might be refreshed from the din of the marketplace, and our ears weary from its clatter find some peace of mind.”

Cicero could have been talking about weeding and gardening generally. Weeding refreshes the mind by allowing the ears to breathe freely; the process of thoughts-arising as we move from bed to bed instructs us in a hundred different ways.

And because the gardener is attentive to the livability-quotient of each plant he is ready to do battle with any being that diminishes it.

I’m not saying pull every weed as if you’re intimate with it — there may be large sections to clear — but that “killing a weed,” “taking it out,” “neutralizing it” with precision requires attentiveness to its demographics.

Some weeds burrow deep into the ground and taking off their heads breeds gorgonesque effects. They threaten like Arnold Schwarzenegger in “The Terminator”: “I’ll be back.” The gardener’s bible says: Know thy weeds; they will be back; be prepared.

The meditative aspect of weeding ought not be minimized. It induces endorphins. When the mind sees the cultivated plant more relaxed, freed from invading hordes, the gardener relaxes too, feeling that something has been done to promote livability (the plant’s and ours from its fruition).

Mutatis mutandis, in a day or two the freed plant will be less constrained and the vigilant gardener — a redundancy of course — will record that transition, if not in a book, mentally — in gardening terms indelibly.

A good training ground for learning this vigilance is starting plants from seed, maybe upstairs in your room after winter’s done. And not to decry the efforts of those who do “the windowsill thing,” lights are essential. It’s strange but plants are more accepting of our diversity than we of theirs.

Starting life from seed, the gardener learns how to make a home, how to hydrate, how to feed a being trying to get a leg up on life.

The great tomato aficionado Craig LeHoullier says in his just-released “Epic Tomatoes: How to Select and Grow the Best Varieties of All Time” (Storey Publishing) he feeds his seedlings nothing — contrary to the wit of most — because today’s potting soils are fully fit.

It’s a great book; if you are a tomato fan, get it, study it; I have problems with aspects of its design but the content is far beyond a 100-percent solid. He and Carolyn J. Male are the best there are, though she talks about tomatoes in a way that enraptures me.

The last thing I’ll say about method has to do with successive plantings. If green beans are a favorite (bush, say), you’ll need to plant a row every 10 days. I’m surprised at how many people treat growing as a one-shot deal.

And, in terms of planting lettuce, we have nearby greenhouses such as Gade’s and Pigliavento’s to get us an early start, so there’s no reason to buy lettuce from late May to late October — and infinitely better tasting than any store-bought.

And because the gardener refuses to let winter have the final say, toward the end of summer he counts back from the first frost and plants accordingly what the family likes, well aware that peas planted in early August present a different set of rules from those set out in April.

My father knew this; he was a gardener. He cut grass for rich people on weekends and took care of their flower beds but in our backyard, the size of a postage-stamp, he had fruit trees from upstate nurseries producing five kinds of apples on a single stem.

Once when I was a kid he asked me to go to the library with him at night; he had a horticultural question to review. I saw him in the reference room wrapped in silence seated before tomes on a large oak table in another world. He had an aura.

That day (night) I fell in love with gardening. I had my own when I was 18 and living in a monastery, a whole other world under a whole other set of circumstances, but his other-world devotion stayed with me.

Each day when I go to weed and support the conditions of life, in some way my father is with me and I keep in mind my first garden when my soul was freed from the din of the marketplace and my mind from the clamor of its death.

Oh, and for the record, any gardener I know is beyond happy to hear anyone say at any time, “I think I’ll throw a few tomato plants in this year.”

Anyone anywhere who has an interest in attending to living things we’ll take. That is the nature of us gardeners.

Location:

“Secularism is not an argument against Christianity, it is one independent of it,” according to George Holyoake, the 18th-Century British writer who coined the term. “Secular knowledge is manifestly that kind of knowledge which is founded in this life, which relates to the conduct of this life, conduces to the welfare of this life, and is capable of being tested by the experience of this life.”

It’s referred to as the “American secular movement.” What it refers to is the deep dissatisfaction of a fast-growing number of Americans with official religious values and the institutions that oversee their observance.

Identified among this disaffected horde of non-traditional believers — let us call them that for now — are atheists, humanists, freethinkers, agnostics, Unitarian Universalists, pagans, and other categories of not-formally-religious and non-theistic Americans.

A report published by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life in October 2012 said one-third of adults under 30 call themselves “religiously unaffiliated” and in the five years prior to the publication of that report the so-called “Nones” increased by a percentage point a year.

It’s a phenomenon that has not gone unnoticed or without concern and comment by a wide range of interested parties, and for a diverse set of reasons.

During the spring semester of this year, Douglas Knight, a professor of Hebrew Bible and Jewish studies at Vanderbilt University, is teaching a course called “Secularism” in which 29 of his colleagues are involved as guest lecturers to explore what’s occurring in the United States with respect to the shifting axis of moral values.

Four years ago, California’s Pitzer College established a once-inconceivable Department of Secular Studies where students can major in different aspects of “secular studies” under the direction of Professor Phil Zuckerman and his departmental colleagues.

In his 2014 “Living the Secular Life: New Answers to Old Questions,” Zuckerman set out to explore the parameters of the movement as well as divine how “believers of another sort,” defined as atheists or agnostics by traditional believers, can be as giving, and “self-sacrificing,” and committed to community as the most traditionally religious devotee. And without pietistic rigmarole.

Zuckerman makes clear that many people who have adopted humanist values and ethics do not have an ax to grind with (formal) religion. They are more interested in understanding the fact-based foundations of their own beliefs and how those beliefs continue providing support in meeting life’s challenges with propriety and dignity.

Paul Kurtz, the late professor of philosophy at the State University of New York at Buffalo, who is recognized as “the father of secular humanism” long ago warned that, when formal religious beliefs and practices no longer hold meaning for a person, that person’s aim ought not to be bashing them and the people who live traditional religious lives but rather to find out how to proceed with his or her own life with meaning.

In an interview with The New York Times in 2010, Kurtz said, “Most of my colleagues are concerned with critiquing the concept of God. That is important, but equally important is, where do you turn?”

In 2009, Kurtz resigned from the board of the Center for Inquiry, a group he founded, because he felt its derisive tone toward others was too contentious a path to follow.

When “the movement” is discussed, it needs to be pointed out that invidious comparisons are made at the outset by the way we speak about its diverse aggregate. It’s fruitless to talk about a-theists, a-gnostics, secularists, pagans and related nomina because they are inherently pejorative. With the use of the alpha privative in a-theist and a-gnostic, for example, the assumption is already made these “infidels” are second-class knockoffs of their real-deal theo-believing counterparts.

You will see articles such as: “Is goodness without God good enough?” and “Why Americans Hate Atheists.” Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas still retain articles in their constitutions that prohibit atheists from holding public office. Maryland’s requires a belief in God to serve as juror or witness. And it seems the long-standing shibboleth that no atheist will ever be elected President of the United States remains true to this day.

In his 175-page “Life After Faith: The Case for Secular Humanism,” published last year, Philip Kitcher provides a systematic and somewhat convincing argument for how a person can lead a moral life without God and formal religious beliefs and institutions.

I keep saying “formal” as in institutional because humanists do have beliefs based in religious values. And they are religious because “religion” comes from the Latin religare, which means to bind, to connect to the world around you.

And, even if we accept Cicero’s derivation that religion comes from relegere (to treat carefully) — the religiosi were those who took seriously all things pertaining to the gods — the aforementioned derivation holds true because we treat with care those to whom we’re bound. That is the nature of pietas.

But the issue of whether a person who lives a fact-based as opposed to faith-based life can live a moral life remains the wishbone of contention, so it is not surprising that Charles Darwin is turned to because through his work he reminded us that the basis of moral values is found in our social natures. He did say his “theory will lead to a new philosophy.”

I’m not here to provide an apologia for “secular humanism,” no, scratch the secular part, only to point out that our “social instincts” — a 19th-Century phrase that still retains legitimacy — allow us, as Darwin said, “to take pleasure in the society of [our] fellows, to feel a certain amount of sympathy with them, and to perform various services for them.”

And sympathy here does not mean the now-commonly-accepted feelings of pity and sorrow for someone suffering loss but more feeling bound to others in meaningful relationships that require care and, at the most basic level, reciprocity. Let’s call it an economic-based empathy.

And the tool that enables empathetic-bound-to-other-persons to proceed firmly on moral ground is the imagination. When I see your suffering, I imagine myself to be similarly situated, to be you, and I am moved to action.

I am also moved to envision new ways of being, of creating social institutions and societies in which suffering is eliminated. But, since pain and suffering are part and parcel of the human situation, that envisioning manifests itself through a society in which pain and suffering are responded to with loving care, in which structures are set up to meet human needs at all levels.

The great 20th-Century American poet Wallace Stevens in his poem, “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour,” comes up with the astounding “God and the imagination are one.”

That is what the humanists are saying, that they have in their power the tool to imagine all as one, and that that connectedness is the basis of all moral values (and subsequent remorse when harm is done), and that a Supreme Being of any sort seems if not inconsequential highly superfluous.