Enterprise file photo — Marcello Iaia

“Self-discipline” was defined by William Bennett as, “controlling our tempers, or our appetites, or our inclinations to sit all day in front of the television.” Modern Berne-Knox-Westerlo students last year got a taste of earlier school discipline when they visited a one-room schoolhouse in Knox.

In his memoirs, Ben Franklin wrote, “There was never a truly great man that was not at the same time truly virtuous.” I’m not sure who “The Prophet of Tolerance” would put in the category of “great men” today, but I am sure he would not call them virtuous because the words “virtue” and “virtuous” have all but disappeared from our vocabulary.

Even “habit,” as a disposition of the soul — and long associated with virtue — is non courant and might explain in part a growing concern about the loss of the “virtue” of self-discipline.

Years ago, William Bennett, who served as the nation’s first drug czar under George Bush (the 41st president), was bothered by this erosion in cultural values and took it upon himself to assemble a more than 800-page tome called “The Book of Virtues: A Treasury of Great Moral Stories.” This “‘how to’ book for moral literacy” is filled with poems and stories Bennett hoped kids would read and “achieve at least a minimum level of moral literacy” through the development of “good habits.”

He showcased 10 virtues among which were “compassion,” “courage,” “honesty,” “loyalty,” and “self-discipline” — the last of which he begins the book with — the “controlling our tempers, or our appetites, or our inclinations to sit all day in front of the television.”

I went back and looked at what Bennett said about discipline because there were several articles in the newspapers recently in which discipline took center stage.

On March 14, Paul Sperry of The Post wrote a piece called “How liberal discipline policies are making schools less safe.” Sperry said, “New York public-school students caught stealing, doing drugs or even attacking someone can avoid suspension under new ‘progressive’ discipline rules adopted this month.” Id est: The inmates are running the asylum.

Such a take on self-control is not new. In his column a while back, psychiatrist Greg Smith bemoaned the erosion of discipline at home and school alike.

In school, he said, teachers were “hamstrung” and at home, “Parents do not feel that they make the rules anymore. There can be no house rules. There can be no punishments, behavioral or corporal or otherwise, because Little Johnny has the Department of Social Services on speed dial on his $600 iPhone and will call them if his parents lift a finger to keep order in their own home.”

A cynical assessment from a psychiatrist and a pretty paranoid kid, unless of course he knew something we didn’t.

But Bennett comes to the rescue with a solution for how to handle such unrestrained beings using the words of Hilaire Belloc’s poem “Rebecca.” Belloc says there was “a wealthy banker's little daughter,” Rebecca, who was “aggravating” and "rude and wild" and made "furious sport" by “slamming doors” in the house startling the h-e-double-hockey-sticks out of uncle Jacob.

And because this little darling did not seem amenable to feedback, shall we say, someone in the family took it upon himself — or herself (it does not say who) — to set a heavy marble bust atop the door so that, when Rebecca blew through next and clapped the portal shut, the bust came down and killed her on the spot.

Rebecca’s good points were mentioned at the funeral but a warning was sent to those situated similarly to "The Dreadful End of One/Who goes and slams the Door for Fun." Through the words of Belloc, the drug czar’s riposte of neutralization makes boot camp seem like vacationing in Rome.

Then there was the article in The Times on March 11 about the Arkansas senator, Tom Cotton, who was responsible for “the” letter to the leaders of Iran urging them to not make a deal with the Obama Administration on nuclear arms.

Cotton’s fans and detractors both said he was highly “disciplined.” But retired Army General Paul D. Eaton, a senior advisor to the National Security Network, said, “The idea of engaging directly with foreign entities on foreign policy is frankly a gross breach of discipline.”

What! Is there a good discipline and a bad discipline? Can one stay in bounds in some arenas and then transgress boundaries in others? Such a division would seem antithetical to self-control.

To prevent the transgression of boundaries and the harm it creates — which might include tempers flaring and appetites spilling out onto the floor of the world — for ages monks “took the discipline,” that is, used a cattail whip of knotted cords (itself called a discipline) to lash themselves across the back during prayer. Pope John Paul II was said to have taken the discipline and even brought his whipping belt on vacation.

But we know externally imposed discipline and neurotic attempts at controlling the self work intermittently and have no legs. E.g.: We’re speeding along, we see a cop, we slow down, a half-mile down the road we ramp it back to 80 — without a wisp of guilt. So much for the threat of boot camp.

Years ago, I was taken with the great classics teacher and philosopher Norman Brown’s famous Phi Beta Kappa speech at Columbia University in 1960 — another was Emerson’s at Harvard in 1837 — where he spoke about how to achieve a lasting discipline, far afield of any marble bust snapping the neck of a child across a door jamb.

Brown said the answer is enthusiasm and he explained to the assembled that the word comes from the Greek “entheos,” which means “god in us,” so that “the eyes of the spirit...become one with the eyes of the body, and god [is] in us, not outside.”

Who needs external control if you’re on fire with purpose and dedicated to actions that support life and can see their joyful effects?

Enthusiasm excludes high performing, automaton, grade-mongering students in schools and rigid automatons in the workplace. Research shows kids in that boat tend to be superficial in their thinking, less creative, and let go of what they learned when the pay-off ends (when the cop is out of sight). It’s doubtful whether such souls will ever become one of Franklin’s virtuous few.

And, if you’ll recall, the aforementioned Mr. Bennett was a “preferred customer” big-stakes gambler at Atlantic City and Vegas and reportedly lost more than $8 million on Lady Luck’s $500-a-pull-slots and other games of fate.

When Bennett was brought to task for what seemed a contradiction in the words v. deeds department of self-discipline, his ideological ally, William Kristol, editor of The Weekly Standard, said that it was a matter between Mr. Bennett, his wife, and his accountant.

I thought it was an issue of controlling appetites. Would anyone on fire for life give even a passing glance to the capricious lure of Fortuna? Enthusiasm would never stand for it.

— From the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers

Howard Stansbury, a civil engineer, was a captain. His only known image is from a carte d’visite; on the back is a handwritten note, attributing his 1863 death “to disease contracted in the Rocky Mountains.” He was born in New York City on Feb. 8, 1806.

In 1852, the United States Senate published the findings of Captain Howard Stansbury’s 1849-1850 expedition to the Great Salt Lake. The report was called “Exploration and Survey of the Valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah: Including a Reconnaissance of a New Route Through the Rocky Mountains.”

Stansbury, an officer in the Corps of Topographical Engineers, had been assigned by the Senate to travel from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to the Great Salt Lake to scout out emigration trails, especially locations that might benefit the coming continental railroad.

The report is comprised of entries of what Stansbury and his team saw and did each day. Scientists were thrilled with his takes on new flora and fauna and the animals they came across, as well as the captain’s account of the Mormon community with which he lived one winter under the direction of Brigham Young.

Ethicists were thrilled with what Stansbury had to say on May 30, 1850 while walking along the shores of Gunnison’s Island situated in the middle of the lake, a key breeding ground for the American white pelican.

Stansbury was admiring the flood of pelicans along the shores of “the bold, clear, and beautifully translucent water” when he came across “a venerable looking old pelican, very large and fat,” which allowed Stansbury to approach him “without attempting to escape.”

More striking was the pelican’s “apparent tameness [and when] we examined him more closely,” Stansbury says, “[we] found that it was owing to his being entirely blind, for he proved to be very pugnacious, snapping freely, but vaguely, on each side, in search of his enemies, whom he could hear but could not see.”

And because the pelican “was totally helpless,” Stansbury knew he “subsisted on the charity of his neighbors, and his sleek and comfortable condition showed, that like beggars in more civilized communities, he had ‘fared sumptuously every day.’”

Pelicans are piscivorous, fish-eaters, and, since the salinity of the Great Salt Lake allows few fish to thrive, adult pelicans on Gunnison travel more than 30 miles one way to get food for their young — and their blind “comrade.”

An admiring Lewis Henry Morgan included Stansbury’s story in his classic “The American Beaver,” published in 1868, but perhaps more tantalizing is that Mr. Charles Darwin recorded that act of empathy in “The Descent of Man” three years later.

Though acts of mutual aid do not fit nicely with “survival of the fittest,” Darwin avers in “The Descent of Man,” “I have myself seen a dog, who never passed a cat who lay sick in a basket, and was a great friend of his, without giving her a few licks with his tongue, the surest sign of kind feeling in a dog.”

He offers examples of other dogs, baboons, elephants, cattle, and birds acting toward their comrades with a “moral instinct” that can only be construed as empathy.

The scientist and philosopher-anarchist Peter Kropotkin knew of the pelican story and referenced it in “Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution,” published in 1902. In the first two chapters, Kropotkin offers a host of examples of animals coming to the aid of each other when needed.

And, in an oft-cited lab experiment dealing with animal empathy — written up in the “American Journal of Psychiatry” in 1964 — Jules Masserman and his team at Northwestern University tested to see if monkeys would give one up for the Gipper, as it were, when called upon.

The experiment allowed rhesus monkeys to pull a chain to access food but, when they did, a monkey next to them was zapped with an electric shock. After a time, the monkeys refused to pull the chain — maybe Masserman should have pulled the plug at this point — one monkey not eating for 12 days, risking starvation to avoid paining another.

On Gunnison, what went on in the pelicans’ minds such that they “felt” compelled to bring fish for a useless comrade? Or what makes the famed meerkat risk death when serving as a lookout for his foraging clan? Can we attribute such acts to protoplasm alone?

Several years ago, Voorheesville veterinarian Holly Cheever told me a story of her earliest days of practice with dairy farmers in upstate New York.

She said she got a call one day from a farmer complaining that one of his brown Swiss cows — who just delivered a calf on pasture (her fifth for the farmer) — when brought onto the milking line, was found to have a completely dry udder. It could not have been the calf because her calf had been taken right after birth — standard practice.

The dry-udder situation continued for days when the bottom line says a new mother should produce one hundred pounds (12.5 gallons) of milk a day. The farmer was at his wit’s end.

Cheever reiterated last week that the mother was healthy, she was following the routine of the other cows — out to and back from pasture — but still no milk.

Finally, on the 11th day, the hapless farmer followed the cow and saw her head into a woods at the edge of the pasture where, mirabile visu, he saw a calf waiting for his mother whom she fed at her heart’s delight. She had given birth to twins!

If she had hid both calves, the farmer would have known right away; all things being equal, a pregnant cow would not go out to pasture and come back with nothing.

I think, as Chever does, that this cow had a maternal sense of justice. She had already given the farmer five babies, all taken right after birth. Now that she birthed two at once, she figured: One for him, one for me! She tipped the scales of justice her way.

Cheever said, “All I know is this: There is a lot more going on behind those beautiful eyes than we humans have ever given them credit for, and, as a mother who was able to nurse all four of my babies and did not have to suffer the agonies of losing my beloved offspring, I feel her pain.”

I know about the Animal Protection Federation and the recent efforts of Albany County District Attorney David Soares enabling authorities to better respond to, and prevent, animal abuse in the county.

But I remain stunned as to how folk can harm our compatriots who tell us in a million different ways where we came from and how we might better ourselves by offering aid to every blind pelican that comes our way.

I’m sure most people, when asked to provide a list of emotions they experience in a given month, would not include “schadenfreude” even though it rears its head often enough.

Coming from the German “schaden,” which means harm, and “freude,” meaning joy, the experience is one of feeling pleasure at the misfortune of another.

It’s a strange emotion to be sure because we usually associate joy with a pleasant outcome whereas schadenfreude is pleasure derived from another’s ill.

And the experience is universal. William James in “Principles of Psychology” says, “There is something in the misfortunes of our very friends that does not altogether displease us; [even] an apostle of peace will feel a certain vicious thrill run through him, and enjoy a vicarious brutality, as he turns to the column in his newspaper at the top of which 'Shocking Atrocity' stands printed in large capitals.”

Indeed researchers who seek to quantify its presence in our lives say schadenfreude is on the rise. In “The Joy of Pain: Schadenfreuse and the Dark Side of Human Nature,” Richard Smith says he looked at the number of times “schadenfreude” appeared in the English language from 1800 to 2008. In modern times, he says, from the 1980s on, schadenfreude as concept and “practice” has achieved a greater share of our emotional landscape.

I’m inclined to think it’s because we’ve become a more punitive and cynical society, maybe even more sadistic, and schadenfreude is one of the manifestations of that callousness — though schadenfreude is not in the same ballpark as sadism (or even gloating), which are more actively aggressive in nature.

Because schadenfruede is etymologically German, for years critics characterized it as a peculiarly German phenomenon, especially during World War II! But, when we examine the spectrum of world cultures, we see that every culture has its own word or combination of words to denote this emotion or some approximation of it.

The French have their “joie maligne,” Hebrew has “simcha-la-ed,” and ancient Greek has “epichairekakia,” which ancient as well as modern scholars say is a distant relative of greed, avarice, and envy.

In Japanese, there’s “meshiuma,” which means, “Food tastes good that comes from the misfortune of others.” The writer Gore Vidal once remarked, “Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little.” The converse would be, “Every time a friend fails, I am more alive” and the double converse, “I derive pleasure from the misfortune of others.”

For those unfamiliar with the word (I will not say the experience), an example might be helpful at this point.

We are driving along our favorite county road, staying well beneath the 30-mile-per-hour speed limit because the road is highly patrolled. All of a sudden, a large SUV appears in the rearview mirror with a young kid at the wheel and he’s up our bumper.

Staying our course, we see the “kid” begin to wave his arms in what seems to be gestures of anger; he then pulls out over the double yellow line and guns it past us. As his passenger window nears ours, he looks down at us with derision and double-guns it up the hill and out of sight.

A few moments later, as we near the hill, we see his car pulled over and a cop writing him a ticket. If we feel a certain satisfaction at this point and think something like, “He got what he deserved,” or, “Justice triumphed,” or, “There is a God,” we are in the schadenfreude business.

When Martha Stewart was indicted in 2001, the United States experienced a kind of national schadenfreude. People felt that the person who had dictated personal and social tastes for years finally got her comeuppance.

There is some debate over whether the shadenfroh’s delight comes from the bodily pleasure produced or seeing society’s fabric saved. In other words, was justice done to the nervous system or to the collective? And there is strong evidence that shows when the experienced misfortune is great, schadenfreude all but disappears and a hybrid form of empathy kicks in.

Understandably schadenfreude has been linked to envy because when we envy another’s possessions or achievements, we engage in an internal (and often subtle) trash-talk dialogue, subconsciously trying to improve our own lot. People pay big money to therapists for years to understand and get out from beneath such a complex.

The irony is that people will talk about schadenfreude experiences openly whereas they are far more reluctant to speak about what they envy because envy is an open admission of inferiority.

Of course the moral implications of schadenfreude have not gone unnoticed. In Spanish there is a saying: Gozarse en el mal ajeno, no es de hombre buen (“A man who rejoices in the misfortunes of others is not a good man”). Or should we say is a person who has not reached emotional maturity?

We do know that when schadenfreude is primed with emotional steroids, the frequency and intensity of its presence leads to the destruction of relationships. When I first came upon schadenfreude years ago, I immediately thought of the great psychoanalyst Karen Horney’s concept of “vindictive triumph,” which she saw alive in her patients saddled with neurosis. Vindictive triumph might be viewed as schadenfreude when it becomes a structural part of our identity and one justified by a more highly toxic logic.

In “Neurosis and Human Growth,” Horney says the drive to vindictively overcome others grows out of “impulses to frustrate, outwit, or defeat [them] . . . because the motivating force stems from impulses to take revenge for humiliations suffered in childhood.”

Often enough, this chronic illness might be accompanied by headaches, stomachaches, fatigue, and insomnia because the drive to see others get their “due” is relentlessly churned up in the subconscious.

If vindictive triumph is indeed a compensatory mechanism, and schadenfreude and vindictive triumph are in fact manifesting themselves more frequently in our culture, as research suggests, what are we compensating for? Why has the need to triumph vindictively moved center stage? Why the need for such an array of trophies?

Heavy stuff indeed, but, as the United States continues to undergo its current identity crisis, understanding what drives people to increasingly take joy in the misfortune of others will enable us to forge a less aggressive future self. Maybe that’s what the great American poet Allen Ginsberg was alluding to when he said, “Candor disarms paranoia.”

La Grande Chartreuse is the head monastery of the Carthusian order and is situated in the Chartreuse Mountains north of Grenoble, France. The order, founded in 1084 by St. Bruno, follows rules called the Statutes. Visitors are not permitted at the monastery and motor vehicles are prohibited on nearby roads. Philip Gröning’s movie about the monastery, Into Great Silence, is available for loan at both the Voorheesville and Guilderland public libraries.

Nearly 50 years ago, I made a rule never to recommend movies, restaurants, and vacation spots to anyone save a few intimates whose number today I gladly count on half a hand.

And though I firmly believe rules are made to be kept, I’d like to call attention to Philip Gröning’s 2005 documentary on the Carthusian monks at La Grande Chartreuse, the Carthusian motherhouse in the valley of the Alps of Dauphine north of Grenoble, France.

The highly critically acclaimed film is called Into Great Silence and its tourdeforcity is a human magnet.

At a period when Gröning was obsessed with trying to understand “time,” he wrote to the superior of the 4,268-foot high Carthusian charterer house seeking permission to record the life of the monks. The superior wrote back saying they wanted to think about it. Sixteen years later, Gröning received a reply saying they were ready, if he still had interest.

He did and arrived at the monastery in mid-March 2002 as a team of one: the film’s director, producer, cameraman, soundman, grip, and whoever else was needed to get the job done. To fully grasp the depth of silence the monks lived in, Gröning decided to live with them and follow their highly structured horarium.

And though the monks chipped in to help Gröning move his equipment up mountainous slopes surrounding the monastery when needed, the director was solely responsible for lugging his tools.

One day, while shooting along a steep ridge, he fell 20 feet and found himself spread out on a slab of stone thinking his day had come. It hadn’t, and after a bit he was back shooting the 120 hours of film that served as the vein from which he mined the 162 minutes that comprise Into Great Silence.

The editing was harrowing for Gröning; it took him more than two-and-a-half years to find a proper narrative. He could not find the glue to hold things together.

Those familiar with Roman Catholic religious orders know the Carthusians are the strictest of all. The monks live in near-total silence, spending most of the day in their cells (warmed by a tin-can-shaped wood-fired stove) and in a walled-in garden.

In these spaces, the monks meditate, pray the liturgy of hours, read, write, and eat alone. Each monk washes his own clothes, does his own dishes, splits his own wood (it gets cold there), and works in the garden for exercise and cultivating plants.

The monks are also assigned communal chores to support the upkeep of the house. For some, this means making the green-colored Chartreuse liquor for which the monks have been famous for centuries.

Some have said the highly structured schedule leaves no “free time” for the monks, but the monks say their whole life is free.

They do leave their cells to chant in the chapel and celebrate Mass. On Sundays, they eat together in silence as one of the monks reads aloud and once a week they take a walk in the woods for hours where they converse about “edifying” things. Gröning caught the monks sliding down the snowy slope of a hill, yelping like kids on holiday, using their shoes as sleds.

Twice a year, the monks may receive a daylong visit from family members, and the silent grounds of the monastery grow abuzz with the chatter of kids and adults alike. Though not of this world, the Carthusians recognize the importance of the human feelings and the connections the monks had (have) with the families they grew up in.

They sleep no longer than three hours or so at a time. To bed at eight, they’re up past eleven praying and singing psalms, then back to sleep for three hours, and up again to celebrate more lectio divina. Those who persevere after the novitiate spend an average of 65 years in the monastery doing the same thing every day of every year, with no place to go and no apparent goals.

Gröning beautifully captured their spirit on film and I recommend it because it does deal with “time” in that it shows human beings who treat each moment of life as if it were the totality of that life and who find happiness in such gestures of gratitude. If you watch the film, it will blast smugness out of every bone.

When I speak to Roman Catholics about the film, more than a few claim the movie is a Roman Catholic venture because the Carthusians are a Roman Catholic order. And I tell them they are reading it wrong because the movie is about human beings who fully appreciate what life presents to them each moment of the day, and that that human possibility is not sectarian but belongs to everyone.

I saw the movie at the Spectrum 8 in the city of Albany when it first came out and it knocked my socks off. I was back three days later for a second sock-knocking. I’ve watched it on DVD after that but judiciously because it is such a workout.

The writer Adair Lara said that, when she was growing up, her mother “used to wash our clothes in a wringer washer and then hang them on the clothesline outside. As she pinned up each garment, she said, she thought about the child it belonged to. She never wanted a dryer, even after we could afford one, because it would steal this from her, this quiet contemplation.”

That woman understood the great silence of La Grande Chartreuse, aware of the precious gift that every moment is, realizing that that gift could disappear in the blink of an eye.

If you decide to watch the film, pour yourself a beer or cup of tea, or whatever you like to have at the movies, sit back, and give yourself over to the life ahead without interruption.

You will be transported into another world of time and space and perhaps like me return transformed, an appreciator of the soil in which great silence is born.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, who lived from 1793 to 1864, has long been heralded as Guilderland’s most prominent son, in these pages and elsewhere.

In his local history classic Old Hellebergh, published in 1936, the late Guilderland town historian, Arthur Gregg, said, “There has never been in the long category of soldiers, patriots, statesmen, manufacturers, educators, and jurists, born and reared in sight of the ‘Clear Mountain,’ [the Helderbergs] one with more fame than the pioneer . . . Henry Rowe Schoolcraft.”

A Renaissant-like omnivore of human experience, Schoolcraft was a glass manufacturer early in life, then a mineralogist, then a geologist, explorer, ethnologist, poet, editor, and for 19 years, from 1822 to 1841, served as United States Indian Agent headquartered at the frontier posts of Sault Ste. Marie and Mackinac Island, assigned the tribes of northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.

To many folklorists, Schoolcraft is considered the first “scholar” to amass and publish a body of Indian folklore and deserves to be called the father of American folklore. When he arrived in Michigan, he lived with the family of John Johnston, an Irish fur trader who married the daughter of a prominent Ojibwa war chief and civil leader from northern Wisconsin.

Schoolcraft married Johnston’s daughter, Jane, who provided him with a host of Chippewa legends. His mother-in-law gained access for him to stories from “the greatest storyteller of the tribe” and to ceremonies open only to tribe members.

Schoolcraft’s ethnological findings were published in many volumes, the magnum opus of which is his six-volume folio-size Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, published between 1851 and 1857, and costing $150,000.

As editor and writer, Schoolcraft, in 1826 and 1827, produced a much-sought-after weekly journal called the Literary Voyager. The 15 issues constitute the first magazine produced in Michigan and one of the first to appear in the frontier west.

Schoolcraft’s accomplishments have not gone unnoticed. In the Midwest, particularly Michigan, the Schoolcraft name is ubiquitous. A Michigan County is named after him, a town, a village, river, lake, island, highway, ship, park, and even the culinary arts Schoolcraft College in Garden City, Michigan has a food court called Henry’s.

As a person with an abiding interest in local history, I paid due attention to Schoolcraft over the years, particularly his relationship with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow whose epic poem, “The Song of Hiawatha,” was based on information Schoolcraft published.

But what enthralled me most about Schoolcraft was a touching one-page story I came upon two years ago when I was looking at Oneóta or Characteristics of the Red Race of America, published in 1847. It is called “Chant to the Fire-Fly.”

Schoolcraft relates that on hot summer evenings before bedtime Chippewa children would gather in front of their parents’ lodges and amuse themselves by singing chants and dancing about.

One spring evening, he says, while walking along St. Mary’s River, the evening air “sparkling with the phosphorescent light of the fire-fly,” he heard the Indian children singing a song to the firefly. He was so taken with the chant he jotted it down in the original “Odjibwa Algonquin [sic].”

Below the text, Schoolcraft offered two translations of the chant — one “literal,” the other “literary” — of a song he says that was accompanied by “the wild improvisations of [the] children in a merry mood.”

I will not give the Ojibwa — you can find it on page 61 of Schoolcraft’s Oneóta — but I will provide Schoolcraft’s literal translation. After I read the poem several times, I could not escape its charms. I envied Schoolcraft that evening when he first heard the children sing. This is his translation:

Flitting-white-fire-insect!

Waving white-fire-bug!

Give me light before I go to bed!

Give me light before I go to sleep!

Come little dancing white-fire-bug!

Come little flitting-white-fire-beast!

Light me with your bright white-flame-instrument—

Your little candle.

I was so taken with this text that I wrote two poems about the firefly and started looking deeper into the story but the more I did the more I smelled something rotting in Denmark.

That is, I found a chorus of folklorists, linguistic anthropologists, ethnopoeticists [mine], and those of that ilk, taking Schoolcraft to task for being a “textmaker” rather than a scientist dedicated to taking down the Indian world as it presented itself to him.

Schoolcraft wanted to produce something “literary” (marketable), and to achieve that, he engaged in mediating between what the Indians said and what a projected readership might accept from the “savage.”

Schoolcraft says he began to weed out “vulgarisms,” he “restored” the simplicity of style, he broke legends “in two,” “cut [stories] short,” and lop[ped] off excrescences.”

In the introduction to The Myth of Hiawatha and Other Oral Legends, published in 1856, he said the legends had been “carefully translated, written, and rewritten, to obtain their true spirit and meaning, expunging passages, where it was necessary to avoid tediousness of narration, triviality of circumstance, tautologies, gross incongruities, and vulgarities.” In other words, what did not fit his aesthetic and religious views of reality, went.

While giving credit to Schoolcraft for his pioneering work, the early 20th-Century folklorist Stith Thompson noted, “Ultimately, the scientific value of his work is marred by the manner in which he reshaped the stories to suit his own literary taste. Several of his tales are distorted almost beyond recognition.”

This is not an imposition of postcolonial standards on Schoolcraft’s doings. As Richard Bremer points out in his full-length biography of Schoolcraft, Indian Agent and Wilderness Scholar, even Francis Parkman told Schoolcraft to stick to the facts.

Though he often exhibited paternalist sympathies with the Indians, Schoolcraft signed treaties as the Indian Commissioner for the United States that displaced the Michigan Indian. The Treaty of Washington in 1836, concluded and signed by Henry Schoolcraft and several representatives of the Native American nations, saw approximately 13,837,207 acres (roughly 37 percent of the current State of Michigan) ceded to the People of the United States.

I went over to Willow Street the other day to visit Henry’s house, waiting in the cold outside, thinking he might come out. I have many questions for Henry Rowe Schoolcraft.

Peter Henner, a lawyer from Clarksville, wrote an award-winning chess column for The Altamont Enterprise, "Chess: The Last Frontier of the Mind," for four years, retiring from the column in the fall of 2014 to resume his law practice on his own terms. His columns are archived here.

In the winter of 2015, Dennis Sullivan, a scholar and historian from Voorheesville, began his column "Field Notes."

Crossword puzzle lovers may have wondered about the frequent clue “Russian chess champion” (three letters). The answer is “Tal,” as in Mikhail Tal, who died on June 28, 1992. The “Magician of Riga,” as he was known, Tal became the eighth World Champion in 1960, at the age of 23.

The Soviet-Latvian Grandmaster, who had been terrorizing the chess world for the previous five years, particularly the relatively staid Soviet players, with his unorthodox style of play, was, at the time, the youngest player to win the world championship.

Tal was known as a brilliant attacker, a creative genius, who played intuitively and unpredictably. Today, with modern computers, we know that many of his speculative sacrifices were unsound and should have lost.

Tal himself said “There are two types of sacrifices: correct ones, and mine.”

However, it was not easy, even for the world’s best players, to refute these sacrifices over the board, and contemporary analysts usually were unable to show why or how Tal could have been defeated.

His style was a challenge to the Soviet school, exemplified by Mikhail Botvinnik, which preferred systematic logical chess, buttressed by hard work and study. Botvinnik, who, with one interruption, had been Champion since 1948, prepared carefully and methodically for the 1960 match.

Tal, in contrast, simply played a tournament in his hometown. Tal decisively won the match by a score of 12 ½ - 8 ½.

However, the Fédération internationale des échecs rules at the time permitted a rematch for a defeated Champion, which Botvinnik won, 13-8.

In the second match, Botvinnik, once again carefully preparing for the match, deliberately played for closed positions, leading to positional struggles and endgames, and avoiding the sharp tactical play that Tal loved.

During the rematch, Tal continued to play his favorite Nimzo-Indian Defense and the aggressive advance variation of the Caro-Kann, even as it became clear that these openings were not working for him. It was not until five years after the match that Tal, playing White against Botvinnik, abandoned the advance variation in favor of the more common Panov variation and won easily.

Tal had a great career, winning the USSR championship six times between 1957 and 1978 (when that tournament was probably the strongest tournament in the world), established a record in 1973 - 74 by playing 95 tournament games without a loss (46 wins and 49 draws), and tied with Karpov for first in the 1979 Montréal “Tournament of Stars.”

Although he continued to compete in world championship cycles, he never again played a match for the world championship. However, at the age of 51, he won the World Blitz Championship ahead of then world Champion Kasparov.

Tal died young: He suffered from serious health problems all his life, complicated by chain-smoking, excessive drinking, and partying. His wife, Salli Landau (they were married from 1959-1970), who wrote a biography of Tal, noted that, while some people thought he might have lived longer by taking better care of himself, if he had done so, he would not have been Tal.

She also commented that Tal “was so ill equipped for living… When he traveled to a tournament, he could even fact is on suitcase… He didn’t even know how to turn on the gas for cooking…Of course if he had made some effort, he could have learned all of this. But it was all boring to him. He just didn’t need to.”

In the spring of 1992, shortly before he died, Tal escaped from his hospital room to play in a blitz tournament. The following game, played against Kasparov, is generally regarded as his last game.

Tal –Kasparov 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. Bb5+ Nd7 4. d4 Nf6 5. O-O a6 6. Bxd7 Nxd7 7. Nc3 e6 8. Bg5 Qc7 9. Re1 cd 10. Nxd4 Ne5 11. f4 h6 12. Bh4 g5 13. fe gh 14. ed Bxd6 15. Nd5 (a Typical Tal move! Houdini says the position now goes to -2.0 for Tal) ed 16. ed+ Kf8 17. Qf3 and Black forfeited on time.

The computer says Tal is losing, but it is not so easy to meet the threats on the board. And so Tal leaves the game as he found it, playing aggressively, speculatively, for the fun and joy of the game.

No column for the summer

I have been writing this column for more than four years, and am going to take a break for the summer, until late August.

In the last year, I have put a lot of energy into chess — playing, studying, writing about it — and I want to take some time to do some self-evaluation, decide whether I want to keep doing as many chess things as I have been doing.

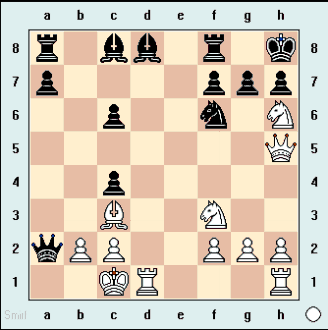

This week’s problem

Here Tal finds a neat mating attack against former world champion Vasily Smyslov, who had also defeated Botvinnik for the world championship (in 1957) only to lose a rematch the following year.

After the crucial first move, White mates in no more than four moves.

Location:

As those of us who are Red Sox fans know all too well, sometimes the favored competitor that has a history of winning somehow finds a way of winning, even when it appears that he or she does not deserve it.

Defending Champion Gata Kamsky and four-time, and twice defending Women’s Champion Irina Krush both came from behind to become part of three-way ties for first place in the 2014 United States Open and Women’s Championships, and then went on to win their playoffs.

Although Kamsky was undefeated after 10 rounds, he had only won twice, and never been leading the tournament, and had a score of 6-4. Earlier in the tournament, he had predicted there would be a new champion this year.

However, the two leaders, Alexsandr Lenderman and Varuzhan Akobian, had scores of 6½ - 3½, and were scheduled to play each other. Both played hard, continuing to play for a win even as the game simplified into a drawn rook and pawn ending.

Lenderman, the early leader of the tournament, playing White, said he had no idea how the playoff worked because he wasn’t planning on drawing the game. Meanwhile, Kamsky managed to win a difficult game against Josh Friedel to force a three-way tie at 7-4.

Kamsky had the best tie breaks, and was therefore designated to play the winner of an Armageddon playoff game between Akobian and Lenderman. Akobian, playing Black, needed only a draw to advance to the final game against Kamsky.

He found a pretty Bishop sacrifice, which led to a forced win. The finals consisted of two games played at a time control of 25 minutes for game with a five second for move increment. After drawing the first game with the black pieces, Kamsky won the second with White, to claim the championship.

Krush, like Kamsky, went undefeated in the tournament. However, she complained of a mild fever during the tournament, and had given up three straight draws going into the penultimate eighth round, where she defeated her main rival, four-time champion Anna Zatonskih.

In the last round, Tatev Abrahamyan, with 5½ - 2½, won her game early; if either Krush or Zatonskih, both with 6-2, won, she would have been eliminated. However, both drew, setting up a three-way tie at 6½, 2½ .

In the Armageddon playoff, Abrahamyan, playing Black, forced a draw by perpetual check against Zatonskih, to set up the final against Krush. Krush won the first game with White, then held on for a draw in the second game with Black to win the title.

Ashritha Eswaran

After achieving an even score after five games, Ashritha Eswaran faded to finish with 3½ - 6½.

It is still unprecedented for a 13-year-old girl to play in a U.S. championship, and she certainly demonstrated that she can compete with the best women in the country.

Sam Shankland

Although a poor start disqualified Sam Shankland from a chance of winning, he had the distinction of defeating the tournament leaders on two occasions: Lenderman in the sixth round and Akobian in the ninth round, to ultimately finish with a score of 6-5.

Lenderman – Shankland

U.S. Championships

St. Louis 20141. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 Nf6 4. Nc3 Be7 5. Bf4 O-O! 6. e3 Nbd7 7. Qc2 Shankland usually plays 2…c6, and Lenderman seemed a little surprised by the opening 7. c5 is more common.

7... c5 8. Rd1 cxd4 9. Rxd4 Qa5 10. Rd1? Lenderman thought a long time before this move, which leaves him with an inferior position. GM Finegold commented that 10 Bg3 is the only move played in top-level play. 10..Nb6 11. Nd2 Bb4 12. a3 Bxc3 13. Qxc3 Qxc3 14. bxc3 Bd7. Black has a slight edge due to White’s weak c pawns.

15. Be5 Ba4 16. Rb1 Nfd7. Black’s Bishop is strong, his Knight threatens e5 and he is about to seize the c file and win a pawn. 17. Bd6 Rfc8 18. cxd5 exd5 19. Nf3 The pawn on c3 will fall anyway, so White decides to develop his Knight.

19... Rc6 20. Be7 Rxc3 21. Bb4 Rc7 22. Be2 Nc4 23. Nd4 Nf6 24. Rc1 Rac8 25. Nf5 Nd6 Black has a clear advantage: in addition to the pawn, his rooks are doubled, his Knight is well posted, and his Bishop is annoying, Here, Shankland accurately calculates how to simplify the game to an easier win. 26. Rxc7 Rxc7 27. Ne7+ (27. Nxd6 Rc1+) Kf8! (better than Rxe7 28. Bxd6) 28. Ng6+ Ke8 (28... hxg6?? 29. Bxd6+ )29. O-O. Excellent play by both sides! But Black is still a clear pawn up.

29... Nde4 30. Ne5 b6 31. Ra1 a5 32. Be1 Nc3 33. Bd3 Nfe4 34. Nf3 Bb5 35. Bxb5+ Nxb5 Forcing the trade of White’s most active piece. 36. a4 Nbc3 37. Nd4 Rc4 38. f3 Nc5 39. Bxc3 Rxc3 40. Nb5 Rxe3 41. Nc7+ Kd7 42. Nxd5 Rb3. Although Black has not increased the material advantage, he has used his better piece position to reach a 2 versus 1 on the Queen side and the Black’s a pawn is very weak. Houdini says Black is up 2.1 and White is lost.

43. Rd1 Kc6 44. Ne7+ Kc7 45. Rd4 Ra3 46. Nd5+ Kc6 47. Ne7+ Kb7 48. Rd8 Rxa4 49. Rf8 Rd4 White resigns (Black will easily Queen his a pawn).

New York State Open

The Tiki in Lake George is the kind of motel that gives tourism a bad name. It features fake Polynesian décor, mediocre food, and has seen better days. Still, it is an excellent venue for a chess tournament the week before the main tourism season starts on Memorial Day weekend, and the Continental Chess Association, the largest sponsor of tournaments in the United States, does well by chess players to negotiate a discounted rate for chess players.

The New York State Open is an excellent opportunity for Capital District chess players to play against players from outside the region.

The Open section was won by Boston GM Alexander Ivanov with a 5-0 score; two local players, Albany club champion Jeremy Berman and Mike Mockler, had the opportunity to play him.

Twelve of the 32 players in the Open section were from the Capital District, including Martha Samadashvili, who drew a master and an expert on the way to a score of 2½ - 2½.

For the second year in a row, the Senior section (limited to players over 50 with a rating under 1910) was won by a local player: Alan LeCours, who tied for first with 4 ½ - ½, ahead of 20 other players, including five locals.

Thirty-four players, including five locals, competed in the under-1610 section; Albany player Thomas Clark tied for second with 4-1, raising his rating over 1600.

This week’s problem:

Cherchez la femme

In the problem below, White has doubled rooks on the e file threatening Rxe8, which would lead to mate except for the fact that the Black rook on e8 is defended by both a rook and a queen. How does White win?

Readers may reach chess columnist Peter Henner by e-mail at

Location:

On April 1, Chessvibes.com reported that United States President Barack Obama and Russian President Vladimir Putin issued a joint statement announcing that they would meet later this month to play a game of chess.

Although President Obama stated last month that the United States does not see the current situation “as some Cold War chessboard,” he now acknowledges that “the game of chess goes beyond any possible conflict… between the United States and Russia. This is an expression of hopes and aspirations of people in every country to solve all conflicts between us between the boundaries of the 64 squares.”

President Putin added, “The stakes are very high. The game will be of utmost importance for the new world order.”

Although both Obama and Putin have some experience with chess, they both will be assisted by famous grandmasters. Obama is expected to be assisted by three-time U.S. Champion Hikaru Nakamura, and former world Champion Garry Kasparov, a Russian opponent of Putin who characterized Putin as “a decent calculator [who] likes to attack, but… lacks… positional judgment.”

Another former world Champion, Anatoly Karpov, currently a member of the Russian Parliament, is expected to assist Putin.

(Editor’s note: Yes, this is an April Fool’s Day joke.)

Anand wins Candidates Tournament,

earns rematch against Carlsen

Many people believed that Vishy Anand would withdraw from high-level chess competition after losing the world championship last year. However, Anand, at 44, the oldest competitor, won the eight-man double round-robin Candidates tournament in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia, and will play Magnus Carlsen for the championship in November.

Anand was undefeated, scoring 8 ½ - 5 ½, to place first by a full point over Sergey Karjakin who was second with 7 ½ - 6 ½. Anand won his first-round game against Levon Aronian, ranked number two in the world. Aronian recovered to tie Anand after 7 rounds, but lost his last two games to finish in a tie for 6th-7th, with 6 ½ - 7 ½.

Chess has come a long way in the last hundred years: The prize fund for the tournament was €420,000, with Anand, as the winner, receiving €95,000, and even Veselin Topalov, who finished eighth with 6-8, receiving €17,000.

Deepak Aaron scores big

at Eastern Class Championship

Deepak Aaron, the strongest player to grow up in the Capital District, came home on spring break from Georgia Tech, where he is studying chemical engineering, to play in the Eastern Class Championships in Sturbridge, Mass.

He defeated Grandmaster Alexander Fishbein and drew GMs Alexander Ivanov and world champion contender Gata Kamsky, and raised his rating 35 points, to 2465.

Kamsky placed first with 4 ½ - ½, ahead of GMs Sam Shankland and Aleksander Lenderman, who tied with Deepak and Victor Shen for 2nd – 5th, with 4-1 and Ivanov and Fishbein with 3 ½ - 1 ½.

Other Capital District players: in the Expert section: Dean Howard 1 ½- 1 ½, Peter Henner 1 ½ - 2 ½. Class A: Dilip Aaron 2 ½ - 2 ½, Martha Samadashvili 2 ½ - 2 ½, Scott Boyce 1 ½ - 2 ½. Class B: Zaza Samadashvili 3 ½ - 1 ½, Jonathan D’Alonzo 3-2, Sandeep Alampalli 2 ½ - 2 ½. Class D: Joseph D’Alonzo 3-2.

Sam Shankland is a senior at nearby Brandeis University, and is establishing himself as one of the strongest players in the U.S. His uncle, my endodontist, is happy that his nephew may have found a career doing something where he may be one of the best in the world.

Shankland was undefeated when he met Kamsky in the fourth round. Kamsky sacrificed a piece for an attack in a game that drew a crowd of spectators, including me.

Kamsky-Shankland,

Sturbridge, Ma. 3-16-14

1. d4 Nf6 2. Bf4 d5 3. e3 e6 4. Nd2 c5 5. c3 Nc6 6. Ngf3 Bd6 7. Bg3 O-O 8. Bd3 Qe7 9. Ne5 Nd7 10. Nxd7 (f4 is more common) Bxd7 11. Bxd6 Qxd6 12. dxc5 Qxc5 13. Bxh7+!? Kxh7.

14. Qh5+ Kg8 15. Ne4 Qc4 16. Ng5 Rfd8 17. Qxf7+ Kh8 18. Qh5+ Kg8. The crowd of spectators was at its thickest at this point, at least 10 of us. Kamsky thought for a long time, at least 10 minutes here, obviously looking for a win rather than a draw by perpetual check. Looking at the position, I saw that Kamsky had an attack, but I didn’t see how he could win, and thought he might have to settle for a draw since he was behind in material.

19. Rd1! e5? After this move, Houdini downgrades Black’s position from - 2.4 to -3.3 20.Qf7+ Kh8 21. e4 Ne7 (Black must give the piece back to prevent Rxe5) 22. Qxe7 Bb5 23. Rd2 Qxa2? (desperation, but Black is lost anyway). 24. Qf7 Qa1+

25. Rd1 Qxb2 26. Qh5+ Kg8 27. Qh7+ Kf8 28. Qh8+ Ke7 29. Qxg7+ Kd6 30. Rxd5+ Kc6 31. Qf6+ Black resigns.

This week’s problem

As a young man, future world champion Wilhelm Steinitz was known as the “Austrian Morphy.”

The American Paul Morphy was perhaps the most brilliant chess player of the 19th Century — he traveled to Europe in 1857, defeated all the best European players, and then retired from chess, reputedly because there was no one strong enough to compete with him.

Here Steinitz finds a neat mate in 3.

There is an old story about a lively debate that supposedly took place at the Marshall Chess Club in New York City in the early 1960s. One of the debaters vociferously argued that chess players were obviously smarter than the general population.

However, the discussion ended suddenly when his adversary simply responded, “Then how do you explain Bobby Fischer?”

I am not aware of any studies showing any correlation between chess strength and I.Q. I don’t know anyone who admits to being a member of Mensa, but I suspect that very few of them are actually strong chess players.

Conversely, I know of many chess players rated over 2000 who have never distinguished themselves in any other intellectual activity.

Still, chess players, especially strong chess players, tend to be capable of mental feats that appear miraculous to the general public. For example, most chess players rated over 1800 can play “blindfold” chess, where the player is told the moves, and plays without actually having a board and pieces in front of him.

My wife is amazed that I do not write down possible entries in Sudokos; I keep the possibilities in my head until I am sure of the number to enter in a particular square.

The newest world Champion, 23-year-old Magnus Carlsen, solved complex jigsaw puzzles before he was 2, built advanced Lego models at the age of 4, and knew the area and population of all of Norway’s 430 municipalities at the age of 5. Although he worked very hard to become a Grandmaster by the age of 13, and ultimately to become world champion, Carlsen clearly had tremendous talent, both for chess, and for other intellectual activities.

Training, a supportive family, and hard work alone could not have produced a champion; consider the talented Polgar sisters whose father set out to train them to be chess wizards. Although Sofia became an International Master, and Zsuzsa a Grandmaster, only Judit had the talent to reach the highest levels of international competition.

Gates – Carlsen

Recently, Carlsen played an exhibition match against Bill Gates on Norwegian television. Gates is obviously a very successful businessman, and, while the extent to which intelligence is necessary for such success is another question, he is obviously not stupid.

Carlsen needed all of 12 seconds and nine moves to checkmate Gates (who played White) (a video of the game is on Youtube). 1. e4 Nc6 2. Nf3 d5 3. Bd3? (this move shows that Gates knows nothing about chess openings) Nf6 4. ed Q:d5 5. Nc3 Qh5 6. 0-0 Bg4 7. h3 Ne5 (Carlsen would normally not play a move like this — he described it after the game as “a cheap trick,” but he correctly believes that Gates will fall for the trap by taking the Bishop) 8. hg Nf:g4 9. N:e5?? Qh2 mate.

Chess strength

If native intelligence is not the sole, or even the main, determinant of chess strength, what is? There are many players who study very hard and very long and whose ratings never change.

In the Capital District, there are about 20 players, including myself, rated over 1800, who have been playing a long time, who were or are experts at one point, but who have not made it to master. Why not?

The current issue of Chess Life has an article by a man in his early 40s, describing his efforts to become a master over the next few years (he has also established a blog, ontheroadtochessmaster.blogspot.com.) In 2011, when he was rated in the 1500s, he established a goal of a rating of 1800, by the end of 2012, an expert rating of 2000 by 2015, and to become a master by 2020 (a rating of 2200).

He achieved a rating of 1721 in 2011, but, in three years, he has yet to break 1800. I would not be optimistic for him.

When I closed my law office last year, I decided to seriously attempt to become a master.

First, I spend about an hour a day solving tactical and endgame problems on a website, chesstempo.com, that I would highly recommend.

Second, I carefully analyze all of my games, with the aid of a computer, to see what I did right and what I did wrong.

Third, I do “solitaire chess” or “guess the best move” exercises, where I play over a Grandmaster game trying to guess the moves made.

Fourth, I try to review three to five high-level chess games a day.

Fifth, I try to do some formal study, some of openings, some of endgame theory, and some through books of general instruction. If I had more time, I might review some theoretical texts that have been written by great players over the years.

I would like to study 20 to 30 hours a week, but rarely do that much. Certainly, there is enough material to study 50 to 60 hours a week for the next few years. But, even if I do spend this time and effort, it is by no means clear that my rating will improve. Although I still believe that I have the ability to improve, it is possible that I have reached my maximum strength.

Tata Steel (Wijk aan Zee)

The 76th Wijk aan Zee (Netherlands) tournament (now known by its current sponsor as the Tata Steel Chess Tournament), one of the strongest annual chess events, was won by Levon Aronian, who is the only player in the world to be rated over 2800 besides Carlsen. Aronian clinched first place before the last round by scoring eight points in the first 10 rounds.

The American Hikaru Nakamura, ranked third in the world behind Aronian and Carlsen, tied for 8th-9th place with a score of 5-6.

This week’s problem

In the 11th and last round of the Tata Steel Chess Tournament, Aronian played the strong Dutch player and hometown favorite, Loek Van Wely. Aronian described the game as his most interesting game in the tournament.

Although he had clinched first place, he was playing hard for a win, had broken through Van Wely’s Dutch Defense, and had missed forced wins on moves 35 and 37, before making a time pressure mistake on move 38, which permitted Van Wely to force mate.