For many years now, when Thanksgiving rolls around, I find myself thinking about gratitude.

“Plagued” might be a better word, in that folks, dead and alive, who have done “good” things for me over the years, enter my consciousness and demand attention.

They come in a parade of sorts and are persistent, but in no way Felliniesque. Perhaps you experience something similar.

I know the paraders are not there bodily — many are dead or live far away — but the result of introjection, my taking on the life of others from another world. I know it derives from a continuing sense of obligation and indebtedness.

That is, I remain emotionally whelmed (not over) by how generous people have been in freeing me of worries and debilitating burdens. One came to pump out my cellar during a hurricane, another jacked up the house to make it even again.

You can understand why I’m attached to these “creatures” in a dependent sort of way. They reflect an emotional connection — even though I’m still not able to define it. It’s related to humility though.

I said the paraders persist; they do not leave until acknowledged. They’re here this very moment; I think they’re behind me writing this.

At Thanksgiving dinner, sometimes the person saying grace touches on gratitude by mentioning someone who did something for the family, but always in passing. Folks at the table nod but want to get on with the meal.

I always want to know what lies at the base of that person’s gratitude, especially the connection between speaker and person mentioned. It would say so much about how people experience gratitude.

And I never heard gratitude mentioned at Thanksgiving dinner that wasn’t received with gratitude. It’s always heartfelt.

Because my parading “friends” show up seeking attention, every year I’m forced to withdraw for a bit to attend to their needs. It’s a retreat of sorts as I spend my time figuring out what I’m feeling. It used to be hit-and-miss; now it’s a calling.

I’m on retreat this very moment. And because of what the practice requires, Thanksgiving time has turned into a kind of New Year’s for me, a time to assess where I’m at and what resolutions I need to make to do things better.

I do not make resolutions exactly but I do examine the foundation stones I walk on and weigh the emotional solidity they afford, especially the gifts of those who’ve come before me.

Solidity is a good word. It sometimes shows in directives telling me how to live a healthier body-mind.

You can see it in my consciousness, in the language I use. Language is telltale, it always says where a person’s at maturity-wise, especially how gratitude fits into his life.

I could give you the name of every person in my parade this year — right down to a librarian who walks an extra mile for me almost daily — but you’d say I sounded like the Academy Awards.

If you read at all, you will have noticed the continuing flow of articles about gratitude in newspapers and magazines and on the Internet.

Whole sections of conferences are dedicated to understanding its transformative power. Scientists come with data on how gratitude metamorphizes.

I know that anyone who lives a mature spiritual life (non-pious-oozing) will tell you how intimately they are involved with gratitude, pointing to where it resides at their core.

The data I’ve collected say gratitude is reflected in a level of consciousness that can only be described as equanimous, a mind-set that allows a person to be at ease in the world — because he has solid foundation stones to stand on.

I know there are those with nothing and especially those whose mind nothing has control of, but they too are faced with issues of gratitude in their daily life; no one is exempt.

Taking the time to talk to the paraders is always a joy; a believer would call it a godsend. It’s like spending an afternoon with nine Carthusian monks at the heart of a fiery furnace.

I mentioned “spiritual life” before. Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu saints say gratitude is essential for living like a god on earth. St. Therese Lisieux said “Prayer is an aspiration of the heart ... a cry of gratitude and love in the midst of trial as well as joy.”

Do you buy that? Is gratitude that central to your life? It’s not something that can be bought or sold.

The neuroscientist Alex Korb, in his recent “The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a Time,” starts talking about how to deal with depression, and unhappiness generally.

Then toward the end he comes up with a startling revelation: Gratitude can reverse psychological (and physical) ill-being by rewiring that part of the brain (the anterior cingulate cortex) that controls our psychological elevator.

Who are you to believe, Therese or Korb?

The answer is both, because both are saying the same thing: There’s a level of consciousness where a person understands the importance of all the gifts given him and is thus transformed into a person of peace. Gratitude makes us stop poking other people’s eyes out.

The first person on my parade this year — and he’s been there for 40 years — is Kevin O’Toole, the builder from New Scotland. His unending intelligence in solving structural, electrical, plumbing, remodeling, and hurricane-effect problems has been a foundation stone for me and my family to walk on in peace.

He’s a portrait painter too.

I could say the same about Rich Frohlich, who ran a garage in Voorheesville for 40 years but Jim Giner and Bill Stone, two members of the Voorheesville Fire Department, keep tugging at my pen.

They’ve been walking in my gratitude parade since August 2011 when Irene flooded us out like a river. There was Jim in the middle of the darkened road, red wand in hand, waving cars by, battered by sideways needles of rain.

Then every few hours Chief Bill Stone appeared on our lawn to check the generator the department had set up, asking if we were alright.

At different times, when I saw Jim in Smitty’s, I’d treat him to a drink at the bar, a tiny gesture to help him (me) dry out from the storm.

This is how my Thanksgiving has begun this year. I wonder if you’re experiencing the same sort of thing.

There’s a subgenre of jokes called “the three wishes,” which you might have heard from time to time.

An example is: Three men are stranded on an island. One day, a bottle washes on shore, a genie comes out and tells the men they are granted three wishes.

Astounded, the first man says: I want to go to Paris. And there he is, sitting at a table at Arpège.

The second man says he wants to go to Hollywood and immediately finds himself on a Scorsese movie set.

The third guy, feeling a bit abandoned, says: My wish is to have the other two back here.

It’s a ha-ha joke in a funny sort of way but there’s a deep side to this and all three-wish jokes that’s never looked at. That is, the jokes are a comedic form of utopian literature, here defined as the imagination envisioning a society in which the needs of all are met.

The genie acts like a supportive community satisfying the expressed wishes of the participants — except that we are led to wonder whether the wish of the last person supersedes or cancels out the already-granted wishes of his island-mates.

You might think this is a question for the political economist but it’s the kind of thing we all think about all the time. Do we think of a society where the needs of all are satisfied without grief, resentment, and dismissive disregard? We can tell by the way we talk to each other.

In the United States today, the utopia issue is far from academic because America is faced with creating a new identity out of the ashes of the old apple-pie American Dream.

The great irony of course is that the vast majority of folk are not able to articulate the kind of society they’d like to live in: a time, a place, the kind of family they’d like, the kind of work they’d like to do. They were never given the competency to do so.

They stay away from speaking utopian thoughts, as well, because they know they’ll be laughed at. When people hear someone talking about a society in which the needs of all are met, they turn into a mocking Greek chorus and start with: stupid, insane, pipe dream! Who’s going to pay for that!

It’s strange but there’s a dimension to the human psyche — more prominent in some eras than others — that represses envisioned alternatives. Not to get too analytical but it is in fact the human community engaging in self-punishment — for failing to make good on its collective dreams in the past. It’s Adam and Eve stuff.

We see it manifested in a lack of trust for each other, in a resentment-filled allocation of goods and services, and ultimately in the adoption of authoritarian social arrangements to keep the growling rabble from getting out of hand.

We see acceptance of this way of life in an increasing number of literary and cinematic dystopias, visions of societies that rely on totalitarian or fascist-like social arrangements for survival.

Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” is a case in point. In the spring of 2017, it appeared in a highly-popular, award-winning television series that’s captured people’s minds.

There’s a society, Gilead, militaristic in nature, where women are owned as property. The fertile among them, the Handmaids, are ritually raped so the leaders can offset society’s dwindling population. The old story of women as sexual pack mules.

The cinematic trilogy “Hunger Games,” which appeared in 2012, is a similarly gruesome dystopia, derived from the novels of Suzanne Collins.

The society of Panem holds an annual survivalist-game where 24 young people head into the wild to stalk and kill each other until the savior-seed of the future emerges.

The 2014 film “Divergent,” a dystopia based in Chicago, also drapes a pall over our mutual aid and cooperation traits so future generations will forget they’re part of human nature.

And the young have taken to these dark visions. Harry Potter was the talk of the town for decades but in 2012 the “Hunger Games” took over. National Public Radio said teens were drawn to them like moths to a flame.

This shift in imaginative literature (and film) did not escape the great science-fiction writer, Ursula LeGuin, who died in January. She saw her imaginative-writer colleagues making a living off creating visions that feed human despair.

When she received the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2014, she said we — America — were headed for “hard times” and, to get through them, we need writers who could project “alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being.”

The emphasis is on “other ways of being.” She said we needed more poets and other visionaries, “the realists of a larger reality,” who present societies in which people solve problems through nonviolent means, who figure out how to distribute goods and services without resentment, a society in which people generally feel good about themselves.

The United States of America today does not feel good about herself.

But, as LeGuin pointed out in her highly-acclaimed anarchist-based “The Dispossessed” (Harper & Row, 1974), even in perfect societies, imperfections arise; there’s always work to do, the struggle to be human never ends.

Ironically, while America was debating the tenets of LeGuin’s anarchist society, Anarres, in 1974 sixty-nine leaders of United States society were being indicted for acts of treason, 49 pleaded guilty to selling out the American Dream. Their president escaped on a helicopter.

Two years after “The Dispossessed” appeared, Marge Piercy’s brilliant “Woman on the Edge of Time” arrived. In Piercy’s utopian society, Mattapoisset, no one would ever think of putting women into subservient roles or making them structurally dependent. In Mattapoisset, mothers, nobody in any family, are to be enslaved for the interest of anyone.

We all know that in any society people cheat and steal and take more than they need, but every “per” — as a person is called in Mattapoisset — is guaranteed care for all their needs for life, constitutionally, because everybody, structurally, is deemed to be of equal worth.

If you’re one of those who laughs at utopian thinking because you’re wedded to dystopian dog-eat-dog modules, consider the sabbatical that everyone in Mattapoisset is guaranteed, as they do in universities now, every seven years.

That is, every seventh year, every per is freed from work and family obligations to regenerate, study, think, refresh, reassess the value and meaning of life, fully supported by the community, and without resentment. It’s part of mental health.

You like that sort of thing? Or has dystopianitis pushed you to the point where all you can offer is derision?

Location:

In the lobby along the south wall of the Original Headquarters Building of the CIA stands a statue of Maj. Gen William “Wild Bill” Donovan.

It’s part of a memorial to the Office of Strategic Services, the first full-service intelligence organization in the United States, the seed of the CIA.

In July 1941, Franklin Delano Roosevelt put Donovan in charge of looking into whatever the agency deemed threatening to the security of the United States. Those who work at the Langley, Virginia complex today see Donovan as not only the first director of the OSS but also the “Father of American Intelligence.” He’s their George Washington.

From the outset — even though pre-Cold War — Donovan was interested in finding a drug, a chemical brew, that would make people blab classified secrets, unknowingly and without resistance.

That is, the drug would break down spies, prisoners of war and the like so they would open their memory banks for inspection. Donovan hoped the truth-prodder would also ferret out double agents inside the agency.

In the spring of 1942, less than a year after the United States entered The War, Donovan brought together several prominent psychiatrists and the director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Harry J. Anslinger, and assigned them the task of finding what they referred to as TD, the “Truth Drug.” Years later, Donovan would say they were open to anything: “We were not afraid to try things that were never done before.”

Thus they began with alcohol, barbiturates, caffeine, peyote, and scopolamine (a drug designed to relieve nausea, vomiting, and dizziness from motion sickness). One section of a 1977 Senate Subcommittee report describes experiments with scopolamine combined with morphine and chloroform.

The combo was supposed to “induce a state of ‘twilight sleep’” as Doctor Robert House had decades before with criminal suspects in Dallas, Texas. Pre-Miranda.

For a variety of reasons — the subcommittee’s report is available online — “Donovan’s Dreamers,” as they were called, quickly turned to marijuana. The agency’s scientific team said they could manufacture a clear, viscous, odorless, colorless version of the new TD on the block. Cannabitic juice could be injected in a person’s food — meat, mashed potatoes, salad — or shot into a cigarette waiting for an unwitting subject to light up and spill the beans of subversion.

But the new experiments with “grass” did not provide the reliable data the agency had hoped for. Some people chilled when dosed, others had “toxic reactions.” A declassified OSS document of Jan. 31, 1946 says marijuana “defies all but the most expert and searching analysis, and for all practical purposes can be considered beyond analysis.” Translated: It was time to move on.

Those interested in the United States government’s early search for a truth-producer can turn to Martin A. Lee and Bruce Schlain’s “Acid Dreams: The complete social history of LSD: the CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond” which first appeared in 1985.

The book is filled with a host of undeniable data. Indeed every statement about the government’s involvement in drug experimentation is backed by a declassified document from the archives of the CIA, FBI, and different branches of the military.

And those documents say the fireworks show really began in earnest when the TD explorers tuned into LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide). In April 1953, three days after the newly-appointed CIA director, Allen Dulles, spoke to fellow alums at Princeton University, the agency launched its MK-ULTRA, a powerhouse complex of mind-control strategies designed to achieve international sovereignty.

Dulles told his Princeton chums “how sinister the battle for men’s minds had become in Soviet hands” and it was up to the CIA to declassify the opposition. Enter LSD.

LSD is an atomic drug. It produces effects so primordial in a person that deep personality changes occur in a single session. Therapists had been using it for years to help patients find their way out of despair-riddled confusion.

During the late-fifties, the movie actor Cary Grant took 100 “trips” under the guidance of a therapist. He talks about his ventures in the documentary “Becoming Cary Grant.”

While Grant was morphing into his better self, Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary was using LSD to effect personality change in criminals housed in Massachusetts prisons. In his autobiography “Flashbacks,” Leary reveals how he came to this work and how it eventually got him fired from Harvard.

Regardless, when the government started using LSD, the Keystone Cops showed up en masse. That is, in order to speak with authority about acid, CIA field agents dosed themselves and started dosing each other during coffee breaks while the dosers took out their notebooks to jot down every exhibited deviation.

As part of Operation Midnight Climax, agent George Hunter White set up safehouses fitted with one-way mirrors where prostitutes on the CIA payroll brought unwitting “subjects” to grapple with the mind-bending realities of LSD while having sex.

To expand its work, the agency awarded more than three-quarters of a million dollars ($7 million today) to psychologists, sociologists, and anthropologists to conduct their own studies on how people behaved when acid destroyed equilibrium.

If you’re familiar with the transmigrations of Timothy Leary you know how things changed after he and his Harvard colleague Richard Alpert turned on, tuned in, and dropped out. And, if you’ve read Huxley’s “Doors of Perception” you know people have deep religious experiences on acid; some say they speak to God.

But, if you were alive in, or studied, the sixties you know that at a certain point a crack-down came. In May 1966, Nevada and California led the charge by forbidding the manufacture, sale, and possession of LSD. No more TD for the masses.

The federal government’s Drug Abuse Control Amendment passed the year before gave the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare the power to designate certain “stimulant, depressant, or hallucinogenic” drugs as controlled substances requiring licensing for sales and distribution.

Of course the saddest part of the story was Harry Anslinger’s continuing demonization of marijuana, which resulted in hosts of citizens doing hard time for possessing a joint or two. Colonel Kurtz summed up Anslinger at the end of “Apocalypse Now”: the horror.

Anslinger called marijuana a, “deadly dreadful poison that racks and tears not only the body, but the very heart and soul of every human being who once became a slave to it in any of its cruel and devastating forms.”

He said using it was, “a short cut to the insane asylum. Smoke marijuana cigarettes for a month and what was once your brain will be nothing but a storehouse of horrid specters.”

And forget concentrates like hash; they make “a murderer who kills for the love of killing out of the mildest mannered man who ever laughed at the idea that any habit could ever get to him.”

Anslinger found support for his insanity when “Reefer Madness” appeared in 1936 and the Marijuana Tax Act was passed a year after. Every piece of governmental lit of the era addressing grass, smoke, Mary Jane, reefer — take your pick — said users were mad men hiding in the bushes waiting to rape and pillage your daughter.

It’s autumn 2018 now and things have changed somewhat. There are now nine states and the District of Columbia where a witting subject can buy a lid of Lemon Kush over the counter like a bottle of chardonnay. And the data collected on the ongoing experiment in Colorado, for example, prove that Anslinger had been enveloped in a mirage of madness.

But, as the great American poet Allen Ginsberg, who took nearly every drug under the sun, used to warn: Every time you take a mind-expanding drug, you’re fooling with your nervous system. And that’s no small matter.

Thus, if an explorer in the land of legalized TD discovers that his metamorphoses do not result in personal growth and sharing in convivial community, it’s time to move on.

Location:

It took 10 years of brutal war for the ancient City of Troy to fall; it took one 44-character tweet for the empire of Roseanne Barr to disappear from television. “The Conners” with Barr as queen, like Troy, is no more.

Barr was expeditiously deleted from the ranks of Burbank because, in a tweet on May 29 she called Valerie Jarrett — an African-American woman who was a senior advisor to Barack Obama — an ape, not the run-of-the-mill kind but one infused with Muslim terrorism.

ABC showed en force. Its entertainment president, Channing Dungey, said Barr’s action was “abhorrent, repugnant and inconsistent with our values” and ejected her, to mix metaphors, from the ballpark.

Hoping to reverse her fortunes, Barr kept tweeting but with what can be described as empty, lopsided apologies. At one point, she pulled out the “devil made me do it” card, blaming her venom on Ambien.

Lickety-split a spokesperson from Ambien said, “While all pharmaceutical treatments have side effects, racism is not a known side effect of any Sanofi medication.”

From the denials and excuses she offered, it was clear Barr had little sense of what kind of transformation must occur before a person can offer a sincere apology — to the person harmed as well as the world at large.

Barr’s remorse was summed up in, “I was so sad that people thought it [the tweet] was racist.” (Exegesis to follow.)

The matter kept gnawing at Barr so she felt compelled to appear on Sean Hannity’s show two months later, July 26, to set the record straight. But pretty much everything she said failed to meet the requirements of a sincere apology.

At one point, she turned to the screen and said — to Jarrett presumably — “I’m sorry that you thought I was racist and that you thought my tweet was racist because it wasn’t ... And I’m sorry for the misunderstanding that caused my ill-worded tweet.”

In a myriad of ways, Barr pressed on like this, assuming defensive after self-protecting defensive posture. She was floundering emotionally and ideologically.

Right after Barr’s appearance on “Hannity,” Eric Deggans, media critic for NPR, commented, “Roseanne Barr has just given a master class on how not to apologize for a massive public flameout.”

I know a lot of people, some close to me, who have a hard time apologizing, even a little bit. When “sorry” leaves their lips, it’s followed with a flood of justifications that become masked attacks themselves.

First of all, in a sincere apology there is no “but.” “But” is a euphemism that hides a person’s real core behind justifications: “Ambien made me do it.”

When an apology is sincere, the penitent’s posture is one of owning the pain and suffering he inflicted on another. He takes back the burden he created.

And this requires finding out how the harmful act affected the “target’s” life — whenever possible through a face-to-face dialogue.

And how one speaks at every stage of the process is critical. Nowhere in an apology should there be heard, “Oh, I made an error,” the kind of thing a person says after he’s said two and two are five.

In his beyond-brilliant HBO situation comedy “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” Larry David returns again and again to the issue of apology. Season 5, Episode 4 is emblematic of his thinking.

A young Japanese American, Yoshi (the son of a World War II Kamikaze pilot “survivor”), believes that David, when ordering chicken teriyaki during dinner, is taunting him with “chicken” when David repeats it several times looking Yoshi in the face with vehemence.

When Yoshi tries to kill himself, Larry’s wife among others believes Larry’s labelling Yoshi a chicken was the “cause.”

When a friend convinces Larry he must apologize, the norm-enforcing taunter calls Yoshi on the phone and says, “I’m sorry if I said anything that might have been inappropriate.”

Here, as in the case of Barr, David is not apologizing for the pain he inflicted but for violating some unwritten code of appropriateness.

He gets in deeper when he adds, “I didn’t mean anything to happen” by which he disavows personal responsibility for his act; it’s as if harms happen somewhere out there at random.

Of course subtly implied is: There would be no issue if you weren’t so sensitive.

But the coup de mal comes when Yoshi thinks he hears Larry eating. “Are you eating something?” he asks. A nonchalant David replies, “I’m eating pistachio nuts.”

Feeling victimized (again), Yoshi responds, “You’re eating pistachio nuts while you’re apologizing to me?” With even deeper hubris David goes, “Yes, so?”

Yoshi then sets a minimum standard for sincerity, “You can’t be sincere apologizing and then snack on pistachio nuts.”

David responds, “I’ve snacked and apologized many times and everyone’s accepted it.” Which translated means: Why can’t you submit to my disrespect like all the other dummies I’ve conned?

David then minimizes Yoshi’s pain further: “What, is that a Japanese thing?” That is, is it some kind of subcultural oddity that does not apply to the rest of us? Without a shred of sincerity in anything he’s said, David has re-victimized Yoshi.

Integrally linked to apology, as we know, is forgiveness. And there’s a whole protocol for determining whether an act of forgiving is sincere.

But it should be pointed out that, because someone has apologized, forgiveness need not follow. There is no “rule” that says a person who’s been apologized to must forgive the person who harmed him.

What is remarkable is that there are occasions when a person who has harmed someone refuses to apologize, but is forgiven by his “victim” nonetheless.

When Pope John Paul II was shot in May 1981, he asked Catholics to pray for his assailant, but more importantly he went to the prison where Mehmet Ali Agca was housed to talk about the situation. He then forgave Mehmet.

Perhaps the classic example of forgiveness offered without a precondition is Jesus on the cross. After being whipped, mocked, and dragged through the city wearing a crown of thorns, he says moments before he dies: I forgive all of you who are responsible for this (my death, my murder).

I forgive you, he adds, because you have no idea what you’re doing. You don’t get the big picture of human value and worth.

Roseanne Barr does not seem to get the picture either, as is the case with the character Larry David. Their ignorance resulted in the re-victimization of those they harmed in the first place.

At no time did Barr choose to meet with Jarrett face-to-face, and David diminished Yoshi by calling him on the phone, sadistically eating.

Justifications are a heavy drug. Beneath them beats a remorseful heart but saving face always seems to send that heart packing.

When I ask people how they talk in apology-forgiveness situations, some respond: Is that some subcultural peace-thing question you’re trying to trick me with?

I persist: Would you mind sharing how you apologize to someone? Are you able to forgive when you’ve been harmed? Do you think “sincere” is what they’ll call you when you die?

Location:

The French existentialist philosopher and playwright John-Paul Sartre’s 1943 play “No Exit” (Huis Clos in French), contains one of the most celebrated lines in literary and philosophical history: “L’enfer, c’est les Autres.” “Hell is other people.”

I’ve heard a lot of people say that sort of thing over the years but Sartre, as an existentialist, meant something more.

The play is a narrative about three people who have been “sentenced” to hell: Garcin, Inez, and Estelle. A man and two women.

When they meet, they start fudging facts about their prior lives especially about the acts that brought them to hell. Also they are puzzled about what their punishment is supposed to be.

That is, there is no fire, no brimstone, no “official torturer” working the sinful crowd. All there is is the three of them locked in a drawing room bedecked with a hodge-podge of period furniture, seemingly for all eternity.

Because they shave the truth, they get short with each other; a negativity arises and their distrust strengthens.

We soon find out that Garcin died by a firing squad for deserting in war; Inez, a postal clerk, was gassed by her lover for seducing a friend’s wife; and the beautiful Estelle had an affair with a man whose love-child she drowned in front of him; he then took his own life.

Sartre says hell does not need Torquemada to satisfy justice. It exists when we present a “twisted, vitiated” self to others and this occurs once we’ve accepted twisted, vitiated values as the basis of our identity.

The vitiating twist begins when a person relies on the judgment of others to establish personal definition and self-worth, the polar opposite of those souls who strike out on their own in search of authenticity. Strike out not in a John Wayne individualism sort of way but in a way that involves self-responsibility and includes concern for the needs of others.

Sartre’s existentialism, therefore, is about choices, about making decisions to free ourselves from the imprisoning “gaze” of others, from being the object of another’s view, from a consciousness that projects an identity for us to assume. Often under pressure.

Inez, the existentialist among the trio, says accepting such an imprisoning mode of self-definition is the hell we endure because “It’s what one does ... that shows the stuff one’s made of.”

Sartre wants his readers to see that a person’s decisions toward freedom determine his essence; it does not work the other way around. The pudding’s proof is in action.

A person’s addiction to false-identity-status is highlighted in the play when the beautiful Estelle discovers there is no mirror in the room. She grows anxious and panicky — Sartre called this state of being “nausea” — because she cannot connect with a reality that will make her feel alive.

Pathetically she pines, “When I can’t see myself in the mirror, I can’t even feel myself, and I begin to wonder if I exist at all.”

This frame of mind Sartre calls “bad faith.” It manifests little or no concern for others. It follows the axiom: An inauthentic person’s values cannot extend beyond the prison that contains him.

I’m sure that someone coming from proverbial Mars who watches the news in America today and listens to political commentators from every side of the political aisle, would conclude that America is a living Sartrean hell, a hell of its own choosing.

And should our Martian look at things with an existentialist’s eye, he would see sectors of folks who agree to be locked in a “base” (of ire’s hue), amount to little more than an object projected from a politician’s consciousness, gaze, and critical assessment — not for the collective’s well-being but for his own.

Under any circumstances, it’s not possible to create an authentic self by mouthing a script; this is more true when the script requires a person to fit into a one-dimensional, homogenized reality.

Donald Trump’s base seems to fit such a description having turned into a postmodern version of Marx’s lumpenproletariat.

You can search Wikipedia for what they say about lumpenproles but today they’re described as stereotypical clowns, the kind you find in an absurdist comedy.

Robert Bussard, now a music librarian at Western Washington University, once examined the lumpenproletariat the way Marx and Engels first described it.

He said in “The ‘dangerous class’ of Marx and Engels: The rise of the idea of the Lumpenproletariat” in 1987 that lumpenproles act out of “ignorant self-interest.” They shoot themselves in the foot and call it progress.

Because they are subject to a version of self-victimization, Bussard says they are “easily bribed by reactionary forces ... to combat” those primed to meet the needs of others.

That is, the lumpenproletariat is a spoiler. It does not “play a positive role in society,” Bussard adds, “Instead, it exploit[s] society for its own ends, and [is] in turn exploited as a tool of destruction and reaction.”

I’m sure you know people like this. They yell, they shout, they think it’s possible to keep things the way they were before the current upheaval began. They’re John Wayne or a comedian playing to the weakest part of the soul.

In movies and on TV these days, hell is projected in a host of dystopian formats, the bastard offspring of George Orwell’s “1984” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.”

In such works — include Marge Piercy and Ursula Le Guin’s among them — every soul from the orchestra seats to the far mezzanine — is panicked for a way out. Like everybody else, they do not like hell and scan the walls for a breach they might squeeze through and breathe life.

All of which points to how difficult change is. It requires re-vision, re-configuring the way the eyes see by reconnecting them to the heart, that is, creating a political economy in which the needs of others count as much as our own.

I ask people all the time about the means they use to escape the unhappiness of their hell — pharmaceutically and otherwise. At first they’re stumped, they stumble over the words. They never thought through what it means to see others as they see themselves.

In the speech he gave in December 1980 upon receiving the Nobel Prize for literature, the Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz said that freeing one’s self from prison requires a special kind of vision, the kind poets have: double-vision.

Milosz said poets see close-up and face-to-face, but they also see from up above, in overview, not sequentially but simultaneously.

Milosz used Selma Lagerlöf’s “Wonderful Adventures of Nils,” to make his point. Like Nils, he said, the poet sees close up but he also “flies above the Earth and looks at it from above.” He sees it “in every detail” but also “beholds under him rivers, lakes, forests, that is, a map, both distant and yet concrete.”

This is not a therapy session so how to get such a vision needs to be discussed. It will take years.

Realizing this explains why so many people are angry today. They do not want to have this discussion, they deny its importance and, in doing so, encase themselves in hell, a base that feeds on despair.

This may be cause for hope because, as Sartre said in his 1943 play “The Flies” (Les Mouches in French), “Life begins on the other side of despair.”

Location:

The great American western “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” is a cinematic paradox. It’s set in the Old West but it’s a movie that reaches our times.

“Valance” is the story of a town coming to grips with a bully who runs roughshod over the civility of its everyday life by using violence to get what he wants.

Lacking self-control, the bully turns the town of Shinbone into a vortex. His name is Liberty Valance or “bad violence man.”

Early on, we see Valance and his few spineless thugs — pawns of the territory’s cattle barons — hold up a stage and, after forcing the passengers out onto the road, strip them of their valuables.

When Valence starts to rip the pendant off the neck of a frightened old lady, the indignant passenger next to her intervenes and for his act of courage is beaten close to death.

The man of courage is Jimmy Stewart, a lawyer by trade who’s headed west with satchels of books to teach the frontier how to settle differences without the use of violence. Stewart is “rule of law man.”

From the outset then, we see the rule of law beaten into submission by bad violence, making us believe that violence will be the way things’ll get done in the territory.

But John Wayne is in the movie, too: a middle-aged, purposely-driven, psychologically-detached, one-dimensional rancher who looks formidably-handsome in his white ten-gallon hat. He has dibs on the lady at the diner, which everybody in town knows.

They, including Valance, also know that the Duke is the toughest man, the fastest gun, in the territory. In a tense standoff between the Duke and bad violence man in the diner where the Duke’s gal works, Valance is forced to beat it out of town, his tail between his legs.

Valance, the Duke says, is “the toughest man south of the Picketwire … next to me.” We can see he’s a man not to fool with. “Out here,” he says, “a man settles his own problems.” The Duke is “good violence man.”

He’s at the other end of the spectrum from Valance but it’s still the spectrum of violence.

And because good violence man beat bad violence man, and bad violence man beat rule of law man, we conclude that good violence can beat the rule of law as well — with a gun if need be.

The movie’s not even halfway through and already we see the rule of law stretched out on the ground with the black boot of violence — good and bad — standing on its neck.

Because his identity is based in the shaky foundation of power, Valance is thin-skinned. When he sees a story on the front page of the “Shinbone Star” critical of his mania, he throws a fit, raging about “fake news.”

He heads to the paper with his thugs and beats Mr. Peabody, the affable, bibulous publisher-editor, into nothingness just like he did with rule of law man.

Valance doesn’t want to be reminded of the weaknesses everyone knows he has. The paper articulates how bullying continues to bring pain and suffering to people’s lives — not the cattle barons Valance works for but the regular, everyday folk who strive to make Shinbone a cordial community.

Fast forward to the end — how we get there is explained in between — and we find the rule of law man forced into a showdown (on the main street of town) with Valance. The choice is clear: the rule of law or bullydom as the prevailing social ethic.

We all know the tenderfoot from the East is no match for a seasoned gunslinger especially when his weapon looks like a broken cap gun. Drawing his gun, bad violence man toys with the rule of law like a cat administering flesh wounds to a mouse.

Tired of the hunt, Valance aims his gun to drill the sockets of the law man’s eyes. Law man raises his piece and Valance falls down dead in the street. There is rejoicing: the rule of law has prevailed over bully-violence, the wicked witch is dead.

Thus the once-mocked agent of law is now revered as the man who brought evil down, who dismissed the use of violence as an ethic of worth. For his bravery, rule of law man is selected to represent the territory in its move toward statehood.

But halfway through the nominating convention — through a strange turn of events — Shinbone’s holy hero is told by good violence man that the law did not bring Valance down but he did, working with a Winchester from the shadows of an alley.

The revelation is disorienting. The rule of law did not bring bad violence down but good violence did. The law did not have the juice to take bad violence down; it took a “good” gun-packing bully disguised in the white hat of justice to do it.

Every day of the week on television, I see public officials, news anchors, political pundits, and people of the most conservative political ilk, call Donald Trump a bully with zero respect for the rule of law. Some say Trump is a gunslinger of sorts.

When I watched “Valance” the other day, Trump came to mind, an hombre who makes fun of the rule of law, who beats down the Mr. Peabodys of the world, and steps on anyone who stands in the way of his selfhood.

When this bully’s wife was most vulnerable after having a baby, he bedded a porn star to satisfy his adolescent libido. He himself says his needs take precedence over those of the collective — the rule of law be damned! In one way or another, he reiterates: I’m the fastest gun in Shinbone, try me.

On my list of the top 25 westerns of all time, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” is Number One. “Shane,” “Red River,” “The Searchers,” “My Darling Clementine,” “The Ox-Bow Incident,” “High Noon,” and “Stagecoach” are not far behind.

In a review of a Harvard Square Theater production of “Valance” in the March 18, 1967 issue of “The Harvard Crimson,” Tim Hunter wrote that the director, John Ford, was “not interested in reality but in [a] subjective viewpoint, not fact but romance and legend.”

But such an assessment is wrong. Ford wants America to see there are times when “the people” are tempted to adopt violence as a way to govern and will mock the rule of law on its way to self-destruction.

When you view “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” you wonder if the rule of law does in fact have the juice to keep violence — good and bad — in check, and whether the United States today, as has happened at other times in history, will let the black boot of violence stand on its neck without uttering a sigh of indignation.

Location:

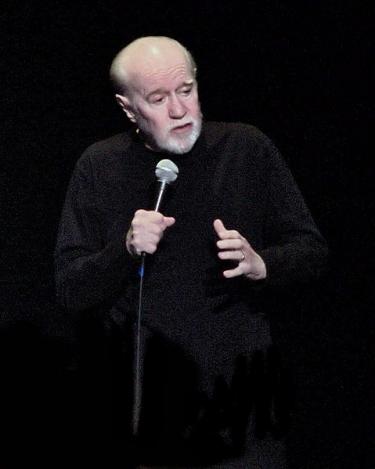

George Carlin is the greatest comedian of all time. Some “best of” lists put Pryor first and Carlin next but others say Carlin is a league all his own.

Jon Stewart may have solved the problem in 1997 when he introduced Carlin during the comic’s 10th HBO special “George Carlin: 40 Years of Comedy” as one of the “holy trinity” of comedy: Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, and George Carlin.

Carlin traced his roots to Bruce and, before Bruce, to Mort Sahl, a lineage of social critics who, through the millennia, called Aristophanes, the “Father of Comedy,” the seed of their comedic work. It was a bloodline that did not suffer Borscht Belt mother-in-law, two-guys-walk-into-a-bar, and lost-airline-luggage jokes.

While Carlin started out with a suit-and-tie Vegas act, when the Sixties rolled around, a beard appeared and his hair fell to his shoulders. He painted iconic characters like Al Sleet, the “Hippy Dippy Weatherman.” Fans recall with delight Al’s: “Tonight’s forecast: Dark. Continued dark tonight, turning to partly light in the morning.”

It seems from the beginning Carlin was piqued by people’s disabuse of language through mystifications, masked contradictions, and linguistic absurdities. While he could garner a laugh from his oxymoronic “jumbo shrimp” and “military intelligence” bits, his true interest lay in sustaining an attack on those who devalued the gift of language by using it to obfuscate reality.

In a classic bit on euphemisms he said: “I don’t like words that hide the truth. I don’t like words that conceal reality. I don’t like euphemisms, or euphemistic language. And American English is loaded with euphemisms. ’Cause Americans have a lot of trouble dealing with reality. Americans have trouble facing the truth, so they invent the kind of a soft language to protect themselves from it, and it gets worse with every generation.”

Those familiar with comedy know Carlin was arrested at Summerfest in Milwaukee in July 1972 for saying the “Seven Words you Can Never Say on Television.”

It was a bit he introduced on his best-selling album “Class Clown” two months earlier. “There are 400,000 words in the English language,” he began, “but only seven of them that you can’t say on television. What a ratio that is! 399,993 to 7. They must really be bad.”

You can see why Carlin remained an “outside dog,” as Mort Sahl would say. In the preface to his 2004 “When Will Jesus Bring the Chops?” Carlin revealed: “I’m an outsider by choice, but not truly. It’s the unpleasantness of the system that keeps me out. I’d rather be in, in a good system. That’s where my discontent comes from: being forced to choose to stay outside.”

In each of his 14 HBO specials, the first aired in ’77, he hammered away minute by minute at the shaky myths the human community creates and submits to thereby limiting its chances for achieving well-being. He spoke about the “American Okie Doke” with its pithy equivocations: “all men are equal;” “justice is blind;” “the press is free;” “your vote counts;” “the police are on your side;” “the good guys win.”

He also went after the duplicities of religion, spoliative parenting, the hubris of prayer, demeaning education, illness-producing health, the glorification of the military, and a pandering self-help movement. He made his fans laugh but he pounded out his points with such vehemence that anyone who went to see him live had to take a day or two off to let the mental dust settle.

In many respects, Carlin was a Socratic prizefighter faulting the Athens of his day, the hoi polloi, for submitting to the demands of the powerful and for settling for a robopathic existence energized by consuming the packaged goods the market sells as indispensable for survival. He blurted that the gods of nature were on their way to strip this planet of sentience.

One group he especially liked to buzz were helicopter parents, the familial wardens who hover over their kids to insure they grow up to be disciplinized, docilized consumers of packaged realities.

Thus for kids he said, “The simple act of playing has been taken away ... and put on mommy’s schedule in the form of ‘play dates.’ Something that should be spontaneous and free is now being rigidly planned. When does a kid ever get to sit in the yard with a stick anymore?” And maybe dig a hole with it. He said that.

The stick is a metaphor for the imagination of course, kids not being given time to think and muse, and sometimes peer at the sky on a summer day to wonder how it all came to be.

Carlin well understood his professional development. Playing off a paradigm of Arthur Koestler on creativity, he acknowledged that he started out as a jester, comedy’s bottom-rung.

But, he added, when he began to follow ideas to their logical conclusion, he turned into a jester-philosopher; his routines changed. He said after that, because of his love for language, he reached the pinnacle of comedic art: the philosopher-poet.

The unending flow of his HBO specials forced the philosopher-poet to become a writer; he said they made him a writer-performer. And, if someone failed to acknowledge the writing as central, he’d set the record straight straightaway.

And it became clear that, the more America sold out her dream of equality and justice, the darker Carlin’s comedy got, very dark, in fact fading to black in his final HBO Special “It’s Bad for Ya.” He said the human race could blow itself up for all he cared; the planet would survive.

Over time, Carlin’s fancy for drugs forced him (in 2004) to go somewhere to get unhooked. On the road nearly every week of his adult life, he struggled with being a good husband and father. In “Conversations with Carlin: An In-Depth Discussion with George Carlin about Life, Sex, Death, Drugs, Comedy, Words, and so much more”, published in 2013, Larry Getlen presents a man who speaks about every aspect of his life with disarming honesty.

Carlin made million-seller comedy albums, he hosted the first “Saturday Night Live,” he wrote funny books, and in 2008 was posthumously awarded the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, I believe for being a great American.

Next month, that great American will be dead 10 years; I hope he’s doing well. Let us know if you run into him. The sad thing is: No one’s picked up the mantle of philosopher-poet.

The Australian-born but Americanized comic Jim Jefferies comes closest. Popular wits like Louis C. K., Amy Schumer, and Kevin Hart and a host of similars remain as distant from Carlin’s soul as Myron Cohen was 70 years ago. Even Chris Rock misses the boat.

As Carlin poured salt on America’s wounds he was the first to admit “Scratch any cynic and you will find a disappointed idealist.” And if he had had, like the comic legend Bob Hope, a theme song, it would have been “America the Beautiful” and Carlin would have pointed to the line “God mend thine every flaw” and say that was not God’s job but his.

Location:

I don’t know what your history classes were like in school but, when you studied the Civil War, were you taught the South had the “bad guys?”

It’s more than 150 years since the war and some southerners still say the North has the bad guys. Last summer, a band of Confederate-based, Nazi-leaning demonstrators in Charlottesville, Virginia waged a pitched battle on that city’s streets against citizens demonstrating for peace. One ill-witted Confederate cut down a living flower with the bumper of his car.

And some southerners still say the South was inches away from winning the first time. Terry L. Jones in a March 2015 article in The New York Times, “Could the South Have Won the War?,” quotes sources saying that, if Lee had tweaked his military strategies here and there, we’d all be singing Dixie.

In a comedy bit on the last week of the Letterman Show in 2015, Norm MacDonald opined that, when Germany went to war with “the world,” it was close. With a few turns in Wehrmacht fortune, we’d be goose-steppers.

During an interview with Elliot Mintz in 2015, as part of a celebration marking his 90th birthday, the social satirist Mort Sahl — the first modern stand-up in history — expressed concern about how the current civil war in America is going.

With a tone of pained uncertainty, he non-rhetorically asked the interviewer: Don’t the good guys always win? Isn’t that how things turn out in history? It was a latent fear of fascism’s growing claim on America.

Early in his career, Democrats accused Sahl of being a conservative, Republicans said he was a Commie. In “Last Man Standing: Mort Sahl and the Birth of Modern Comedy,” the wonderfully-written new biography of the comic, author James Curtis quotes Sahl as saying both camps were wrong; he said: I’m a radical.

Radical in the sense that he kept his satirical light shining on the powerful as they stepped on the dignity and well-being of people whose needs they dismissed as unworthy of attention.

Sahl hoped that, because a person has a particular race, color, creed, gender, or some other defining attribute, he would not be excluded from being treated as fully human. Consider the two black men arrested at a Starbucks in the City of Brotherly Love two weeks ago as they waited for a friend inside the café.

The satirist also used a word seemingly out of character for him; he said Americans have lost their commitment to “nobility.” In saying so, he sounded like the great 20th-Century poet Wallace Stevens who in his classic essay, “The Noble Rider,” addressed the nobility of the poet, laying out the requirements for being noble.

Stevens says the poet fulfills that function when he offers up his imagination to the community so the community can find the courage to delve into its unconscious ways and examine the justifications that induce people to become “bad guys.”

Those who persevere in the process develop an acute sense of human dignity, dignity as a political-economic variable that equates with a person’s worth.

Stevens said withstanding the abrasive assaults of bad guys requires “a mind of winter.” That’s what his beloved poem “The Snow Man” is about, standing up to the incursions of power, the deadly winter we create for ourselves.

I’ve mentioned the ongoing civil war in this country before. Some people seem unable to grasp its cultural context; a few say it’s a touch of conspiracy.

A person picks up a gun and shoots another dead. We see the death, we see the gun, we see the war. But today people obliterate each other ideologically, as when someone says to another: You’re dead, you’re of no account, your point of view is nothing, you’re a bad guy — and there’s nothing you can do for redemption.

The justification for this military incursion comes from a deserts-based view of reality. You hear it all the time: Hey, you don’t deserve this, you’re a Mexican! You’re nobody! Hey, you don’t deserve this, you’re a woman, you’re not equal! You’re a non-deserver too.

Civil war always has to do with deserts, over who deserves what according to pre-assigned value. If those who assert “conspiracy” wish to address value, they can deconstruct sexism, racism, ageism, classicism, cultural chic-ism, and all the efforts of the powerful to enforce modern-day versions of — shall we say: Aryan supremacy?

As our civil war continues, people of different ilk blame Donald Trump for pouring kerosene on the fire. But it’s not “Trump” because, if he had not come along, somebody else would have, so disconsolate is the Confederacy to find a secessionist standard-bearer.

Trump is a mirror for America to look at herself to determine how long she will allow her citizens to flail away at each other with unbridled id; Trump’s the clarion call for a secession-nation that devalues American commonweal. The lie promulgated by such an assault is that social institutions do not require benevolence for sustainability.

You can see why terms like “conservative” and “liberal” no longer have meaning. They’re like worn-out prize fighters banging at each other’s head to seize the title of: Assigner of Value and Worth.

And while the rights of all — including clouds and rivers — always require protection, the political economic map of a sustainable American future is rooted in needs, in communities across the country finding ways to meet the needs of all their citizens.

The nagging big-elephant-question in our national room then is: Are you a good guy or are you a bad guy? How do you know?

Outside the political boundaries of left and right there is indeed a measure to determine if you’re good: To what extent have you dedicated yourself to relieving the pain and suffering of others by tending to their needs? And do you support programs designed to do so?

Good guys are like living-hospice-morphine-drips, first listening to what people say their needs are, and then taking steps to meet them. In his 1559 drawing “Caritas,” Pieter Bruegel portrays neighbors meeting the needs of each other with a reflective tenderness. Is that not what their faces show?

If a person has one meal today and you come along with two, that person has three; it’s measurable. If a person is living in squalid conditions and you provide quarters that support the dignity of the person so he can sit quietly and ponder with gratitude the life he was given, it’s measurable.

Call yourself what you will — left, right, down, up in the air — the new American dream calls for needs-meeters, relievers of the pain and suffering of fellow Americans without charging for offered aid.

The decision to “form a more perfect union” and to “secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity,” as the Preamble to our Constitution says, is formed in the national unconscious. How a person handles the darkness there determines whether he becomes a good guy or a bad guy.

Location:

If you surf the Internet for “letter-writing,” you will find a scad of links bemoaning the disappearance of the “art.” That’s what they say, they say letter-writing is an art, a competency that’s gone by the boards.

When the American poet, Hart Crane, stumbled on the letters of his mother’s mother, Elizabeth, in the attic one rainy evening, as he tells us in “My Grandmother’s Love Letters” he saw packets “That have been pressed so long/ Into the corner of the roof/That they are brown and soft/And liable to melt as snow/.”

As he sat in the dim-lit space caressing the hand-writ delicacies, he realized that, “Over the greatness of such space/Steps must be gentle./ As is the case with any treasured love.”

My late Uncle Neal — who fought in World War II and Korea, retiring as a Commander in the United States Navy — married a Florida woman, Eleanor Perkins, in June 1944. She had two children by a previous marriage whom Neal took on as his own.

I searched and searched and found the children, one of whom was still alive, in his eighties, Frederick Perkins. He didn’t take my call at first; he said that he thought I was the Conservative Party looking for money. I told him who I was and how I got there.

He was a first cousin, at least until Neal and Eleanor divorced. My uncle was a handsome rugged athlete with considerable gravitas but never seemed to have success with women.

As we talked by phone, Frederick said Neal treated him like a son. He did not mention his biological father; he intimated Neal was his dad.

Frederick said Neal wrote to him after he was drafted in the Army. He said he still had the letters and, after a minute or two, asked if I would like them. I was dumbfounded: the revelations of an uncle I hardly ever met or talked to.

In a few days, a packet came with 10 handwritten letters in their original envelopes. Neal was always asking “Freddie” how he was doing, what his plans were, and sometimes offered advice. As I perused my treasure, I knew how Crane felt.

But, as I said, the competency for sharing who you are by letter has all but disappeared; the “art” is a has-been. If I asked how many letters you wrote this month to a friend or someone in the family, what would you say?

Nearly a century ago, Emily Post offered in her 1922 edition of “Etiquette In Society, In Business, In Politics and At Home”: “The art of general letter-writing in the present day is shrinking until the letter threatens to become a telegram, a telephone message, a post-card.” And now there’s texting, Instagram, and all the other modes of surface-revelation.

In a February 2016 article in Odyssey, “Why Don’t We Hand-Write Letters Anymore?,” Ashtyn Leighann said: It’s because we’re lazy. She also mentioned the price of stamps, but where can you get a letter delivered 3,000 miles away for half a buck? Her reasons are facile.

I’m not trying to set up a straw woman here to knock it down, I’m saying I have not seen anything that hits the “why nail” on the head. The answer is: We no longer write letters because letter-writing is a contemplative activity and we — Americans are not alone in this — have rejected contemplation as an integral part of our lives. A jaded critic would say we despise it.

When you listen to the voice that speaks in a handwritten letter — not about the weather — you hear an entirely different voice from what you hear on the phone. The letter-voice comes from a whole other place of being than where the chief-operating-officer-self does business. The letter-voice is open and vulnerable as the soul reveals itself freely.

And the contemplative dimension that allows the soul to write will not return until we embrace (or re-embrace) solitude; solitude provides a safe space where the heart can feel and say things as they are.

When we think of the voice we listen to a letter with, we know it comes from a deeper place than where we listen to a TV show.

I go by the old Irish saying, “If a thing is meant for you, it won’t pass you by,” so I am not about to tell anyone they ought to start writing letters by hand, much less with a fountain pen, though writing by hand is well suited to the tempo of the thoughtful tongue.

Stephen King tells us he wrote his 900-page novel “Dreamcatcher” with a Waterman fountain pen; elated he said, “To write the first draft of such a long book by hand put me in touch with the language as I haven’t been in years ... One rarely finds such opportunities in the twenty-first century, and they are to be savored.”

I write letters. I write them by hand. I write extended notes on 100-pound Strathmore Bristol, the 300 Series, cut in 5-by-11-inch strips. I use a fountain pen. I have one in each room where I write to those I care for.

I find the ballpoint pen an insult. Its leaky nose pales in comparison to the sensuous movement of a nib skating across a sheet of paper made for art. As the ink soaks in, I can hear the sigh of relief: está bien.

Younger people’s handwriting is so atrocious these days because they do not know what it’s like to speak by hand. If you think of what you say as art, you will create beauty on the page and, as John Keats said, “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.”

I get notes sometimes penned in chicken-scratch. I always feel the writer wanted to be somewhere else. I’m not saying someone need adopt Spencerian script or give a nod to Palmer, only that how we put our thoughts on paper, is a reflection of who we are, a measure of our discipline.

Read the letters of Emily Dickinson to her sister, Lavinia, or the letters of Thomas Merton, to the great (still-living) Nicaraguan poet, Ernesto Cardenal — one of his novices at Gethsemani in the 1950s — and you will see an openness that is disarming. The artful letter disarms.

Will America ever regain its lost contemplative spirit and feel safe enough to say who we are and what we think in handwritten letters? If such letters are in fact disarming, might they ease our current civil(ity) war?

I’ll continue to write mine. I derive great satisfaction from it. But then you’ll have to ask those who get them, what they think of a soul speaking from the solitude of his being.

Location:

I have often wondered what it’d be like to be the grandson of George Wallace, the former four-term governor of Alabama.

In particular, I have in mind when he stood in the doorway of Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963, blocking Vivian Malone and James Hood, two black students from getting to class.

Wallace saw it as a way to live up to his inaugural vow: “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” six words that still sit atop the most-ill-famed shibboleths of the 20th Century.

Wallace said those words but they were writ by fellow Alabaman, Asa Earl Carter, a hopped-up Klansman whom the governor hired to write his words. Wallace tapped Carter because Carter knew the kind of violence the governor was attracted to.

The regular Klan had not been good enough for Carter; in the mid-’50s, he started a Nazi-style-shirt offshoot of the group called the “Original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy.” He knew it’d work, he said, because “the mountain people — the real redneck — is our strength.”

Much of that “strength” used to read the Confederacy’s periodical, “The Southerner,” which targeted the weak and the outcast, the sheep who needed a shepherd not a sadist of ridicule and violence. Some of the confederates were ready to take action.

On Labor Day, 1962, six of them — Bart Floyd, Joseph Pritchett, James N. Griffin, William Miller, Jesse Mabry, and Grover McCollough — got lathered up to the point where they needed to “grab a negro,” “grab a negro and scare hell out of him.” That’s what the court record detailing the event says they said.

Newspaper accounts say the “Dirty Six” were riding down Huffman-Tarrant City Road when they saw a middle-aged black man walking with his girlfriend; his name was Judge Edward Aaron. He was a World War II veteran who some said was a bit “slow.” Maybe because of the war.

The mob grabbed Aaron, dragged him into the back of a car, and drove him to a cinder-block hole called “The Slaughter House.” They pummeled him with mockery and then hit him over the head with a tire iron, knocking him senseless.

Then one of the boys took out a package of razor blades, which they’d stopped off to get on the way, and proceeded to cut Judge Edward Aaron’s testicles off. As Aaron lay soaking in his blood, one of his fellow Alabamians poured turpentine of his bleeding self, I’m sure for further pain.

How do some people derive sadistic pleasure from hearing a fellow human-being squeal like a smitten pig — that they’re causing! The six dragged the bloody mess back into the car and, after going a bit, dumped him into a creek bed, leaving him for dead.

But Aaron lived and, when the facts were sorted out, the police took the six into custody. Concerned about their hides, two of the six turned state’s evidence; the other four got 20 years apiece.

But when my imagined “grandfather,” George, became governor, he shifted agency personnel around and the four were set free. Apparently severing the testicles of a black man for personal sadistic pleasure did not deserve a place in the Alabama penal code.

When I think of Wallace as a grandfather I’m overwhelmed with the thought of the work I’d have to do to disengage from my family’s social DNA, a gene that supports purging groups of human beings from the Earth like Nazi soldiers.

What a lot to chew on for a kid who’d like to live a life of justice, who not only does not wish to harm others but supports meeting the needs of every being despite race and creed.

Engaging with one’s social DNA is not a game. People are faced with realities that sometimes breed strange proportions.

When the American actor and filmmaker Ben Affleck found out his great-great-great-grandfather, Benjamin Cole, the sheriff of Chatham County, Georgia, was a slave-owner, he refused to go on PBS’s “Finding Your Roots” because that fact would be revealed to the public.

In another segment of the show, actor Ted Danson, wondering what he would find out, wistfully whined: Oh, please don’t tell me my ancestors were poor! Danson is wealthy but he knew that, if he found out “poor” was in his genes, he’d have to spend time examining the complex.

Social DNA flows from generation to generation like a tiny rivulet and pervades all who follow in the family, leaving each person to figure out the ways those genes drive him or her to ill or good. It’s not a minor matter.

Even those blessed with saints in the family are not exempt. The American writer Kate Hennessy, whose grandmother was Dorothy Day of the Catholic Worker Movement, introduces us to how she faced her derivation from a “saint” in a disarmingly personal way.

In her well-received 2017 “Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty; An Intimate Portrait of my Grandmother,” Hennessy tells us how she worked through the gene of having one of the most revered Catholics of the 20th Century as a grandmother.

Day’s case, as you may know, was put before the Vatican by Cardinal Dolan, the Archbishop of New York, as someone who lived a life of “heroic virtue” and should be declared a saint.

Day had set up Catholic Worker communities around the country — and now the world — that offered hospitality to those in need of food, shelter, and clothing; many of today’s 200 communities in the United States have cots and hot soup waiting every day of the year.

And in almost every case, the Catholic Worker demonstrates against U.S. war policies that take food, shelter, clothing, and know-how out of people’s worth.

Those who come to the Catholic Worker are helped, no questions asked — unless they’re violent. There are no papers to show.

Finding herself “cast” into this saintly milieu — people attending to the needs of Skid-Row America without asking something in return — Hennessy said she felt like an “outsider.” The further you get into her book, the more you see, paradoxically, that she feels like a homeless person herself.

Hennessy reached the conclusion that, being needy herself, she could not attend to the needs of the more-needy, certainly not face-to-face. She looked at the social DNA that came from her mother, Dorothy’s only child, and realized the truth of what her grandmother said: “How little we know of our parents, how little we know of each other and of ourselves.”

Hennessy’s book is not a Catholic book. It’s about her grandmother and the movement she started of course, but it’s really about how a young woman deals with a delicate social DNA that’s part of her being — a DNA that mandates every person is responsible for alleviating the pain and suffering of every other — without a payoff.

Thus Hennessy’s book is for people who wish to examine their social DNA and how their particular genetic soup drives them toward good or leaves them mired in a swamp of violence.

The lifelong task of figuring this out is what it means to have a spiritual life, to being a “practical mystic,” as Dorothy said. And attending to one’s spiritual grounding, she added, requires at least three hours a day.

If you think this is a hard row to hoe, she would agree; she once said, “Love in action is harsh and dreadful when compared to love in dreams.”

If I were to imagine an inaugural address Kate Hennessy were to give today, following in the footsteps of her saintly mother and grandmother, I know I’d hear: “Love today, love tomorrow, love forever.”