In many cultures throughout the ages, there are periods of time when the boundary line between this world and the “other” grows thin and those on the other crossover to visit us.

Often described as liminal, these times are linked to seasonal changes as in the fall when the darker half of the year (winter) is on its way or in spring when new light is coming back. The interplay of light and darkness upsets the way things are.

When the fall harvest season was ending and brought winter’s light, the ancient Irish celebrated the Gaelic festival of Samhain. They called it the time of the “new fire.”

The late great 20th-Century anthropologist J. G. Frazer said, “In Ireland on the evening before Samhain a new fire was kindled which signaled the beginning of a new year. It was hoped the new fire would serve as a comforting light in the darkness to come.”

Indeed inhabitants of many villages collected sticks charred by the new fire, hoping their presence at home would prevent house and family alike from being struck by lightening or shaken by some other catastrophe.

The festival of Samhain was celebrated on Nov. 1 and its vigil the night before was known as All Hallow’s Eve or Hallowe’en, which means hallowed evening or holy evening; waiting for the visitors to arrive was a holy time.

Of course, we can see the connection between Halloween these days and the ancient festival especially after the Christian Church baptized the pagan rites and called them Allhallowtide. The triduum comprised All Saints’ Eve (Halloween), All Saints’ Day (All Hallows), and All Souls Day stretching from Oct. 31 to Nov. 2.

In his unsurpassable-classic “The Golden Bough” — the full 12 volumes not the single that college students were once familiar with — Frazer says Allhallowtide is the “time of year when the souls of the departed were supposed to revisit their old homes in order to warm themselves with the good cheer provided for them in the kitchen or the parlour by their affectionate kinfolk.”

The early winter winds drove “the poor shivering hungry ghosts from the bare fields and the leafless woodlands to the shelter of the cottage with its familiar fireside.” Some folks approached the visitation with fear because spirits of any ilk could come their way, but others saw the fading light as a time for hospitality, for welcoming their loved ones back among the living.

To provide sustenance for the alien souls, the residents of towns in southern Germany and Austria baked “soul cakes” or “souls” on All Souls Day (many of which they enjoyed while waiting).

In Shropshire, England, even into the 20th Century, on All Saints’ Day members of the community went house to house “souling” — poor people in particular, singing “A soul-cake, a soul-cake,/ Have mercy on all Christian souls for a soul-cake.”

It was hoped that neighbors would provide a cake, some apples, maybe a bit of change and, for the accompanying adults, a sip or two of new ale. Charlotte Sophia Burne and Georgina F. Jackson in their classic “Shropshire Folk-lore” published in 1883 recorded instances of homes whose “liberal housewives … would provide as many [soul-cakes] as a clothes-basket full.”

In the Tyrol, Frazer says, the folk also made “soul-lights.” These were lit and placed on the hearth on All Souls’ Eve so that “poor souls, escaped from the fires of Purgatory, may smear melted grease on their burns and so alleviate their pangs.”

Over time numerous permutations of the earliest Samhain rites developed in different countries, some varying even by locality. Toward the end of the 19th Century in Europe, “souling” was still alive with people going from house to house in search of cakes filled with soul. Souling then morphed into guising or mumming, when children disguised themselves in costume and offered songs, poetry, and jokes — instead of prayer — in hopes of receiving food or coin for their dramatics.

Folklorists say the Scots in masquerade visited neighboring homes carrying lanterns made from scooped-out turnips not only to light the darkened way but also to turn away potentially-threatening ghosts.

When immigrants came to North America, this aspect of the festival morphed into lit pumpkins and trick-or-treating but older folks will recall that families came together to eat and drink and watch the kids play fun-filled games like ducking for apples. In County Kerry and parts of Newfoundland and Labrador, Halloween is still called “Snap-Apple Time.”

Those familiar gatherings have all but ceased. Halloween has been reduced to costumed kids trudging door to door expecting treats — or else. Long forgotten is Allhallotide to honor the memory of the dead. Journalist Lesley Bannatyne who has given considerable thought to the holiday, says, “The otherworldly elements of Halloween have moved into the realm of fantasy, satire, and entertainment.”

She’s right but does not mention that no one has to accede to such debasement. It’s possible to honor the souls we once knew by going out to visit them, and our efforts are not limited to formal hallowed eves.

Writers in a class at the Voorheesville Public Library called “Writing Personal History for Family, Friends, and Posterity” do not wait for liminal times when the past can meet the present. They thin the boundary themselves and enter the world of the other with enthusiasm.

That is, they honor the long-dead of their families with stories filled with love, humor, and truth. One soul has sung of a mother who lost direction — no one figured out why — so she and her family had to find ways to accept the ensuing senselessness.

Another writer told of his Italian-American family from Niagara Falls who never stopped talking when they came together, except in the case of a mother’s son who separated from the family only to die, years later, of AIDS. The writer was still having a hard time understanding why the family failed to wrap its collective arms around his brother.

Still, another writer spoke of a bell tower in her native town in Italy that through its hourly tolls reminded every resident to cherish the here and now.

All these writers dared to step across the boundary and speak to the departed with questions based in love and respect even when filled with pain.

These memorists celebrate their own All Saints Day, their own All Souls Day, their own Halloween; they address the departed, especially those who cannot handle the truth, and in doing so render peace for all involved.

Happy Allhallowtide.

Location:

Do you use irony in your conversations? It’s when you say the opposite of what you mean.

For example, on vacation you get to your room at the hotel and look out the window and there, 30 feet from your nose, is a solid brick wall. You say: Oh, look: Another great view of America!

To mask your disappointment — let’s call it that — you say the opposite of what you mean, the literary lexicons say for “humorous or emphatic effect.”

Anyone hearing you knows you did not get what you wanted or hoped for. You were looking for a scenic view and got industrial brick.

But I’m betting that understanding the nature and purpose of irony in your life is not on your bucket list as it’s not on the list of many others.

But that’s a poor approach to reality because the pervasiveness of irony in the cultural and social institutions of America today, especially through literature and television, is adversely affecting our efforts to forge a new national identity. We don’t know what people mean.

But I should point out that irony is a two-edged sword in that it can have a freeing function while other times, like now in the United States, it has morphed into a corroding sarcastic cynicism.

In a 1987 essay on the poet John Berryman, Lewis Hyde said, as a tool, “Irony has only emergency use. Carried over time, it is the voice of the trapped who have come to enjoy their cage.” Subscribers are prisoners.

The great American writer of fiction and commanding revolutionary essays, David Foster Wallace (1962-2008) — he took his life besieged by despair — called irony tyrannical and useless “when it comes to constructing anything to replace the hypocrisies it debunks.” It lacks the power to transcend.

He points to postmodern literature’s love affair with irony but especially to television’s “cynical, irreverent, ironic, absurdist” depiction of social situations steeped in condescending mockery.

Wallace says at some point television swallowed irony whole (as well as its kin sarcasm and cynicism) and once it filtered into every channel it trained viewers “to laugh at characters’ unending put-downs of one another, to view ridicule as both the mode of social intercourse and the ultimate art-form.”

Is not the social commentary program of John Oliver (as was the case with his predecessor Jon Stewart) a savaging session?

When sharp-tongued comics Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce stepped into the arena in the 1950s, they opened the floodgates of a biting criticism that seemed perfect for the post-World War II generation. They skewered the McCarthy-reeking government and any other institution that held people down.

Over the decades, America’s institutions have taken it on the chin so often and in so many ways that an interloper like Donald Trump can come along and call The New York Times and The Washington Post purveyors of “fake news” and the FBI crooked and unreliable in serving the American people, thereby firing up a cadre of torch-bearing cynics.

That supreme generator of scorn is heralded as a savior for shielding the heapers of scorn from scorn. How can those who cherish the values of honesty and sincerity compete?

And the reason scorn, sarcasm, irony, cynicism, and the like remain “so powerful and so unsatisfying,” Wallace says, “is that an ironist is impossible to pin down. All U.S. irony is based on an implicit ‘I don’t really mean what I’m saying.’”

We have to ask ourselves whether it’s possible to get an ironist to say what he means even when someone “with the heretical gall to ask an ironist what he actually stands for,” Wallace notes, “ends up looking like an hysteric or a prig.”

The mouthing-off ironist, whether personal or corporate, sounds on the surface like a rebel but in truth is an oppressive tyrant because attention is drawn away from his needs and the needs of his neighbor, especially the less-well-off. The primary categories of reality are dismissed as fluff.

How would we ever know what anyone’s needs are when people say what they do not mean and what they mean they do not say?

A great part of the furor of the Trump supporter derives not so much from his supposed dissatisfaction with existing social institutions but from being trapped in a scorn-ridden identity that wears upon his being. He might think lashing out is a source of relief but it creates endless exhaustion for the rest of us.

And enough evidence exists that shows that those afflicted with irony-based despair soon begin to conjure up conspiratorial ghost stories laced with facts that do not exist.

Climate-change-deniers will never be convinced of a historical reality until they deal with the corrosive cynicism they suffer from based on needs not being met. And such cynicism is addictive because it provides a certain kind of neural pleasure; when you’re cutting a fellow citizen down, you feel alive.

What happens in the long run, though, is that the imagination is blunted. The tool that allows us to envision a way out of a morass such as irony, cynicism, and related deep-hole-diggers, loses its grounding.

But the imagination is critical because, as the educational philosopher Maxine Greene points out in “Releasing the Imagination,” it is our means “to invent visions of what should be and what might be in our deficient society, on the streets where we live, in our schools.” Transcendence.

It may sound strange but we must start conversing about topics that cynics have long labeled utopian. Take full-coverage-lifetime-health-care as an example. The American cynic says it cannot work even though France and Canada and a host of other nations have provided such care for their citizens for decades. They shame us.

Impractical? Practical? These words pale in comparison to the corrosiveness of cynicism. With it comes to the practical; we have to remind ourselves of what Oscar Wilde said a century ago: “A practical scheme is either a scheme that is already in existence or a scheme that could be carried out under existing conditions. But it is exactly the existing conditions that one objects to; and any scheme that could accept these conditions is wrong and foolish.”

Is it practical to suggest an annual income for every person in the United States of $100,000, students included because they work like the rest of us?

Is it practical to stipulate that anyone who makes over $1 million a year must hand over every dollar above the million-dollar mark to the national treasury? The Congressional Budget Office can figure out the details.

What about the provision of a comfortable abode for everyone? How might such a system work? And this would include home-repair and home-replacement for every U.S. resident done in by a storm, even U.S. citizens in the Virgin Islands.

We must include cynics in our discussions forward but must remind them that the agenda is about needs, the rightful needs of all. This means that cynicism must be checked at the door like they used to do with guns in the Old West.

Location:

— Photo by Luca Galuzzi - www.galuzzi.it

Stillness predominates in the Sahara, writes Paul Bowles in “Baptism of Solitude.”

In the April 14, 2017 edition of the “Independent,” an article appeared by Katie Foster called “Children as young as 13 attending ‘smartphone rehab’ as concerns grow over screen time.”

Anyone who’s lived in the United States for more than an hour knows the United Kingdom is not alone in this “fight.” There are tables in every food court in every mall in the country where four or five young adults are sitting, eyes glued to the screens of some electronic device withholding presence from their comrades.

I have long wondered what the quality of silence is like in their homes. Is there any? Do members of their family or any family have a time and place for solitude? Are periods of solitude encouraged? Do family members read books of a meditative nature that help them sort life’s plaguing details?

I am especially aware of these issues at the moment because I’m reading a book of essays by the expat American writer Paul Bowles, “Travels: Collected Writings, 1950-1993.”

Bowles died in 1999 at 81 and, though an inveterate traveler, called Tangier, Morocco his home for more than 50 years. As a person attentive to what is, he began to absorb the bare bones reality of Africa, especially the silence one finds upon entering the Sahara.

In describing that silence Bowles hints as why those addicted to media-screen realities refuse to adjust their lives to include solitude. It’d require going cold turkey.

In a piece he wrote for “Holiday” in 1953 called “Baptism of Solitude,” Bowles says that, whether a person has gone into the Sahara once or 10 times, the first thing that commands his attention is the “stillness.” In that “hard stony place ... an incredible, absolute silence prevails.”

Even in the busy marketplaces, he says, “a conscious force [exists] which [resents] the intrusion of sound.” The underlying silence is so great that noise is minimized and eventually dispersed. Even the sky at night joins in; it “never really grows dark” but remains “an intense and burning blue” as if silence will not let the pilgrim go.

Then Bowles points to an inevitable conflict. He says, once you step outside “the gate of the fort or town” you’re staying in, you either “shiver and hurry back inside the walls, or you will go on standing there and let something very peculiar happen to you.”

The French have a phrase for the latter; they call it “le baptême de solitude,” the baptism of solitude.

It’s an experience of aloneness but has nothing to do with loneliness because loneliness presumes memory. Out there in that “wholly mineral landscape lighted by stars like flares,” Bowles says, “even memory disappears.” A person doesn’t know if he’s coming or going.

Then a strange interior “reintegration” occurs and “you have the choice of fighting against it, and insisting on remaining the person you have always been, or letting it take its course.” It’s the scriptural paradox: Unless the grain of wheat dies, it will not have life but, if it accedes to reality, it will live and multiply.

Bowles is speaking about the Sahara, of course, but he’s also speaking about the experience of solitude and silence anywhere. When a person encounters silence he’s not “quite the same as when he came.”

William Wadsworth, the poet, spoke of his need for this way of being. Social intercourse with friends and neighbors might be fine, he says in his famed poem “Personal Talk,” but:

Better than such discourse doth silence long,

Long, barren silence, square with my desire;

To sit without emotion, hope, or aim,

In the loved presence of my cottage-fire,

And listen to the flapping of the flame,

Or kettle whispering its faint undersong.

The Trappist monk, Thomas Merton, who was one of the 20th-Century’s champions of solitude, was more prescriptive. He said, when silence and solitude are absent from our lives, we never become the person we were meant to be. The latter requires a trip to the desert.

In his “The Silent Life,” Merton says all people “need silence and solitude in their lives to enable the deep inner voice of their own true self to be heard at least occasionally. When that inner voice is not heard, when man cannot attain to the spiritual peace that comes from becoming perfectly at one with his own true self, his life is always miserable and exhausting.”

No one can remain happy for long, he says “unless he is in contact with the springs of spiritual life which are hidden in the depths of his own soul.” He treats it as a law of nature.

How would you begin to explain such a process to one of the screen-addicted teens at the mall? One study said half the teens in the United States send 50 or more texts in a day, while one in three send more than 100; that’s 3,000 a month. The numbers seem high but the study noted as well that 15 percent of the teens surveyed send more than 200 texts a day. Twelve texts an hour?

The screen. A study by Common Sense says that, when added up, teens are logged onto a screen of some sort nearly nine hours a day, with those in the tween category logging in at six, almost as much as they sleep at night.

This oblique disregard for solitude manifests itself in how teens do homework. They have the TV on, and take breaks to text or network in some fashion. One study says three-quarters of teens listen to music while doing homework.

What can be the quality of such work? What can be the depth of thought? Maybe it’s better to ask: How much better could that person’s work be if done with greater thought and concentration, in studious solitude?

Psychologist Ester Buchholz in “The Call of Solitude” links solitude to creativity. In an article she wrote for “Psychology Today,” she says, “Research on creative and talented teenagers suggests that the most talented youngsters are those who treasure solitude.”

By delving into the depths of the unconscious, solitude helps a person “unravel problems ... figure things out ... emerge with new discoveries ... unearth original answers.”

On this point, Merton keeps hammering away. Without solitude, he says, a person is “no longer moved from within, but only from outside himself. He no longer makes decisions for himself, he lets them be made for him. He no longer acts upon the outside world. But lets it act upon him. He is propelled through life by a series of collisions with outside forces. His is no longer the life of a human being but the existence of a sentient billiard ball, a being without purpose and without any deeply valid response to reality.”

Bowles saw how sentient billiard balls begin to carom when silence is rejected. People cling to a phantasm of who they are rather than the person they are meant to be.

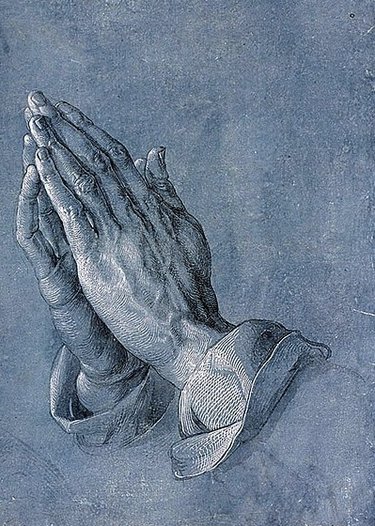

During a baseball game on television the other night, one of the players smashed a home run into the right-field stands. As he rounded third and headed home he thumped his chest with a fist, raised his two arms and pointed his index fingers to the up-above, all with great satisfaction. I took it to be a prayer of thanksgiving.

I recalled that in February of this year, when Donald Trump addressed the matter of prayer at the National Prayer Breakfast in Washington, D.C., he prayed by nicking the actor and former governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger who had taken over his “The Celebrity Apprentice” show.

Trump noted that, when he ran for President, NBC selected Schwarzenegger as host. “And we know how that turned out,” Trump said. There was laughter in the room. “The ratings went right down the tubes. It’s been a total disaster . . . And I want to just pray for Arnold, if we can, for those ratings, okay.” More laughter. Trump prayed a prayer of derision.

Then in June there was an international incident with prayer. During an AirAsia X flight from Perth, Australia to Malaysia, the plane began to shake radically and in no time was turning back. Later one of the passengers reported that the pilot suggested to all aboard that they might pray.

That would be a prayer of petition when the passengers asked the object of their prayers (sometimes it’s God) to do what it took to get them back home safely.

I have no idea whether people prayed on the plane and, if they did, what effect it had on the turnaround. Prayer is such a strange phenomenon because few people can really explain it because they cannot relate its tenets to their own psychological needs. Prayer can mean a hundred different things to a hundred different people.

When the great legal anthropologist from Berkeley, Laura Nader — the sister of Ralph — examined the functions of law in a range of societies, she discovered that law served functions other than what we usually think of, that is, doing justice. People use the law to get even with someone, to do their enemies in, to enrich themselves. The same is true for prayer, people use it for good but also for ill.

And people do pray. According to a Pew Research Study conducted in 2014 on the prayer habits in the United States, 45 percent (for Christians it’s 55 percent) of respondents said prayer helped them with making major life decisions. They said that prayer is an integral part of their identity; it helps them envision a future of meaning.

In another study conducted in 2014, San Diego State Professor Jean M. Twenge also discovered that Americans pray but, when compared to the early 1980s, multitudes reported they never said a prayer. And during the same period the number of people who said they did not believe in God had doubled.

This is due in part, perhaps, to the third of Americans under 35 who say they have no religious affiliation; in the box that asks for religion, they check “None.” These now comprise the second largest “religious group” behind evangelical Protestants.

The Nones say they do not need religion, and in many cases God, for finding their way in life and that praying is futile. Who would they pray to anyway?

Perhaps the greatest “None” of all time was the late great American comedian George Carlin who saw the praying process as laughable. Carlin said people are gross when they pray, they treat God “crudely . . . asking and pleading and begging for favors, do this, give me that.” It might be a new car, a better job, or a steamy relationship with the cashier at the 7-Eleven down the block.

Sounding like a Thomistic theologian, Carlin argued that, when people pray, their only concern is themselves. What about God!, he asked. What about his Divine Plan! Do the “beggers” [mine] want God to alter his Plan just for them?

Over the years, Carlin said, experience has taught him that prayers are answered on a 50-50 basis: People get what they want half the time; the other half, they’re ignored. He said he reached a point where he relied on the actor Joe Pesci because Pesci “looks like a guy who can get things done.” Certainly as well as God.

Centuries earlier, the German mystic and Dominican priest, Meister Eckhart (1260-1328) said — there was no Joe Pesci yet — that he knew of a form of prayer where people could always get what they wanted.

He said, “The most powerful form of prayer, and the one which can virtually gain all things and which is the worthiest work of all, is that which flows from a free mind.” What an extraordinary claim.

And then he says, “The freer the mind is, the more powerful and worthy, the more useful, praiseworthy and perfect the prayer and the work become. A free mind can achieve all things.” Another extraordinary claim. A “free mind?”

Eckhart said it’s a mind that is “untroubled and unfettered by anything.” It “has not bound its best part to any particular manner of being or devotion and . . . does not seek its own interest in anything.”

The free mind “is always immersed in God’s . . . will, having gone out of . . . its own.” It’s sort of what Carlin was saying: The beginning of prayer is detaching oneself from the ends.

In his classic work, “Contemplative Prayer,” the Trappist monk Thomas Merton says free-mind-prayer begins when we “return to the heart . . . finding [our] deepest center, awakening the profound depths of our being.”

I started speaking about prayer and especially this kind of prayer because America is undergoing a painful identity crisis manifested in our ongoing second civil war. We need the kind of prayer that will bring us to our deepest-center-self and allow us to envision a new way to be, a new national identity.

A prayer of thanksgiving, of derision, of petition will not do. We must adopt a centering form because that puts us in touch with our collective responsibilities. Without, it we can transform ourselves into a white nationalist social order where Hitler is relied on for inspiration rather than the likes of Martin Luther King Jr.

Ordinarily I do not pray but today I will. I pray that my kids and grandkids and all those I leave behind can find a way to create a nation of communities where the needs of everyone are met, where race, class, religion, and ethnic identity do not prevent anyone from access to the means of happiness.

Mine is not a prayer of derision, it’s not a laughing matter.

— “A Lonely Grave,” by Alexander Gardner, pictures Union soldiers standing near a comrade’s grave at the battlefield of Antietam, September 1862

Current Civil War: “To take away or radically modify the health-support system of 22 million Americans is an Antietam of sorts in that it strips people of the support — MRIs, medications — that keep them afloat.”

It’s a national tragedy that the United States is currently engaged in a fight over who deserves or has a right to assistance when they’re in pain or their life is threatened by some physical or emotional illness.

It’s a shame but not a surprise. It’s just the latest explosion in our current civil war, which began when the United States had its emotional breakdown several decades ago. Neurotic symptoms are everywhere.

And let’s not minimize the situation; it is a civil war. It’s not a war of bullets and bombs as in the original War of the States but a war of ideology when threats, identity-slashing labels, lying, and administrative decisions that punish and exclude, are used as assault weapons.

This kind of warfare is like the cyber warfare discussed of late, in that cyber warfare has nothing to do with bullets and bombs either and yet the hacking and invasion of people’s consciousness by electronically rifling through their private lives has deleterious consequences (for everyone).

Thus to take away or radically modify the health-support system of 22 million Americans is an Antietam of sorts in that it strips people of the support — MRIs, medications — that keep them afloat.

It’s also a stripping away of the economic security that supports emotional well-being as well as access to procedures that end pain and allow people to feel life is worth living.

The president of the United States has referred to the current measures to strip people of such supports as “mean” but to support the wellbeing of his fragile ego, has railed against the weak as unworthy for any communal consideration.

And this from a man who never cooked a meal or washed a dish, from a man whose main source of mental anguish derives from whether to install the Kohler K-4886 or Panorama Round Ceramic bidet in a football-field-size bathroom.

But keep in mind that the issue of the providing for or stripping people of health care is only a symptom. The real issue is economic and has to do with the concept and definition of worth, what or who is worth something.

The current prevailing ethic is: Some citizens are worth more than others and therefore deserve more attentive consideration. The same ethic also says: Some citizens are worth nothing and therefore deserve nothing from the collective coffers.

Worth is a political economic variable — as university professors might phrase it — because it has to do with the differential allocation and provision of resources to those whose needs are defined as worthy versus those whose needs are minimized or dismissed as unimportant.

Worthy means “worthy of our attention” and worthy of our attention means worthy of receiving that attention when we are in need. We allocate resources to those persons, groups, places, and events we say will help the nation progress.

I have a hard time trying to fathom how a person manages — practically as well as psychologically — after he has been defined as having no worth by the collective and is refused support even when his cries for help are loud.

Thus the debate over “pre-existing conditions” is a sinister, sadistic joke. It translates into: If you come to us without being sick, without something wrong, we will attend to your needs. But if you come with medical problems you are out, we will not pay for what ails you. The logic is: Come back when you get better, then we’ll help.

Who we define as worthy of the community’s attention is what constitutes the definition of “united,” whether we consider ourselves a national community or a pack of tribes pitted against each other over supposed scarce resources.

The current civil war is a tribal war fueled by the policies and projects of the financially and culturally worthy who benefit from the conflict. Amid this war the president marveled recently: Hey, the stock market keeps going up!

The guilt of “taking the life” of fellow citizens is diminished or not felt at all through the creation of relational distance. Keeping the victim out of sight.

Thus the conflicting tribes have developed their own language and cultural reference points which serve as buffers between themselves and the enemy — the person or group of lesser or no worth.

In his July 11, 2017 column in The New York Times, “How We Are Ruining America,” David Brooks addressed the issue of relational distance and some of its consequences.

He says the well-to-do, the worthy, structure exclusionary, distance-creating, worthlessness-defining strategies to protect their privilege. In terms of this kind of protectionism he says, “Members of the college-educated class have become good at making sure their children retain their privileged status.” They do this “by making sure the children of other classes have limited chances to join their ranks.”

In the past 20 years, he adds, the affluent have increased what they spend on education by 300 percent while such expenditures for “every other group is basically flat.”

Those with the cultural, financial, and political capital to define worthiness also create and implement policies that say to some, as Brooks notes, “You are not welcome here.” In terms of health care, your body is of no value.

But it’s far more nefarious because the policies are geared to take away from the unworthy the means to consider membership anywhere. They become displaced.

Surprisingly, Brooks confesses his own blindness. He says he recently took a friend to a gourmet sandwich shop who had “only” a high school education.

When she looked at the sandwich menu with “Padrino” and “Pomodoro” and ingredients such as soppressata, capicola, and striata baguette listed, she froze. The tribal “cultural signifiers” got to her.

When asked if she would like to go elsewhere “she anxiously nodded yes,” Brooks says, “and we ate Mexican. (He should have known better; he should have inquired of her from the beginning where she preferred to eat.)

In terms of the health-care policies that are currently being asked for, it is possible that close to 22 million people will never see a Padrino M.D., they will never be the recipients of Pomodoro surgery. The medical counterparts of soppressata, capicola, and striata baguettes will never be there for their ailing bodies to taste.

The only way to end the war is to transcend political economies that speak in terms of deserving and entitlement and to adopt a view of life where we meet the needs of everyone. This means treating the poorest among us as the richest treat themselves. That is a 21st-Century Sermon on the Mount.

Healthcare-wise it means that every citizen of the United States, at the very least, will receive the same level of care a U. S. Senator gets from the collective and the president from private coffers. When this occurs we will finally be able to say: Blessed are the Peacemakers.

It’s always enlightening to see two great minds come to loggerheads over the values they embrace and in doing so shed light on what it means to be human.

What comes to mind first is William F. Buckley’s interview with the great American poet Allen Ginsberg on “Firing Line” in September 1968 — two great thinkers agonizing over what they see at the heart of the American soul. It was Buckley’s show but Ginsberg made it a free-for-all.

Another case comes to mind but it’s strange because the two “contestants” live two centuries apart. I’m thinking of the Roman writer Lucius Annaeus Seneca (c. 4 B.C. to A.D. 65), known as Seneca the Younger, and the Argentinian priest, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, whom most folks better know as the 266th Pope of the Roman Catholic Church, Francis.

Their issue has to do with moral standards as well but more specifically with what is required of a moral person toward those in need, toward the least among us. For Christians the answer’s already there: Matthew 25 says what it is and Mark 10 says how to do it.

Seneca, if your ancient history is fuzzy, was the Stoic philosopher who became the Emperor Nero’s tutor (amicus principis). He had been working with the youth for several years before Nero took charge of the Empire at age 16.

Seneca also wrote Nero’s speeches when the boss had to explain something to the Senate or praetorian guard. In 55, he wrote the much-heralded De Clementia, a treatise on the concept and practice of clemency.

It’s not by chance that clemency came to the fore because Nero had just hired a Roman woman, who was an expert in killing by poison, to toast his several-years-younger adoptive brother, Britannicus — during the family dinner!

By taking on clemency, Seneca wanted to let the Roman Senate and people know that the new emperor was not going to be a neutralizer in the way Caligula and Claudius were; the new man was going to be a man of clemency.

And showing clemency was not a sign of weakness, as Seneca pointed out, but of mensch-hood; it was also a wise political strategy. When someone harmed another, for example, the emperor could demonstrate his power by showing restraint to those in need.

But while Nero’s ventriloquist claims that clemency is good, he makes it quite clear that mercy (misericordia) is not and forgiveness (venia), worse. He said that the person who practices mercy is sick in the head, a pusillanimous soul. A show of mercy is two old ladies being suckered into letting a pleading prisoner go free.

What’s troubling is that Seneca, as a Stoic, also embraced the concept of simplicity. Living like a poor person, he said, was an essential ingredient to living a healthy life (vita beata). And the good person (sapiens) practices what he preaches (“concordet sermo cum vita”).

But in daily life Seneca was a money-grubber; he owned a ton of houses; his personal treasury topped 300,000,000 sesterces. He was a money-lender, a loan shark — though the data on this are slim — whose practices caused great pain and suffering among the Britons.

The Roman writer Cassius Dio in Book 62 of his history says, “Seneca, in the hope of receiving a good rate of interest, had lent to the islanders 40,000,000 sesterces that they did not want, and had afterwards called in this loan all at once and had resorted to severe measures in exacting it.”

Dio says it was the reason the Britons revolted against Rome under the aegis of the famed Queen Boudica, an ancient Jeanne d’Arc.

But we cannot fault Seneca for inconsistency; he was walking the walk, that is, he said mercy was for the dogs and so he treated people like dogs — or is that being too harsh?

The ideas of Nero’s tutor are relevant today because last year Pope Francis had declared 2016 the year of “Mercy” for Roman Catholics. He said every Catholic was called to think about the meaning of mercy in his daily life and then find situations to practice it.

At the beginning of the Jubilee year, as it was called, he wrote “Misericordiae Vultus,” a short note in which he laid out the integral relationship between mercy and Christian identity.

He finished the year with “Misericordia et misera” essentially asking folks how they did thinking about things and whether they planned to make mercy an integral part of their lives.

No one who’s ever read anything about Pope Francis or seen him on TV needs to ask if this guy’s the real deal, whether his “sermo” is consistent with his “vita.” The guy is a font of mercy.

On Holy Thursday 2014, for example, he went to the “Don Gnocchi Center” in Rome and washed and kissed the feet of elderly and disabled women some of whose dogs were bent and swollen. Someone I taught years ago recently remarked that such acts are only symbolic, but look at the photos, watch the videos, this man is in love. When’s the last time you washed and kissed an old lady’s fat feet in a hospital like they were yours?

The Pope lives in a small apartment; he eats with a little community; he drives a little Fiat 500L, which people laughed at when they saw it tootling down Central Park West a couple of years ago.

I’d like to add that for his 80th birthday celebration Francis invited not bishops and cardinals but eight homeless people to his house for breakfast. Once again he was saying that living simply is a component of mercy, which requires that the daily basic needs of the poor and those without be given priority, not stealing health care from the poor to fund tax-cut-handouts to billionaires.

During Bill Maher’s television program “Real Time” two weeks ago, Ohio Governor John Kasich — who lost to Donald Trump in the last presidential campaign — addressed the topic of mercy in terms of health care in the United States.

Maher asked him: Is healthcare a right or a commodity, is it clemency or is it mercy?

Feeling pressed, the governor gave in; he said it was a right. He said his ethical stance on human relationships does not allow him to embrace “the easiest thing,” that is, “[to] run over the weak and those who live in the shadows and those who don’t have much.” He added: “It is not right.”

All this is going on while the United States is engaged in a civil war, is at loggerheads over, its identity. What is America going to be? What “virtues” are in and which are out? Will we include mercy in our newly-constructed national identity?

A lot of people today talk about the importance of “difference” but they confuse it with the million-and-one varieties of cereal on the supermarket shelves; they refuse to take into account the real needs of others that differ from their own. Difference becomes a joke. Then they stigmatize the weak and needy, calling them cheats, deadbeats, freeloaders, druggies, the incorrigible scum of the earth. Why would anyone want to care for that crowd’s health!

Thus these days I hear more discouraging than encouraging words particularly from politicians who spit on mercy; they are assassins of hope.

I love the National Anthem of the West, “Home on the Range.” It says a good place is “where seldom is heard a discouraging word and the skies are not cloudy all day.” I think the writer of that song was talking about mercy, taking into account the needs of all rather than loading them onto a slow train to nowhere.

April is National Poetry Month. For some rhymed souls it is a time to dig out their Mary Oliver and scan a line or two while others sit quietly in their dens hoping the Muse will come and fill their pen with delight.

While such activities are most appropriate during the month when “Lilacs [are breeding] out of the dead land,” as T. S. Eliot says, that is not the purpose of its observance. It’s more complex.

National Poetry Month was established by the Academy of American Poets in 1996 to goad each person in its country to accept responsibility for engaging poetry at an intimate level and to recognize that poetic consciousness is key to spiritual growth and development.

In a way, the month must be seen as one of the 30-day retreats the Jesuits run when people gather unto themselves to assess to what extent they’ve dedicated their lives to the proposition that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”

Those words appear in the second to last line of John Keats’s classic “Ode to a Grecian Urn” written in 1819. And the last line of the poem says, and I’ll paraphrase it here, that that axiom is all a person needs to know in life: beauty is truth and truth beauty.

It is quite a bold assertion and one wonders whether, for example, the mandates of the New Testament might fit into that. But that’s a no-brainer because the New Testament in its own metaphorical terms says the same thing.

The great T. S. Eliot found the Keatsian proposition troubling. In an essay on Dante he veered from his subject for a minute to note, “The statement of Keats seems to me meaningless.” Truth is Beauty and Beauty Truth “is grammatically meaningless” he said. But for a guy who considered himself smart, it’s surprising that Thomas Stearns took such a reactionary road.

He’s not alone. If you go to the Internet and ask for an analysis of the second-last line of “Ode to a Grecian Urn,” you’ll find a lot of other people similarly irked.

Of course we can turn to Buddhism for an explanation — and a case can easily be made — but I’ll offer Carl Rogers, that great-20th-Century-full-of-insight-beyond-innovative psychotherapist who hit the nail on the head in his 1957 essay “To Be That Self Which One Truly Is.” The title is found in Søren Kierkegaard’s “Fear and Trembling.”

In that essay and elsewhere, Rogers describes what takes place when a person goes through the therapeutic process. He says, first of all, that, when a person comes to him suffering from unknown reasons, their inner conflicts have progressed to the point of disablement. The sufferers find themselves being eaten from within.

He says that in their own terms the sufferers reveal that they had tried every possible mode of denial and deceit to smother the truth but all failed and now they were at a dead end.

Rogers goes on to say that, when his patients come into the office, sitting right beside (or more correctly in front of) them is a façade, a wall they’d built to hide their true state of being, from others as well as themselves. But they unable to lay their weapons down.

He said he noticed that such folks also tend to view the world in black and white. Reality is this or it’s that. Transgendered people, for example, have no standing in that denier’s universe. It is far too complex a matter to juggle behind the façade.

But Rogers says that, once the patient feels at home, he begins to dig through the lies that lay beneath his pain. And in doing so he begins to experience a whole range of feelings and thoughts he never knew he had.

Understandably during their sessions the patient weeps, rages, even falls into a stupor of silence because what he said out loud took their breath away. The truth at first is dumbfounding.

But once the patient confronts fear (the word “ugly” can be traced to fear) and acknowledges the truths revealed, he incorporates the new dimensions to make himself whole.

The patient experiences great relief, and often joy, because he is no longer living a lie. As truths about the self are discovered he begins to dismantle the façade a brick at a time.

Rogers also saw, and his patients soon see it too, that hiding behind untruth requires the expense of great energy. Masquerading costs. Plus the patients admit that while undercover they viewed themselves as despicable and ugly because they were treasonous. They had equated not beauty but mask with truth.

Read Rogers’ essays, he alludes to the disdain people feel for themselves when they constrict themselves to living behind a pharisaical wall. His 1961 classic, “On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy,” is a great place to start.

But what’s heartening about the process of unveiling, of opening one’s heart to the truth of is, to the thing in and of itself, is that a person begins to see a radiant beauty in himself. “Then the body of the Enlightened One,” as Anagarika Govinda reports in his “Foundations of Tibetan Buddhism,” “becomes luminous in appearance, convincing and inspiring by its mere presence.” Truth is Beauty.

Indeed, looking upon, experiencing, the wondrous creation of the radiant self, the peregrinator laughs with gratitude because he cannot figure out why he ever agreed to live a life of abstraction.

He sees that experiencing a thing — one’s person — in and of itself, without modification for political economic or other self-enhancing reasons, is beauty.

And when the person begins to recite this experience to the world he dons the mantle of the poet. In spiritual terms the person enlightened begins upon the path of sainthood, the realm of overflowing silence.

Keats was no idiot. He knew what he was saying. That is why we are grateful for Poetry Month, to remind ourselves that we need to put our house in order, the house of Truth, the house of Beauty. No more needs to be said.

Location:

My maternal grandfather owned and operated a wholesale produce business in New York City for over 40 years. When I worked with him full-time during the summer of 1954, I noticed he had a practice of “topping off” his bushel baskets of tomatoes.

When I first saw him putting the greener and less-comely-looking specimens on the bottom of the basket and their rosy-red counterparts on top, I asked why he was projecting a reality that wasn’t there.

An early-on ethical kid, I recall being bothered by the practice and chided him for cheating the truth. He said the practice was de rigueur, introducing me to the concept of caveat emptor, letting persons adversely affected straighten out the truth for themselves.

I loved my grandfather but I started to have a few doubts about him. I thought his M.O. was a form of injustice because, for his benefit, he was depriving others of reality.

Early this year, I was reminded of my “crisis” with Pop when I saw the current president of the United States, Donald Trump, creating and projecting realities that did not (and do not) exist by denying physical reality. Trump incessantly “topped off” facts for his own benefit and sadistically laughed as people scrambled to straighten them out.

On inauguration day, he said there was no rain but it rained. He said he had the biggest crowd in history but photos showed he did not (by far). He said the photos lied.

He claimed three- to five-million people cheated in the presidential election though every Secretary of State of every state said the electoral procedures are so tight no such thing could ever happen.

He also asserted that he was on the cover of Time more times than anyone else — he was on 14 times, Richard Nixon 55 — leaving such distortions for the “emptor” to straighten out. The current (March 23) cover of that magazine reads “Is Truth Dead?” with a lead story “Can President Trump Handle the Truth?”

Last month, Trump hit the jackpot when he accused his predecessor, Barack Obama, of committing a felony by having the FBI wiretap his heavily-guarded golden tower in New York. Public officials from A to Z verified that such an act was a political and strategic impossibility. Houdini couldn’t have done it.

Mr. Trump’s supporters continue to be unbothered by his inversion of reality. Indeed, during the 2016 presidential campaign, he huffed, “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose any voters.”

This is a world radically different from political spin and therefore is accompanied by a whole new range of justifications people use to ease the guilt of their complicity in upending the principles (and laws) of Physics, Epistemology, and Thought.

I am not one to convince (or shame) anyone that they are engaged in mirage-building, mirage-supporting, and mirage-selling. But I notice worry in the eyes of some folks who know they are fooling with the psychological grounding that once provided emotional stability for them.

Thus, what’s at stake today far exceeds Donald Trump’s bushel of lies. It has to do with his followers, and others, radically wrenching their minds to accept the existence of objects that are not there. It’s ideology striving to bring the laws of Physics to its knees.

Thousands and thousands of years ago, the human race decided to reach common ground on what constituted reality by agreeing, for example, that a 1 always equals a 1. It was a way of preventing constant conflicts about whether “this” was “that” or wasn’t. Thus all agreed that a 1 is a 1, and not a 2, and certainly not 3/4. Some say the origin of numbers is unknown but counting was developed to insure justice, to prevent shysters from scamming others through bent truth.

Weights and measures do that as well. We agree on the weight of a “pound” so that some sharpie cannot pass off three-quarters of a pound as a pound for profit’s sake. A pound remains a pound even when it does not appear to be. A pound of feathers is equal to a pound of steel regardless of looks.

And, if someone is buying a yard of electrical wire at the hardware store and the clerk gives him 31 inches, the customer says: You shorted me five inches; what’s going on? The Trumpian hardware man’s retort is: Hey, what I’m giving you is a yard, believe me: 31 inches is 36 inches.

Because of our fears and insecurities and wanting to get a leg up on the other guy, we all have a tendency to shave the truth at times. Often enough we add a little to a 1 and claim 1 1/8 to be a 1; sometimes we shave a little off and claim 7/8 to be a 1.

But Physics condemns the hyperbolic discoloring of reality as hallucinatory. When it’s raining, it cannot be not-raining; a smaller crowd cannot be a larger crowd. It contradicts the Law of Identity as Schopenhauer confirmed: Nothing can simultaneously be and not be.

The wrenching I mentioned earlier has to do with our souls commanding our tongues to speak what the eyes are not seeing. But I am not surprised that such a confrontation between ideology and the laws of Physics and Thought is growing today because it is a symptom of a larger phenomenon.

The great German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883-1969) spoke of “axial ages,” those periods when the old gods have left the stage but the new gods have not yet appeared.

It’s a “liminal” period that Jaspers described as “an interregnum between two ages of great empire.” How insightful Rod Serling was in his ’60s television series “The Twilight Zone.” He said his stories reflected a “middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition.”

The late great Honduran philosophical essayist and fabulist, Augusto Monterroso (has a wonderful fable called “El Chamaleón que finalmente no sabía de qué color ponerse” (The chameleon who finally didn’t know what color to become”).

The story says that the fox taught all the people of the forest that they could counteract the chameleon’s changing definitions of reality by carrying a purse of different-colored glass lenses on their persons. When the chameleon faked a new color, they simply put the appropriate crystal before their eyes and saw his original purple or blue.

The system became daunting, Monterroso says, when the chameleon projected more complex realities of gray or blue green. Now everybody had to use three, four, and even five crystals to see things straight. But when the chameleon realized that everybody had caught onto his system, he decided to adopt it himself.

“Then it became a situation,” Monterroso says, “of seeing everybody on the street taking out and switching crystals when somebody changed colors according to the political climate or to the prevailing political opinions of that day of the week, or even of the hour of day and night.”

In other areas of our lives, political ideology long ago challenged the laws of Physics and Thought but Physics just moseys on with the truth as the Atlantic Ocean oozes up onto the streets of Miami Beach, creating an American Venice in people’s living rooms.

Location:

The democratic republic of the United States that has existed for nearly two-and-a-half centuries is on hiatus. It was on hiatus during the first Civil War and it is back on hiatus now that we’re in the midst of a second civil war.

The Pulitzer Prize recipient and Princeton Historian James McPherson said the first Civil War “started because of uncompromising differences between the free and slave states over the power of the national government to prohibit slavery in territories that has not yet become states.”

The current civil war also started because of uncompromising differences but now it’s between the one-percenters (and their surrogates) and the rest of us over the power of the collective, the “we the people,” to provide for the needs of all as the planet and its sentient beings struggle to rise above conditions of enforced scarcity.

The new conflict has brought to the fore questions which the philosopher movie-maker Woody Allen raised in his two great tragi-comedies, “Crimes and Misdemeanors” and “Broadway Danny Rose”: Is there a moral structure to the universe? Is there some accountability for people who make evil choices and commit evil deeds?

In “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” an ophthalmologist, Dr. Judah Rosenthal, is consumed with guilt because he put a contract out on his flight-attendant paramour who threatened to tell his safe-from-the-ways-of-the-world wife that a pillar of the community had been cheating on her.

After the murder, the doctor goes close to having a mental breakdown. He visits his childhood home to see if he might get in touch with the values he grew up with and they might become a source of stability. In the old house — which the new owner has allowed him to walk through at his leisure — he hallucinates that all his relatives are sitting around the dining room table at a Seder.

He projects a question into their midst about the nature of culpability, and in response nearly every adult at the table offers an opposing view on justice. One of his aunts laughs at the idea that someone who has committed an evil deed will be brought to justice; she says people get away with murder.

That is the view of many people about how the one-percenters manage the world to suit their profit indices rather than to devise and implement strategies to meet the needs of all, health care and otherwise. Thus, for millions, that minority is the source of pain and suffering. And one wonders, if significant dissent arises in contradiction, will they be made to go away like the stewardess?

Standing in the way of any resolution to adopt a position on justice that takes into account the needs of all are the uncompromising differences alluded to. Soldiers on each side of the battle line cannot even agree on the physics of reality, on what sits before the eyes, that a can of beans is a can of beans, so they continue to lambaste each other with condemnatory stigmatizing rhetoric about their respective blindnesses.

Some people I talk to about these things are so engrossed in a knee-jerk meta-reality with no basis in the material world, that they’ve insulated themselves not only from the pain and suffering of others but also from their own need for an existence without cynicism.

In Allen’s “Broadway Danny Rose,” a theatrical agent, Danny Rose, manages a cadre of acts who others define as “losers” among whom are a one-leggèd tap dancer and a stuttering ventriloquist.

Rose is a personalist. He gives himself over to his clients without reserve; he is devoted to them in every way. When he resurrects the career of a has-been singer who winds up with a big hit song, that winner calls Danny Rose a “loser” and ditches him for a high-power publicity agent.

The singer’s girlfriend, Tina, sees the basic goodness in Rose and feels there might be something in him worth pursuing. But she ultimately calls him a loser and ditches him too. His personalism goes unrewarded.

But Rose is able to transcend because he is armed with ethical maxims he learned in childhood. Like a mantra he repeats what his uncle Sidney told him for getting along in life: “acceptance, forgiveness, love.” When things go awry, you accept the other, you forgive the other, you begin to love the other. However, for devoting himself to the lives of others unconditionally, Rose is called by the one-percent a fool.

Today in the United States, where religious views of acceptance and forgiveness have been jettisoned like infernal debris, people talk past each other as if an-other did not exist. Therefore a new measure of justice has to be created that will mollify the factions.

It resides in the question: To what extent and in what way have you relieved the pain and suffering of someone today? Did you meet people at the level of their wounds and bandages and make things better for them? Did you challenge the political economic institutions that keep people locked in poverty and distress though an ethic of enforced scarcity?

Last week, I mentioned to an older woman at the Y that Pope Francis had celebrated his 80th birthday by asking eight homeless people to breakfast. I related that he chatted with each person individually while sharing Argentinian cakes with them before saying Mass. Besotted in cynicism, the woman implied the Pope did this as a publicity stunt.

I asked her if she thought the Pope was stunting last Holy Thursday when he met with men and women prisoners at Rome’s Rebibbia prison and washed their feet like Jesus had done on the Thursday before his death.

I asked her if she had ever visited someone in prison who had no family or who had been totally rejected by society. Did she believe in acceptance-forgiveness-love? I must admit there was a great pause of silence.

In “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” the killer ophthalmologist finally pushes through his homicidal guilt, he is never caught, he goes on living his one-percent life with his one-percent wife. His aunt was correct, people do get away with murder.

There is an intermittent voiceover throughout the film; a philosopher, Doctor Levy, offers a vision of a way out of internecine conflict. He says, “We define ourselves by the choices we have made. Human happiness does not seem to have been included in the design of creation at all, it’s only we, with our capacity to love, that give meaning to the universe.”

It is actually an optimist, democratic, republican solution to conflict in that it invites all to participate in creating human happiness. But sadly, things got too tough for Doctor Levy and he took his life amid the insensitivity.

But in a epilogic postscript to the film, Levy reminds folks that “most human beings seem to have the ability to keep trying, and even to find joy from simple things like their family, their work, and from the hope that future generations might understand more.”

But will future generations understand anything unless the collective “we the people” becomes personalists, like Danny Rose, and dedicate ourselves to meeting the needs of the planet and all its sentient beings?

And when the woman, who called Rose a loser and derided him, fell on hard times and knocked on his door one Thanksgiving afternoon while the loser was feeding all his loser acts in his apartment (with TV dinners), all he could hear was Uncle Sidney: acceptance, forgiveness, and love.

He failed at first, he could not say the words, she left forlorn. But after a moment’s deliberation he ran after her. And there on Seventh Avenue in front of the Carnegie Deli, on Thanksgiving Day, was the incarnation of love.

Location:

I’ve been wanting to say something about the meaning of Christmas for some time now. I’ve gone through so many transformations about it and I know others have too but they say nothing about it unless asked. They’re kind of embarrassed because they know they’ve “sold out.”

I know that for a fact because, when I’ve engaged certain people about what Christmas means, a goodly number submissively admit they succumbed, that is, sold out to the marketplace.

But anyone who makes a judgment that someone has sold out Christmas has to come up with some kind of definition of what Christmas means and what selling out means and — it might sound tautological but I’ll add it anyway — what a true Christmas is. It’s a shame but today that emphasis “true” has to be added to everything.

In this age of ersatz democratic participation — where every kid who runs a race on Memorial Day gets a ribbon that says he or she’s a winner — it would seem that one definition of Christmas is as good as any other but that is not the case, I repeat “not.”

Let me start out with the manger scene: Mary and Joseph are looking for a place for Mary to have her baby. They can find no Holiday Inn with a vacancy so the child is born in a stable and placed in a manger kept warm by a wrap of swaddling clothes.

This is not the exact chronology of the nativity story but some shepherds show up for the birth and angels arrive and sing songs that are played on the radio to this very day.

Earlier in the story, the gospel writer says an angel appeared to the mother-to-be and told her: Lady, you will give birth to a revolutionary, don’t worry, it’ll be OK, it’ll be a new way of doing business and it’ll outlive him two-thousand fold.

But the angel was not telling the whole truth about revolution. She did not reveal that, if you refuse to sell out, you will find great joy in life, in fact will find life eternal but you have to give your life for it. A very complex promise and a very big leap of faith.

So what does selling out mean? It means, first and foremost, you will never create “fake news,” you will never base any life decision on what you do not know to be true and never say anything that is not true. Later in life, the aforementioned revolutionary,when put under the gun by questioning authorities, quipped back: You guys have no idea what Truth is. The actual wording is: quid est veritas?

To get to the truth means you have to get to words before the marketplace does, before the nation-state does, before institutionalized religion does, which means a person has to go to where words are born, to the very font out of which words flow and come into being. You have to become a midwife of words and thereby breathe in the untainted word as it comes out of the womb of silence.

Christmas then is a story about the well of silence where the words are born and about believers camping by that well so they can hear silence speak truth to power.

This is a tall undertaking because it means a person must commit to silence, which requires a certain stripping down of the elements of “noise,” a big part of which in the United States these days is lying about reality, about what sits right before the eyes.

It’s the old Social Psychology experiment come true: A group in on a secret “forces” a person to deny what the person sees before his eyes. The stooge sees a 7 and calls it a 5 because that is what the others said.

The poet in us, among us, does not succumb to this kind of spiel because poets sit by the well of silence and wait for words to be born. It’s what they do for a living; they refuse to succumb. It’s a daunting way of life and one that requires great discipline. It’s not Donald Trump spewing realities that do not exist, that never did, and never will.

But most people think poets are useless, that they waste their time fiddling around with words when, in fact, the opposite is true. They are bringing the revolutionary message of Christmas unprejudiced by, unhindered by, any sectarian creed. For poets, a 7 will always be a 7 — no more, no less. They would never confabulate that Hillary Clinton was involved in a sex-ring trade. Every word the poet writes contains the forceful truth of the Law of Gravity because it is a word born directly from the womb of silence.

Thus the true Christian message is: If you wish to be free, if you wish to share in the revolution Jesus spent his life talking about (and living), you must embrace a life of poetic consciousness that entails taking the life of silence seriously, listening to each word as it’s being born: daily, hourly, by the moment. It’s a radical shift in consciousness.

It’s life lived in a manger — and why so many poets died destitute — where nothing counts but the word being born, of its own accord, untainted by marketplace, State, and institutionalized religion.

The fire of that message is so great that the person on fire is compelled to sacrifice his or her life for it, like Jesus did, through a life of unparalleled service. Destitution and death are mere annoyances.

The Catholic Worker revolutionary, Dorothy Day — whom some have put up for sainthood in the Roman Catholic Church — knew about that sacrifice. She wrote a book called “The Long Loneliness” in which she speaks about the price a person has to pay listening to and recording what silence has to say.

I sometimes imagine a big Christmas store where there is nothing but a small well of silence in the center where believers come to gather, and sit, and quietly listen.

Some listen for years and do not hear anything but their commitment to silence does not wane. Even in despair I’ve heard them sing the words to Merry Christmas, the first verse of which says no one will be happy until the needs of every human being are met.

The second verse speaks about “the 1 percent,” keeping their foot directly on the throat of humankind so that meeting the needs of all is mocked from behind a golden plate of caviar.

Oh, when I first got into this stuff, I never realized how much the Christmas revolution had to do with making people happy, as in each and every person having the same income, regardless of anything, and receiving the same care for body and mind as the richest among us — from the day they’re born to the day they die.

Boy, that’s my kind of Christmas. But I cannot say anything more, I’m sitting by the well of silence here, waiting for my next mission impossible.