The late Sally Gray, my mother-in-law, used lard for her pies. After I had the pie Sally made for me and her daughter, my wife, at our home on one of her visits, I exclaimed, “This is the best pie I ever had! I want the recipe!” For obvious reasons, this column is dedicated to Sally Gray.

Not surprising to some, a short while back, I had a big debate in the baked-goods aisle at our local supermarket for longer than I wished with a woman who, while I was looking for several baking products, bemoaned not being able to make good crusts. She was looking at Flako.

I told her I could make her a star; she listened but then like a doubting Thomas retorted, “An egg? Are you sure? And a lemon? I don’t want an acidic pie crust! I’d rather have the box.”

I tried to explain; in a few moments I walked away shaking my head and she hers in the other direction; me muttering to myself: “Lady, good luck with your ‘delivery system’ pie crusts.”

By the by, if you are forced to use store-bought crust, Bon Appétit says that tests in their kitchen had the best luck with Pillsbury-brand refrigerated pie crust.

I have looked into more than a few 20th-Century cookbooks to see how chefs/bakers worked with their dough and what ingredients they used. I saw chefs recommend adding vinegar to the water to be added to the flour mixture.

This I have tried myself with good success, using white or appley cider vinegar. Epicurus, as some other recipe sources say, also recommends using a small amount of baking powder to work with the vinegar and give the crust a more airy texture.

Rose Levy Beranbaum, in her “The Pie and Pastry Bible” (Scribner, 1998) also calls for cider vinegar — and also baking powder. To me this is risky because the powder sometimes works faster than I would like.

Some bakers recommend the use of several tablespoons of vodka instead of the same amount of water (or vinegar or lemon in our case). In the case of crusts, as said, the aim is to cut down on the gluten that forms because that is what makes the crust “tough.”

Since alcohol and lemon and vinegar inhibit the formation of gluten, you can make wetter crusts that are easier to work with. Of course, the taste-effects of the alcohol, lemon, or vinegar are burned off and no residue of same remains. The beaten egg gives the crust a more golden look and a more pastry-like taste.

When I make pumpkin pies and need two crusts, or a fruit pie that requires a lattice top, I often make dough for three crusts. It is not a waste; the dough rolls out better; there is more to work with and thus easier; there is a thickness to the crust that lies on the glass plate that gives the pie crust more body but beware that it is not too thick.

This is not a crust that people leave on their plate as you often see when folks eat out the fruit (or whatever the filling) of a pie leaving the crust behind.

Denny Sullivan’s

Unbeatable Pie-Crust Recipe

Passed Down From Sally Gray

How to Make

Pastry-like Pie Dough

And get yummy responses from

your family, friends, guests, and even pets.

THE YIELD

This recipe makes dough for two nine-inch pie crusts. You can halve it to make one nine-inch crust. This is essentially the recipe one might find in a basic cookbook such as “The Joy of Cooking.”

THE PROCESS

Sift together:

2 cups all purpose flour

1 teaspoon of salt

MEASURE (then add to the flour mixture):

2/3 cup chilled shortening like Crisco or lard

2 tablespoons of chilled butter cut into small pieces

WORK

Work the shortenings into the flour with the tips of your fingers until the pieces are the size of nickels or dimes; the pieces of chilled butter will take a bit of effort. The CIA recommends this method, cf. infra.

COMBINE (in a measuring cup)

5 tablespoons of water

juice from one lemon

one egg beaten

MIX

Mix the water-lemon-egg liquid into the flour mixture in a bowl using a fork until all or nearly all the pieces of dough form somewhat of a ball. Gather the pieces together and form a large ball.

PLACE

The dough onto a lightly-floured baking board and cut the ball in half; flatten both pieces to the shape of a hockey puck. Do not over flour.

WRAP

Each piece of dough in a piece of wax paper or plastic bag and put into the fridge for at least 15 minutes. Dough chilled out this way rolls out much easier but, maybe more importantly, chilling the dough allows time for the gluten strands in the flour to relax

TAKE OUT

The first piece of chilled dough and roll it out into a circle larger than the pie plate. Trim the edges so that the dough is circular. Gently fold the dough in half and place it in the waiting pie plate. You can watch Youtube sites to see how this is done. There are several ways to do this, some bakers swearing by one method versus others. NOTE: Roll away from the center, do not roll back and forth; the dough will eventually stick to the pin.

ADD

In the pie, that is, place the fruit or other ingredients for your intended pie (e.g. apples, cranberries, and walnuts).

ROLL OUT

The second piece of dough like you did with the first and place that across the top OR cut the dough into thin (or wide) strips for a lattice pie top.

RECOMMENDED

You might consider putting the ready-to-bake pie in the refrigerator for 10 to 15 minutes to help keep the gluten in check.

ANOTHER NOTE

Chilling the dough before it is rolled out (and the ready-to-bake pie afterward) has to do with gluten and moisture. Again, the chilling allows the gluten to relax which allows for a flakier crust. It also allows available moisture to find its way back into the dough.

In 2000, when I sent the completed manuscript of my “Restorative Justice: Healing the Foundations of Our Everyday Lives” — written with long-time friend and colleague Larry Tifft — to publisher/editor Rich Allinson of Willow Tree Press, he said he was ready to go to press but still had a question about a phrase we used several times: “the political economy of relationship.”

It’s not the time here to explicate our full response to his query; suffice it to say for now that it refers to the governing principle that defines one person’s relationship to another, the conceptions of value he has of the other — whether it be a person, group, or nation — and the principle is deeply embedded in the psyche.

Such conceptions are part of a mental framework whereby we classify others, and devise rewards and punishments for behaviors that jibe with the directives of our ordained hierarchy; it’s a gestalt of sorts and a measure of a person’s moral depth.

When the framework is warped or tilted or off kilter, the assessor’s behavior tends toward the evil part of the good-evil spectrum, manifesting itself in words and behaviors that dismiss, demean, minimize, or otherwise mock the value of the other.

Those who prescribe to such — shall we say — evil, try to obfuscate by couching their words and actions in a propaganda that affords them (the appearance of) cover while shooting salvos at any person, group, or nation they define as inferior and unworthy of human consideration.

The end goal of the evil-minded soul is to tie up, confine, hem in, enslave the other for self-aggrandizement, and the payoff can come in a variety of ways: money, prestige, sex, and any other variable that helps solidify the power complex of the evil-minded soul.

In our Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865, the disagreement was over whether white people had the right to own Black people, use them as slaves on plantations without rights, pay, dignity, or a future of value. In the case of Black women so enslaved, it meant the owner of a plantation had sexual dibs on them anytime he wanted.

The most talked-about example of such enslavement today is Jeffrey Epstein and his accessory to the crime — Ghislaine Maxwell — of operating a plantation for enslaved teenage girls and young women for their sexual pleasure and the sexual pleasure of a cadre of rich and powerful clients who contributed to the finances of their empire. On that plantation, no sugar cane or cotton or coffee was harvested but orgasms (limitless).

Keep in mind that “conceptions of other” is structural and why they have such a powerful effect on behavior; and why so many people went nutso over the Black Lives Matter movement because its main focus was not the working conditions of the Black porter in the galley of an Amtrak train but the underlying structural framework of racism, the steel that defines the structure of one’s ethical framework.

Thus, in the hierarchical ordering of races and ethnicities white people assign greater value to themselves than to people of color, a disease diagnosed as white supremacy.

Women are well versed in how value is assigned to genders and sexes because historically men with power and money, who control access to reward systems, assign greater value to themselves than to women — as is happening right now as sexually-straight (white) men enforce a value system that assigns greater worth to themselves than to their lesbian, gay bisexual, transgender, and queer neighbors.

In his 2018 manifesto “Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World,” the veteran journalist Anand Giridharadas challenged whether those in “the corridors of political power, should be allowed to continue their conquest of social change and of the pursuit of greater equality.”

He assured us, “The only thing better than controlling money and power is to control the efforts to question the distribution of money and power. The only thing better than being a fox is being a fox asked to watch over hens.”

When efforts are made to question or dismiss or minimize the reality of someone else’s pain and suffering, define it as fake news, then Orwell’s 1984 has come.

As a Great and Powerful Wizard was exposed as a fraud when Toto pulled back the curtain in the throne room of Oz, so now the current President of the United States is bereft of any redeeming psychological, philosophical, or religious value having supported Nazi-like ideologues like David Duke and Nick Fuentes, and after taking away the life-supporting aid the U.S. Department of Agriculture made available to the poor through its Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Then there’s the gasoline he kept pouring on the flames of “birtherism” accusing Barack Obama, running for president, of being an alien. How he gloated in 2010 when Joseph Farah’s WorldNetDaily filled a 14 x 48 foot highway billboard in South Gate, California displaying his hidden hate in giant capital letters: WHERE’S THE BIRTH CERTIFICATE?

In her memoir “Unhinged,” Omarosa Manigault Newman, a White House adviser to Trump said, when he hosted the TV show “Celebrity Apprentice,” he frequently used the N-word and that tapes of the show have proof.

And, though she says she herself never heard him say it, she knew “Using the N-word was not just the way he talks but, more disturbing, it was how he thought of me and African-Americans as a whole.”

The current president could not shake the fact that someone he would use the N-word to describe, with degrees from Columbia and Harvard Law, who ran the “Harvard Law Review” was going to be a president of our United States.

Which gets us to the point of all this. Last Thursday, Mr. Trump through his propaganda machine shot into the stratosphere images of the former president, Mr. Obama, and his wife, Michelle, as apes, gorillas, niggers, while the once popular song “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” played in the background of gorilladom.

It was the KKK in a 21st-Century disguise shrugging off the pain of anyone hurt by it as “Fake Outrage.”

As a country unhinged by current civil-war-like conditions — incessantly fueled by Mr. Trump — far too many ordinary citizens, just regular folk, fail to realize that everyone in a nation so besieged must engage in deep self-analysis. In her 1942 classic “Self-Analysis,” the great psychoanalyst Doctor Karen Horney offered a method whereby people can face up to their complicity in, shall we say, evil.

An article in the Oct. 10, 2024 issue of “The Conversation” drew attention to “Why Trump accuses people of wrongdoing he himself committed — an explanation of projection.” And projection, as we know, is a neurotic affliction whereby a weak person unconsciously attributes his own unacceptable feelings, thoughts, or traits (like jealousy, insecurity, or anger) onto someone else — persons or groups — instead of self-analyzing where the governing principle of such fascism resides.

In a fraud case against Trump University in San Diego in 2016 the aforementioned Mr. Trump said the presiding judge, Gonzalo Curiel, hated him: “I have a judge who is a hater of Donald Trump, a hater” because Curiel was “Hispanic,” a “Mexican.”

His conceptual gestalt had Judge Curiel in a corral with all the other Mexican rapists just as he had classified the Obamas and every African American on earth as an ape or gorilla.

Occam’s razor in cutting to the chase of logic says a swamp cannot drain itself. If you were put on the stand in a courtroom right now and were asked to describe the governing principle you live by and how that came about, who would you describe as unworthy of human consideration?

In the winter of 2021, the Washington-based Pew Research Center conducted a survey of adults in the United States wanting to know who among them had read a book in the past year — or even part of one.

The country had been in complete lockdown the previous year and it was thought the great hiatus from social life had offered folks a chance to catch up on the Danielle Steel or James Patterson collecting dust on their end table.

The survey revealed that a quarter of those interviewed said they never saw a dust jacket, never mind read a chapter or two of a book: 23 percent to be exact.

And when the researchers looked at how education affected who did what, they saw only one in 10 with a high school diploma or less education, had read a book. Those with a college degree or grad school were four times more likely to have done so.

Jimmy Kimmel — host of the late-night television show, whom authoritarian executives (political and corporate) kicked off the air for saying the federal government under Donald Trump had turned fascist — thought Pew’s data were skewed, saying fewer people had read a book than was reported.

He sent a video team onto the street in front of the studio to ask passersby whether they had read a book or part of a book in the past year seeking to verify Pew’s data.

Three years earlier, in 2018, he did the same when he had his crew ask passersby: “Name a book, any book.” People could have said the Bible and been done with it, but the dozen or so interviewed could not come up with a single title.

In Kimmel’s 2021 survey, one man said he had not read a book “not even in my college life, ever.” Amazed, the interviewer said, “You went through college not reading a single book?” He said, “Yes.”

Ask any college professor about how hard it is to get students to read these days and they will describe forms of outright resistance.

Such willfulness is one of the reasons the United States has become a nation of lumpenproles, to bring Marx and Engel into the mix — the two who coined lumpenproletariat to describe the dispossessed in a society.

But dispossessed is my word. In 1848, Karl and Friedrich in their “Manifesto of the Communist Party” said lumpenproles were ragged people, scoundrels, knaves, the unwashed, alienated freeloaders, people who feed on the social capital of the society but never chip in.

The same can be said of those who don’t read books — forget studying — who, like the lumpen, never gain an overview of the forces that shape the society they live in, and thus never grasp how such forces shape their own life: how good they feel, the kind of work they do; whether they’re free from enough worry to catch a moment’s peace of mind.

Not-reading is not just a refusal to engage in personal development, it confounds the critical relationship that exists between how much social capital a society has to distribute to its citizenry and how happy its people are; the Social Happiness Quotient Factor (SHQF) of a society rises and falls according to how well collectively-owned resources are distributed to all — and without resentment.

Social capital — as discussed in these pages before — refers to the relationships, the networks, the connections people have that foster their personal happiness while supporting the health of their society’s institutions: schools, hospitals, churches, synagogues, even families.

Social capital is a glue, a cohesiveness, a connectedness that makes people feel good about who they are, where they live, the work they do, the relationships they have at all levels of the social ladder. It might derive from something as simple as the camaraderie felt at a summer picnic held at the Elks lodge.

Reading contributes to social capital because the reader gains an overview of: (1) how existing social, political, and economic conditions affect his everyday life, whether they free or constrain his behavior, dismiss his dreams; and (2) how the social institutions of the society — when they are compassionate — promote the psychological health of everyone up and down the social ladder: and the more informed a person is on such matters, the less likely he is to make mistakes that drain the community’s collective resources.

Author Rudine Sims Bishop, an emerita at Ohio State University, says in her 1990 essay “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors” that books can change people on a number of levels.

On the most basic, she says, the book can serve as a mirror in which the reader can see himself as he is, can assess his happiness, the degree to which he found, and is living out, his purpose in life, what he was called to do. Some books have strong self-reflection-producing powers.

Those who succeed at this level, Bishop says, soon see the mirror become a window that displays the political, economic, and social forces out there in the world, allowing the viewer to measure to which extent those forces support or diminish his (and his society’s) well-being.

After that, the book can become a glass sliding door through which the seer can still see the world out there, but is given a chance to turn the handle and walk out into that world to be a person doing good.

This might include the revolutionary hope that the needs of all — especially the dispossessed — will be taken into account when life-supporting resources are distributed — something as simple as a few food stamps to tide the family over until better days arrive.

Such consciousness knows that happiness is not a scarce commodity, that there’s far more than enough for everyone to receive a just share — and how one defines who is and who is not worthy of such a share is a measure of that person’s moral depth.

But now, as fewer and fewer people read, we see the conceptual framework of what constitutes the common good — dissolve proportionately: the weak, the uneducated, the lumpenproles, the dispossessed — call them what you will — keep falling to the fringes of society, making them prone to buy the sales pitch of authoritarian magnates who promise security by offering to take over the victim’s thinking as well as moral choices.

The great late American poet Adrienne Rich (1929-2012) tackled this issue in her 1978 collection of poems “The Dream of a Common Language.”

As a lesbian, Rich said her love as a human being was disvalued so she and others like her were treated as aliens in their own country, barred from contributing to (never mind receiving) social capital at all levels of relationship — society, community, neighborhood — except for their family of outsiders huddled together for mutual support.

A common language are words that make understanding other persons and groups who do not share a native (same) language possible; it’s a third language, a bridge language, a lingua franca.

It’s a language of economics because the needs of all tongues, all competing parties, are taken into account; those with ears to hear are given strong support to walk through the sliding door and help distribute life-preserving resources to all, especially the dispossessed.

History says those who refuse to learn and practice the common language are prone to become “part of a bribed tool of reactionary intrigue” as Marx and Engel put it.

Which is the case in America today as the lumperproletariat have become the bribed tool of intrigue of a fascist dictator and why Jimmy Kimmel said in his Christmas message to the UK: here “tyranny is booming.”

In his column in last week’s Financial Times, Ed Luce agreed, asserting that “America’s barbarians [are now] inside the gates,” which requires inverting what former President Gerald Ford said in his inauguration address on Aug. 9, 1974, that is: our long nightmare is not over.

Requiescamus in pace, those of us who still consider ourselves American citizens.

For Jim and Wanda Gardner

When you strip away the tinsel from the Christmas message, you see right away that, when you buy into the child in the manger — the Nativity Scene — you also buy into the whole 33 years of the child’s life.

Thus, on Christmas morning you not only sing, “The blessed angels sing” from “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear” but also chant the beloved Negro Spiritual, “Never Said a Mumbalin’ Word” which goes:

“He bowed his head and died …

and he never said a mumbalin’ word;

Not a word, not a word, not a word.”

And if its refrains are unknown to you, there is tenor Anthony León’s performance of Moses Hogan’s arrangement, Elvin Rodríguez on piano.

I’ve not seen anything on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s take on the birth of the child Jesus but you can see from “The Brothers Karamazov” that he’s quite familiar with the whole 33 years of his life

In the story, a woman with money asks an elderly monk, Staretz Zosima, if it’s possible to prove the existence of God.

The priest says no intellectual argument or explanation seems to exist, but proof can be found in the practice of the “active love” Jesus announced on Christmas Day.

She said she thought of becoming a nun living out the “dream of forsaking all … full of strength to overcome all obstacles. No wounds, no festering sores could … frighten me. I would bind them up and wash them with my own hands. I would nurse the afflicted. I would be ready to kiss such wounds.”

Which is how Pope Francis treated the poor in his neighborhood inviting them to his apartment for meals — the apartment the digs of a simple man. He could never imagine throwing a grand ball for the rich and greedy in “Great Gadsby” style at a Mar-a-Lago estate while scads of poor — not far from where the champagne was being poured — were clawing away to put a decent meal on the table.

And the Washington billionaire who sponsored the gig is the guy who took away coupons from those souls that we, as an assembled Congress, had allocated for them through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Dostoevsky’s rich lady was also a retributionist in that she wanted to be paid like “a hired servant, I expect my payment at once — that is, praise, and the repayment of love with love. Otherwise I am incapable of loving any one.”

It’s the quid pro quo ethic of an unconscious waif reflecting the economically-debilitating ethic of do ut des: I give so you can give something in return: feelings of reciprocity we all grapple with.

Zosima tells the woman to stay in her dream world because “love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing compared with love in dreams. Love in dreams is greedy for immediate action, rapidly performed and in the sight of all.”

Dorothy Day, the founder (with Peter Maurin), of the Catholic Worker Movement spent 50 years of her adult life offering food, shelter, and clothing to those in need, in person and face to face: A mumbalin’ word never left her lips.

In “The Long Loneliness: The Autobiography of Dorothy Day,” she tells how she came to embrace the child of Bethlehem, and was able to remain un-distraught by the loneliness that comes from embracing a love that seeks nothing in return.

Charles Dickens in “A Christmas Carol” shows he knows well the meaning of harsh and dreadful love. Indeed, he’s the fifth gospel of the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, and Charles.

And “A Christmas Carol” offers far greater insight on economics than Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations.” Scrooge’s transformation is the Sermon on the Mount grounded in the day-to-day language and thought of the poorest of the poor.

One Christmas Eve two men come to Scrooge and ask for a donation to help the “Many thousands [who] are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts.”

Scrooge snaps, “I can’t afford to make idle people merry … they had better [die], and decrease the surplus population.”

The story came out in 1843 but Scrooge is among us still in Elon Musk and his genre who, following orders from the President of the United States, shuttered the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) that was offering life support to those in dire need — which has resulted in what Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates called “killing millions.”

A flabbergasted Gates told “The Financial Times” he still could not absorb, “The picture of the world’s richest man killing the world’s poorest children.”

“I’d love for him to go in,” Mr. Gates said, “and meet the children that have now been infected with HIV because he cut that money,” funds to allow every Tiny Tim in the world to have a life.

Being a billionaire is not the disease that causes savagery; Mr. Gates — himself once the richest man in the world — just pledged to give away his final $200 billion through a foundation he and wife, Melinda, started for “the cause of saving and improving lives around the world.” They’d already donated billions.

“People will say a lot of things about me when I die,” Mr. Gates said, “but I am determined that ‘he died rich’ will not be one of them. There are too many urgent problems to solve for me to hold onto resources that could be used to help people.”

How radically opposite is the billionaire in the White House calling Somalian immigrants “garbage;” a woman newspaper reporter a pig; another “ugly,” another “stupid” and endless other slurs reflecting mental savagery.

It’s the same guy heard on tape in October 2016 saying, “When you’re a star they let you [do this] … do anything … Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything.”

In his classic “Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography,” the revered Jesus scholar John Dominic Crossan says he understands how people treated as pigs and ugly bags of garbage can feel like they got “a boot on their neck … [and] envision two different dreams. One is quick revenge — a world in which they might get in turn to put their boots on those other necks.”

But, Crossan says, there’s another “world in which there would never again be any boots on any necks.”

In all his years of work on Jesus, Crossan kept coming back to the child of Bethlehem embracing a message so radical that Roman and Jewish authorities silenced him for it by execution.

The Christ child in the manger, anthropologist James Scott says, was calling for “a society of brotherhood in which there will be no rich and poor, in which no distinctions of rank and status … will exist … the abolition of rank and status … the elimination of religious hierarchy in favor of communities of equal believers. Property … held in common and shared. All unjust claims to taxes, rents, and tribute … nullified … a self-yielding and abundant nature as well as a radically transformed human nature in which greed, envy, and hatred will disappear.”

And yet Good Friday disbelievers continue to jeer: “Save yourself, if you’re God’s son! Come down from the cross!”

Jill Jackson and Sy Miller wrote a hymn that countermands the savagery of the current President of the United States whose mantra persists: “If they screw you, screw them back 10 times as hard.”

Jackson and Miller sing:

Let there be peace on earth

And let it begin with me;

Let there be peace on earth,

The peace that was meant to be.

They are the angel of Christmas today: “Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people.”

All people. ¿Entiende?

Thus, Happy Hanukkah; Happy Kwanzaa; Merry Christmas; Happy Midnight Winter Sun — and whatever words anyone else has to celebrate the love Jesus brought on Christmas day.

For Jimmy Kimmel

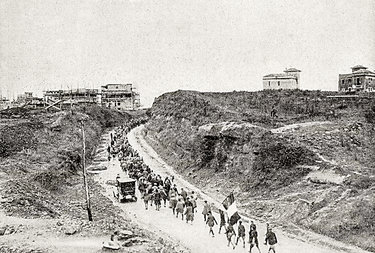

On Oct. 28, 1922, more than 30,000 black-shirted paramilitary fascists — the Italian word is squadristi — under the leadership of Benito Mussolini marched into Rome to take control of the capital of the Italian nation.

Historians refer to the insurrection as “The March on Rome,” which seems to have been a harbinger of the mob attacking the Capitol of the United States on Jan. 6, 2021.

Two days after the take-over, the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III — with the support of the social elites of the nation, the corporate world, and the military — ceded power to Mussolini. On Halloween, the dictator formed a government that soon became the one-man-rule of il duce.

In her profile of Signore Dux, in “Fascist Spectacle: The Aesthetics of Power in Mussolini’s Italy,” cultural sociologist Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi says the dictator saw himself as “God’s elect;” a “savior;” a homo unus — the one and only who could help Rome be great again.

Was that not a harbinger as well of what was broadcast across the United States in 2016 when the country’s current president said he was going to save America because “I alone can fix it;” and in November of the following year, when the cult personality of homo unus was solidified, added: “I’m the only one that matters.”

After taking control of the capital — Italy’s legislators having folded like a house of cards — Mussolini turned to his propaganda tsar, the “philosopher of fascism,” Giovanni Gentile — officially the Minister of Public Education — and ordered him to soak every Italian kid in every school in the nation with the hose of fascist doctrine.

He wanted under his control every Italian kid when he turned 6 until he reached 16, because he knew, by then their veins were plump with totalitarian Newspeak.

Gentile’s treatise “Manifesto degli Intellettuali del Fascismo” “The Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals,” served as a blueprint for the political and ideological underpinnings of Italian fascism. The idea was to get control of the big minds, the smart guys, and have them work on the hoi polloi below.

The work is a justificatory rationalization for the black-shirted guards of the National Fascist Party (PNF) using violence against those who refuse to submit to psychological debasement.

In a section called “Fascism and the State,” Gentile reminds the reader that a “victorious Nation was now on the path to recovering its financial and moral integrity” and by “recovering” he meant MRGA “Make Rome Great Again.”

In no time, the curricula in schools were ablaze with fascist lingo. British writer Anthony Rhodes, in “Propaganda: the art of persuasion, World War II” (Wellfleet Press, 1987) says, “very soon, at least 20 percent of the curriculum in the elementary schools had been revised in this sense, teaching the adolescent from very early days his duties as a Fascist citizen.”

When the school-day started, the kids joined in on the “Giovinezza,” the national anthem of the Italian National Fascist Party, the PNF, Partito Nazionale Fascista.

Its refrain is:

Youth, youth,

Spring of beauty,

In Fascism is the salvation

Of our freedom.

At the university level, students were “urged” to join Gruppi Universitari Fascista, if they hoped to get somewhere in life. ¿Entiende?

As the totalitarian disease spread across the nation, the citizenry were forced to retreat to their minds for emotional support—as Orwell says people did in “Nineteen Eighty-Four”—and as many Americans in the United States are doing today for psychological relief.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a movie is worth a million and no director has put more millions on the big screen addressing the insanity of fascism than Federico Fellini.

He hits its coercive socialization in the face in “Amarcord,” his big-screen portrayal of him growing up in Rimini, a small town on the Adriatic coast.

Amarcord is dialect from the Romagna region where Rimini is located and means “I Remember.”

Thus, every frame of the memoir-driven jewel has the maestro shooting off Roman-candle images of every kind of person you can imagine living in a small town in 1930s Italy.

Fellini told potential viewers to keep their eyes peeled for the part when a fascist government official, a federale, comes to town and rouses the locals to march like soldiers in double-time-step and sing songs honoring the very power enslaving them; he said the scene is “the central, irreplaceable, indispensable episode” of the movie.

The artistic genius of “Amarcord” was duly acknowledged by the film world by being awarded the 1973 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. It’s on the top-10 list of untold thousands — cineastes and otherwise — and close to the top of mine.

Though the film is filled with humor and an irony that reaches the heart, there’s sadness in seeing Rimini’s pedagogues, the Latin, Theology, and Science teacher at the local school — practitioners of the old-time rote method of learning, unaware of the lives of the young men before them — donning black shirts and pants and goose-stepping boots to show the federale how much they loved kissing the emperor’s ass.

For more than a decade I’ve told members of my memoir-writing group at the Voorheesville Public Library to view “Amarcord” and use it as a rod to measure how well they extricate truth from the past and put it down on paper with clarity. So far, all I’ve heard is crickets.

Mussolini encouraged acts of intimidation, ordered beatings and the breaking of bones, even murders. Anyone who blinked the wrong way, they said, was subject to the manganello (the billy club) and castor oil.

Castor oil? As “Amarcord” progresses, the black shirts drag a local into headquarters for questioning — an older family-man, a brick-layer-cum-foreman — and accuse him of having thoughts contrary to the regime.

To force the sorry soul to come clean — no pun intended in any way — they force castor oil down his throat, a personally-denigrating torture Mussolini’s black-shirted employees used to embarrass infidels by causing them to lose control of bodily functions.

Remember: Castor oil is a powerful laxative.

Thus our oil-soaked brick-layer-cum-foreman didn’t get past the front door before messing his pants and suffering the humiliation the fascists sought to achieve.

It was the [crazy] Italian poet Gabriele D'Annunzio who introduced the regime to castor oil, as well as to the fascist salute, and black shirts, and balcony speeches, and other forms of drama made to force the ethically insecure to cave. Some say D'Annunzio was Mussolini’s John the Baptist.

Fellini said understanding fascism was no big thing: it derives from “a provincial spirit, a lack of knowledge of real problems and the rejection of people, whether out of laziness, prejudice, greed or ignorance, to give their lives a deeper meaning.”

He said “Fascism and adolescence … [were] permanent historical phases of our lives. Adolescence is of our individual lives; Fascism is of the national life: [the desire] to remain, in short, eternal children.” Pueri aeterni.

No matter what level one has reached in knowing the basics of history, no one has not heard of the saying: When we fail to pay attention to the evil our forebears did, we pay double because we repeat the same evil by becoming it incarnate.

The Oregon-based American novelist Chuck Palahniuk has rued, “If you watch close, history does nothing but repeat itself. What we call chaos is just patterns we haven't recognized. What we call random is just patterns we can’t decipher. What we can’t understand we call nonsense. What we can’t read we call gibberish. There is no free will.”

To translate such dystopian talk, I turn to our beloved national treasure, Mr. Pete Seeger — blacklisted for espousing beliefs under another regime — in his 1955 American classic “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”

In the somber tone of a Greek chorus he inquires:

When will you ever learn?

When will you ever learn?

For John Francis Sullivan Jr.

My life really is paying attention to words: how people use them; the rhythms of their speech; and ferreting out circus-barker, pulling-the-wool-over-your-neighbor’s-eyes, con-man talk.

The latter way of speaking is problematic because, as it becomes habituated, it diminishes the happiness of the speaker as well as negatively affects the society he’s living in.

And, when such words reach Orwellian newspeak proportions, the society’s chances of evolving grow dim, having morphed into something it once despised.

How a person talks is who he is. How a society talks is what it is. Words are deeds with consequence.

That’s what the Canadian-born American social psychologist Erving Goffman was trying to get at in his 1956 genius piece of work “The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.”

Any training institute set up to help people embrace reflective self-analysis — and using Goffman’s book as a text — would have each person get up before the group and describe how he presents himself to the world — or thinks he does — declaring what words he uses to ensure his needs will be met — and of course saying how he came by the words in the first place.

When I ask people what words they use most, what their vocabulary looks like, I hear in a stunning silence: Wha?!

Of course, as a poet, I pay attention to how I speak all the time. It’s my job, my calling; being a poet is non-stop self-reflective study of the language I use and attentiveness to the words others use to ensure their needs are met.

Often overlooked is the correlation between how well a society does in the meeting of the needs of (all) its members and the happiness quotient of that society. The fewer the needs met, the more disgruntled people there are, the unhappier the society.

When we inventory the words a society uses and examine the content of the message(s) they contain, we get a picture of the collective speech of the society that ultimately is a measure of the ethical and moral depth of its members.

Anyone with half a wit knows certain words offer no path to the future because they’re war-ridden; born of a clinical depression, they spawn dystopian blare-horns whose stock-in-trade is fanning civil conflict in the interest of effecting social-suicide.

William Carlos Williams, one of America’s greatest poets — a key link in the genealogical tree of American poetry — next in line after Whitman — told poets to pay attention to how people speak every day — to the vernacular — words they use without thinking.

Of course some words raise the happiness quotient of a society, while others tear it down; the difference is in how many people in the society wake up each day and say “Wow, man, gimme some more of what I had yesterday! I can’t wait to get out of bed and greet the day. My work is a calling-in-life come true. I make more money than I need; call me Monsieur Heureux!”

Doctor Williams — he was an M.D. as well as a poet — told poets that, when they come upon vernacular words, to write them down, then decode them, because they are a mirror of the soul of the person saying them as well as the community, group, society, in which they’re being said.

And “words-as-mirror” is not a sociological construct but genetically-based, DNA saying this is a place where the nervous system does not feel threatened so the tongue can lay down all verbally-abusive words as a way to get its needs met.

To minimize making costly (false) moves, all organisms — right down to the amoeba — know documenting every word of daily speech must be beyond reproach; lying or contradicting the Laws of Physics in any way is fatal to personal well-being and the continuity of a caring community.

A GPS does not say turn left when it knows the grocery store you’re looking for is on the right; the system is geared to ease tension, to ensure the traveler reaches his destination without consternation.

And though our poet-doctor did produce an epic poem, “Paterson,” he never turned from the vernacular speech of everyday. As an ethnographer of the streets, he recorded what he saw and heard and felt as he made his rounds to and from his patients’ homes.

In his poem “A Negro Woman,” the vernacular of life bursts forth in a Black woman who’s [original margins adjusted]:

carrying a bunch of marigolds

wrapped

in an old newspaper:

She carries them upright,

bareheaded,

the bulk

of her thighs

causing her to waddle

as she walks

looking into

the store window which she passes

on her way.

What is she

but an ambassador

from another world

a world of pretty marigolds

of two shades

which she announces

not knowing what she does

other

than walk the streets

holding the flowers upright

as a torch

so early in the morning

When we pay attention to words on a regular basis, we soon get a peek into the logic, the ideology underlying them, making it easier to decode the intentions of the message-sender. The trade of the poet is always to be in harmony with the Laws of Physics in finding the freest words available.

And free means speech that comes with no baggage, baggage defined as duplicity, as cheating on what appears before the eyes, as contradicting meanings accepted since the beginning of time; when Cain killed Abel, they called it murder; they said one and one were, and would always be, two.

Thus, in the interest of truth, poetry transcends all political ideologies.

You can see why, therefore, any poet of consequence in the United States was extremely troubled on Jan. 6, 2021 when he saw: (1) a riotous mob breaking and entering the capital of the United States of America and killing policemen and policewomen whose job was to protect America from invasion; and (2) the man who incited the mob — the President of the United States — calling the day a “day of love.” The eyes of every poet alive were blind-sided by such Newspeak that openly defied the Laws of Physics.

The poet therefore — I’ll speak for me — is always searching for the exact words for what appears before the eyes or is felt within, relying on eternally-accepted rules for assessing the weight, size, shape, color, even purpose of a thing.

If Doc Williams’s Black woman saw what he said about her, she would have thought she was looking in a mirror.

The Hippocratic oath of the poet requires him, her, them, to use the truest, most accurate word to say what appears before the eyes, or is felt within, the seer obligated to wade into the pool of unconsciousness and fish out the only word that exists to address the reality at hand.

On the level of ethics, the First Commandment of the poet is: Thou shalt not distort the life of any one or any thing for the sake of power or money or any other quid-pro-quo: distortion leads to personal unhappiness and enlivens dystopians — hell-bent on destroying the social cohesion of a society — to thrive.

Right now, for me, our poet du jour, well, I feel I’m in ancient Rome as hordes of barbarians are standing at the gates ready to take the city down.

What’s it like for you?

Walt Whitman appeared in a dream tonight

In front of a mausoleum dressed in sadness

Weeping for the lost soul of America.

Uncle Walt! Uncle Walt! I appealed

Weave a poem of hope and restoration

Raise up heroes from the dead

Like sprigs of green in April.

Poor Walt, tears fell upon his hoary chin

And words slipped out of silence:

Drop your swords, America! On your forge

Forge ploughs of wheat and honey

The gentle murmurings of a tender heart.

Drop your guns America! Raise your arms

In prayer with thanks for all received.

Celebrate the laws of Eros

Come to clothe and feed the cherished ones,

Feed your neighbor with the crust

And crumb of labor’s sweat.

Let no soul be born or die as poor

Every debt the debt of all

Every gain the gain of every other

Even the minds of the mad say so.

Celebrate the common weal, remember

The body wins without division.

Heed the coo of the mourning dove

Whose mindful joy declares:

Nothing is the end and means of life

Nothing is its end and means.

For Zio Pietro Bonventre

When I saw an essay by Joan Didion in the Dec. 5, 1976 New York Times Book Review called “Why I Write,” I was taken in right away.

It was because years earlier I read a piece by the grand master of the just phrase, George Orwell, with the same title. His piece appeared in the Summer 1946 issue of the British quarterly “Gangrel.”

Toward the end of my Sept. 24 column last year, I alluded to the importance of the essay.

The topic is forever compelling because, by looking at what a writer has to say — even a novice in the dock — about the spark that projects him to sit with pen and pad and share his musings with the world, well, it’s a look into the person’s psyche, like overhearing him speak from the couch in his therapist’s office.

And whoever seeks in earnest to answer “Why do I write?” or maybe just “Why do I speak the way I do?” soon finds himself in the deepest dimensions of his being.

Finding the right words — right as in exact — is not an easy task because words begin as neurons sparked by an electrical impulse — instigated by protoplasm — each impulse containing a message.

And taking down the messages without interfering is the work of the writer — the poet does it directly — and requires the discipline of being a good listener.

The poet must have the patience of a person waiting in a long line at the supermarket that’s hardly moving and not suffer a jot of irritation.

The great American composer John Cage used to say waiting in line was an opportunity to practice (the virtue of) patience, a dharma I adopted long ago.

The protocol of listening requires that the first thing the writer/poet/speaker does is go to the thesaurus of his soul — the deep state of subconsciousness and receive the symbols as they are being ignited, hopefully confirming what the person’s eyes are saying is in front of them.

And as the words form, they express, reveal, the message the electrical impulse was sent to say, and, when caught right off the hoof, as it were, they speak to a collective dream every person in humankind shares.

Those who embrace politically conservative ideologies never go near this level of being because “collective” is anathema — especially after John Wayne rode his horse across the American landscape — and thus they reject all conversation having to do with what people and communities need to thrive.

It might seem strange that, while Orwell was writing “Why I Write” he was also composing “1984,” the quintessential story about what it’s like to live in a world controlled by a fascist dictator — a Big Brother, a King, or a Tsar — what the people in the United States are experiencing now.

The connection is understandable because in the novel Orwell was talking about the radical pain and suffering Big-Brother-types cause while in the essay he was telling people what they have to do to stop being shat upon. Like a loving uncle.

For starters, he says he’s like any other writer because all writers seek to “push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s ideas of the kind of society they should strive after.”

From 1922 to 1927, he served as a policeman in Burma, which he wrote about in “Burmese Days,” having come away knowing that people sell other people out when trapped inside a system that undermines the better side of human nature.

Those who know Orwell’s life know he garnered the courage to go to Spain in 1936 to fight in the Spanish Civil War to halt the fascist invasion of Big Brother Francisco Franco and, while on the front lines fighting side by side with his comrades, took a bullet in the throat.

The war experience he says “turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood.”

Thus “Every line of serious work I have written since 1836,” he says, “has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism.”

And he knew “it [was] invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.”

Gandhi-like, he spent his waking moments waking people up to the importance of creating, living in, celebrating a society — convivial communities — that are designed to meet the needs of every one of its members; that’s what he meant by democratic socialism not the party-line spiel of the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist politburo of Putin.

In Orwell’s democracy, leaders and citizens create institutions and programs to help reduce the pain and suffering of all by taking into account what people need, listening to the stories of others as a principal part of their ethical protocol.

Thus, when I read what Joan Didion said in her “Why I Write” about the messages her neuronic impulses sent to her, I was chagrined. She sounds like an adolescent schoolgirl.

She starts out with: “Of course I stole the title for this talk, from George Orwell.”

And “One reason I stole it,” she adds “was that I like the sound of the words: Why I Write. There you have three short unambiguous words that share a sound, and the sound they share is this:

“I

“I

“I.”

Is that not adolescent schoolgirl talk?

Like Orwell, she too writes, Didion says, because, “In many ways, writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind.”

But then she goes off the rails belying Orwell’s empathy.

The writer, she says, is engaged in “an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions — with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating — but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.”

Secret bully? Invader of the “private space” of someone searching the thesaurus of his soul for meaning? Is she equating the writer with Big Brother?

I’ve read nearly every word Orwell wrote and I’ve never seen him as anything other than an empathetic seanchaí speaking in behalf of universal happiness.

And then, when we turn to the writer Janet Malcolm, we see kerosene poured on Didion’s fire. Malcolm says: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.”

She says every writer is “a kind of confidence man, preying on people's vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse. Like the credulous widow who wakes up one day to find the charming young man and all her savings gone, so the consenting subject of a piece of nonfiction learns — when the article or book appears — his hard lesson. Journalists justify their treachery in various ways according to their temperaments. The more pompous talk about freedom of speech and ‘the public’s right to know’; the least talented talk about Art, the seemliest murmur about earning a living.”

Orwell never failed the test of humility; he said, “And it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality.”

You can see why he’s my main mensch.

More about “1984” coming next in The Altamont Enterprise available at your favorite newsstand.

It’ll address the Big Brother stressing the world out now.

For two great teachers:

Arthur Willis and Lydia Tobler

Dictionaries of the English language say “provenance” refers to the mapping of the ownership of a work of art — such as a book or painting — from its origin through different owners to the present day.

While a work of art has intrinsic value, oftentimes those who owned the object over the years, because of their importance, raise its market value, sometimes significantly. Regular viewers of the “Antiques Roadshow” on PBS know how it works.

I have a story about the provenance of a work of art that I think is as good a local-history-provenance story as you’ll find.

And it has to do with a book by a New Scotlander, Anna Hendrick Newhart, titled “Relations, Recollections and Reflections of the Hendrick Family,” which appeared in a severely-limited privately-printed edition in October 1936. That is, there may be only one copy alive.

I first heard of the work in 1985 when I began researching the history of the town of New Scotland’s prize agricultural gem, the Bender Melon Farm, which was located where New York State Route 85A joins Route 85 at the Stonewell Plaza. The properties of Fred the Butcher and Stonewell Plaza were once part of the farm.

Our paper, The Altamont Enterprise, published the findings of my research, half of the text in the August 28, 1986 issue and the rest a week later — all under the supervision and enthusiasm of our esteemed then-publisher, Jim Gardner.

At the time, I was told both issues sold out. I don’t know if that’s true but I do know there were a lot of people alive then who were familiar with the farm and who were interested in the history of the town they lived in: They knew of the farm’s fame.

Recognizing the value of the work, the New Scotland Historical Association asked to publish the text that appeared in The Enterprise and did so in a 40-page monograph called “Charles Bender and The Bender Melon Farm: A Local History” (1990).

When striving to find out all there was to know about the farm, I talked to agèd locals Jane Blessing and Sam Youmans and others, one of whom said — I no longer remember who, my memory offers a mea culpa — that Charlie Bender started his seedlings in the greenhouses at Font Grove Farm on Font Grove Road overseen by the renowned Colonel James Hendrick since the mid-19th Century. He had 21 large greenhouses known as “Font Grove Nurseries.”

And either that person or someone later said that the information about Charlie Bender’s seedlings came from a family history book written by Anna Hendrick Newhart, the daughter of the Colonel of Font Grove Farm who knew about her father’s relationship with Bender.

I no longer remember who told me about the book but somebody — again mea culpa — said the tome was in the possession of an antiques dealer in New Salem by the name of George Matuszek.

I got George’s number and called right away. I told him about my research and that I heard he had a book that included information about Charlie Bender starting his seedlings in the greenhouses at Font Grove Farm.

He knew what I was talking about, said he did own the book but no longer had it in his possession — my heart sunk.

He said he had loaned the book to the famed writer William Kennedy who had just come out with “O, Albany! An Urban Tapestry” (1983), a series of essays about the historical goings-on in the city of Albany way back when.

George told me he figured that, since Kennedy did something on the locals in Albany, he might want to do the same for New Scotland, an “O, New Scotland!”

I said, “George, have you lost your mind! Nothing happened in New Scotland!”

But he did say that, when Kennedy returned the book, I could use it.

I told him I knew Bill Kennedy since the early ’80s when a group of writers, journalists, college profs, etc. used to meet every Thursday at the Marketplace restaurant on Grand Street in Albany to drink and chat and share work, and that I had been blessed to be among them.

I told George that, if it was OK with him, I’d contact Bill and see if I could get the book back sooner. He said: No prob.

I called Bill’s daughter and she said her father would meet me in a few days — I no longer remember the timeframe — at the famous Legs Diamond house at 67 Dove Street in the city of Albany that Bill bought during his rabid research to write his classic “Legs,” which came out in 1975 (Coward McCann and Geoghegan).

George said, “Well, if you’re going to meet the guy, how about getting me a signed copy of one of his books?” I said: No prob.

Straightaway, I went to The Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza and bought a paperback copy of Kennedy’s lyrical “Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game” (1978, Viking).

I met Bill as scheduled at the Legs house — we chatted for a half hour or so — I got the book and before leaving said, “Bill, would you sign this copy of Billy Phelan” and told him who it was for; and he wrote something like “Best Wishes George Matuszek; Cordially; William Kennedy” in a pretty clear hand.

If one of George’s daughters has the copy, she can say exactly what the wording is.

And with respect to what I started out to find, the Hendrick-Newhart book, on page 46, says, “For a year or two he [Charlie Bender] tested his seeds in the Font Grove greenhouses.”

So my original sources on the matter were correct, not only about where Bender started his seeds but where the information came from.

I should mention as well that, when I visited George’s home to present him with the autographed copy of the book, he said something surprising, “Hey, Kennedy didn’t sign this! You did!” That kind of logic.

I took a deep breath until my better angels showed to say what George really meant was he could not believe he actually had a signed copy — to him — of a William Kennedy classic.

But I found George even in his most businessman-like moments a most congenial fellow and we got along fine.

When the results of my research appeared in The Enterprise, the mayor and trustees of the village of Voorheesville asked if I might like to take on the official duties of the historian of their village, an invitation I gladly accepted.

Locals know that in 1989 I came out with a serious history of Voorheesville, published by the village — thanks to Mayor Ed Clark and trustees Susan Rockmore and Dan Rey — called “Voorheesville, New York: A Sketch of the Beginnings of a Nineteenth Century Railroad Town.” It reads like the Sunday paper.

And that book came about because, when I was interviewing the likes of Jane Blessing and Sam Youmans and Madelon Pound for the Bender project, I was often told I should have spoken to so-and-so but, when I asked where so-and-so was, I was told, oh, he died, which happened so often I came to the conclusion that, if I did not start working on the history of Voorheesville that very moment, much of its past would be lost to death.

Thus, once I finished with Bender, I started on Voorheesville. The tome is now in its fourth printing and receives high marks. I can describe its structure inside out.

When I took over as village historian, each year the mayor and board of trustees provided the office of the historian with a budget to purchase artifacts and the like related to the municipality’s history.

Now, with a few dollars in my saddle bag, I went to visit George and told him I wanted to buy the Hendrick book.

He hesitated saying, “I don’t think so; that book is worth a lot of money.”

On the spot I said, “I agree, the book is important, George; therefore I will give you $200 for it.” He came back with a sharp No.

I thought for a second then said, “OK, how about $300?” Again, a firm No and I figured that was the end of my relationship with a treasure from our commonwealth.

I had not seen George for years and forgot all about the book until late one winter afternoon on the way back from the post office, in the face of a wind-driven sleet, I saw George pumping gas at the Stewart’s Shop located diagonally across from the village hall in Voorheesville.

I asked how he was doing because his wife, Shirley, had died in November 1993. He said he was faring well enough and I offered my condolences.

And then, turning to go, I said, “Oh, George, what about the book!”

With no hesitation, he came back with another No, saying something like, “Someday the book will find its rightful owner.”

So, for all intents and purposes, I closed my book on the book and the possibility of our community ever having an important piece of its history.

Then, seven or eight years later, while driving on Route 9H to Poughkeepsie to catch the Metro North to New York City, my bladder started whining for help.

I recalled there was a large brick barn near the Kinderhook exit that had been turned into an antiques emporium with many stalls (dolls, glass, old tools, postcards, etc.).

I pulled into the barn lot and inside hurriedly approached an elderly woman at the check-out desk, and asked if they had a restroom I might use.

She said shortly, “We have no restroom here.”

A bit miffed, I shot back, “You mean to say no one working here ever has to go to the bathroom during the workday?”

She shot back, annoyed, “We have no bathroom.”

I said, “Well, do you have a bathroom for customers?” figuring I would buy some trifle and quickly end my agony.

With emphasis: “We have no bathroom.”

As I headed to the door in search of relief, my eye caught some tables to the left with books spread across the top and, because I have a bumper sticker implanted in my brain that says I BREAK FOR BOOKS, I went over and quickly assayed the layout and, as I turned to go, my eye — mirabile dictu — saw it! The book! “Relations, Recollections and of the Hendrick Family!” My source for Charlie Bender!

I picked it up in radical disbelief, especially when I saw a price card sticking out from the top of its pages that read: $60.

More than slightly shaken, I took the blue hard-board-bound copy and hurried to the elderly woman at check-out, paid her the $60 fast to take my leave but did slip in that I had been looking for a copy of the book for some time.

She said, “Well, you’re lucky; the stall belonged to a man who died recently named George Matuszek, from New Scotland, we’re trying to get his family to come and get the books.”

I thought: George was right, the rightful person did come along to take possession of a work of art meant for him and for his community, and then whispered a Catullan-like prayer, “Ave atque vale, amice Georgi.”

From that day until today, the book has been part of the archives of the village of Voorheesville, which are now housed, and being catalogued, in the Voorheesville Public Library.

And for those interested in the outcome of my strained bladder that day, well, the back wall of the barn shared the joy of me finding a long-lost treasure as it got rained upon super-fluous-ly.

That is my story of provenance as I keep seeking to know if New Scotland’s citizens of today — which includes Voorheesville of course — care at all about the shoulders of the giants they now stand on.

No hay más que hablar.

In a speech given to the House of Commons in 1948, Winston Churchill issued — the hot breath of war still blowing on the neck of Europe — a warning to the world: “Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.”

The phrase was not his; he borrowed it from the great Spanish-American philosopher and poet George Santayana who in his “The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress” proclaimed: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

“Progress,” Santayana said, “far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness,” that is, on a society having an accumulated body of knowledge derived from capturing the truth of what appears before the eyes.

He added that, when a society fails to retain the lessons of the past, “infancy is perpetual” and making no “improvement,” it moves a step closer to its demise, certainly to a disfigurement beyond recognition.

In my own way, I say the same thing in my most recent work “Veni, Vidi, Trucidavi: Caesar the Killer; A Man Who Destroyed Nations So He Might Be King.”

The title is a play on Caesar’s famous “Veni, Vidi, Vici”: “I Came I Saw I Conquered.”

Mine says, “I Came I Saw I Slaughtered,” referring to the pall of death caused by the vast military machine Caesar produced to mow down the native tribes of Gaul during his nine years as governor there.

The premise of “Veni, Vidi, Trucidavi” is that a grand jury is convened to determine whether Caesar committed genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes or maybe them all, to satisfy an innate drive to become the king of Rome.

Every reader of the book is asked to be a member of the grand jury and — after listening to the evidence the prosecutor presents — moi — to determine what crimes Caesar should be convicted of.

The blurb on the back was offered by the esteemed classicist James O’Donnell, who wrote: “Caesar was stabbed twenty-three times in the most dramatic and spectacular assassination in all recorded history. Dennis Sullivan makes it twenty-four, with a compelling account of the man and his many crimes. He brings Caesar to life as his fans and apologists have never been able to do. Learning to do justice to the great villains of history can help us cast a cooler eye on the malevolent leaders who have swarmed onto the world stage in our time.”

Modern historians have called attention to the many similarities between the Republic of Rome and the Republic of the United States, often intimating that the history of Rome toward the end of the Republic’s life, has lessons for the United States if it wishes to keep its democratic boat afloat.

Caesar hammered the last nail in the coffin of Rome’s republican government by putting his own needs above the city’s collective identity — a way of life Roman citizens cherished since 509 B.C. when it ousted its last king.

Many writers and historians have called attention to the desire of the current president of the United States to be a king as he keeps hammering nails into the coffin of American democracy.

In her Jan. 9, 2025 article in The New Yorker called “King Donald and the Presidents at the National Cathedral,” Susan Glasser refers to the five former chief executives of the United States who were present at the funeral service of President Jimmy Carter, four of whom she calls “president,” the other a king.

How amazing she says that, “at a pre-inaugural press conference as if … he had been elected not President but Emperor, [he spoke about] how he wanted to annex Canada, take over the Panama Canal, and force the sale of Greenland to the U.S. — and he would not rule out the use of coercion against the U.S.’s allies in order to do so.”

Such goals are achievable today because a lobotomized America has lost her memory “spread out against the sky,” to give a nod to T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” “like a patient etherized upon a table.”

The republican Rome of Caesar was similarly anesthetized having forgotten the lessons Lucius Cornelius Sulla sent, the man who started Rome’s first civil war, who set himself up as dictator for life, and the first citizen to seize the presidency of the republic by force.

What is worrisome to many Americans now is that nominees for upcoming federal cabinet jobs admit there is an “enemies list” while the man nominated to head the FBI, Kash Patel, says he will “come after” journalists and all enemies like them.

Outgoing president, Joe Biden, took the retribution threats seriously, so that on Monday, Jan. 20 — his last day in office — he issued preemptive pardons to those threatened with social extinction: Dr. Anthony Fauci, retired Gen. Mark Milley, and the lawmakers who served on the January 6th Committee.

On Nov. 2, in 82 B.C., the day after Sulla took full control of Rome (Italy) by force, he went to the Senate and asked the lawmakers to sanction his proscription list, which entailed killing or banishing citizens who disagreed with the way he exercised power.

When the Senate rejected his proposal, the dictator went to Rome’s popular assembly — essentially our House of Representatives — and there got the OK to proceed with the slaughter.

Sulla began by publicizing a list of 80 of the highest-ranking public officials — the Liz Cheneys, Adam Schiffs, and Adam Kinzingers of the day — whom he wanted dead and, a day or two later, came out with a second list of 440 more names.

The streets of Rome were already damp with blood because right after he took over, Sulla ordered the slaughter of 6,000 Samnite prisoners, the cries of their bodies being hacked apart within earshot of the gathered Senate, terrifying everyone. Sulla said the hub-bub was “nothing more than the screaming of a few criminals paying the just penalty for their crimes.”

The property of anyone proscribed was confiscated and put up for sale, the same for his descendants who lost their civil rights and were then banished from the country.

Every Roman knew who was on the death list because the names had been prominently displayed in the Forum. It signaled the beginning of a bounty hunter’s paradise.

That is: Everyone who killed one of the proscribed received a large monetary reward and was immune from prosecution; those who informed on a black-lister also received a gift, and slaves who “took out” someone were freed. Monies to pay for the bloodbath came from the aerarium, the public treasury, thereby making every Roman citizen an accessory to the fact.

In order for a “hit man” to receive compensation, he had to produce the head of the demised; indeed, Sulla had groups of heads paraded through the streets raised high on pikes, the artifacts later put on display at the communal speakers’ platform, the Rostrum; there was to be no burial for the traitors and no public mourning was allowed; heads and bodies were left for the birds of the air.

The French historian François Hinard remarks, in his classic work on the subject “Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine” (1985 )— the detail he offers is chilling — that the monies changing hands with all the killing exceeded two million sesterces.

The insatiate pig in the crowd, Marcus Licinius Crassus, bought so many of the confiscated properties that he was on his way to becoming the richest man in Rome, worth, in today’s market, well over two-hundred-million dollars.

Sulla said the extermination was his response to what the other party had done to him and his: the Republican and Democratic factions of ancient Rome having been reduced to dealing with ideological differences through extermination.

In his monologue on the television program “Saturday Night Live” for Jan. 18, stand-up comedian Dave Chappelle said he hoped the incoming president would “do better [than he did the last] time” and asked all avowed Sulla-like retributivists in his camp to “not forget your humanity … please have empathy for displaced people, whether they're in the Palisades or Palestine” or must every American be looking over his shoulder like Satchel Paige?

Quo vadis, America? Quo vadis?