Dedicated to Steven White

One night in the middle of February 1927, when he was 34, the great Nicaraguan poet Alfonso Cortés woke with a start. He went to his father’s room and said something was wrong; he didn’t feel quite himself.

His father said it was probably something he ate and suggested taking magnesia. Alfonso went back to bed only to return a short time later saying, “No, Daddy, something very serious is happening to me, I am not able to sleep and terrible ideas are coming to me.”

It was his Rubicon; the family never forgot the day: February 18, 1927.

And to the whole family — father and sisters (the mother died two years before) — it remained a mystery as to what occurred. In his autobiography, “El Poema Cotidiano,” which came out in 1967, Cortés called it “a hair-raising vision like the one in a profound style the Prophet Job refers to.” He felt he’d been sent to Dante’s Hell.

In her biography of her brother years later, Maria Luisa Cortés, said the family referred to the event (and all the after effects) as “nuestra tragedia.”

How ironic that, as a 12-year old, his classmates at the Instituto Nacional de Occidente in León called Alfonso “el poeta”; now, at 34, his neighbors and fellow poets referred to him as “el poeta loco.”

No one doubted Alfonso had had a serious break with the reality he, his family, and fellow citizens of León, were familiar with. His close-knit family found themselves in a bind. They wanted their kin nearby but Alfonso needed supervision and sometimes restraint — he flew into furias, raging fits — but there was no insane asylum (manicomio) in León and the warehouse in Managua was out of the question.

So the family decided to keep him at home, devising a way to chain him up and then link the chain to a beam in the ceiling. Maria Luisa said, “The poet continued to be chained up in a room which had a view of the street, always with a thick chain which hung from a strong beam.”

“So as to provide more comfort for him,” she goes on, “a bed was set up on which he slept (the same wooden bed over which we had kept vigil for my mother); days later by his request a trunk was brought to his room containing books and manuscripts which he read every day. On a number of days after reading this he had a severe attack, he was completely uncontrollable, and began to rip the papers and destroy the books.” The furias.

But there were periods of quiet lucidity when the fam took the chains off so the poet could stretch and maybe strum his guitar. The room had a single window that he spent a good part of the day looking through, thinking about space and time and being and God.

Ernesto Cardenal, a major Nicaraguan poet in his own right — the saintly maestro died last month — grew up in León not far from where Alfonso lived. In a brilliant introduction to a book of 30 poems he put together in honor of “el poeta,” he says that, when he was 8, in 1933, he attended the Christian Brothers school just a few blocks from the Cortés home. He passed by it every day.

Cardenal said on one occasion the front door of the house was open wide so he could see at the end of a corridor a man chained to the ceiling. When he got home he anxiously inquired what was going on. The Cardenal family servant told the boy he had seen “el poeta loco.”

Cardenal said one afternoon, when the kids were playing in the schoolyard, Cortés, having broken free of his chains, ran amongst the kids, terrifying all — he hurt no one of course. The school authorities called the police; they came and took Alfonso home.

I won’t list the conjectures his contemporaries offered as to why Alfonso went mad — one said it was his mother’s death — but he told Cardenal at one of their many meetings later on that, when he started writing poetry at 7 or 8, his soul opened to literature and “locura” simultaneously.

Cardenal realized, “I believe in fact that literature and insanity had been one and the same thing for him ... Craziness and poetry begin with him from the same dark source … .”

There is considerable truth in what he says; anyone who has taken the time to look into Alfonso’s work, soon sees no difference between the poems he wrote when he was “sane” and those he wrote after se volvió loco.

When for strange reasons the family home was sold out from under them, the sisters finally agreed to take their brother to Hospital de Enfermos Mentales in Managua, where he was given shock treatments. There he remained until 1965 — 21 years, five months confined — when his sisters brought him back to León and cared for him at home. He died in 1969.

As millions of Americans care for themselves enclosed at home during this viral tsunami, I’m sure few will come upon Alfonso Cortés in the course of their extended reading. The irony is that they, all of us, are in the same situation as the mad poet; we too are confined by walls; we see the world through a little window.

In honor of his window and the life it wrought, Alfonso wrote a now-famous poem “La Ventana” — “The Window.” The first two lines read: Un trozo de azul tiene mayor/intensidad que todo el cielo.

“Trozo” in Spanish means “a bit” or “a piece of” and “azul,” as we know from azure, is blue. Thus the poem begins, “A little piece of blue”; of course, he’s writing about the sky he could see outside his window.

He then makes the extraordinary claim that that little patch of blue had more intensity than the entire sky (todo el cielo), the sky everybody else could see. Cielo is also the word for “heaven,” and for “marvel” and “delight.”

El poeta loco was telling the world outside his window that, within a tiny frame of life, one can experience a reality equal to, no, greater than, all the delights even heaven can offer.

The cynic will say: What! That guy was nuts! And I say, what do you see through your window and how does that match up with the greatest delights heaven offers you? Now of course it’d be: no coronavirus.

When he still lived at home, from time to time, Alfonso had to be taken to the hospital in Managua for tests. On the way in the car, he used to see out the window the magnificent genízaro tree of Nagarote, said to be 950 years old.

He needed to celebrate the tree. In an equally-famous poem “To the Historic Genízaro,” he writes: I love you, old tree, because at every hour/ you generate mysteries and destinies/in the voice of the evening winds/and that of the birds of dawn.”

As you, America, look at the world through your coronavirus-glazed window, what kinds of mysteries and destinies do the voice of the evening wind and the birds of dawn bring to you?

You’d better watch out; start talking that way and you’ll wind up in a manicomio.

Location:

Fearing he would soon die, the great American writer John Steinbeck packed his poodle Charley into a souped-up camper-truck — named Rocinante after Don Quixote’s horse — and started out to, as the Paul Simon song goes, “look for America.” It was 1960 and Steinbeck was 58.

Two years later, Viking came out with “Travels with Charley: In Search of America” in which Steinbeck shared with America the nation he and Charley saw. It became a best-seller; America was looking for a mirror to see herself in.

I like to believe Steinbeck’s trip was inspired by Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road,” which appeared three years before. Kerouac said he had been engaged in the same kind of activity; he too was looking for America.

In that truly American classic, Kerouac says he and traveling companion Dean Moriarity (Neal Cassady in real life), “embarked on a journey through post-Whitman America to FIND that America and FIND the inherent goodness in American man.”

They were looking for the America of dreams, the America in which neighbor offered succor to neighbor, mutual-aid-America, payment an insult.

In terms of genres, “On the Road” is part of the Beat literature generation, a movement that began two years earlier when Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” blew through America like a whirlwind.

His jeremiad begins: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,/ dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,/ angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.”

Ginsberg said his poem was “a lament for the Lamb in America,” the tender-hearted lambs America was feeding on like an angry Moloch. Like an Old Testament prophet, he said America needed to retrieve her tender heart, she needed to retrieve the tongue she was born with.

You can see why the Beats ruffled America’s feathers. They kept reminding America she was more or less than who she was but not who she was. As Paul Simon says, “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? Our nation turns its lonely eyes to you.”

The great American poet William Carlos Williams became, shall I say, obsessed with America too. He wanted to find America’s tongue, her idiom, he wanted to hear how she spoke, he wanted to see how her tongue was connected to her heart.

A small-town doctor for 40 years, Williams listened intently to his patients as they told about their pains and joys and daily peccadillos. Were they speaking American?

In 1950, New Directions came out with “In the American Grain” a book of essays where Williams described the lives of Daniel Boone, George Washington, Edgar Allan Poe, Abraham Lincoln, and others. wondering if each spoke American.

Williams wanted his work to serve as a mirror in which America could look at herself from time to time and assess whether she was being true to her dreams.

Some people have a hard time grasping the concept of an “American tongue”; they’re more familiar with Democrat-ese, Republican-ese, Socialist-ese, and all the other ese’s that are not American.

Some think the American tongue means the way New Englanders talk or families along the Bayou, not seeing that those are regional idiomatic linguistic patois derivatives, not the American tongue.

Some cynics say why worry about the American tongue, America is dead; you can’t hear someone who doesn’t exist.

The poets say there is something out there, something that looks like America but she — as Ginsberg would say — is howling because her tongue has been severed from her heart, a symptom of breakdown.

In 1831, the French government sent 26-year-old Alexis de Tocqueville to the United States to study American prisons with penologist Gustave de Beaumont; the pair took notes on the assigned institutions but de Tocqueville, like a socio-cardiologist, kept tapping into the American tongue.

He published his notes in a grand two-volume ethnography, “Democracy in America,” which he gifted to America as a mirror for her to look into.

At the very beginning of the work, de Tocqueville says, “Amongst the novel objects that attracted my attention during my stay in the United States, nothing struck me more forcibly than the general equality of conditions among the people.”

General equality of conditions. I assume that means equality was at the heart of the American tongue. He said it was having a “prodigious influence ... on the whole course of society.”

He added, “There is no class of persons who do not exercise the elective franchise, and who do not indirectly contribute to make the laws” except, he admitted, those called “slaves, servants, and paupers in the receipt of relief from the townships.”

A generation later, America sought to right those wrongs. Some still say the wrong wrongs were righted or not righted at all. Former United States attorney Joseph diGenova says we need a second civil war to finish the job.

“The suggestion that there’s ever going to be civil discourse in this country for the foreseeable future in this country” he said on a radio show, “is over. It’s not going to be. It’s going to be total war. And as I say to my friends, I do two things — I vote and I buy guns.”

In an essay on the ways people are connected in real life, the great British psychoanalyst Joan Riviere said we all have a tendency to view each other in “isolation.” It’s a “convenient fiction.”

She said, when one of her patients came to see her in “the analytic room; in two minutes we find that he has brought his world in with him.” She added, “There is no such thing as a single human being, pure and simple, unmixed with other human beings.”

Riviere said, from the day we’re born, we’re all “formed and built up ... out of countless never-ending influences and exchanges between ourselves and others.” Personality appears to be nothing more than an osmotic piece of skin because “other persons are in fact ... parts of ourselves … . We are members one of another.”

A few days ago, as reports of the spread of the coronavirus came in, the President of the United States took $37 million from the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program — a safety net to help those in need pay their heating bills — to help pay to contain the viral epidemic.

He stole the money because the budget he created had cut funds designed to deal with such medical crises. And the temperature in Sinclair, Maine last night was forecast to drop down to 11. A mockery of the “general equality of conditions.”

In July 1854, the 12th President of the United States reasoned to the nation, “The legitimate object of government, is to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but can not do, at all, or can not, so well do, for themselves — in their separate, and individual capacities.”

Abraham Lincoln was speaking the American tongue long before Riviere discovered that her patients spoke similarly. The president was saying that Americans are “formed and built up since the day of our birth out of countless never-ending influences and exchanges between ourselves and others ... We are members one of another.”

The American idiom says, “Crown thy good with brotherhood/From sea to shining sea.”

Location:

Dedicated to Janet Malcolm

When I was in my late 10s and early teens growing up on Staten Island, playing competitive baseball meant you were on a parish team. Every parish had one. There was a citywide league, I think run by the Catholic Youth Organization. Little League didn’t reach the Island until 1953.

I played for St. Mary’s of the Assumption in Port Richmond with my brothers and cousins and other kids in the neighborhood. We lived just blocks from each other.

For three years straight, our team won the Staten Island championship which meant the following week we were on our way to Manhattan or the Bronx to play the winner of that borough, in the semi-finals.

One year we played at Fordham’s Coffey Field, the next at Baker Field at Columbia. There were no backstops, it was like the big leagues.

The other day, I thought of one of the games we played there when I saw an article in the paper that said, during the 2017 baseball season, the Houston Astros cheated during its regular-season home games and that’s why the Astros won the World Series.

I thought of our game because the coach of the other team played an insidiously dirty trick on me, the pitcher, as I was looking for the sign from the catcher. It cost us two runs; we lost the game. The story never made the papers; this is the only report.

With respect to the Astros, the public might never have found out what happened if Mike Fiers, a pitcher for the team from 2015 to 2017, hadn’t told reporters Ken Rosenthal and Evan Drellich of “The Athletic” that, during the 2017 season, the Astros had a spyglass set up in the outfield clubhouse.

By using a telephoto zoom, their mole was able to decode the signs the catcher was giving to the pitcher, and wire the information to the dugout where one of the players signaled to the batter what pitch was coming.

If you’ve played baseball beyond tee ball, you know that knowing what pitch is coming increases your chances of getting a hit. Any ethical hitter or pitcher will tell you the same thing.

That is, when the catcher tells the pitcher what pitch to throw, he doesn’t yell out to the mound: Hey, Al, they’re hitting the fastball, go with the curve!

No, from between his legs the catcher flashes a sign with a confusing flurry of fingers. Only he, the pitcher, and their team know the code that was worked out before the game.

The opposing team knows what’s going on; they do the same thing but, when they are in the field, their job is to break the code. Again, when a batter knows what’s coming, he gets more hits, his job security goes up, his bank account explodes. He becomes a star.

Baseball has an unwritten rule that says it’s OK to “steal” signs the other team is using to outsmart you — but only with the naked eye. It’s a game within a game.

But there’s another rule, written as well as understood, that says superhuman telescopic spyglass equipment is verboten. No James Bond X-Ray glasses allowed.

When Major League Baseball read the piece in “The Athletic,” they went bonkers: another scandal! First steroids, now a Joker with a spyglass?

It’s a strange phenomenon, isn’t it, that a team could feel so insecure about its ability to win that it had to borrow strength from an electronic eye to overcome the deficit. In Freudian terms, it’s the son borrowing strength from the father to withstand the hardships of life, the origin of the superego.

Baseball’s commissioner, Rob Manfred, did not hesitate. He sent his hound dog Department of Investigation out to see out who was responsible. They spoke to executives and conducted preliminary interviews with current and former Astros.

In his report, the commissioner named those responsible for the swindle and what punishment was meted out to each. First, the general manager of the Astros was to be banned from the game for a whole year; the same for the Astros’ manager, A. J. Hinch.

And the Astros’ assistant general manager, Brandon Taubman — who vehemently denied involvement in the scheme — was told that, if he even smelled a baseball for a year, he’d be banned for life.

If you think those penalties harsh, consider that the next day Astros owner, Jim Crane, fired Hinch and his general manager on the spot.

And the ball kept rolling. Alex Cora, the bench coach for the 2017 Astros, and subsequently the manager of the Red Sox — Boston’s ownership fired him on the spot as well. The commissioner’s report said Cora was a ringleader, that he “arranged for a video room technician to install a monitor displaying the center field camera feed immediately outside of the Astros’ dugout.”

Then the Mets joined in. On the spot, the Mets fired the team’s newly-hired manager (and supposed savior) Carlos Beltrán who played for the Astros in 2017 and was a known catalyst in the swindle. He was the only player named in the report.

Those who have any baseball memory know what the Astros did the New York Giants did in 1951 when they won the pennant with Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ’Round the World.” The Giants had a coach sitting in the team’s center-field clubhouse working the spyglass.

For his Jan. 31, 2001 article in “The Wall Street Journal,” “Was the ’51 Giants Comeback a Miracle, Or Did They Simply Steal the Pennant?,” reporter Joshua Harris Prager interviewed Al Gettel, who pitched for the Giants that year. At 83, Gettel said, “Every hitter knew what was coming ... Made a big difference.” Thomson, interviewed as well, spoke like a politician. He did not want to tarnish one of baseball’s golden moments.

With respect to what should happen to the players involved in the scandal, the commissioner caved, “I am not in a position based on the investigative record to determine with any degree of certainty every player who should be held accountable, or their relative degree of culpability.”

But you have the power, Mr. Commissioner, to set up Truth and Reconciliation-like hearings and ask each player on the 2017 Astros: Where did you learn to cheat? Did your parents teach you or did you learn that later in life? When did you become an entrepreneurial brand ready to sacrifice dignity for a diamond ring?

By avoiding the healing narrative that emerges from a truth commission, Major League Baseball is avoiding the structural problem at hand and cheating every Little Leaguer of what he needs to know about to how avoid the lure of larceny.

Do Little Leaguers think that golfing great Bobby Jones was a square for calling a one-shot penalty on himself in the 1925 U. S. Open when he said his ball moved as he set up for the shot. The lost stroke cost him the most prestigious golf tournament in America.

When people lauded Jones for his honesty he said, “You might as well praise me for not robbing banks.”

Charles Van Doren — the Columbia prof who cheated his way to a big-money win on the popular TV game show “Twenty-One” in the mid-fifties — died last April; the headline of his obituary in “The New York Times” read “Charles Van Doren, a Quiz Show Whiz Who Wasn’t.”

My sense is that, when every man who played on the Astros 2017 team dies, his obituary will say, “A World Champion Who Wasn’t.”

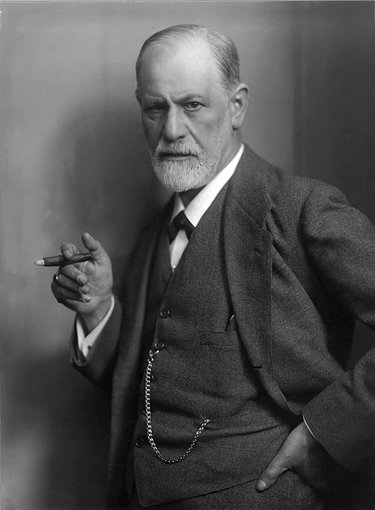

In 1930, the small publishing firm of Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith came out with the first English edition of Sigmund Freud’s “Civilization and Its Discontents.” The book was a kind of Dear John billet-doux to humankind.

Freud, the father of psychoanalysis — the man who sought to understand why human beings find enjoyment in repressing themselves — was wondering whether a civilization, a country, or any social relationship that’s in psychological trouble, can actually rid itself of the aggression that’s killing it.

Three years earlier, when his celebrated “The Future of an Illusion” came out, Freud asked the same question but on a “spiritual” level. He was wondering what kind of psychological succor formal religion can offer a person to get through the day; on a larger scale help that person find meaning in life; and on a still larger scale, help him understand the structural conditions, the social institutions that deny succor to some because of the way they look or think or maybe they’re not a boy or a girl. And the succor is always offered at a price.

I would not recommend “Discontents” to everyone because it contains a lot of mind-testing words from the Freudian lexicon, but the book’s persistent query is: Is it possible to live without aggression toward others (in word and deed)? Why do so many feel compelled to carry a six-gun?

I just finished re-reading “Discontents” to celebrate its 90th birthday this year. The odd thing is, I feel Freud could have written the book about the United States of America today where aggression runs so high that half of the population can’t talk to the other half without waving a stick or carrying a six-gun.

Freud said the questions about discontent and how we might free ourselves from its ravages are “fateful,” that is, they affect the way we live now and well into the future.

He said the “the human species” may never reach a point of “cultural development,” that is, develop the necessary tools, to respond to “the disturbance [that’s affecting our] communal life.”

We’ve “gained control over the forces of nature,” he said, and some people seem ready to use that power to exterminate “one another to the last person.”

I’m sure his tone was affected by the late-1920s Austria where the political left and the political right clashed in the streets. A right-wing paramilitary group, the Heimwehr, decked out in Tyrolean fedoras, could be seen, gestapo-like, parading through Vienna seeking to destroy socialism. A “revolt” took place in July of ’27 where 89 protesters were shot and killed; five policemen died; it is said 600 protestors and as many policemen were hurt.

History tells us Freud was right in using the word “extermination.” In Germany’s September 1930 election — the year “Discontents” came out — the Nazis won 107 seats on the German Reichstag.

On the day parliament was seated, the 107 came dressed in brown military shirts. When the roll-call came to them, each shouted “Present!” punctuated with “Heil Hitler!” Every Jew in Austria could feel the coming Lebensraum.

I’ve been in conversations where the topic turned to people’s likes and dislikes — “I like vanilla ice cream better than chocolate.” “The Yankees are better than the Mets.” “Black and white movies have it over color.” — and, when appropriate, I have asked someone: Do you hate anybody? And if you do, do you do it without guilt?

A reporter recently asked the Speaker of the House of Representatives of the United States Congress whether she was telling the truth when she said she prayed for the president, a man who makes fun of her face and calls her crazy. Does she hate him?

Nancy Pelosi blared: How dare you! Christians do not hate; the basis of our religion is: We deal with disrespecters with dignity. She did not mention Gandhi’s: “Do not fear; he who fears, hates; he who hates, kills.”

If Freud were analyzing the insidious neurosis afflicting the United States today, he’d say its people lack tools, interpersonal tools to get along with each other, and psychological-insight tools to envision a future without aggression — a place where everybody benefits, where everybody’s needs are treated like everybody else’s.

I once was a mediator in the Albany County courts, the small-claims division. When contestants accepted the offer of the judge to go off and reach a mutually-satisfying agreement face-to-face, they and I went to the jury room next door.

I sometimes felt like a marriage counselor for a couple whose righteousness had blinded them to the point they saw each other only as an abstraction.

Minutes before in the courtroom they were saying: Your honor, my opponent is a fool, and the fool would respond: Your honor, talk about fools!

In the mediation room, I quickly had to establish rules that disallowed using words that denied the other’s worth, indicating that mediation works when each person agrees to speak to and listen to the other as an equal.

In almost every case, as happens most times in mediation, things got worked out but I could see that the contestants never really bought the equal-value notion. They just didn’t want to go back to court and have the judge make the decision.

Of course every being can speak and every being can listen in some way but speaking to and listening to another as an equal requires a sharper set of tools, laser-sharp analytical competencies.

In restorative-justice sessions, when someone wishes to apologize to another for the pain they’ve caused, it sounds ridiculous but they have to be taught how to speak, to understand that what they say might cause further harm. The examples are endless.

Three years after “Discontents” came out, the Nazis started burning Freud’s books. Herr Professor told his colleague-friend and later biographer, Ernest Jones, “What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.” Therapeutic irony.

It’s in the last paragraph of “Discontents” where Freud alludes to the possibility that human beings might “easily exterminate one another to the last man.” He said the fear of that causes “a great part of [our] current unrest, [our] dejection, [our] mood of apprehension.”

He said it comes down to whether Eros — Love — will be able to muster the “strength ... to maintain himself alongside of his equally immortal adversary,” Thanatos or Death, which manifests himself in the degrading way we speak to and act toward each other. Ladies and Gentlemen et al, America is not a happy place.

Freud felt compelled to add a final sentence to “Discontents” in the 1931 edition, “Aber wer kann Erfolg und Ausgang voraussehen?” Bob Dylan translated it in his 1967 anthem “All Along the Watchtower”: “There must be some way out of here ... There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief.”

Whether you add an ox, a cow, or three wise men to the first nativity scene in Bethlehem, Jesus, Mary, and Joseph remain the stars of Christmas. For centuries, artists have shown the blissful parents looking down on their child stretched out in a manger — all three wearing a heavenly glow. Guido Reni’s 17th-Century “The Nativity at Night” is a good example.

Because the Roman Catholic Church wished to honor the Christmas trio, they set aside a day in December called The Feast of the Holy Family. It’s (supposed to be) a time for the faithful to reflect on how the “first family” showed them how to be better. But that may be more than the texts allow.

The feast is observed on the Sunday between Christmas and New Year’s and, should these fall on Sunday, the Family moves to the 30th. This year, they’re on the 29th.

To insure that the family continues to receive attention, over the years the Catholic Church has published documents explaining their essentiality. The Benedictine monk Bernard Strasser says in “With Christ Through the Year” that “The primary purpose of the Church in instituting and promoting this feast is to present the Holy Family as the model and Exemplar of all Christian families.”

A lot of people, when asked to describe this family though, conjure up the three in the manger scene and God forbid you interrupt the Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s “Away in the Manger.”

For them, Jesus will always remain a child, thus they never hear what he said about “family” later in life. It results in a spiritual life that lacks the enlightened mind that William James described in 1902 in “The Varieties of Religious Experience.”

I don’t read that much about Jesus but I recently came upon a passage in John Dominic Crossan’s “Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography” (Harper, 1994) where he records what Jesus said about family later in life. Crossan says it’s an “almost savage attack on family values.”

And it started when Jesus was 12, traveling with Mary and Joseph to Jerusalem, like the family did every year, to observe Passover.

All went well until, on the way home, after a day on the road, Mary and Joseph couldn’t find their son among the family and friends who made up the caravan.

Panicked, they bolted back to the city to find the boy, which they finally did, in a temple, sitting among rabbis, listening to what they had to say, but also asking questions, the weight of which made observers turn their heads and say: Who is this kid!

The miffed mother and father went up to the boy — to use a certain parlance — and said: Hey! what’s going on! We’re at our wit’s end! Have you lost your mind! Is this how you treat your family! Is the Holy Family thing off?

And the boy, still racing from the discussion on the moral questions of the day, says — to stay with the parlance — What are YOU doing here! I’m at work! Have you no sense of calling? Why ARE you here!

The two were stunned, the good book says, because they had no idea what the boy was talking about.

I’ve always imagined them saying back — to stay with the parlance — Hey, you! Shut up! Get in the car! You don’t talk to your parents that way! Wait till we get home.

It’s a funny image, isn’t it, the Holy Family of Christmas — advertised by the Roman Catholic Church as teachers of how to be better — themselves in a tizzy: mother and father in the front seat and the kid in the back.

The Gospel of Thomas says the separation language got worse, “Whoever does not hate father and mother,” the older Jesus says, “cannot be followers of me, and whoever does not hate brothers and sisters ... will not be worthy of me.”

Hate? Hate Mary and Joseph? Is this the kid from the manger speaking?

And I must mention that Jesus, by introducing the concept of worth, was entering big-time into the field of economics. Later, as you know, he set a standard for price that was breathtaking.

I’ll add one more from Mark who says that one day Mary shows up at one of her son’s gigs — maybe he was 31. She sends a message, letting Jesus know she’s outside, with his brothers, and maybe he could step out and say hello.

When Jesus hears this, he doesn’t go: Wow, my mother, my brothers are here! Are they OK? Tell them to come in.

No, he says, “Who are my mother and my brothers?” It must have driven the messenger nuts.

The gospel says he then turned to the crowd and said, “Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.”

The messenger must have dropped a second time, hearing a proclamation on what it means to be a follower, a member of the Christian-Christmas family. That is, a loving community is your mother and brothers, a community that allows you to be born again.

Norman Brown in “Love’s Body” (Random House,1966) says that the issue of who’s your mother and brothers is the great political question of the day, of any day, and of every person who wishes to excel spiritually into adulthood.

Look at the annals of psychology, study the mystics, it’s not a Catholic thing or a Christian thing or even a Buddhist thing, but the struggle every person faces with how much they will give to the commonweal, to the outsider, to the good that cements a community of worth.

“Silent night, Holy night” is the quiet that allows a soul to find their community of worth and to create a Christmas in which they become the newborn child in the manger.

William Blake described the firmament as the Mundane shell we are all born in, like a womb; the Christians describe that womb as a living protoplasmic shell whose nutrients — like the yoke of an egg — feed each soul equally from the start and never flag in commitment.

That then is the message of Christmas, that every human being born — whether from a womb, a shell, or the firmament of community — can achieve divinity like Jesus did.

And that’s what the texts allow.

Feliz Navidad a todo el mundo.

Location:

— Photo by Dennis Sullivan

Mike Martin of Voorheesville served in the United States Army for 25 years beginning with a tour of duty in Vietnam from 1967 to 1968. A highly decorated soldier, he sits on his scooter in the village park in Voorheesville in front of a monument dedicated to fellow villagers who died in World War II.

In November 1998, I was scheduled to deliver a paper at the annual meeting of The American Society of Criminology in Washington, D.C. It was part of a session called “The Requirements of Just Community.”

The conference that year ran from the 11th to the 14th, Wednesday to Saturday. Because Veterans Day always falls on the 11th, there’d be lots of people in town.

When I called a hotel to book a room, I was astounded to hear prices way out of whack for what a cloud-ridden November D.C. deserved — I did not know it was Veterans Day.

I asked the lady on the phone if there were discounts, like being a member of AAA. Whatever I said — I do not remember — the price went down 15 bucks. I asked another question and the price dropped again.

Then I asked the associate if that was the best price the hotel offered. She said, well, we do have something and quoted half the original price. I was puzzled; she said it was a “Bounce Back Special.”

Bounce Back? She said, you know, you’re out and about on the National Mall all day, you come back to your room, freshen up and bounce back! Ready to go again.

I booked a room and then asked why the original price was so out of whack for Washington that time of year. She said it was because of Veterans Day on the 11th; there’d be lots of people in town. Supply-Demand.

I said: You mean to tell me that for all the veterans who come to your city missing arms and legs — some still carrying shrapnel in their backs — come maybe to touch the name of a friend on a stone wall — and that for parents who lost a kid in war and still couldn’t shake the grief, for those people, you jacked up the price?

There was a second of silence and then the clerk sheepishly said: I never looked at it that way before.

I tell this story whenever I can but still do not know who the MBA exec was, or who his hired-hand brand consultant was, who gave the green light to the worker bees to jack up rates on those suffering from war. Is that what “Demand” demanded?

Who said the dividends of rich investors should take precedence over the needs of a community striving to keep its consciousness alive by honoring its dead? Who said dividends take precedence over people walking around with one leg because the other was shot off by an enemy of the country?

I’m not a big fan of war but I’ve often wondered about the guy who carries a gun in a far-off land, sent there by supposedly honest officials, to prevent the electorate at Starbucks from having a plane crash into the whipped cream of their lattè.

Jacking up prices and empathy are enemies; capitalism knows empathy doesn’t pay.

I have not known that many people who fought — as opposed to sat at a desk — in war but my Uncle Neil — Cornelius Joseph Sullivan — served in the Navy during World War II and then in Korea, retiring as Commander Sullivan.

He looked beautiful in the full-dress whites of the United States Navy, a specimen athlete from childhood. He’s buried in Arlington National. My brother Jimmy went to see him; he came back saying Neil didn’t say a thing.

The Commander died at Bethesda Naval from multiple sclerosis. I don’t know a lot about medicine but I’ve always wondered if the thing that brought him down wasn’t the South Pacific. I know Ezio Pinza wasn’t singing “Some Enchanted Evening” there.

I’ve long thought that Uncle Neil was a casualty of “the silent residue of war,” those things, factors, biological realities, and psychological nightmares that produce sleepless nights having infiltrated the vet’s DNA long after the war is over.

The silent residue of war is subtle but it does make its way into the protoplasmic-psychological being of its “victims” who never return to “normal.”

Three of my maternal uncles also fought in World War II. I never heard anyone mention PTSD in those days but I never saw any of them dive beneath a table when a firecracker went off on the Fourth of July.

One drank a bit. At the end of a wedding, he’d start crooning old standards in a nasal tenor so that the kids would run around saying: Uncle Franny’s talking French!

Years later, I heard his son say he thought his father was an alcoholic. I was surprised, not about the alcohol but whether Uncle Franny saw things no human being should ever see. But I have no data. As I said, the silent residue of war is subtle.

In John Ford’s “Stagecoach,” one of the fated passengers, Doc Boone, is played by the fiery life-affirming (Academy Award-winning) Thomas Mitchell.

He’s cast as a lush and, because of his drinking, gets kicked out of town — and onto the stage — where he continues to drink but, when called upon to save a life, he appears straight up, front and center.

It didn’t strike me at first, but a way into the movie we find out that Boone was in the Civil War — it doesn’t say as a doctor or whether he carried a gun — but after watching the movie many times I’ve come to the conclusion that Doc Boone was a victim of the silent residue of war.

Walt Whitman, our great national lovely poet Walt Whitman, entered that War to serve the wounded and depressed, to be a spiritual-comfort nurse, offering manly affection to young men hurt and dying of loneliness — 17-year olds pining for mother.

At a hospital in Falmouth, Virginia in late December 1862, he looked out back and saw a pile of severed arms and legs. His diary says, “Out doors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart.”

People who knew Walt before and after the war — the photos confirm it — say he came back different. He suffered a stroke on January 23, 1873 that I believe was the silent residue of war come home to collect.

My friend Dan Okada, a teacher of justice at Sacramento State University, was in the jungle of Vietnam from 1969 to 1970, with the First Air Cavalry Division of the United States Army, constantly under enemy fire.

Since his tour of duty, he wakes up every 2:30 a.m. unable to find relief in sleep. His is a case of the silent residue of war.

Then I see my neighbor, Mike Martin, riding up and down our street on a scooter, having served in Vietnam the same time Dan did. He’s had two operations on his neck and five on his back.

He used to jump out of helicopters from 20 feet, weighed down by 40 pounds of gear and massive rounds of large-caliber ammo. With respect to “’Nam,” he can quote Chapter and Verse.

Looking at his scrunched-up spine, a doctor once asked: Were you a paratrooper? Mike said no and went shopping for the scooter.

To Mike, to Dan, and to all vets similarly situated, I’d like to say: America has not forgotten you. Happy Veterans Day.

I won’t say Thank You for Your Service — some say that’s required — because I have no idea what your war was like, but it makes me crazy to think about those hotel execs who decided to raise the rates on you and your family, looking for a decent place to sleep, some of you rolling into the hotel lobby on a scooter.

Location:

In a dozen different ways I heard people say, after Hurricane Dorian visited death upon the Bahamas, “I can’t imagine what that’s like.”

Of course I, too, was deeply concerned about the devastated souls there, but my thoughts turned to the imagination. Did those people mean that the suffering they saw was so great that their imagination couldn’t take it all in? Were they saying the imagination had limits?

Sometimes when people say they can’t imagine something, they are speaking figuratively but I think what folks were saying about the Bahamas is that they lacked the means to project themselves into the shoes of another.

Again, were they saying the imagination has a ceiling? What are its powers? And what is its purpose in life?

Google “imagination” on Wikipedia and you’ll find a dozen reference works that expound on imagination from a variety of angles — cognitive, poetic, psychological, economic, and political — but that list might be my gloss on the text.

If I had to define “imagination” this very moment, I’d say the mind has an ability to make images, or to combine images that previously appeared and were lying dormant until called upon. Like soldiers in the reserves.

But there are times when images crop up on their own and parade themselves before the mind’s eye — the oculus mentis as the Roman writer Cicero called it. A man can be sitting under the shade of a tree taking in the summer breeze and all of a sudden images of his grandfather appear and start running across his mind like the frames of a movie.

When I taught school years ago, I used to ask students where the imagination resides and they struggled to come up with an answer; they had a hard time placing consciousness too. The question was: Does our awareness of our self in relation to that self, and in relation to other selves, have a locality?

Whatever your answer is, we need to keep in mind that the imagination is a tool of consciousness put into play when we feel a need for a new conceptual world view — to remedy something that’s missing from our lives. The imagination is the daughter of scarcity.

That is, the imagination arose, developed, and continues to exist, because homo sapiens needed a tool to invent, reinvent, capture, project, introject, images to help people meet their needs. In this sense, the imagination is related to dream. When John Lennon chanted his peroration “Imagine,” he was asking the human community: What is keeping us from treating another’s needs as our own?

Historically, the Roman Catholic Church responded to this question with a “mystical body,” a paradigm that says the imagination is an agent of utopia, an envisioner of a world in which the needs of all are met, structurally. Nobody’s left out, they say, according to the gospel of Jesus.

Such a view is an antidote to the static and ill-will people generate when they minimize or dismiss the needs of others. Some do it with insolence and go nuts when they hear the word “utopia.” They flush it from consciousness like a bug pestering their wits while calling the bug a “nut job.”

But nut-job language is a smoke screen; it reflects a deep deep fear of the depths of one’s soul.

Walt Disney — the Walt of Mickey Mouse — demonstrated his utopia by creating animals, people, worlds, and fantasies and then — across the vast multi-acre venues he built — showcased the lives of those animals and people with life-scripts he wrote for them.

When the maestro launched his famed Fantasyland in the summer of 1955, he told those who gathered there that this was his “world of imagination,” a world where “hopes and dreams” come true.

Sounding like a poet, he spoke of a timeless land of enchantment, a land “of chivalry [where] magic and make-believe are reborn and fairy tales come true.”

But he let the crowd know that this land is accessible only to “the young at heart — to those who believe that, when you wish upon a star, your dreams come true.”

What a sales pitch! Imagine: not living on a star but just wishing on it, and you wind up in the lap of eternity.

Keep in mind that Disney — and utopianists of his ilk — let his imagination take him where it had to go; or maybe he needed to go somewhere and called upon it to bail him out. How else could he meet Snow White, Peter Pan, Pinocchio, and the ever-endearing Thumper?

As a scholar of the human condition, I’ve been long interested in the imagination’s ability to allow a person to project its self (consciousness) into the life-circumstances (consciousness) of another, and feel sympathy for that other. Ethicists say that, when a soul gets good at this, it finally has a moral compass.

A lot of people know the Adam Smith who penned “Wealth of Nations ”— a core capitalist manifesto — but earlier in life Smith showed interest in the imagination’s ability to help one person connect with another through feelings of sympathy, what today we’d call empathy.

In “The Theory of Moral Sentiments,” he said such a process is radically transformative — I see no other way to read the text.

One wonders how the Smith of a nationally-sanctioned-private-wealth-production ideology squares with the Smith of empathy, his version of a mystical body, that there’s only one boat.

Utopia is a world, a country, and local communities where people treat the least as the richest among them. In a somewhat oblique way, that’s what the radical American documents of the 1770s were reaching for.

Some of the 2020 candidates for the presidency of the United States seem to reaching for the same thing. It’s certainly a far cry from a political economy where one person can drive another in the ground and live unimpeded.

Some say the driven-down deserve such treatment because they’re losers, lazy, dumb, and lacking pedigree. Maybe they’re a Mexican working in a cement plant breathing in deadly dust or a dark-skinned fellow wearing a dastaar in the front seat of a cab.

The Walt Disney in me says hogwash to those who deny that human worth is based in need — not age or gender or race or any other demographic accident: but need — and that all quid pro quo economies are non compos mentis.

Never mind $15 an hour; let’s put everyone down for a $100,000 a year (including students), and let’s provide everyone with a modest shelter of choice, and let’s guarantee the means to stay alive (health) without imposing tariffs.

Of course in such a society there’s paperwork, there are conflicting differences, and cheaters of ill repute, and those who’ll pull the wool over the eyes of a child for a measly sawbuck.

But, in the world of Walt Disney, the world of a world he brought into being, at least everyone says: I know how you feel. And lots of them do something about it.

Or is that a dream too hard to imagine?

Location:

Often heralded as a cinematic masterpiece, “The Bicycle Thief,” directed by Vittorio De Sica, opened in the United States in 1949; the original Italian “Ladri di biciclette” opened in Italy the year before. Ladri is plural: thieves. A lot of people in the United States use the singular and, in doing so, miss the point of the film.

The movie portrays the life of a poor unemployed man who gets a job pasting advertising bills on city walls. The only requirement for the job is that he have a bicycle; he does but it’s in hock.

His wife strips the sheets off their bed (her dowry), drags them to the pawn shop, exchanges them for the bike, then sends her man off to bring home the bacon. Marx would call the bike the means of production.

On the first day of the job, things start out well but, when Antonio gets up on a ladder to paste a fancy bill, a man sneaks from behind a car and steals his bike, the means to his family’s dinner.

A good part of the movie is the “victim” (later accompanied by his son) trying to track down the getaway man. Walking around depressed because of ill-luck, he eyes a bike in front of the Stadio Nazionale del PNF, Rome’s famous soccer stadium, unattended.

He quickly tells his son to go home and, once the boy’s out of sight, rushes to the bike and is off riding on somebody else’s supper.

But this time — thus “Ladri” — onlookers see the perpetrator and, mob-like, rush the bike, drag the thief to the ground, and pummel him with justice.

The kid, who missed his train, had come back and witnessed the ignominy being dished out to his father.

But there’s a deus ex machina: The guy who owns the bike appears. In the midst of the crowd he peers down at a frightened child standing beside a dispirited soul, and tells the crowd: No big, let him go — and the thief, the second thief, is freed.

Here’s where the analysts come in: The father had been the victim of a crime, an act of hostility, when his bike was stolen. But when he finds himself in a similar situation, that is, when he sees an unattended bike the way his was, he responds not with feeling for how the other guy might feel when he sees his bike gone, but with retributive hostility.

The thinking is: Somebody got me, I’ll get somebody; anyone who leaves a bike unattended deserves what he gets — though the paperer does not say the same about himself, that he deserved hostility in the first place.

When the mob came, the people in the mob also dished out a deserts-based justice, acting like hostile vigilantes. They behaved the way the wallpaperer did. The situations differ, of course, but both reflect a transgression of personhood.

The twist in the movie is that the second victim of a bicycle theft does not respond with retributive hostility but commands the crowd: Let the guy go. He responds with hospitality. He not only stops the mob from beating on the perpetrator but treats the offender as he might a guest in his home or a beloved family member.

On one level, we do not know what the guy’s thinking is, such that he would respond to hostility with hospitality. And yet he’s countercultural in the sense that he contradicts the prevailing ethic to take an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and enjoy diminishing another.

Which is how the current president of the United States behaves. As he said in a November 2012 tweet, “When someone attacks me, I always attack back ... except 100x more. This has nothing to do with a tirade but rather, a way of life!” An admission of a hostile disposition.

Again, we do not know what the second thief’s thinking is about relative worth and how a harm-done should be responded to. Regardless, the father could not fathom what it takes to be hospitable in the face of hostility, to respond to loss with largesse. But that would be another movie.

De Sica’s movie ends with the father, walking home with his son, his tail between his legs. He begins to cry and the son, seeing a man bereft of dignity, takes his hand and offers hospitality — to a criminal, a criminal who happens to be his father. The child has seen beneath the surface separations that keep us apart to where we’re all connected.

I thought of De Sica’s film last week when a story appeared in the news about a bicycle, a bicycle that wasn’t stolen but given, freely given, given by one person to another without knowing the recipient, without assessing whether the recipient deserved it, the only measure being the measure of need, and nothing was asked for in return. Pure hospitality.

The late famous Algerian-born French deconstructionist philosopher, Jacques Derrida, used to say there is no such a thing as a pure act of hospitality, but does not this case of a bicycle freely-given apply?

The recipient of that bike is now a 29-year old Kurdish woman, Mevan Babakar, who was desperate to find the man who gave it to her when she was 5 years old and living as a refugee outside Zwolle, Netherlands.

She went back to that city after all those years to see if she might find, not a getaway but, a giveaway man. She looked in the face of every old man she saw on the street, ready to sing her psalm of gratitude, but no luck.

When she turned to the Web and told her story to the world, in no time the man was ID’ed, but the kind soul said he wanted no light shined on him. He said it was no big deal, all he was doing was honoring personhood.

The 20th-Century Dutch spiritual writer Henry Nouwen looked into this kind of hospitality, asking how people find the strength to offer hospitality in the face of hostility.

In his beloved “Out of Solitude,” Nouwen says hospitable people “instead of giving advice, solutions, or cures, have chosen rather to share our pain and touch our wounds with a warm and tender hand.” They do not steal your bike.

He says the hospitable “can be silent with us in a moment of despair or confusion ... can stay with us in an hour of grief and bereavement ... can tolerate not knowing, not curing, not healing and face with us the reality of our powerlessness, that is [be] a friend who cares.” They do not respond with ire.

I find Nouwen’s words to be a little too abstract but there have been times, when someone stole my bike, that I turned to them for the hospitality they offer.

Location:

On Oct. 18, 1958, “The Saturday Evening Post” published an article by the late British-American philosopher and novelist Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) called “Drugs That Shape Men’s Minds.”

From the title, readers might have thought they were getting something on the Salk vaccine or some other elixir that changed their lives.

But that was not so. It was Huxley telling the public that in the past several years he had taken — on and off — psychedelic drugs and that the experience had changed his life.

He said he saw into, as I read the text, the core of his being where all the pettiness that keeps human beings at odds with each other is miniaturized to nil.

He spoke in the language of mysticism, the way enlightened souls describe their commitment to the All, God, the Universe, replicating the bliss the first human beings felt when they were born.

Fans of Huxley knew what he was talking about. They had read “Doors of Perception” when it appeared in 1954 and deemed it a classic.

There Huxley described his experience on mescaline, a psychedelic drug derived from varieties of cactus which Native Americans in Mexico had known for thousands of years, often in connection with religious celebrations.

Huxley was a low-key and deliberative man but in “Doors” he said in bold print that the images produced after ingesting mescaline (and since then LSD), had rearranged his mind almost primordially. He took a dose and fell into the lap of God or maybe God had fallen into his.

He said he experienced what the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers were after in third century Egypt when they went into the wilderness to strip themselves of every jot that stood in the way of reaching God (the All, the Universe, Collective Consciousness).

I’m not sure what anybody’s view is on things like psychedelics, the experience of God, eternal life, and living purposefully but, when you hear Huxley talk, you wonder if there are rules for such things.

And I’m not talking about the fact that psychedelics have been criminalized in the United States for decades; what the law says, Huxley asserted, is irrelevant to what he was doing — finding God without harming a flea.

But you might ask: What do the doctors say? We do know that under a doctor’s care the actor Cary Grant took close to 100 doses of LSD, saying it made him the Cary Grant cineastes know and love. He was sharing the bliss.

Sometimes the Xanax crowd, when they hear “psychedelic,” get superciliously huffy: You can’t be serious that a drug can produce God. Or the bliss before the Fall. A pill? A tab? No discipline or rules? Call me an Uber!

It’s not funny. A lot of those who read Huxley’s words in “The Saturday Evening Post” got bent out of shape, some hot under the collar.

One of those had been a fan of Huxley for decades, the famed Trappist monk Thomas Merton; he considered Huxley a guru.

When Merton entered the monastery 17 years before, he adopted a lifestyle that scheduled each monk’s actions down to the hour, day in and day out, not even a break on Christmas. The Trappist horarium was contemplative to the core.

Merton wrote about his experiences and, because he wrote with the soul of a poet, became the most important spiritual writer of the 20th century. Many consider him a mystic.

So when Merton read Huxley’s prose, his id sorta went whacko: WHAT! God in a PILL! Has Huxley gone nuts! I’ve been on the purgative path for decades: There is no shortcut — chemical or otherwise.

Merton had not come upon the piece on his own. The monastery did not subscribe to things of “the world” like the “The Saturday Evening Post.” A woman friend of Merton’s sent it, thinking he should know. (An act of instigation.)

Merton says in the Nov. 18 entry in his journal, “Aldous Huxley’s article on drugs that produce visions and ecstasies has reached me with the protests of various Catholic women (sensible ones). I wrote to him about it yesterday and the article is on the notice board in the Novitiate conference rooms.”

Merton was the monastery novice master and he wanted his neophyte spiritual-seeking charges to see up close the foolishness that some, even exceedingly intelligent souls, can succumb to.

In a Nov. 27 letter to Huxley, Merton told his mentor that he was puzzled by all the drug stuff and that, maybe before he weighed in, he ought to experiment himself.

But then he offered a Thomistic, hair-splitting argument telling Huxley his experiences on mescaline and LSD were “natural” and “aesthetic,” flash-in-the-pan ignitions of enlightenment, not reality. And he’d better watch it; he might become an addict!

Merton said the true experience of God is “mystical” and “supernatural” beyond the power of men’s minds. All Huxley got was a Red Bull shot-in-the-arm blink of eternity.

Huxley wrote back telling Merton he knew what he meant. He said at first his experiences were “aesthetic” but they soon morphed into serious foundation-shaking agents.

The full exchange is priceless to read: two giant minds addressing the proper means to a worry-free heaven on earth.

But keep in mind that long before the mescaline, Huxley had written, in1931, “Brave New World,” a depiction of society where people have consigned their lives to imperialist usurpers. Seventeen years later, Orwell followed with “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” and the world had two great 20th-Century dystopias to ponder.

With respect to people consigning their lives to imperialist usurpers and becoming social automatons, Neil Postman said in his 1985 “Amusing Ourselves to Death” that “Orwell feared ... those who would ban books ... Huxley feared ... there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one.” In other words, why explore a mind that’s dead?

Postman added, “Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism.” Orwell feared that “truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.”

When I read those words, I think of America today, hordes of people taking as their best friend: Hydrocodone, Oxycontin, heroin, morphine, fentanyl, chemicals that delete the mind — let’s not forget Xanax and the hourly vape pen at work — resulting in a loss of purpose in life.

The late sociologist David Matza said in his classic “Delinquency and Drift” (Wiley, 1964) that people who live life without purpose become delinquent actors; purposelessness affects stability, they become drifters.

Which is what the United States is today: a nation of drifters, we’re a nation adrift. Nature abhors this kind of vacuum but fascism loves it, imperialist usurpers grifting the drifter.

Location:

To begin a discussion on the spiritual life in the middle of 2019 is to open up a can, no, a barrel of worms — and not for the reasons people think.

Maybe the great English writer on religion and mysticism, Evelyn Underhill, had it right when she began her short but classic treatise “The Spiritual Life” in 1936 with, “The spiritual life is a dangerously ambiguous term.”

I would never use “dangerous” but there are so many misconceptions about the “spiritual life” that I’m tempted to write a book to straighten them out. “What does a spiritual person look like?” “How do such people live?”

And the misconceptions have little to do with the SBNR (Spiritual But Not Religious) and SBNA (Spiritual But Not Affiliated) movements today, which go back to the 1960s when people (in hordes) began challenging the foundations of “church” and “religion.” Monks and nuns fled their digs like fearful birds.

The Pew Research Center’s 2017 survey on “Religion” found that 27 percent of Americans now put themselves in the spiritual-but-not-religious category (up eight percent from five years earlier).

It’s part of the secular humanism movement going on in the country where believers no longer accept “God” as the only source of moral authority. You can understand why worship is down; it’s no longer seen as a binder.

Underhill and more recent writers on spirituality have also dispelled the notion that the spiritual life has something to do with an inner spirit, some kind of spiritual thing inside us. The problem with cultivating such “interiority” is that devotees too often divorce themselves from social life.

Underhill said, “Most of our difficulties come from trying to deal with the spiritual and practical aspects of our life separately instead of realizing them as parts of one whole.”

It’s also strange that some people still believe that a select few have a spiritual life and others not, and that the spiritualists chose it.

The truth is: There is no choice, there never was; every person who’s ever been born has, or has had, a spiritual life by virtue of their incarnation.

The spiritual life reflects a near-genetic consciousness that emerges from experiencing life as finite, a finity that manifests itself in bodily aches and pains and psychological suffering.

The spiritual person — the person who lives a spiritual life — accepts this fact equanimously, which at its best includes accepting all that comes one’s way: There are no pluses and minuses; no state of being is better than any other; living in and accepting a moment of pain is a joy.

Of course, achieving such a state requires great psychological depth, one that must be cultivated. And it’s hardly a consciousness where the person involved is divorced from the world. On the contrary, the deeper a person enters into the solitude of his being, the more he feels connected to every other self. It’s an axiomatic paradox.

The great American scholar of ancient Greek and Latin — who later became a student of what it takes to be happy — Norman O. Brown, describes living such a unified life as the expression of “love’s body.”

In his 1966 book called “Love’s Body,” he laid out the requirements for achieving this highest level of spiritual-life consciousness. At a minimum, he said, it requires the discipline of a Marine.

I do not recommend Brown’s book for everyone. It can provoke a level of reflective self-analysis that can be (disturbingly) transformative and thus disabling.

But those who meditate on, understand, and accept Brown’s use of metaphor, at some point come to see that the needs of others are equal to their own (which is the basis of identity politics). And the quality of a spiritual life is reflected in how well the person lives out the paradox.

The late insightful philosopher Mary Warnock said the connectedness we’re talking about does not emerge from an overarching deity but from an imagination-based sympathy where one person projects himself into the life of another and says: I am you, you are me.

This is the bedrock of good behavior, the basis of a spiritually-ethical-life lived without a god.

And it must be said that without inhabiting such a consciousness — religiously speaking — a person can go to church a hundred times a week and “om mani padme hum” till satori’s cows come home, and be nowhere close to being spiritual.

Neurotic racists go to church, sexist men believe in an all-powerful God then treat their wives as inferior beings. It’s the lived consciousness of the spirit that counts, repeat: lived consciousness.

And one does not have to be a monk or nun to achieve it, only live with the discipline it requires.

When the Beat poet and Trappist monk Thomas Merton finally reached Asia in the fall of 1968 — he had been enclosed in a monastery since 1941 — he scooted about unbeaten paths in a childlike frenzy asking every “holy” man he saw — in India, Ceylon, and Thailand — what the spiritual life was all about. Can a human being really embody love, show empathy and compassion when others tear him apart, cause him grave psychological harm?

In November, he came upon the mystical lama and poet Chobgye Thicchen who had been a teacher of the 14th Dalai Lama when Tenzin Gyatso was a boy.

The lama told Merton that the Buddhists have a word for living a spiritual life filled with love and compassion; he said it was born of an enlightened mind called “Bodhicitta.”

He clarified that there are three levels of such consciousness.

On the bottom rung, there are those called “kingly.” They are interested in the spiritual path but save themselves first, and then go back for others.

On the second level, the lama said, there’s the “Boatman.” They, too, ferry across the river of salvation but bring others with them.

He said the saints — I’ll call them that — on the highest rung are known as “shepherds.” They see the needs of others as equal to their own but go a step further by treating the needs of others as preceding their own. The Christians say it’s because the other person is seen as Christ.

At this level of consciousness, there is no failure because the devotee attends to each person, one at a time.

The lama also intimated that the Shepherd never seeks credit, never looks for anything in return, accepts no benefits or rewards or any other form of payoff. True believers believe that when people reach this level they become divine, the living embodiment of Love.

And none of this, the Shepherds say, has to do with appearances, with amassing things, with getting into power so as to satisfy one’s self first. These are all defensive psychological fortifications which, paradoxically, wind up imprisoning the bearer.

And every spiritual writer, with any sense of proportion, will add that there is no spiritual life without solitude. Solitude is the crucible in which a person dispels illusions.

But go cold turkey and you’ll go nuts. You’ll soon see the need for the discipline of the Marine but a soldier who, as the embodiment of love, is never called upon, nor ever opts, to kill.