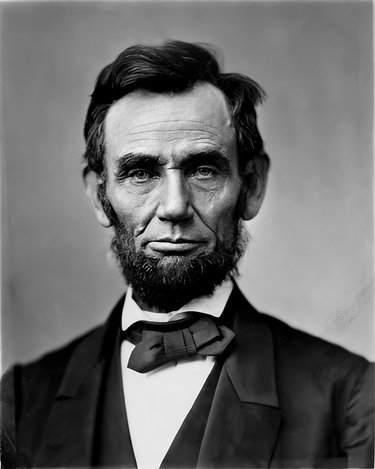

In an Aug. 7, 1863 letter to Horatio Seymour — the fractious governor of New York who opposed the Emancipation Proclamation — Abraham Lincoln stated with resolve, “My purpose is to be, in my action, just and constitutional; and yet practical, in performing the important duty, with which I am charged, of maintaining the unity, and the free principles of our common country.”

I wish Lincoln were alive today so I could ask him whether his definition of common country included meeting the needs of all, the enduring question of political economy.

“Common country” had been on his mind from the beginning of his presidency. On Nov. 20, 1860, two weeks after winning an election with less than 40 percent of the vote — a civil war waiting in the wings — he addressed a group of “Friends and Fellow Citizens” in Springfield, “Yet in all our rejoicing let us neither express, nor cherish, any harsh feeling towards any citizen who, by his vote, has differed with us. Let us at all times remember that all American citizens are brothers of a common country, and should dwell together in the bonds of fraternal feeling.”

Unity. Common country. Dwell together. Fraternal feeling. Treating others with “patient tenderness and charity,” a trait one biographer linked to Lincoln.

Any soul who’s been to therapy and cleansed his mind of the ideological constructs that sabotage happiness and drive wedges into relationships, tends to treat others with patient tenderness and charity taking their needs into account.

As a patient — coming from the Latin patior, to suffer — the “cured” soul had his story listened to with an open heart, his needs had been recognized as worthy of attention so, when he meets travelers of divergent points of view, he is able to open his heart and see their stories as valuable as his own, their needs as important as his.

When a person’s story is not heard, when his needs are denied or minimized — certainly not met — an enduring wound is inflicted on the psyche. Oftentimes the wounded soul angrily deflects the pain by projecting the hurt onto others, making them pay for the loss.

Vindictively, he speaks in ways that are divisive and argumentative, adopting what the late clinical psychologist Marshall Rosenberg called, “jackal language.” Justice for him is not meeting the needs of all equally but getting even, often in oblique ways. For decades the esteemed Brandeis sociologist David Gil pointed out how this kind of invective incites retributive counter-violence.

Carl Rogers, one of the pioneering psychotherapists of the 20th Century said on many occasions that, when people come to therapy seeking help, they arrive emboldened by a façade.

The façade was a tool, a strategy, they adopted to insure that their needs were met but they had reached a point where such walled-in existence and its accompanying jackal language were debilitating. Disunity and division were killing them.

They did not know, when they first entered the therapist’s office, that they were searching for a new identity that required digging deeper into the self. Freud described the procedure as, “one of clearing away the pathogenic psychical material layer by layer”; it was like “excavating a buried city.”

The excavation allows a patient to let go of the ideas, acts, ideologies, and all the tools that support façade-based living. All he wants is to stop the mind from warring with the heart.

The great 20th Century thinker, Norman O. Brown, was possessed with understanding what caused people to adopt divisiveness and rage as a way of life and whether such sufferers might find release through renewed consciousness.

In his 1966 classic, “Love’s Body,” Brown titled the fourth chapter “Unity.” The first sentence begins, “Is there a way out; an end to analysis; a cure; is there such a thing as health?”

That is, can a person, a society, ever heal from the wounds it has inflicted upon itself by disregarding the stories of some, by denying that their needs have validity?

Brown asks that question on page 80 and by the final page of text we see (1) there is a way out of disunity, out of psychological and societal suicide; and (2) there is such a thing as health and it can be practiced and achieved.

Brown also concludes that there is no end to self-reflective analysis and, as far as a “cure” goes, the wound never fully heals. But the struggling soul realizes, like Lincoln, that, when he recognizes the needs, stories, and history of others as equal to his own, he welcomes even those outfitted in rage into the common country. Personal value is based not on what one deserves but on what one needs.

But such an ideal is achieved only when we forego jackal language and begin to speak to each other nonviolently. The Center for Nonviolent Communication, which Marshall Rosenberg founded decades ago, offers four strategies to help a society move in that direction.

The first is to speak to each other about what we are seeing, hearing, and touching without making a judgment or evaluation. Rosenberg says, “When we combine observation with evaluation others are apt to hear criticism and resist what we are saying.” Generalizations like “You, right-wingers ...” only add to division.

The second practice is to develop a vocabulary of feelings where we point out where our needs are being met or not met. If we “clearly and specifically name or identify our emotions,” Rosenberg says, “we can connect more easily with one another.” Abstractions like “I feel I never got a fair deal” intensify anger.

Third, everything we do must be in the service of needs. Rosenberg says at the level of needs, “we have no real enemies, that what others do to us is the best possible thing they know to do to get their needs met.”

Miscommuniqués, therefore, do not call for blame or shame or hate but for reclarification. The focus should remain on the source of the hurt and the wish to be treated more fairly. Within such a framework we are all likely to express feelings and needs and forego recounting tales of past injustices and hardship.

The final prerequisite for nonviolent communication is that, when speaking to others, we make requests as opposed to demands. When a person hears a demand, he sees submission and rebellion as his options. Rosenberg says, “Either way, the person requesting is perceived as coercive, and the listener’s capacity to respond compassionately to the request is diminished.”

How well the members of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa knew that, if a common country is a goal, the stories of all must come out.

President George H. W. Bush understood this even in the face of defeat. On White House stationery, in pen and ink, he wrote to his successor on Jan. 20, 1993:

Dear Bill,

When I walked into this office just now I felt the same sense of wonder and respect that I felt four years ago. I know you will feel that, too.

I wish you great happiness here. I never felt the loneliness some Presidents have described.

There will be very tough times, made even more difficult by criticism you may not think is fair. I'm not a very good one to give advice; but just don’t let the critics discourage you or push you off course.

You will be our President when you read this note. I wish you well. I wish your family well.

Your success now is our country's success. I am rooting hard for you.

Good luck — George

Forty-One like Sixteen knew all about common country.

A few minutes into Federico Fellini’s “Amarcord,” even the casual viewer comes to see that the kids the director portrays — in his hometown of Rimini, Italy in the 1930s when he was a teen — were smart-ass airheads, without vision or purpose, unable, or unwilling, to transcend the roles history assigned them — as was the case with their mothers and fathers, and their parents before them.

You’d think Fellini had read Paul Goodman’s “Growing up Absurd” or Émile Durkheim on anomie.

But “Amarcord” is not a small-town biopic; it’s an artistic projection of Fellini’s heart as a kid, a feeling-memory projected onto the screen when Fascism had control of Italy’s mind. Compelled to escape the roles society allowed, Fellini left for Florence in 1937 at 17.

And though the movie is the work of an exile, it is an homage of deep feeling to the life he once lived. He treats each “character” of his youth with the vivid imagination of a poet-philosopher; he wanted them all to live forever — even the prurient parish priest and his teach-by-the-book teachers who took up the garb, and saluted with the vigor, of Fascists. (No resister is portrayed.)

And because Fellini allows each character — high and low — to have a say, “Amarcord” is an expression of dignitas. Each person comes on screen, tells his story, and waits in the wings until called again. And, after you’ve seen the movie a few times, you realize the town is a character as well. She draws you in.

“Amarcord” is more than a memoirist’s dream then, it’s ethnography; Fellini catches each person in his living-day-to-day, speaking-unselfconsciously self — alone or with the family, or maybe with a smart-ass peer group who embrace the Nazis in their Fascist youth uniforms.

“Amarcord” fits into the category of movie-making I call autobiographical comedy. Woody Allen’s “Radio Days” fits as well. Both films create a vision of a past when a person’s moral consciousness is born.

I love “Radio Days” and I love “Amarcord” but, in the personal memoir category, I vote for Fellini; Woody’s lingua franca has an edge, Fellini speaks in softer tones and treats his peeps with compassion. The viewer wants to visit Rimini but not the Rockaway Beach of Woody Allen.

Every time I see “Amarcord” I’m drawn to those subculturally-predelinquent, smart-ass teens who find fun in sadistically teasing the vulnerable — and they’re always fired up with sex.

“The Maestro” says in his memoir “I, Fellini” that, “I would stand with my young friends and we would study the women and speculate on who wore a brassiere and who didn’t. We would position ourselves at the bicycle stand in the late afternoon, when the women came for their bicycles, so we could watch from behind with the best view as they sat down on their bicycles.”

At some point in “Amarcord,” we’re introduced to those rears as they squat down upon the seats and morphously slide down their sides. Fellini says, “The sharp saddles slipped rapidly under the shiny black satin skirts, outlining, swelling, expanding, with dazzling gleams and sparkles, the biggest and finest bums in the whole of Romagna.” All fodder for future sexual fantasies.

Fellini thought the paths society offered did not extend beyond the ordinary. He says when he was leaving town he thought his “friends would be envious because I was leaving, but far from it. They were perplexed. They didn’t feel the drive to leave that I did. They were content to live in Rimini and were surprised I didn’t feel as they did.”

The word “Amarcord” comes from the dialect-Italian m’arcôrd which means “I remember” so we tend to think the movie is about memory.

But, in a 1980 interview with “Panorama” magazine, Fellini said no, “It is not memory that dominates my films. To say that my films are autobiographical is an overly facile liquidation, a hasty classification. It seems to me that I have invented almost everything: childhood, character, nostalgias, dreams, memories, for the pleasure of being able to recount them.”

But that’s not exactly true, and why the Canadian-born filmmaker Damian Pettigrew called his feature documentary: “Fellini: I’m a Born Liar.”

The undying adolescence of Fellini’s smart-alecky posse bored into his consciousness as well.

Twenty years earlier, he lit up the screen with a vision of what those guys looked like in their late-twenties in “I Vitelloni.”

“Vitelloni” in Italian means little bullocks, overgrown calves, little-boy-bulls — that sort of thing — and metaphorically means layabouts, lazy loafers, do-nothings. Italians have a name for that type today, “Mammoni.” Mommy’s pets.

Fellini’s “Amarcord” co-screenwriter Ennio Flaiano (the third was Tullio Pinelli) said that he thought “vitelloni” came from “vudellone, the large intestine, or a person who eats a lot. It was a way of describing the family son who only ate but never ‘produced’ — like an intestine, waiting to be filled.”

Fellini said the title came from what an old lady called him when he got caught pranking as a kid: vitelline! He said the vitelloni in Rimini shined “during the holiday season, and waiting for it takes up the rest of the year.”

He returned to Rimini in 1945 only to see a town torn to pieces. He said it “looked like a sea of rubble. There was nothing left. All that came out of the ruins was the dialect, the familiar cadences, a call of ‘Duilio! Severino!’, those strange names.”

And those who have such names in “Amarcord” did live in Rimini.

One was the beautiful, “sexy” hairdresser, Gradisca, who, when she walked down the street, the teen bullocks get “hot and bothered” and started making sexual gestures with arms and hands.

Titta, the boy who plays Fellini in the movie, puts the moves on Gradisca one day when he finds himself alone with her in a movie theater; she looks down at his hand in condescension.

The historical Fellini could not escape her scent; he says, I “went looking for Gradisca many years later in the country near Comasco.”

He was told she got married to a sailor (a cousin) and moved to “a wretched little village, then a muddy part of the river.”

When he drove there (in a Porsche), he came upon a little old lady hanging out wash in her garden. He got out and said, “Excuse me ... Where does Gradisca live?”

The old woman said, “Who’s looking for her?”

Fellini said he was, that he was an “old acquaintance: ‘Can you tell me where she is?’ ‘I am Gradisca,’ said the old woman.”

There before him stood the burning sexual flame of his youth but she “had lost every single trace of that triumphant, carnival glitter of hers. When I came to work it out, in fact, she must have been sixty years old.”

The Gradisca of “Amarcord” is beautiful, vivacious, and a “teaser” robed in red, whom every man in Rimini wants to “have a chat with.”

In real life, “Dressed in black satin that flashed in a steely, glittery way,” Fellini says, “she was one of the first to wear false eyelashes. Inside the café [Commercio] everyone has his nose to the glass. Even in winter Gradisca looked as if she has just stepped out of a band-box, with curls, the first permanent wave.”

In “Amarcord,” Gradisca and all the townspeople she lives among, live without wrinkle or care. In “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” John Keats says that’s one of the benefits of art:

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

With such thinking, no one loses.

But one wonders — with the coronavirus running rampant — to what extent Keats and Fellini, and all their talk of art, can help assuage the sorrow weighing on the American soul.

People of a certain age will recall with fondness that, when the extended family gathered on Halloween night for food, conversation, and games, some of the kids got carried away with laughter. You could hear them across the room.

One of the games our family played on the hallowed eve — of el Día de los Muertos — was ducking or bobbing for apples. When I tell older folks about it, they say their family played it too.

Several dozen apples were set afloat in a large metal wash tub filled with maybe a foot of water; one of the adults overseeing the project — while the kids turned their backs so as not to cheat — pressed a coin into the flesh of one of the apples, covered the scar and set it afloat with the rest; you couldn’t tell which one it was. Back then, the prize was a dime or a quarter, which everyone liked.

One by one — I think by age — we kids knelt beside the tub and plunged our head deep down under to pin the winner against the side or bottom of the tub with grinned teeth.

It wasn’t easy; there was a time-limit; some of the kids couldn’t hold their breath and quickly shot back up gasping for air. The sorry soul took two or three deep breaths and was back under.

Part of the giddiness came from how crazy a person got, getting wet — hair, shirt, the floor — some panicked when they hit the water but it never stopped them. An aunt or an uncle stood by with a towel to help mop the sops off.

And someone always got the coin. Everybody was happy, not just the person who “won” but everybody because it was such good fun. I know it had to do with — at a subconscious level — reaffirming family. Plunging into a tub of water was a small price to pay.

No one in the family’s collected data on the event and I don’t recall anyone who won, or even if I did, but there was no envy; winning was luck.

And at no time were we told that a win signified something more than the coin, for example that the game foretold something about the future.

But for centuries in Europe, communities believed that that game, and divination games like it, foretold what was in store for the winner — he would be first to get married or the first to have a child. At some weddings now, the bride throws her bouquet into a group of “eligible” women and the person who catches it will be the first married.

Games of future-telling on Halloween are remnants of the life of herd-tending communities who considered it the eve of a new year — on November First, a new life-cycle began.

The famed Irish writer, Patrick Joyce, says in his beautiful two-volume classic “The Social History of Ancient Ireland,” that the herd-tending communities divided “The whole year .... into two parts — Summer from 1st May to 1st November, and winter from 1st November to 1st May.”

On the eve of the new year, when the light of day had already shifted, the pensive mind attended to the other world and the soul grew open to the future.

Even kings wanted to know. Ireland’s fifth-century Dathi, when visiting Sligo one Halloween, told the local druid to find out his future.

The story says the priest went up a hill and spent the night thinking; when he came down, he told Dathi what he saw — ancient sources say it all came true.

For those of lesser means, and without a druid to call upon, bobbing for apples and the “nut game” were their Halloween seers.

In the nut game, a young couple wanting to know what was in store for them, placed two nuts by the fireplace; the woman was one, the man, the other. How the nuts behaved in the heat foretold things to come. Friends and family looked on with delight.

If the nuts burned together, the couple would be married; if it took a long time, their marriage would last; and if the fire burned bright, happiness would be theirs.

But if one of the nuts got too hot and jumped away from the other, the pair would go their separate ways — there’d be no wedding — and the nut who jumped away was responsible!

One of the paradoxes of Halloween is that its “ceremonies” have long dealt with not only the future but the past as well. The hallowed eve was a time when the community thought about the dead: friends, relatives, and saints who helped along the way.

Ethnologists say on Halloween the spirits of the dead came around the house looking for warmth, a cup of tea, and conversation, and then they’d be gone — the extended family in attendance.

Nobody ducks for apples any more. At some point, parents didn’t want their kids sticking their salivary mouths into a pool of water where other salivary mouths had been, even those of kin.

The game changed to chasing an apple on a string but the giddy laughter of diving into a tub of splashing water was gone — plus (sociologically) the family had radically changed.

Now, with the coronavirus upon us, bobbing for apples will never be played again, and disappear from cultural consciousness, except for the ethnologists. The human family has one less tool to consider its future.

In the old days, the ghosts wanted to come inside for warmth but now, with the virus, “inside” is a place of danger, an enemy, and, with winter coming (we’re told) it will worsen. Where will the dead go?

And what other means do we have to consider our future: as a family, a state, a nation, a species? We’re still struggling to talk to each other without ill-will and rancor — wasting precious psychological energy.

Halloween? Every day is Halloween now. Every day is the eve of a new dawn. Some of us have learned the benefit of wearing a mask but a lot are still having a hard time speaking with an open heart.

Boo!

Let’s start with a short culture quiz.

The first question is: Which is the greater work of art: Andy Warhol’s “Brillo Box” (1964) or Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937)?

You have until the Final Jeopardy! song ends to give your answer.

And the second question is: Which is a greater song? Franz Schubert’s “Ave Maria” (written in 1825), or Willie Dixon’s “Back Door Man,” which Howlin’ Wolf premiered in 1961?

With respect to the first question everybody of a certain age knows who Warhol and Picasso are, so their choice of painting might be more or less à chacun son gout.

In terms of the two composers, Schubert is 99 times better known than Dixon and his song has been played in practically every church on Earth. With Willie Dixon people ask: You sure you don’t mean Willie Mays?

How a person responds to both questions is a measure of that person’s view of “the sacred” and “the profane,” a division that derives from the value a person puts on people and things when constructing a vision of the world. Despite the denial of many, it’s a primary category of thinking.

When those in the “sacred” camp hierarchize, they use metaphors like holy, God, divine grace, and virgin birth. The images are so powerful that sometimes people forget they’re economic variables reflecting the price put on something. Concepts like value, worth, compensation, payoff, and “equity” are part of it.

Incidentally, when ordering their world, some people decide to reject hierarchy altogether — the basis of anarchist thinking — which means a person is equal to God. Holy God is holy Me and holy Me is holy All — what Allen Ginsberg announced in his footnote to “Howl.”

The major problem with Schubert’s “Ave Maria” is not that it’s soppy with emotion but that, exegetically speaking, it does not reflect the story that happened: the story of an angel appearing to a young woman telling her she will have a child, not only that but the child will be a god, and not just any god but the savior the prophets of the Hebrew Scriptures longed for for centuries.

Even taking into account à chacun son gout — how many people can say that “Ave Maria” changed their lives or shook up the way they think?

On the other hand, Willie Dixon is not just one of the great songwriters of all time but a man who penned words that allowed Black men to speak about their identity in direct and truthful ways. He said, men, we have a need to express our love just like white men.

Rolling Stone magazine ranked Willie 51st on its best-ever-songwriter list — Dylan is 1, McCartney 2, Lennon 3, and Chuck Berry 4 — but Willie deserves to be right there with them because he helped restructure identity.

As a performer, Willie — all six foot, six of him — could put a song across, but the singing of his songs is most associated with Muddy Waters, the greatest blues artist of all time. He’s as good as Sinatra.

In January 1954, Chess Records came out with a forty-five with “Hoochie Coochie Man” on Side A — Muddy singing and on guitar; Willie is billed as Songwriter/Composer.

The song starts with a stop-and-go bump-and-grind heavy bass rhythm and then words flow, telling Black men they no longer have to hide their manhood. It’s an anthem of liberation.

On YouTube, you will see Muddy proclaiming the message, not strutting up and down the walk like a banty rooster but laying out the facts of Black identity as if making a presentation before a Fortune 500 company — but is in no way matter of fact.

Muddy begins:

The gypsy woman told my mother

Before I was born

I got a boy child’s coming

He’s gonna be a son of a gun

He gonna make pretty womens

Jump and shout

Then the world wanna know

What this all about

And who’s that son of a gun?

Muddy says:

But you know I’m him

Everybody knows I’m him

Well, you know I’m a Man

Yeah, everybody knows I’m him

And when you hear his emphasis on eev-ree-body, you realize Mr. McKinley Morganfield — Muddy’s birth name — is not singing “Hoochie Coochie Man” he is Hoochie Coochie Man.

Dixon wrote more than 500 songs. Two others he gave to Waters are “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” and “I’m a Natural Born Lover,” and to Wolf he gave “Little Red Rooster,” which the Stones shared with the white world in November 1964 — introducing that world to Willie Dixon and the electric blues of Chicago.

By saying how a little red rooster handles the barnyard Willie was giving all men a context to explore their sexuality.

The world is a strange place though for, as “Hoochie Coochie Man” was making the rounds at Chicago’s radio stations, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from that city was visiting his relatives in Money, Mississippi — 100 miles north of Lynchburg where Dixon was born — and, while there, was beaten, shot, and submerged in a river tied to the fan of a cotton gin to keep him down.

The facts reveal that, when Emmett went into town to buy a pack of gum one day, the 21-year old owner of the store, Carolyn Bryant, said the boy got sassy, he whistled, and on the way out shot back, “Bye baby!” Carolyn’s husband, Roy, and his half-brother, J. W. Milam, showed up and took the story from there.

Sixty-two years later, the lady-judge storekeeper whose words sentenced Emmett to death, said she made it up; there was no sex-stuff. It was her white supremacy speaking, her repressed-sexual libido was pining for a Hoochie Coochie Man.

When the United States established a draft in World War II, Willie got messages to come get fitted for an army hat but he threw them in the trash, forcing officials to come to one of his gigs and arrest him.

Willie told the draft board it was nothing personal; he couldn’t serve because he was a conscientious objector — 30 years before Muhammad Ali!

Willie said that American society said he was a non-person and a non-person can’t fight in war because there ain’t no one there!

He was put in jail but raised such a ruckus that the draft board classified him 5-F and set him free; the whole story is in Willie’s riveting, and disarming, autobiography (with Don Snowden), “I Am the Blues.”

How can a person, Willie kept saying, help a system stay afloat while it’s dragging him down tied to a piece of a cotton gin?

Toward the end of August Wilson’s “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” Ma Rainey declares, “White folks don’t understand about the blues. They hear it come out, but they don’t know how it got there. They don’t understand that’s life’s way of talking. You don’t sing to feel better. You sing ’cause that’s a way of understanding life.”

And that’s what Los Angeles Clippers Coach Doc Rivers was trying to figure out last week, speaking about America’s treatment of Black men: “We keep loving this country and this country doesn’t love us back.”

For Pete Hamill

I predict that the “word of the year” for 2021 will be “triage,” pronounced: tree·aazh. And that’s no small claim considering that the word for 2020 hasn’t come out yet — and here I am betting on 2021.

As you might know, every year the major dictionary companies pick a “word of the year” because they can’t find a word in their book to say what they need to say — so they invent a word, add it to their dictionary, and share it with others.

It’s an extraordinary event really because a word is being born before our eyes; on a global scale, the human race is given greater competency to speak about what it needs to stay alive — if only by a word.

For 2019, the Oxford Dictionaries chose as their word of the year “climate emergency.” They said it referred to a “situation in which urgent action is required to reduce or halt climate change and avoid potentially irreversible environmental damage resulting from it.”

They could not find the sentiment in their book so they created “climate emergency” to allow the human tongue to speak with greater confidence about, again, what it needs to stay alive.

For 2019, Merriam-Webster chose “they.” You might say, hey, “they” is already in the dictionary! But Merriam-Webster said no, the company was now using it as a singular to refer to a person whose gender identity is “nonbinary.”

A deeply profound statement. A “he” can now be a they and a they can be a “she.” And a “they” can be any other expression of gendered-being.

And yet all the grammar books, all the lessons we learned growing up about “number” say you can’t refer to more than one person as a he (or a she). You have to say they. And you can’t refer to one person as they; they are more than one — a rule that religions disregard.

Through their choice, Merriam-Webster changed the way we speak about identity. They saw using “they” instead of “he” as a matter of justice for it takes into account the needs of people whose identity stood in a “no-man’s” land.

Those are two instances of the word of the year for 2019 by two great dictionary companies; now we await 2020.

But I suggest, as we do, that we pay attention to the word I chose for 2021: triage — and, yes, it is in the dictionary.

By 2021, “triage” will be seated deeply in the conscious of every American — and every other soul affected by the coronavirus — because it means a group or committee will be making decisions about who will live and who will die by culling the herd.

That is, part of the population will be denied the resources it needs to stay alive — capitalist ideology on steroids — because those resources just aren’t there.

Webster’s Third International says triage is: 1 Brit a: the process of grading marketable produce; b: the lowest grade of coffee berries consisting of broken material 2: the sorting and first-aid treatment of battle casualties in collecting stations at the front before their evacuation in hospitals to the rear.

The last is what most people are familiar with. Fans of the TV series M*A*S*H know all about it. In the show’s 122nd episode, “Margaret’s Marriage,” Chief Nurse Major Margaret Houlihan performs pre-op triage in a wedding dress!

And with “triage” we find ourselves once again in the field of economics because we’re talking about the value of some thing or some one as opposed to the value of some other thing or some other one. It’s “Antiques Roadshow” with people being appraised.

Triage says there’s only so much to go around and too many in need, so some will be sent to the desert to let the birds of the air have their say.

It’s very much related to the concept of “the value of a statistical life” (VSL), which is a measure of whose life is valuable — calculated by how much society is willing to spend to keep a person (or group of persons) alive. Triage says some are not worth the price; they cost too much.

You can see how all this relates to the distribution of the vaccine we have been promised to inoculate ourselves against COVID-19. It’s no small thing.

What if the vaccine is “strong enough” so a person can go to the mall any time he wants, can wade into the thickest crowds at the shore, can shop day or night without the slightest fear of catching anything — no mask! You want to be first in line?

If you read, or listen to, or watch, any of the major news sources in the country (world) today, there is considerable discussion about how fair the upcoming distribution system will be. The word transparency keeps cropping up; nobody wants to be cheated unfairly.

What’s troubling is that the matter is already before us. On July 25, Nicole Chavez and Kay Jones reported for CNN in an article “A Texas hospital overwhelmed by the coronavirus may send some patients home to die.”

“May send some patients home to die” means triage, the desert, the birds of the air having their say.

The medical staff at Starr County Memorial Hospital in Rio Grande City — located on the United State-Mexico border — said they couldn’t take it anymore, they were out of gas, nothing was left in the cupboard, they were sending people home, to die, in some cases alone.

In a Facebook post, Starr County Judge Eloy Vera said with wistful sadness, “Unfortunately, Starr County Memorial Hospital has limited resources and our doctors are going to have to decide who receives treatment, and who is sent home to die by their loved ones. This is what we did not want our community to experience.”

Later she said, “Our backs are against the wall. We are literally in a life and death situation.”

Committees were being set up at Starr County Memorial Hospital to decide who should go home. Starr County? I keep thinking of Star Chamber.

Who then should get the vaccine first? Doctors, nurses, and all their assistants, who keep bodies lined-up in hospital hallways, alive? There seems to be universal agreement they should get the shots first.

What about “vulnerable populations?” Are they next? Recent epidemiological data say the poor, African Americans, and Latinos are the worst hit by COVID-19. Should not they, our poor, our black, and our Brown citizens be next in line?

What about the agèd? Those 75 and over the virus blows through like a locomotive. Should not they be next? But some will say: Those old fogies had their day; let’s focus on younger souls to give them a shot at life.

These are the kinds of variables that comprise America’s (the world’s) value of a statistical life index today and will determine who will be culled from the herd.

And if Miss Corona rages even more so this coming fall and winter — as is universally agreed she will — there will not be enough beds to go around. Who should be the first to get — as they used to say in vaudeville — the hook?

Footnote: Hospice teams will be stretched so thin, they too will send folks to the desert to die, some alone and some spiraling in wonderment as the birds of the air circle above. I can hear them now: “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave/ O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

And, if it does, they’re saying, why ain’t it waving for me?

— National Archives and Records Administration

Dr. Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech during the Aug. 28, 1963 March on Washington. Four months earlier, he had written in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”: “When these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream.”

Anyone living in the United States who’s read a newspaper or been near a television in the past two months is well aware of the persistent and wide-scale chants for “systemic change” in American society, most recently instigated by the violence the American justice system has perpetrated against Black Americans.

A dozen years ago, people were calling for change in the way Washington worked; now, as biological and racial viruses eat at us, people are calling for fundamental changes in the way America works — systemic problems require systemic change.

I understand what people mean when they say “systemic” but I find the term too generic and linear so I use “structural.” Structural better gets at the depth of the problems at hand.

For example, we can talk about “structural violence,” that is, the violence that results from the way American institutions are structured whereby greater value is assigned to some while the needs of others are minimized or dismissed altogether. Whites are rated over Blacks, men over women, straights over gays, Christians over Muslims and Jews, and people over planet Earth.

And the system’s distribution outlets are set up to provide bounty for those assessed greater and to insure that the lesser get less: of pay, compensation, and all the goods and services that meet a person’s — to channel Abraham Maslow — “safety needs.”

We all know that the resources a person has available deeply affect his peace of mind. How sad then that a land of “amber waves of grain,” as Jordan Weissmann pointed out in a 2013 article in The Atlantic, is a system “Where the Poor Don’t Get Holidays Off.” Nor healthcare.

The ideology that underlies, and is used to justify, such a distribution is best described as “deservingness.” The rich say they deserve what they got because they worked hard for it, and those in power say they earned it — and most believe they did it on their own.

The Russian philosopher-geographer Peter Kropotkin found such a claim absurd. In his famed essay “Our Riches” he emphasized, “There is not even a thought, or an invention, which is not common property”; everybody rises on the shoulders of others.

He said there were, “Thousands of inventors, known and unknown ... [who] died in poverty ... Thousands of writers, of poets, of scholars, [who] labored to increase knowledge, to dissipate error, and to create that atmosphere of scientific thought, without which the marvels of our century could never have appeared.”

One of the most disturbing aspects of a “desserts-based” economy is that it inflicts debilitating lifestyles on millions and produces a stream of poor who never get out from under misery.

What do we tell a woman — who takes three buses to work each morning and three back home after chipping the morning toast off the toilets of the rich — when she overhears her “client” talking about a four-million-dollar house she just bought in Malibu and the thousand dollars her husband spent on dinner the night before?

And what do we tell a farm worker, who gave his life to a farm for 40 years, and was sent to retire without a penny of pension?

These souls might not understand the subtleties of Keynesian economics but are well aware of the resentment they feel about division.

As we continue to wrangle over who America is and will be, the first thing we need to do is stop the indiscriminate, random, violation of the human rights of American citizens sanctioned by law enforcement’s “‘I Can’t Breathe’ Handbook.”

What is needed is not a defunding of police but a serious and intensely systematic re-evaluation of the meaning of “protect and serve.” John Jay College of Criminal Justice Professor David Kennedy says cops need to take a Hippocratic Oath.

And those cops who suffocate, or shoot in the back, unarmed Black men, are not a few bad apples because the barrel has rotted. Conspiratorialists say the methods police use to screen out racist applicants are not designed to weed out bad apples but to screen them in so their violence can “teach a lesson” to those intent on challenging the system.

And it’s paramount to keep in mind that racists do not simply despise people of color, they denigrate all categories of people they deem less: They say women are inferior to men, they laugh at gays, they heap scorn on Jews.

Thus America’s Personal Value Index (PVI) not only defines Black people as less than whites but pays women on the job 81 cents for every dollar a man makes; it mocks LGBTQs who seek a seat at the table; and treats Jews like, well, what a sad night in American history it was when neo-Nazi sieg-heiling torch-carrying confederates in Charlottesville chanted “blut und boden” and “Jews will not replace us.”

Even the president of the United States got in on the act when he applied the PVI to the people of Mexico, calling them a band of drugged-up criminogenic rapists.

Any time we use words like “more” and “less,” “deserving” and “undeserving,” “value” and “worth,” we situate ourselves in the field of economics — which is essentially a science of human enjoyment. Economics measures the means we use to find enjoyment in life and who we allow to share in it.

Of course that a nation assigns value to people is not an oddity. We all do it in every relationship we have so we might get a better read on the “other.” You’re assessing me right now while you’re reading this.

But the ultimate purpose of assessment is to improve relationships, to relieve people of stress, and to allow the least to sit at table with the rest of us.

You can understand how all this turmoil is creating problems for “the American Dream.” James Truslow Adams was the first to use “American Dream” in the way we understand it today, in his 1931 “The Epic of America” where he describes America like a “city on a hill.”

Adams said the American Dream was a land “in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement.”

He said a new car and a promotion at work are fine but the essence of the dream is when “each man and each woman [is] able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and [are] recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.”

Sigmund Freud was a specialist in dreams; he said people dream to get something reality will not allow them during the day; dreams fulfill wishes.

Thus at 3 a.m. a slumbering soul needs to go to the bathroom but instead dreams of a waterfall flowing into a beautiful ravine, and feels relief — but soon awakens and has to run to the loo; the dream accomplished nothing.

Freud also saw there was another level of consciousness that, instead of supporting dreams being fulfilled, rises up against it like a confederate nation.

Last month, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the findings of a study of how much Medicare and Medicaid spend on seniors who get sick with the virus. The data say: If you’re Black and poor, you get the virus faster, you go to the hospital sooner, you say hello to death long before your white and well-off comrades do.

How do we deal with a system that’s ambushing the American Dream for all? How you respond to those 14 words says how just a person you are.

Thank you, Class of 2020, for offering me the opportunity to speak to you on this most important day. You climbed a mountain, you reached the peak, and here you sit before me, victors all; I’m thrilled to share your joy.

Your next step will be to take a short breath and consider the mountains to come.

That might involve school, a job, or blocking out extended time to ponder what you’re meant to do in life, to find your calling as they say. I do not mean to be exclusive but I have a special place in my heart for those called to be poets and contemplatives.

When I think of life as climbing mountains, the “Purgatorio” of Dante Alighieri comes to mind, the second part of the “Divine Comedy.”

In grand poetic style, Dante says the struggle a person faces to find his true self involves not one but seven mountains. And each mountain represents a type of suffering we must go through to rid ourselves of the sin, vices, peccadillos, the falsity that keeps us confined.

Like the Desert Fathers, he called those barriers-to-selfhood “seven deadly sins,” each an attitude-cum-behavior that turns us against ourselves.

Among them are: being envious of what other people have or do (envy); acting with rage in our interactions with others (wrath); seeking more than we need in life (greed); and using power like a god to protect our possessions (pride).

In his classic work “Fear and Trembling,” the Danish philosopher-poet Søren Kierkegaard says the purgatory experience involves a scrubbing away of the rust of falsity so a person can be “that self which one truly is.” Refusing to do so, he says, is a sign of despair.

The 20th-Century psychoanalyst Carl Rogers highlighted Kierkegaard’s assessment this way: (1) the most common form of despair is “not choosing,” that is, avoiding the risk “to be oneself;” and (2) the most deadly form of despair is to choose to become someone else.

Kierkegaard and Rogers both saw that scaling the mountains to become one’s true self is the greatest responsibility we have to ourselves.

And Dante said that, when a person faces up to the transformations purgatory exacts, he becomes a spiritual being, that is, he lives with an equanimity close to happiness.

And “spiritual” does not mean something wispy and ethereal but the life of a body grounded in purpose, a body in communion with others, when political and economic realities align with justice.

In the third part of his trilogy, the “Paradiso,” Dante says no one gets to heaven who’s at odds with himself; heaven is for those who answer their calling. Such people treat others like they want to be treated, what Christians call being “Christ-like.”

The Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926), forever interested in human growth, saw what Dante, Kierkegaard, and Rogers saw but through a different lens.

He said, as he walked down the street, he could see in people’s faces “unlived lines,” signs of emptiness.

In the 12th poem of Book II of “The Book of Hours,” he says every forfitter’s “true face never speaks” wrapped as it is in a mask, a mask that thickens as faces are put on and cast off like old clothes.

“Somewhere there must be storehouses,” Rilke says, “where all these lives are laid away/like suits of armor or old carriages/or clothes hanging limply on the walls./Maybe all the paths lead there/to the repository of unlived things.”

Lived things have no falsity because they reflect the realized dreams Sigmund Freud spoke of in “The Interpretation of Dreams.”

We hardly hear the word “calling” anymore because long ago the Catholic Church took it over and limited its meaning to when a person becomes a priest or a nun — and, of course, the only voice worth hearing is the voice of God. Thus, all the revelations that come from the conversations we have with ourselves, deep in consciousness, are written off.

And, when we say “having a conversation with ourselves,” who is that other voice? Who are we talking to? Whatever you say, it’s certain that that voice, at its deepest, offers radical insights into our destiny and, like an empathetic friend, encourages us to persevere.

In “The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life,” the noted New York Times columnist David Brooks says he is well aware of the pains of purgatory, and that there’s always another mountain.

And he may have added a new sin to Dante’s list: that of being an abstracted person, living an unlived life in personal relationships with others.

Brooks says that, although he achieved great fame as a journalist and thinker, the climb up the mountain-of-success rendered him “aloof, invulnerable and uncommunicative, at least when it came to my private life.” Sounding like Augustine of Hippo he confesses, “I sidestepped the responsibilities of relationship.

Dear Graduates, I beg your pardon for raising such weighty issues as you, your family, and friends are aching to go out for a bite and hoist a glass in your honor.

Take your time, enjoy the day, these questions will be here tomorrow: Who will you be in public? Who will you be in private? Will you live an unlived life and sport a face of unlived lines?

And remember, only Walt Whitman-like candor can move a person from purgatory home.

The rock musician Eddie Money used to sing a line: “I’ve got two tickets to paradise.”

I’ve got two too, one for me and the other for, well, what are you doing for the rest of your life?

Years ago, when I was with students nearly every day of the week, I often enough encountered a soul who said he wanted to be a writer, and I was thrilled.

For each of these tyros, I had a set of questions, made a recommendation, and then gave a small assignment to test their resolve.

The first thing I asked was: Did you write today? And (almost) always the answer came back no.

Then I’d ask: Well, did you write this week? Again (almost) always a no.

And finally I’d say: Is there something you’re deeply passionate about that you’d like to explore and share your findings with the rest of the world via pen and pad?

The response was, as some stand-up comics say, crickets.

The recommendation I made — and still do when the occasion arises — was that the aspirant read the first three sentences of James Joyce’s “Araby,” one of 15 stories in his beloved “Dubliners” collection.

“Araby” starts: “North Richmond Street, being blind, was a quiet street except at the hour when the Christian Brothers’ School set the boys free. An uninhabited house of two storeys stood at the blind end, detached from its neighbours in a square ground. The other houses of the street, conscious of decent lives within them, gazed at one another with brown imperturbable faces.”

In 61 words, Joyce paints the backdrop for a movie set. In three sentences he presents an endless flood of questions. Why was the street quiet? Did the boys from the Christian Brothers’ school live on the street or were they passing through? Were they loud and noisy and disturbing of the “decent lives?” Why was a house empty and what were the personalities of those living in “brown imperturbable faces?”

The assignment I gave to my tyro was to survey the space that extends from the period of each sentence to the first word of the next, and then to wade into that space the way he might wade into a pool. And once there, to listen.

When the tyros heard that, their faces twisted as if they had just taken a shot of vinegar.

But I’m here today not to praise Joyce — he has his legions — but to call attention to Joseph Mitchell, an American writer, a New York writer, an ethnographer, and lover of Joyce, whose stories, though different from his, are quite their equal. And Joyce is considered tops.

Early on Mitchell wrote for The New York Herald Tribune and then The New York World-Telegram. A collection of the stories that appeared in those papers comprise “My Ears are Bent,” which Sheridan House came out with in 1938. Mitchell’s ears were always bent to listen.

Readers know Mitchell of course, and collectors keep their eyes peeled for special editions of his work. A first edition cloth copy with dust jacket in near fine condition of “My Ears are Bent” is listed on AbeBooks for $4,500 ($10 first class shipping), The publication price was $2.50.

But the biggest change in Mitchell’s life came when Harold Ross, the co-founder and editor-in-chief of The New Yorker took him on in 1938 to produce art with pen and pad. Though the magazine’s prospectus said it would not cater to “the old lady in Dubuque,” Ross wanted people who wrote chatty, informal, contemporary (hip) pieces.

When Mitchell’s work started appearing, people in every quarter of the country took to him — his picture was on the side of delivery trucks — they loved the way he told stories. And he had such a penchant for the lost and lonely of the world, those whose soul you have to look deep down into to find out who they are.

Some writers referred to them as “little people,” which set Mitchell on fire. In the intro to his 1943 “McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon” collection, he says: “Many writers have recently got in the habit of referring to [those people] as the ‘little people.’ I regard this phrase as patronizing and repulsive. There are no little people in this book. They are as big as you are, whoever you are.”

And he lived that way, a radical who became the voice of the voiceless — which people say contributed to his persistent sadness.

They also say “Mr. Hunter’s Grave,” which appeared in September 1956, is his best work. Mitchell tells how, while visiting a cemetery on the south shore of Staten Island, he met a Mr. George Hunter, an 87-year-old trustee of an African-American church on the island’s Sandy Ground community. Hunter was the last of a breed of black oystermen who worked the island’s shoals at the end of the 19th Century.

As the pair walked past the cemetery’s stones, they came upon the graves of Mr. Hunter’s two wives, and then Mr. Hunter pointed to where he would rest. Mitchell paints him with such immediacy and fine strokes that we’re led to another world.

But there are two things you need to know about Mitchell. The first is that some of the people he wrote about were creations or composites of people he met, which his editor knew about and even allowed with other writers on the staff — but Mitchell still catches the brunt of critical scorn.

The other thing you need to know about Mitchell is that, once he finished his famed “Joe Gould’s Secret” in 1964, he produced nothing else for the magazine. For 31 years and six months, he showed up at work every day, closed the door to his office until lunchtime; back from lunch, he closed the door until it was time to go home — nada. He died in 1996.

He told a reporter, “I can't seem to get anything finished anymore. The hideous state the world is in just defeats the kind of writing I used to do.”

“The Rivermen,” which appeared in March 1959, is one of Mitchell’s meditations on the gift of life.

It begins, “I often feel drawn to the Hudson River, and I have spent a lot of time through the years poking around the part of it that flows past the city. I never get tired of looking at it; it hypnotizes me. I like to look at it in midsummer, when it is warm and dirty and drowsy, and I like to look at it in January, when it is carrying ice.

“I like to look at it when it is stirred up, when a northeast wind is blowing and a strong tide is running — a new-moon tide or a full-moon tide — and I like to look at it when it is slack. It is exciting to me on weekdays, when it is crowded with ocean craft, harbor craft, and river craft, but it is the river itself that draws me, and not the shipping, and I guess I like it best on Sundays, when there are lulls as long as a half an hour, during which ... nothing moves upon it, not even a ferry, not even a tug, and it becomes as hushed and dark and secret and remote and unreal as a river in a dream.”

All the stories that appeared in The New Yorker can be found in “Up in the Old Hotel,” a 718-page omnibus of endless treasure that’s still in print and affordable.

His colleague at the magazine, Roger Angell, used to say Mitchell’s stories stand “firmly and cleanly in your mind, like Shaker furniture.”

That’s because he was a Shaker, he was a man who heard the voice of God in everyone he met.

— Photo from the Office of the President of the United States

The day after Donald Trump’s inauguration on Jan. 20, 2017, his press secretary claimed Trump drew the largest audience to ever witness an inauguration, although photographs showed otherwise.

One of the most celebrated experiments in the field of social psychology is a series of studies the Polish-born psychologist Solomon Asch began conducting in 1951 with 123 students at Swarthmore College.

The scientific record lists this body of work as the “Asch conformity experiments” or “the Asch paradigm.” The paradigm spawned generations of great psychologists — the late Stanley Milgram among them — who sought to understand how deep a person’s ethical convictions run.

For example, if someone came along and told you to harm somebody else, would you do it? What if a lot of people said so? Would economics be a factor?

Anyone who’s been to college and taken Psych 101 — or found out otherwise — knows Asch’s work, unless they were sleeping in class or are simply lazy.

At Swarthmore, Asch wanted to see if a person would tell the truth if a group put pressure on him to say otherwise — psychological instigation of the upperworst kind.

Of course, any time a person caves to the will of others, as research shows, perceptions change, the person weighs and measures things from an angle of anger and defeat.

But let’s not blame the eyes for misperception, the eyes are directed by the managerial-mind to gather data for its ends, which requires denying the physical world and blowing with the wind.

But we can’t blame the mind either; the mind works for the heart, the libidinous heart, which uses the mind to calculate pay-off — the basis of all religion.

When I first read Asch’s studies I wanted to know if a person would actually sell himself out by sacrificing his most treasured tool: an accurate-recording pair of eyes.

I also wanted to know how a person handles such “treason” because it results in such an erosion of one’s ethical core and moral fortitude.

Asch had eight students sit around a table who were shown two cards, one after the other.

On the first card, there was a single straight line. The second card had three straight lines of different lengths — one of which was exactly the same as the line on card one. Everybody was asked to say which line on card two was the same as the line on card one.

But seven of the subjects were “in on” the experiment, that is, the researchers told them beforehand to pick the wrong line on card two; they wanted to see if a person would buckle from pressure.

Incidentally, the assignment was a no-brainer, a child could pick out the line.

When it came to the “dupe’s” turn, he kept looking at the lines on card two thinking about what seven others just said.

Pressed with a decision, his calculator ran up and down the list of pay-offs: what to do, what to do — I can hear the music of Final Jeopardy!

For those needing a more concrete example, it’s this: There’s an apple. You see the apple and gush: oh, what a beautiful apple!

Then a group comes along and says: Beautiful nothing! That’s not an apple, it’s a baseball. And ticktock your ethical computer starts churning: Apple or baseball? Baseball or apple? What to do, what to do.

When a person says baseball — as his eyes are looking at an apple and reporting to the mind “apple” — the mind has already intervened and translated the data politically.

If you’ve ever studied the origin of numbers, you know why 1 became 1 and not a 2, or one-and-a-half. The species had come to an agreement that 1 would be 1, always, a hair no more a hair no less. 1 is 1.

One way to make sense of the militia groups that barged into the State Capitol of Michigan earlier this month armed with weapons of war, is that they were announcing to America 1 is no longer 1, and they had the means to prove it.

But, anyone who’s worked in a bureaucracy or mercantile corporation knows that such “proof” exists everywhere. The lead paper on the subject is “Hierarchy-induced conformity without an AK-47.” Workers on the lower rungs of organizations say 1 is not 1 all the time to save their jobs.

It reminds me of the Roman Catholic poet John of the Cross, a reformer who called for religious orders to return to the simplicity of Jesus.

Church officials didn’t like what he was saying so, on December 2, 1577, they sent minions to kidnap John and lock him in a monastery in Toledo, Spain. Art critics say you can see the building in El Greco’s “View of Toledo.”

John was put in a 10-by-6-foot cell with a sliver of light coming through a wall. On Fridays, the “administration” brought him to the dining room and knelt him before the monks. One by one, the men took up a whip and whipped John’s back while the rest kept eating. Criminologists call it preventive deterrence.

I’ve read several accounts of this event and nowhere does it say a single monk stood up and said: I will not do it! What would be the pay-off?

And then comes White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer, meeting journalists on January 21, 2017, the day after Donald Trump was sworn in, claiming Trump drew “the largest audience to ever witness an inauguration, period.” Every photo taken showed the contrary.

Spicer said “PERIOD” with such a don’t-ever-challenge-me bang that he was saying 1 is no longer 1. The hammer of deceit had fallen on the anvil of truth.

I felt like I was one of Asch’s subjects sitting around the table at Swarthmore having just heard seven souls lie about what we all were seeing before our eyes.

If, as some say, a lot of people in America are angry these days, I say it’s because of the guilt they suffer from having sold their moral core like a bag of peanuts at a ball game.

Location:

For years, I taught a course at the Voorheesville Public Library called “Writing Personal History for Family, Friends, and Posterity.”

The group met once a month, sometimes twice, and around Christmas one year we sponsored a dinner-reading in the library’s community room. On neatly-arranged tables, we dressed the white linen cloth with pots of red poinsettia; everything looked grand, dinner buzzed with happiness.

After dessert and coffee, each writer got up and read a favorite story, mindful of the gift of those who came.

In 2015, the group came out with a book called “Tangled Roots: A Collection of Life Stories” that I edited and wrote a preface for. The stories are great.

Each contributor — there are nine — offered touching vignettes about how they came to be the person they were; who helped along the way; and who, in the words of the Geneva Bible, was a “Pricke in the fleshe.”

But the stories are not about thorns; they’re celebrations of life despite the thorns.

When people in our community referred to us as a “memoir” group, I told them right away that we were not a memoir-writing group but a writing-personal-history group and that the “history” part means a chronicler has to adhere to certain facts: names, places, who did what to whom, and how the “whom” fared afterward. It requires a discipline that calls memory to account.

I have looked into the memoir genre for some time — there are endless books, courses, and seminars on how to do it. I just searched “memoir-writing” on Amazon and more than 20 offerings came up on the first page — “how-to” after “how-to” after “how-to.”

There’s no need for names but some memoirists “hawk” their memoir-writing-tactics like aluminum siding. That might be too harsh a judgment but I get the sense a lot of them want to be fiction writers. Some have pushed the envelope so far in that direction that they’ve been called on the carpet for fiddling with the truth.

For them, it seems that everyday life lacks the juice or heft — Lorca’s duende — to interest family, friends, and posterity. And many forget that personal history is about the people around us, that we’re just part of the picture. We do not “own” our self.

When my late friend and great writer William Herrick (a determinedly-interesting person) started to write his autobiography, he ran into trouble right away. “Facts” clashed with his memory.

On more than one occasion, the former kid from Brooklyn told me that, during the summer when he was young, he went to live at the socialist/anarchist Sunrise Cooperative Farm in Saginaw Valley, Michigan. He said he met Emma Goldman there; no, he said he sat on her lap and fondled her, for our purposes here, unmentionables.

But when Bill started collecting data, he found that Goldman was out of the country then, having been deported to Russia (on the good ship “Buford” with 248 other souls) by the United States government.

He told me he was switching from autobiography to memoir because the rules were less demanding. Parenthetically, he said he began to wonder: If not Emma’s lap, then whose? Maybe there was no lap? Maybe no unmentionables!

What he finally did say about his life can be found in his head-turning “Jumping the Line: The Adventures and Misadventures of an American Radical” published by the University of Wisconsin in 1998. It has ’tude.

The “American Radical” part is when Bill went to Spain in 1936 to help Spain’s indigenous communities fight Franco’s fascist invasion. He wasn’t typing memos in an office, he had a gun, he was out in the field with the Abraham Lincoln Battalion listening to bullets whizz by — one of which caught him in the neck.

The doctors said, if they tried to get it out, he would die, so the bullet was with Bill on his deathbed. His wonderfully-enlightened supportive wife, Jeannette, used to say the only thing she wanted when her man died was the bullet in his neck.

Former Voorheesville librarian Suzanne Fisher — one of 27 librarians in the country singled out by The New York Times for its (distinguished) Librarian Award in 2005 — and I arranged to bring Bill to Voorheesville to talk about Spain.

He read a passage from his celebrated book on the war, “Hermanos!” It’s catalogued as fiction but Bill said it’s all true.

While he was in the hospital, he said, he confided in a nurse who then “ratted” on him to the commanding Stalinist wing of the revolution. He was escorted from the hospital to a church basement where members of the wing, the GPU, brought a half-starved Spanish boy before him and said, if he didn’t retract what he told the nurse, they would blow the kid’s brains out.

Bill said no way, and they blew the kid’s brains out.

They did this a second time with another emaciated soul and, when Bill refused again, the boy fell to the floor like a heap of wet canvas.

It happened a third time with a young girl and she was murdered too.

As Bill read about this sad traumatic period in his life, his eyes welled with tears. He told the crowd that, even after 50 years, he could not forgive himself for being righteous — he could have saved lives — and that his guilt would stay with the bullet.

In his writings and interviews later on, he spoke of the internecine warfare that took place among the leftist divisions in Spain, in some cases bullet for bullet worse than Franco.

What Herrick saw was what Orwell wrote about in “Homage to Catalonia,” that the Communist- and Stalinist-based factions fought against the grassroots collective efforts of the Republicans. They especially despised anarchists.

As we all live like Carthusians these days, I’ve heard that some older folk pace the kitchen floor wondering when dinner will be served, hoping maybe things’ll go better tomorrow.

I have a suggestion for them, and every other soul their age, and that’s to sit down at the kitchen table with pen and pad — asap — and write a paragraph of their personal history they would like the world to know about.

And from there go to paragraph two.

When a soul takes time to reach paragraphs three, four, and five, and beyond, it sees that it’s engaged in a discipline of solitude that diminishes the pain of seclusion.

Everyone must then take their finished story — it might be only a page — and put it in the metal box where deeds and similar papers are kept.

And then begin on story two.

Imagine a granddaughter 50 years from now coming upon her grandfather writing about his childhood 50 years before — the span of 100 years — explaining how he came to be who he was. What a sense of roots!

All I can think of is the prophet Isaiah (11:10) speaking about the “root of Jesse,” saying his grounding would serve as a “banner” for all the world to turn to for guidance, a rootedness the Scripture adds, that rewards such souls with a glorious resting place.

I think that’s what my Voorheesville group was striving for, to be a banner to which family, friends, and posterity could turn for guidance and maybe help a soul along the way untangle itself from roots that deny it happiness.