For Anthony Cronin

Though I’ve never seen it written in a history book, May 27, 2017 is a day that lives in infamy.

A flotilla of ships was not bombed in a faraway port or the tops of towers cut with the wings of enemy planes. It was the day that Smith’s Tavern in Voorheesville, New York closed its doors forever. A pall came over the town.

Hospitality had been the signature dish served in that building for 117 consecutive years in the form of food, drink, and a place to stay upstairs — sometimes the owner lived there.

During that time, the property changed hands five times. The Smith in Smith’s Tavern came when the Frank Smith family took over the business in 1945. There was a Frank Sr. and a Frank Jr., the son still held in honor today.

When Smitty’s — that’s what the place came to be called — finally shut its doors, I thought it was part of the jinx.

That is, Nick Oliver — who raised the building in 1900 as the West End Hotel — saw his 15-year old daughter die within a year.

And shortly after Ernie Albright bought the place, his baby girl, Coretta May, died. A 1915 edition of The Enterprise said she was “aged 2 years 9 months, 8 days.” And that her “funeral was held Wednesday morning from the West End Hotel, where her parents reside.”

Albright felt the jinx — he changed the name to the Brook View Hotel.

The editor of the paper who reported on the child’s death felt compelled to offer the community a maxim of consolation: “There is no flock however watched and tended, but one dead lamb is there; There is no fireside, howe’er defended, but hath its vacant chair.”

Some of Smitty’s patrons I met over the years would fully understand the meaning of that because they themselves were outside time, like characters in a storybook. I see their faces clear as day as I write this.

The tavern was situated on State Highway 85A diagonally across from the village elementary school and a few hundred feet from the Vly, a beautiful creek that winds through Albany County.

But go there today and all you’ll see is a frame looking like a soufflé ready to fall or a Halloween pumpkin slumped in winter snow.

For 50 years, when Friday night rolled around, friends, neighbors, and especially people with kids, headed to Smitty’s for a night out.

Sometimes there’d be a wait but nobody cared, it was a time to say hello to a neighbor at the bar or a family seated at a table waiting for dinner. The buzz of the place was a beautiful piece of music.

And, while it can be said there was no such thing as a stranger at Smitty’s, at times one of the regulars got out of hand and had to be talked to. I never saw a fight at the place nor even heard a voice raised in anger — though at times the owners did call for public assistance.

During the tenure of the last owners — business partners Jon and John — the place sported a poets’ corner, which the regulars at the bar knew well. Nailed to the wall by the heated soup tureen was a street sign with block letters that read POETS’ CORNER. It’s in the village archives now.

There are two other great institutions that have a poets’ corner: the famed Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine in New York; and Westminster Abbey in London (where Mr. Chaucer resides).

Nearly always, as you came through the front door at Smitty’s, you’d catch a fluffle of poets in the corner, reciting Keats or debating Miss Emilie’s pedigree. Above the street sign was a plastic holder with copies of the poem of the Poet of the Month. Inquisitive regulars always availed themselves.

Jim Reed — who stood at the end of the bar that curved into the kitchen, a short one in front of him always — read the poems with childish delight. One day he got into a terrible fix over the word “rill.”

And when National Poetry Month rolled around in April, some of the poets put on a confab called the Smith’s Tavern Poet Laureate Contest.

The prizes were underwritten by the owners: $100 for Laureate; $75 for second place; $50 for third. Poets came from Massachusetts and as far west as Utica.

On contest day, you could hear the genial buzz as the poets and their fans packed into the dining room shoulder to shoulder: The owners were reimbursed after the first hour as pizza, whiskey, beer, and esoteric stout filled the tables nonstop.

And while the poets read their work amid the deepest silence, the waitresses served drink and food in the tightest of spaces with ne’ery the clink of a plate. At Smitty’s, the waitresses were impresarios; most were older women with day jobs who came at first to make an extra buck or two but soon became part of Smitty’s family.

Some were there for 30 years. I won’t name any here but their sweet womanly kindness I still feel today — better than anything on TV’s “Cheers.”

From time to time one of the waitresses, while waiting for her orders to come, penned a line or two on the back of a placemat and brought it to the poets for their review: brass duende, but always the best of fun.

And with respect to the pizza itself: Each year, when the region’s “best of” notices came out, Smitty’s was right near the top. In a 1989 interview, Frank said he’d just finished baking his millionth pie — but that quality was always the measure.

At the beginning of the week, he’d head to the butcher to buy the best prime beef for his burgers, served beside the incredible German potato salad of his German-born wife Gert, a force in her own right. They used to refer to themselves as equals.

And some nights after the kitchen closed, Frank would make the rounds and hand out little gifts: one time a frisbee with Smith’s Tavern printed on the side; another time a key ring with nail file and pen blade enclosed — Smith’s Tavern engraved on the side. I always marveled at the quality of his offerings.

And just as sandwiches at the Carnegie Deli in New York had names, so did Smitty’s pizzas. A person might walk in one day and say: I’ll have the “John Gray.”

But all that’s gone now and Voorheesville is worse for the wear: a life-giving organ of its collective self sold.

In 1916, Mr. L. J. Hanifan, the State Supervisor of Rural Schools in Charleston in West Virginia, wrote about the disappearance of communal treasures that might be as small as a quilting group — never mind the community bee that brought the stones for Nick Oliver’s foundation in 1900.

In “The Rural Community Center” Hanifan wrote, “When the people of a given community have become acquainted with one another and have formed a habit of coming together upon occasions for entertainment, social intercourse and personal enjoyment, that is, when sufficient social capital has been accumulated, then by skilful leadership this social capital may easily be directed towards the general improvement of the community well-being.”

“Social capital” is not money or real estate but the communal joy people experience living with others in mutual aid and fun and bonding in accord.

Some days I wonder if there’s others who feel the loss as I do. When the place was sold, angry critics said the owners had no right to sell a public trust.

Frank Cramer, who bought the place from Ernie Albright in 1937 and called it the Cramer House, was part of the jinx: He died upstairs, never thinking a place like Smitty’s would suffer a fate like his own.

Share your reading list with me and I will tell you who you are; a reading list is food and we are what we eat.

And, if you tell me you do not have a reading list, I will tell you who you are as well: why you’re starving, and how to restock your shelves to offset the disease.

Years ago, I was editor-in-chief of an international journal on justice called Contemporary Justice Review. It’s out of the U.K., under the imprint of the esteemed Routledge, a subdivision of Taylor and Francis. It was my brainchild.

For a proposed special issue of the journal, I put out a call for papers to the academic community — as well as the public at large — asking folks to submit an essay on their moral and ethical development, that is, the emotio-socio-cultural foundation stones on which their being rested, a personalist vision of what Nietzsche was talking about in “On the Genealogy of Morality.”

Thus the writer had to reveal his overriding vision of life — concepts like freedom and justice — as well as the spiritual foundations on which his rules of life were based, his system of ethics, and because all rules and ethical systems have to do with happiness, the call for papers was essentially asking the writer to say what made him happy.

Delineating such mental frameworks is not an easy task; it requires naming the persons, places, and events that shift the axis of a person’s being and force him to build his ethical foundation anew — from the bottom up.

Thus, if a writer saw himself as a five-story building, he had to say how (and why) each floor came into being, right down to the rooms. It’s a level of self-analysis the great psychoanalyst Karen Horney championed all her life.

The special issue of the journal never came about; the response was too lukewarm — and I knew why.

First, the process is painful. The writer, explorer, thinker, analyst, must engage in a near-Marxian economic analysis of every aspect of his life — every person, place, and event — and reveal the worth he has assigned to each.

The human personality is a pool, a gestalt, of all such rankings combined. And they might be as basic as: I like pasta over pizza but, on a larger social-structural level, it’s: men are superior to women; whites outshine Blacks; fascist societies surpass those where people have a say.

And the ranking process is not some option, it’s grounded in our DNA: parents do it with their kids. They say they love their every child the same but deep down say one of the kids tugs on their heartstrings in a special way — a hierarchy of worth. A Freudian would say it’s the ego moving the soul toward Nirvana.

When a person’s rankings leak out and I’m there, I always ask how they came to be. Economics are not Marxian but arise with the birth of time and consciousness. The human being prices things like the Antiques Roadshow.

When people get old and lose their inhibitions, they say aloud — often to the embarrassment of their kids — what they think a thing is worth. Life’s clock freed them; saying their piece is a source of peace.

As a country, as a culture, America has long rejected reflective self-analysis — what do the Proud Boys read? — thus splinter groups keep springing up that lionize aggression and violence, nihilists who deny the worth of anything not themselves.

On the other hand, contemplatives — I read their work daily — speak (and write) a poetry of peace. It might not be Yeats or John of the Cross but it’s the language of mystics.

The issue of my journal never came about as well because contemplative self-reflective activity is not rewarded in the academic marketplace; it does not lead to tenure or a full professorship. Who will pay for periods of meditative reading and a space for solitude (could be a room in the public library) and, for some, a pen to log their experience?

But people reject such a life because they view solitude as loneliness, with being disconnected from everything that makes them happy: phone, TV, computer, shopping. And they are partially right because solitude requires time alone.

The irony is: The deeper a person’s solitude, the more he’s connected to others — a paradox of consciousness. It translates into living in accord with “other” at every level: neighborhood, town, village, partner, mate, and family; aggression and violence are rejected as means to deal with “difference.”

The aspirant speaks of such accord with elation and strives to keep that way of life intact. Some Asian mystics say they fear no hardship because they can sever soul from body — elation as inexhaustible.

I love to write. I love to read what I write, I read what I write over and over, it’s a source of meditation: a record of me listening to myself in solitude. It’s not trite to say it’s a gift.

The great psychoanalyst Carl Rogers said that, when people came in for therapy, they came packing a facade behind which they were hiding all the assessments of worth they made of every person and being in their life, including themselves — and the repression was killing them.

The aggressive, violent American we see in the papers and online today — even those in public service — is hiding behind a façade that keeps breaking out into violence: sometimes with a gun; sometimes in denial of reality; sometimes with a flag pole — to which the American flag is attached — beating down on a neighbor the community hired to keep itself safe from flag-pole-beaters like themselves. Communitas non compos mentis.

Seven years before Nietzsche’s morals book came out, his overlooked “Daybreak” appeared in which he called for the “reevaluation of all values.”

He said, “I go into solitude so as not to drink out of everybody’s cistern. When I am among the many, I live as the many do, and I do not think as I really think; after a time it always seems as though they want to banish me from myself and rob me of my soul and I grow angry with everybody and fear everybody. I then require the desert, so as to grow good again.”

Where America is now: in the desert trying to find a way to grow good again.

When he was 16, the writer-thinker extraordinaire, Aldous Huxley, was struck with an eye disease that left him blind for 18 months. Years later he recalled, “I had to depend on Braille for my reading and a guide for my walking with one eye just capable of light perception, and the other with enough vision to permit of my detecting the two-hundred foot letter on the Snellen Chart.” That’s the long black and white rectangular chart doctors and government agencies use to measure sightability.

Huxley did regain some sight but had to rely on thick-lensed glasses that wore him down as the day wore on. And this a man whose calling in life was reading and writing books for nearly half a century. (His “The Doors of Perception” is about sight’s relation to mental health.)

In a similar way, the great Irish writer James Joyce had trouble with his eyes. He underwent 12 operations. In his biography of the Dubliner, Gordon Bowker says after those operations Joyce couldn’t, “see lights, suffering continual pain from the operation, weeping oceans of tears, highly nervous, and unable to think straight.”

Like Huxley, he became “dependent on kind people to see him across the road and hail taxis for him. All day, he lay on a couch in a state of complete depression, wanting to work but quite unable to do so.”

In the classic photos of Joyce, the first thing you see are the glasses (maybe the hat) fitted with thick-hazed lenses.

Gradually biographers have come to reveal that Joyce contracted syphilis and that that affected his eyes. In 1931, Joyce said, “I deserve all this on account of my iniquities.”

There are many differences between the two writers but one that stands out is that Huxley wrote a book on sight called “The Art of Seeing.” It came out in 1942, thirty-two years after he was first struck.

To help himself, Huxley adopted a sight-improvement module developed by a certain Doctor William Bates; he adhered to Bates’s regimen and his eyes improved. He became a devotee.

But some doctors raised concerns about Huxley’s claims; one reviewer of the book said Huxley “borders on the ridiculous.”

Pasted on the inside cover of my 1943 Chatto & Windus cloth edition is a small newspaper clipping with a headline that reads, “A council bans Huxley eye book.”

The text says, “Southport [England] libraries committee have refused to purchase Aldous Huxley’s book, ‘The Art of Seeing,’ in which he describes how his sight was restored, on the ground that it is more likely to do harm than good.” Whammo.

It does not say who the committee members are, whether librarians following doctors’ orders or taking a stand on ophthalmological health in accord with the ethics of their profession: a meaningful difference.

Bates deals with the psychological dimensions of sight and Huxley goes a step further. He says a lot of the “mal-functioning and strain” people suffer comes from their psychological make-up; that is, a person’s emotional gestalt affects what he sees.

Sounding like Freud, Huxley avers, “The conscious ‘I’ interferes with instinctively acquired habits of proper use.” That is, constrictive ideologies set up a mental framework that ambushes biology: the cornea, lens, all the parts of the eyeball that allow people to see (straight).

He says people try “too hard to do well … feeling unduly anxious about possible mistakes.” Not at home with themselves, they worry about failing which affects their sight.

The reviewer who criticized Huxley did say the philosopher was “quite right in saying that visual disabilities are often muscular and often psychopathic in origin”; thus people can help themselves by adopting protocols like Bates’ [not an endorsement].

The reviewer concluded “The Art of Seeing” would be good for psychiatrists “as an intimate and revealing self-study in psychology.” Which can be taken two ways: (1) that “The Art of Seeing” is a memoir worthy of attention or (2) that Huxley needs a psychiatrist.

One example Huxley gives of how psychological make-up affects vision is a woman who’s terrified of snakes: Walking along one day, she does a double-take thinking she just saw a snake; she looks again and sees only a piece of rubber tubing.

Huxley said memories of snakes had imprinted themselves on her imagination and were ready to surface when called upon. It’s the psycho-philosophical-biological condition of (1) seeing what is not there or (2) not seeing what is.

A lot of people reject examining these issues because it requires considerable self-analysis, and America hates self-analysis.

It’s such a coincidence that, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980, the Polish poet-writer Czeslaw Milosz took up the matter of sight.

And he gave as an example the stories of the Swedish writer Selma Lagerlöf in her “The Wonderful Adventures of Nils.” (She was the Nobel Laureate for Literature in 1909).

Nils is 14-year old Nils Holgersson who flies high above the earth on the back of a gander and sees the whole of life in context.

He sees “both distant and … concrete” at once, which Milosz calls “double vision,” seeing from up above and up close simultaneously. He says that’s how poets see, and it is the apex of clarity.

The slovenly neurotic sees up close but has no overview, lacks perspective; the abstractionist on the other hand sees from up above but cannot see what’s in front of him.

Giuseppe Tucci in his classic “The Theory and Practice of the Mandala” (1961) says those forms of neurotic blindness cause “spiritual sterility.” But, when a person sees from up-above and up-close simultaneously, like a poet, a “new consciousness” arises. Simultaneity is key.

The up-above stands for wisdom and the up-close the discipline of daily life. Without the union, the simultaneity, Tucci says, there’s never a “return to the summit of consciousness.”

As America struggles to find the words to regenerate Her self, She’s also having a hard time seeing from up above (like Nils Holgersson) — She lacks perspective — and that is why ideological skirmishes keep flaring up.

Way back in 1938, the two great American songwriters, Johnny Mercer and Harry Warren, described the eyes of the double-vision-seer. Their song begins:

Jeepers creepers

Where’d you get those peepers?

Jeepers creepers

Where’d you get those eyes?

Gosh all, git up

How’d they get so lit up?

Gosh all, git up

How’d they get that size?

I started studying Spanish in a university classroom years ago when I needed to converse with people at the Albany County Jail who’d been locked up for coming to the United States without papers.

Early on, I talked to the prisoners with a college student as my translator but, after being stood up twice, I took charge: Español.

I have an advanced degree in Greek and Latin and studied French for years and later Dutch, while writing a book on crime and punishment among the 17th-Century Dutch in Albany (Beverwijck then), and had an interest in language since high school, maybe as an altar boy.

And when I started to study Greek and Latin and French, I took an interest in how language works — its linguistic forms — as well as how people pick words to say what they need to say; there’s also the matter of the range of meanings a word can have without losing its identity — words can stretch only so far.

A problem in the United States today is that a sizable portion of the population turn words upside down at will, using them to mean what they do not, and cannot, mean — causing anxiety in everyone. At one time “that” meant “that” but the schemers say “that” now means “this” or some other text du jour. It’s an upheaval that batters at the walls of sanity. And the greater the battering the greater the loss of consciousness.

French flowing from Greek and Latin is a Roman(ce) language so I was interested in how words went from parent to child — as well as how the child develops a common language. It’s more than Deus becoming Dieu.

And though language constricts the tongue by summing matters up, my long-term interest has been in how language frees. Which always involves the subjunctive — the mood of doubts, possibilities, fears, and wishes — containing the secret of how a society comes to exclude some from a bounty meant for all. As in justice for members-only.

The kids in my first class, 101, were 50 years younger. They all had Spanish in high school — I was surprised to see how well they spoke though sometimes it seemed hollow, as if they were skating on top of the tongue.

And they knew nothing about grammar — society’s agreed-upon rules for saying things economically, being understood with the littlest effort — I cannot recall one of them asking the teacher how a society learns to speak cordially.

For me, the toughest assignment in 101 was the five-minute presentation each student had to make at the end of the semester, in Spanish, in front of the class, no notes. The speaker had to use nouns and verbs in flowing sentences: no rattling off vocabulary.

We were told we could speak on any topic we liked.

At the end of each chapter in our text there was a short selection in Spanish of the work of a famous writer or artist — a poem, an essay, a biographical sketch.

One of the writers featured was the Nicaraguan poet, Rubén Darío, whom the book called the Father of Modernism, El Padre del modernismo.

What stunned me was not that he shaped how poetry was done in “the colonies” but back in Spain as well. He was a revolutionary: a sea flowing back upon itself, the vanquished a conqueror.

I picked Darío for my talk.

Just about every other kid — I hate to say all — picked something like “at the beach” (a la playa) or “drinking cerveza”; a complex topic was “cerveza a la playa.” But maybe somebody did do Frida Kahlo.

On days that presentations were made, I was amazed to see that none of the kids seemed nervous — I think because they had PowerPoint at hand — everyone made a PowerPoint presentation: the playa people showing slide after slide of beautiful white beaches stretched along beautiful blue water — a back-from-vacation travelogue — and the cerveza contingent projecting guys in party gear celebrating cerveza, 20-year-old dorks — excusez moi — skating along the bottom of the tongue.

When the slide was something the kids found funny, a titter ran through the room — they saw themselves. I heard nothing about Spanish-speaking cultures — here, Spain, or anywhere. Maybe someone did do Kahlo?

I grant the age gap between me and my classmates as well as the divide in education and culture — I taught at that university — plus I’m a poet in love with language: but I thought maybe one or two would be interested in someone who changed the way people lived.

To tell the class about Darío, I did not use PowerPoint — I don’t like it — but came with pieces of poster board — 12-by-30 inches or so — on which I’d pasted pictures of Darío and his environs. Following good pedagogy, I panned the photos left to right across the room, slowly, so everybody could see, holding them high for the mezzanine, while giving my spiel en Español.

I did not see eyes sparkle with Darío, nor faces light up over modernist poetry in Spanish, not even interest in someone who had such an impact on life that people called him Father. There was no titter.

Something about the beach/beer presentations bothered me. They dismissed the treasures of the Spanish-speaking-Spanish-writing art and culture world, the lives of those who shape the common tongue.

The kids accepted my posters; I think they were saying, let’s give the old guy a break — which I’m not doing here, calling them on their juvenile beer/beach infomercials.

I made my disappointment known to the Spanish Department, asking if there was a way to get the kids to be serious, to submit to a foreign culture, address the Spanish-speaking world in words beyond beach and beer.

The next semester, when it came to choosing topics for our talk, the teacher handed out a sheet with a list of acceptable themes — poets, writers, architects, people of justice — I wondered if I’d had a say in it.

One thing I liked about my Spanish classes — and language classes in general — is that, when someone makes a mistake, the teacher doesn’t wait till the end of class to correct the error, or write a letter, but corrects the student in the flesh on the spot in front of all — “Willie, it’s not manana it’s mañana” — which I liked — correction and redemption rolled into one.

There’s more to say, in that the poet who moved into Darío’s house, after his family left, was Alfonso Cortés. I presented him to the class the next semester, pasting photos on placards like I did with Darío, and later I wrote a paper on him that I presented to a local poetry group — translating his poems.

There was no need to mention Cortés at the jail but at least the prisoners and I could speak as one. In one case ICE got involved — the local agent was a woman of justice — the deported soul was back in a week.

How sad these days that even the guy next door turns words upside down and seems to relish the doubt and confusion he creates, even in the suspicion and hate that follow — a spike in the human heart.

America is having such a hard time admitting She’s crazy, that She’s split and quartered like a side of beef, begging for therapy. Words fly by with such vehemence and rage that people at Anger Management think they’re in Jurassic Park.

And I went to every class with an open mind.

If we use the final days of the Roman Republic as historical precedent, or cultural backdrop cum mirror, to understand what’s taking place in the United States today — politically and socially — honesty forces us to conclude that the Republic of the United States, as happened to Rome, is done for.

No one wants to be the bearer of bad news but the similarities between the two Republics are overwhelming, especially when it comes to the violence and deceit associated with elections toward their end. And anyone who dismisses the parallel because Rome was way back in B. C., is a fool. Theodor Mommsen’s five-volume “The History of Rome” says why.

In early summer 2021 A. D., turn on the TV any time of day, listen to the radio, read the papers or what’s posted on social media: There is an endless flood of fearful cries foreboding the end of U. S. democracy, the demise of the Republic, while a violence-driven faction — even inside the government — spews trash-talk against the “collective” and creates legislation and propaganda networks that hack away at the social bonds a republic needs to stay alive.

A republic is not just a type of government, it’s a community where people bind themselves through mutual aid, knowing well that such an ethic is the first step toward preserving collective social life.

And the capitalist economy that runs through America’s veins like plasma in the blood, is hastening the demise of the Republic as its richest people propagandize that to be rich you cannot contribute to the collective; paying taxes is a waste of personal funds.

Indeed a few years ago, a former president of the United States, a billionaire, got on television and told the American people that anyone who contributes to the collective by paying taxes is a damn fool. He said it grinning with satisfaction, calling collectivists suckers. He said he beat the system and that’s how he stays rich.

Indeed, through the support of the rich, a tax code exists that ensures that they — and those of their ilk — remain above socio-political upheaval, untouched by the volatile ups-and-downs that invade the lives of the poloi.

Such engineering masks the connection between the “collective” and repaired roads, collected garbage, van drivers taking old and lonely seniors to the doctor, dog-control officers, and new desks for a rural elementary school that just might spark a child to take his studies seriously.

Part of the deep-seated animosity that exists in American society today arose when a significant number of Americans adopted the anthem of the rich but failed to achieve what it promised — and became infected with a virulent hate. On Jan. 6, 2021, that hate became lethal through an armed insurrection. Of course the country’s Capitol building was overrun but what was stormed as well was the bastille of community, of mutual-aid-based relationships, of a Republic that says the well-being of every citizen deserves equal attention.

By storming the Capitol, therefore, the rioters were also hacking at the life of the municipal minimum-wage van driver who takes old folks to the doctor, helps them out of the van, walks them up the steps to the office, insures that they get logged in, helps them settle in the waiting room, and then goes out to the van to wait until the appointment is over.

He then goes back in and collects his charge, asks the receptionist if there’s anything they need to know, walks the 93-year-old Widow Vanderpool back to the van, eases her into a seat, and chats with her on the way home, the only real conversation she had all week.

Understandably a happy van driver makes all the difference in how a mother is treated when her son can’t get off work to drive her himself. And the people carted in the van might not be old but have mental problems, a leg in a cast, or no one else in life to take them.

The community van-driver — metaphorically and actually — earns “nothing” because he is an expression of the collective, of community life where citizens provide for each other, as in taking the Widow Vanderpool to the doctor because she had no one else to call upon.

I’ve found nothing so far that says Bezos, Buffet, Trump, and others on their rung funnel funds to towns and villages to provide rides and services for people in need. And, as the Republic disintegrates, the number of people falling through the cracks of needs-unmet keeps growing.

A woke person might say disregard for the collective is a form of violence (at a distance), which an economist can make a case for with numbers. And those who war against collectivity are successful because they propagandize with an ideology of scarcity, a gospel of fear, that says there’s not enough to go around — and a horde of dirty Mexicans is hurtling toward the trough. Eat that dog before he eats you.

Because of such thinking and the hate it rewards, the United States is dying not from a heart attack — as was the case in B. C. Rome — but from congestive heart failure; the Tin Man of Oz, who finally found a heart, is watching it die before him.

When I hear the jeremiads on cable news saying the Republic is done for, I hear the voice of Cato the Younger — the Stoic philosopher who became a Roman senator to resist monarchy — and that of Rome’s most famous barrister, Marcus Tullius Cicero, both decrying the power-based hustle and violence that autocrats like Caesar championed. That nation inflicted death upon itself that a modern-day coroner would call suicide.

Look at the texts; in the early Fifties (B. C.) candidates running for office in Rome campaigned with gangs by their side, commanded paramilitary units who engaged the opposition on the street.

Things got so wild in 52 that no consul was elected. In the United States, that’s like saying social upheaval was so severe no president was elected.

The Roman senate called in Pompey the Great — the adulescentulus carnifex, the boy butcher — who got the name because he knew how to handle problems. The senate made him sole consul and provided him with an army to keep things under control.

The Greek-born historian Plutarch says, during elections, candidates presented themselves “not with votes, but with bows and arrows, swords, and slings.” He said they in fact, “would defile the rostra with blood and corpses before they separated, leaving the city to anarchy like a ship drifting about without a steersman.”

After a while, Plutarch says, “such madness and so great a tempest” wore people down so they were ready for a dictator to calm things. Being a political automaton — forget republican citizen — was better than being a billiard ball careening against the cushions of fractured social life.

Is that the ethical choice facing Americans today: political automaton or billiard ball? Years ago Robert Putnam, in his classic “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community,” said America’s greatest fear was folks living in isolation; today that isolation has morphed into confused and hate-driven souls spraying the collective with AK-47’s — 247 times in 2021, and the year is hardly half done.

Psychologically-speaking, when the human creature — a person — has a hard time dealing with some ugliness in himself — and does not have the strength to deal with it directly, that is, absorb it into consciousness — he spits it out. Psychologically-speaking, he projects.

The process is not unfamiliar; people accuse each other of doing it all the time — if not face-to-face, they’re thinking it. A cheating husband starts calling his wife unfaithful; a pathologically-lying politician calls people who challenge him, liars. It’s what sociologists refer to as “labeling theory.”

Projection is a handy psychological tool because the actor casts his “problem” elsewhere: It’s now outside, in the external world; the projectee is bearer of the ill.

These days, we think of “projection” in terms of people, one person projecting onto another, but, in many traditional anthropological cultures, people projected their ills onto things like sticks and stones. A man who had a fever would rap a stick, toss the stick away, and the fever would be gone. The traditional biblical image of “scapegoat” is the tip of the iceberg.

The maddening paradox about projection is that, regardless of the ailment a person projects, no real transfer — psychologically-speaking — takes place. The problem, the ill, still resides within the projector; the pathological liar is still a liar; the cheater, still cheating.

Projection is hydra-headed in that it includes the ill the projector is trying to get rid of; the act of projection; the reception of the weight by the other; the ill-will created; and the low-level depression it causes.

To force potential projectees to submit, as well as punish those who refuse to accept the lie, the projector develops a vocabulary of “bully-talk.” It reflects a radical shift in the person’s cognition-network and explains why it’s near impossible to get projectors to confess; they refuse to give account.

Projection is economic in the sense that it involves the redistribution of worth; the projector enhances his own worth by getting rid of negativity and the dumped-upon is diminished by the burden imposed.

In his famed “Golden Bough,” the brilliant social anthropologist J. G. Frazer provides endless examples of tribes in all parts of the world getting rid of physical and psychological ills through custom protocols such as rapping a stick or bathing in a river.

In ancient Rome, Frazer says, a sick person cut his nails, rolled the clippings in a ball of wax, then stuck the wax to a neighbor’s door (in the dark of night) — whoever opened the door first got the fever.

Thus projection is a form of the Pontius Pilate Syndrome because the projector refuses to accept the negatives life has assigned him or that he brought upon himself — as when he chose to become a liar for the sake of power. Abdication is a powerful drug.

In the United States today, the projection process has become so rampant that people see evil everywhere. Social resentment is white hot.

The most glaring example is the Jan. 6 extravaganza when a mob of disaffected arch-projectors raided the United States Capitol and beat with a pole — attached to the flag of the country they live in — those the country had hired to protect “them” from people like themselves.

What is most alarming is that the mob of arch-projectors had redefined projection to mean eradication. A simple transfer was no longer effective, the other had to be eliminated; a goodly number of the assailants wore shirts celebrating the Nazi extermination of six million Jews: fascists!

But there is another process — psychologically-speaking — that goes in the opposite direction. Instead of (even while) spitting out unwanted parts, the ailing person takes in, ingests, borrows, something from the outside to enhance his worth; it’s called introjection.

The most brilliant among Freud’s original circle was the Hungarian-born psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi who took great interest in this process. He was not an economist but did pay attention to his patients’ feelings of worth — and why they felt compelled to borrow strength.

Freud said the borrowing is part of human nature in that everyone at some point in life, in some way, feels unequal to what life has set before him, and has to borrow strength. The archetype, Freud said, is when the child “ingests” the father (or some other person in power) to bolster the self; their power is transferred to the borrower.

It’s like Popeye with the spinach; he can’t handle Bluto so he borrows strength from the outer world; the can of spinach is his father.

Every sane being — and that distinction has to be made these days — believes that pain diminishes the value of living and, even when a person has techniques to absorb the pain, he might decide it’s cost-effective to dump it on someone else — there’s a wide spectrum of how people do it.

And though projection connects people, it’s so aggressive that it reinforces the gap between self and other; good and bad; mine and yours; worth and worthless; inner and outer; you and me. It’s where churches develop their sense of hierarchy.

When projection reaches the name-calling stage and then extermination, everywhere the projector looks he sees evil — Paranoia is born.

Alfred Heilbrun, a psychologist at Emory University, et al., had a paper published (in 1985) called “Defensive projection: An investigation of its role in paranoid conditions.”

The last lines of the abstract read, “Process paranoids demonstrated the most idiosyncratic free associations to verbal cues suggesting the autistic (self-preoccupied) quality of their thinking and delusions.”

Which I translate as: Projecting paranoids become so divorced from reality that a password can set them off; “most idiosyncratic free associations” means folks are willing to deny the physics of their being to live psychotically autonomic lives.

Years ago, the sound of “Hillary Clinton” produced, “Lock her up!” On Jan. 6, there was “Hang Mike Pence!” and “Kill Nancy Pelosi.” Psychotically autonomic responses.

Great power-projector-players like Donald Trump are well-schooled in how to shape autonomic Pavlovian responses; they know how to foster a shift in consciousness where the only choice is A or B, the same choice facing those contemplating suicide.

By “the autistic (self-preoccupied) quality of their thinking and delusions” Heilbrun and his colleagues are saying that the cognition network of such people is a form of autism.

Two great 20th-Century French philosophers — Gaston Bachelard and Jean Hyppolite — were interested in the cause of this, Bachelard in his “La Poetique de l’espace” (The Poetics of Space).

Their thinking was: “Le premier mythe” of humankind is “du dehors et du dedans” and our aggression toward each other “se fond sur ces deux termes.”

Which I translate as: When we accept the difference between you and me as unbridgeable — dehors et dedans — alienation is born, and why so many people in the United States go nutso these days with guns; bullets are the only words an A or B option offers. Suicide is homicide inverted; homicide is suicide projected.

The United States of America is a very sick puppy. I wonder if we’ll ever find a couch big enough where we can all lay ourselves down and confess our sins therapeutically.

In two recent columns in The New York Times, Tom Friedman says the War Between the States: II has begun.

He must have been reading about the end of the Roman Republic when, on election days, armies flooded the forum — a very scary time, and very sad — and very much like today.

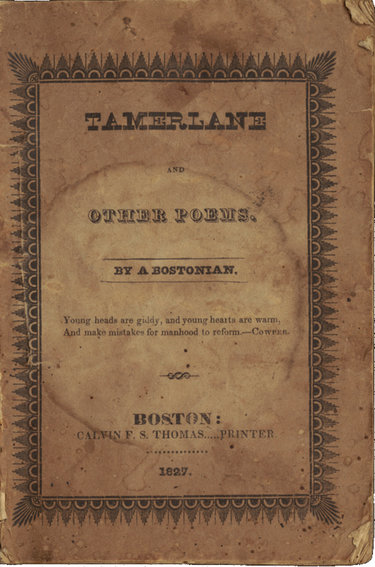

— From Cornell University

Only about 12 copies of “Tamerlane,” the first published work of Edgar Allan Poe, are known to exist. This is the most recent one found — in 1988 in a New Hampshire antiques sore, purchased for $15. It is now in the Susan Jaffe Tane Collection at Cornell University, the largest privately-owned Poe collection in the world.

At the end of February 1988, a Massachusetts man, a fisherman — who would not be identified — came upon a copy of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Tamerlane and Other Poems” in an antiques barn in New Hampshire. He had been looking through stacks of ephemera — pamphlets, catalogues, and the like — and there was “Tamerlane.”

The man recalled having read about it and thought it worth something. At the time, he told The New York Times, “It rang a bell in my head. I was alone. I got very excited.”

It cost $15.

The next day, he was off to the Sotheby’s office in Boston, book in hand, to ask the staff of the elite auction house what they thought. They said he had a gem; in March, they were telling reporters they thought the book would bring in the many high thousands.

In June, “Tamerlane” came up for sale and went for $198,000, dirty cover and all; it has a ring on it as if someone used it as a coaster.

The buyer was the well-respected New York City antiquarian book specialist James Cummins. He never flinched at the price; he said he already had it sold.

Cummins is among those book specialists around the world who view “the book” as a cultural artifact, a work of art, and the more unique the work — limited signed first edition, jeweled cover — the more a certain subset of book-lovers are willing to pay big prices for it — to a known dealer or a scout who found it in an attic or barn, like the fisherman — but they know what they’re looking for.

Almost as if to defend that genre of bibliophile, the artist/writer Maurice Sendak said, “There is so much more to a book than just the reading,” which explains the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School. There, they offer courses like “Introduction to the History of Bookbinding,” “The History of the Book in America, c.1700–1830,” and “The Handwriting & Culture of Early Modern Manuscripts.” Twenty-two hours of class cost $1,000.

But there is another subset of book phile, says the late A. S. W. Rosenbach — considered the greatest antiquarian bookseller of the 20th Century — whose members are taken over by circean lust. In his semi-autobiographical “Books and Bidders” (Little, Brown, 1927), Rosenbach says he had “known men to hazard their fortunes, go long journeys halfway around the world, forget friendship, even lie, cheat, steal all for the gain of a book.”

Cummins, Rosenbach, Tamerlane, and every facet of the rare and antiquarian book trade are presented in D. W. Young’s recent (March 2019) enchanting documentary “The Booksellers,” available on Amazon Video.

Greats from the antiquarian book world show off gems like proud parents. They describe the psychology of what hooked them as well as that of collectors who live for “the find.” But everyone in the movie is so disarmingly honest, they seem like simple monks. They have no filter.

Of course they’re involved in a business but their fascination with and love for books govern their being. It would not be the same with baseball cards.

They know everything about a particular title or even the entire oeuvre of an author: the editions of each book; the paper quality; the stitching of the binding; cover-design; even the watermark — the image a paper mill presses into each sheet that’s (mostly) unnoticeable until you hold it to the light. Today, it’s mostly the company’s logo or percentage of rag in the paper.

For my graduate degree in classics (Greek and Latin), I had a course where we spent considerable time examining the watermarks of atlas-folio-size sheets hung on a line the teacher strung across the room. [A Jesuit from Fordham.] [I could not get enough.] [I was in my twenties.] [Giant sheets of Gregorian chant.] [Incunabula.] [Appreciation of the beauty of the package words come in.]

I’d recommend “The Booksellers” to every booklover there is, but I do not because there are so many strata in the category of “booklover” today.

I know readers of Danielle Steel and James Paterson who say they love books. I know people who read Orwell’s “Homage to Catalonia,” Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath,” Susan Sontag’s “Against Interpretation,” and John of the Cross in Spanish and say they love books.

And I know, and have met those — I owned a used-books store once — who lust after jeweled bindings and first editions and say it’s because they love books — the text incidental.

I suppose the crooks who made off with the great Gospel of Columbkille in 1007, its cover bedecked in gold and jewel, considered themselves booklovers too. But when the tome was recovered, the gold and jewels were gone — the crooks hadn’t read the words within.

The cognoscenti say “Tamerlane,” 40 pages long, was expensive because it came out in 1827; only 50 copies were made; it was Poe’s first work; he wrote it as a teen. And only a cognoscentus would know it was by Poe because the author page lists the poet as “a Bostonian.”

For those who like the money part, in 2009 Christy’s sold a copy of “Tamerlane” for $662,500. It was the most ever spent for a book of American literature; James Cummins called it a “black tulip.”

I love books; I’m not a collector but I buy only cloth, and those fitted with a jacket; I want to know how the publisher depicted the author’s vision.

I also look at the paper quality of a book; I consider how the binding’s stitched; I assess the index, and how easily the print sits on the page; I love words, and especially those clothed in beauty.

For some time now, a cadre of booklovers have been saying they fear the book is done for. They point to computers, Kindle, Facebook, and other paperless engines of information. They say the physicality of a text, the turning of pages — and how such a simple act allows for a second of reflection — are anachronisms.

I used to hear people say, “I’m gonna curl up with a good book tonight,” which I took to mean they were going to create a space in which they and the author would sit in a kind of bubble and converse about life — no interruptions — and explore — when books are at their best —issues of human redemption.

People say they love movies and TV because they allow for escape. But the book, thick with pages and a cover of record, does the opposite; it asks the reader to engage the world, and intimately; even with Dashiell Hammett’s “The Thin Man” somebody’s got to find out who done it.

The saddest thing about the book’s lessening presence in our lives is that reflective reading is passing as well; those words, sentences, paragraphs, whole texts that encourage a person to find his purpose in life, sit on the shelf.

For centuries, Christian monks have called reflective reading lectio divina — texts that move a person to assess what he does for others, how much joy he creates, whether he helps to relieve pain and suffering — it’s really lectio humana.

Such reading requires time-away, a break from the day, a time and place to sit and think and ponder — curl up, as some say. You cannot buy a spiritual life.

In “The Booksellers” the three daughters of Louis Cohen, the late founder of the great Argosy Books in New York City — Judith Lowry, Naomi Hample, and Adina Cohen — appear as angels. I hope they live the way I think they do; then they’d be poets too.

If you’re a booklover who can look in the mirror and say: I want to know all there is to know about books, Ms. D. W. Young made “The Booksellers” for you. As they say in French: Point!

“You like tomato and I like tomahto” is how a line in the old Gershwin brothers song goes but, pronunciations aside, all a good gardener cares about is seeing a slice of a big fat red juicy tomato, with a touch of salt and mayo, spread across a slice of white bread.

It’s a summer thing in the Northeast that I put atop the gardening experience which includes, of course, growing the big fat red juicy things in the first place. Good gardeners are drawn to the process like moths to a flame.

But good gardeners never rush, gardening is a delicate art that requires novice and aficionado alike to find out all that’s known to produce the best-tasting tomato there is.

I always say, if you go to Webster’s, right under “tomato” you’ll find a picture of a good gardener showing off a gem that defines “tomato-taste.”

I know gardeners who make fun of the homeowner who says, “Well, I guess I’ll throw a few tomatoes in this year” but good gardeners welcome anyone into the fold who plants something in the earth and cares for it till fruition. And tomato-loving gardeners are a genus of moth who take to the flame with abandon.

Every year for many years I start tomato seeds indoors on St. Patrick’s Day in hard plastic trays whose cells I fill with the best potting soil available.

I love the day because it’s the beginning of the gardening season, but I rue it as well because I must father those seeds, help them sprout and, when they reach a certain size, set them in pots so their roots can spread.

When the seedlings are ready to go outside, I put them in the sun for an hour then bring them back in. The next day it’s an hour and a half, and after a week, two hours, then longer in mottled shade until the strips can withstand June’s blaze without their leaves turning white from sunburn.

That is, the good gardener accedes to what nature allows or demands. Acclimating the plants to the sun — called hardening off — is a tomato’s sun-tan lotion.

Because of my dedication to tomatoes over the years, I sometimes feature myself a Johnny Tomatoseed, but Double-A at best because I’ve met Babe Ruth Tomatoseed and Willie Mays Tomatoseed.

They didn’t say so directly but I learned from them that the good gardener’s relationship with the tomato (as with every fruit and vegetable) is an act of health: food-health, mental-health, physical health: gardening rearranges the emotions, it’s an epistemological revolution; the good gardener is a seer.

I’m forever upset that wine drinkers can describe the taste of a merlot with the nouns and verbs of poetry. The same is true for olive oil: floral, grassy, robust, polyphenols, are all part of the patois. Such chauvinism might seem chi-chi but, as with the tomato, people want to know what a fruit really tastes like, the gift nature intended — tomato qua tomato, the Standard of Perfection.

In every seed catalogue I come across, the owners of the company try to provide an accurate description of each variety they sell. There are thousands.

No company wants to be seen as a three-card-monte grifter in its sales pitch. They say what science says: The biology of genetics but also the biology of the tongue, the gustatorial judge of that big fat red juicy slice (maybe with salt and mayo) as it slides into the mouth.

That is, with their window-shoppers the catalogue-makers are sharing what the tongues on the street are saying. A few hyperbolize but there’s never a need for caveat emptor.

If I were to use the old man-on-the-street-interview technique — with respect to a tomato — I’d say to the next guy who comes along, “Sir, we’d like you to try this tomato and say in your own words what you think. What are your nouns and verbs? A little salt and mayo maybe?”

The catalogues describe a variety’s sweetness and acidity, how the plant responds to diseases, and how many rosy red jewels to expect in a season. (Some varieties are stingy despite the love.)

A phrase often used with tomatoes — and good gardeners listen — is “old-fashioned flavor” referring to the way tomatoes tasted before agribusiness butted in. Old-fashioned-flavor is a dog-whistle good gardeners can translate.

For example, page 10 of the 2021 Tomato Growers Supply Company’s seed catalogue says of the “Rutgers” — a lost treasure now back in favor — that gardeners everywhere are “rediscovering this old-fashioned classic for its terrific flavor and productivity.”

It says the “Rutgers” is “bright red,” disease-resistant; its skin doesn’t crack when it rains; and has that “delicious old-time taste.”

Old-time-taste means old-fashioned-flavor, which means the taste of the tomato on the vine or a few hours later spread across a slice of white.

On page 6, Tomato Growers describes the “Abraham Lincoln” as “old-time” with a “fair amount of acid … nicely tempered with sweetness” and “packed with great tomato flavor.”

I’ve read hundreds and hundreds of such descriptions over the years but I’d like to introduce you to — to stay with the idiom — the Willie Mays of tomatoes: the “Dester’s Amish.”

There’s a story behind how I got the seeds from Missouri farmer, Larry Pierce, who told me in an email once that “Dester’s Amish” was the greatest tomato he tasted in 50 years.

What a dog whistle.

I got the seeds, I planted them, and every year I share strong “Dester’s” seedlings with family and friends; I turned on the tomato-guru, the late Carolyn Male, to “Dester’s” which is saying something.

A local better-than-good gardener, Don Meacham, told me “Dester’s Amish” is his Willie Mays.

I went wow, when Willie first came up in ’51, when few knew who he was, after a game I walked across the Polo Grounds parking lot beside him, then up a steep flight of stairs (110) that led to Edgecombe Avenue as my father waited below.

I have to agree with my gardening neighbor: “Dester’s Amish” is Willie Mays. How many get to have two heroes in a lifetime?

And there’s still time to get to the ballpark.

Dedicated to Alan Kowlowitz

Years ago, when I was putting together a book on Voorheesville, New York — the small upstate village I live in — I scoured every text I came upon to find its “founding fathers,” of course, but also, and especially, to see if there were citizens who helped transform the “place” into a community.

That is, had the people of Voorheesville developed a shared identity, what sociologists call “a sense of community?”

I also wanted to see if there were souls who urged the community to adopt an ethic of mutual aid whereby every person in the newly-incorporated-self would stand by every other when times got tough.

Such people are able to foster an appreciation of living together that’s bigger than neighbors shopping at the same store, having kids in the same school, or using the same garbage-disposal service.

The government of the village of Voorheesville published the results of my efforts in 1989. Mayor Ed Clark, and especially trustees Susan Rockmore and Dan Rey, had a keen interest in their constituents knowing about their forebears. They saw it as an act of communal health.

They believed people show greater respect for the place they live in if they know who lived in their house 100 years before, or shopped in the same stores downtown — though every store in old downtown Voorheesville is gone now.

For the bibliophiles in the ranks, the history book is called “Voorheesville, New York: A Sketch of the Beginnings of a Nineteenth Century Railroad Town.” It’s a 180-page, 8 by 10, loaded-with-graphics (photos, maps, and store-ads), serious narrative about how Voorheesville became a thriving railroad town and assembled a collection of energetic souls who developed a common purpose. Every page is based on primary sources.

I think it’s sad so few Voorheesvillians I’ve met over the years have shown an interest in the roots of where they live, in how our 19th-Century Victorian counterparts morphed from a collection of people living near each other to a “people” with a vision.

The place had a downtown with four grocery stores, a butcher shop, a funeral parlor, a factory that made quality cigars, a shirt-making operation, and a tomato-canning plant whose tins were shipped from the station daily.

Frank Bloomingdale — our first mayor — sent tons of hay and straw to Brooklyn and Boston; there was a coal business, a grain manufacturing plant, a slate company where the Cummings brothers peddled bluestone hauled down from Reidsville.

The place had two foundries, one a major leaguer. Its owner, Frederick Greisman, was a visionary; he built 10 houses on North Main to attract middle-managers; he underwrote the first library; started a bank — the Voorheesville Savings and Loan Association — where he made his sweat-filled laborers deposit their paychecks before hitting the saloon on the way home.

Mott’s apple juice had a plant on Grove Street where hundreds of workers pressed apples in the fall for quality cider and vinegar and later made jellies and prune juice encased in a beautiful green bottle.

The place had three hotels and dozens of B&B-type operations that each year graciously welcomed families to stay the summer; eat home-cooked meals; and, when the sun got hot, sit beneath a tree or head to the Vly to watch its 100-foot waterfall crash upon the shore.

One of the hosts, Mr. William Relyea, held a kite-flying contest on Saturday nights so his guests could try to reach the Helderbergs with string.

Every year, regional teacher groups returned to the village to hold their annual conference, most often in the social hall of the Methodist Church on Maple, whose congregation offered warm Voorheesville hospitality.

The Grove Hotel had a baseball diamond out back, a race track, a picnic area, and a bandstand where thousands — literally thousands — came from the surrounding cities to eat oysters, drain a tin of beer, dance, and watch a Fourth of July fireworks show.

Albanians could jump on a train and three stops later be sitting on the porch of the Grove — 100 yards from the track. So many newlyweds came to share marital bliss in one of the 35 rooms upstairs that folks called the place Honeymoon Hotel. (The Blue Book for 1886 says rooms were $1.50, guests having the option of the European or American plan).

And the Grove had culture. Its boarders — and any villager who stopped by for a beer — might catch on a given night the vaudevillian Madame Celeste doing her bird and musical instrument imitations. When the weather got warm they headed outside to see Howard’s Big Show, Doctor Gray’s Wonderful Wonders, and the Great New Orleans Show — all from the old vaudeville circuit.

Across the tracks was the equally-famed Harris House, run by my favorite Morris Harris, whose guests could catch semi-pro wrestling one night and the next, the grand vaudevillian ventriloquist Professor Button.

But with so many folks moving from place to place these days — COVID has slowed it — I understand why people show little interest in the place they live in. They’re from somewhere else heading to some other somewhere else — why bother with in-between?

As the official historian of the village of Voorheesville, I’ve attended conventions with municipal historians from around the state who came to learn new things about New York’s history but also to share the story of the place they were from.

I always wanted to know: Did they live in a “place” or in a “community?” Was there mutual aid? How would they describe it? And did their research include how benefits and burdens were distributed?

I had a chance to answer these questions myself somewhat when our regional library system a few years ago created a contest — they called it a challenge — whereby every patron of its 36 libraries was invited to visit every place in the system within four months. Library-lovers saw it as an offer they could not refuse.

And to show that they visited all 36, they brought along a master sheet they got stamped at every stop. I did the 36 in four days.

Moving at that pace, my conversation at each stop was brief but I kept looking at how each library’s shelves were stacked, what the sitting area looked like, was anyone at the reference desk, and how the person stamping my sheet viewed my interruption.

Like a mantra I kept asking: What does this library say about the town? Is it a place or is it a community?

At every library I came to, the staff were excited about the contest and every librarian who welcomed me offered a ready smile.

At the Berlin library, after I got my sheet signed and was heading toward the door, the librarian at the desk, a middle-aged woman, asked in a kind and friendly tone whether, before I left, I might like to use the restroom. Her sincerity was overwhelming.

In Poestenkill, as my sheet was being stamped, the librarian asked if this was my first time there. When I said yes, she brought out from beneath the desk a small paper gift bag with handles that contained a mini-bottle of water, a mini-bag of popcorn, and I think there was a chocolate.

I said: Wow, Poestenkill knows hospitality. It must be a community.

And because at different times I’ve worked with historians from our county, I rooted for all the towns and villages they came from; they are Voorheesville’s neighbors.

And neighbors of The Altamont Enterprise as well. As its editor, Melissa Hale-Spencer, has said, “We try to hold up something to the community that reflects it, and we try to shine a light in dark places . . . And just because you’re small in terms of circulation, doesn’t mean you can’t be big in the sense of the issues that you tackle or look at critically or in a way that sheds light on whatever the particular problem is.”

Hospitality, a sense of community, in print.

During Mel Brooks’s revelatory interview with Conan O’Brien on Conan’s spectacular TBS series “Serious Jibber-Jabber,” the two comics start talking about the comedic greats of 20th-Century America and quickly agree that comedy and Jew(ish) were one. (Any soul into comedy knows it’s true.)

But then Mel turns wistful, sounding like someone who lost something or hadn’t measured up to expectations.

He tells Conan that, when it comes to putting words down on paper, nobody beats the Irish. “Between Juno and the Peacock or Sean O’Casey, just between Beckett and maybe Yeats,” he goes, “I mean when I discovered that these were all Irish writers, James Joyce, the best fucking writers in the world ….”

But then he adds that, when he saw that none of those great writers “was a Jew, I just had a nervous breakdown ... I cried for about a month.”

It’s a most interesting cultural statement but this is no time to psychoanalyze Mel Brooks. Suffice it to say he said the Irish have a way with words and put them down on paper well. He called them “the best fucking writers in the world …. ”

Conan — whose face is the map of Ireland — shows reverence for Mel throughout the interview, despite disparities, working with the advantage of a cultural overview. (Parenthetically, neither mentions that, when the Irish start with that sweet Gaelic lilt of theirs, they’re spinning a web, often of Brigadoon. The truth must be ferreted out.)

Because of his penchant for the Irish tongue, I hope Mel (he’ll be 95 in June) has seen the new book of the Dublin-born writer, Brian Dillon, out last September. It’s called “Suppose a Sentence,” a line Dillon took from Gertrude Stein’s poem “Christian Bérard.”

Stein’s line struck Dillon because he had “supposed” sentences for years, that is, had collected every great sentence he came upon in his reading — those that knocked him out. He jotted them down in the back of his writer-notebooks, which came to 45.

For Dillon, the sentences were objets trouvés, found things, which he wanted to share with the world the way Marcel Duchamp shared the things he found through art: an ordinary snow shovel becoming “Prelude to a Broken Arm.”

Dillon went through all the notebooks and picked 27 sentences he wanted in his Hall of Fame, then created a plaque for each in the form of an essay explaining why the player deserved to be there. The essays reflect a deep anarchic discipline.

As we might expect, Joan Didion, Janet Malcolm, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Susan Sontag — the murderers row of 20th-Century American literature — all have a plaque in Dillon’s Hall. Ironically, there are only three Irish — two women and Beckett. Nine are Brits and 10 are from the States.

To show what Dillon got enthralled with, here’s his sentence from Elizabeth Hardwick:

“In her presence on those tranquil nights it was possible to experience the depths of her disbelief, to feel sometimes the mean, horrible freedom of a thorough suspicion of destiny.”

It sounds like a script from film noir posing questions for Hardwick not only about what she means but also about the oxymoron “mean, horrible freedom.”

The “her” in the sentence refers to the grande dame of the American blues-soul-jazz scene, Billie Holiday, who hip-music-folk know had a fondness for (government-banned) intoxicants.

As the soulful songbird lay dying in a hospital from pulmonary edema and heart failure, at 44, a gaggle of narcs barged into her room, searched her and her bed, handcuffed her to the bed, then stationed two mugs at the door: for what? To snag a dime bag from a nickel-and-dime connection from 125th Street? They found a stamp of smack in her room which they planted there — as she lay dying.

You can understand her disbelief and “the mean, horrible freedom of a thorough suspicion of destiny.”

Hardwick’s sentence is so beguiling the reader wants to lay Holiday down on a Freudian couch and ply her with questions of destiny — but Dillon doesn’t go there, he stays with Hardwick’s writing.

He says of her sentences, “There is a sense always that Hardwick’s sentences stand alone, pay little or no attention to one another, that each is self-involved and sufficient whole.”

Hardwick would’ve loved that, knowing how hard an art it is. It’s like listening to someone say one thing, a minute later the opposite, and then something new, while managing to convey meaning through a cohesive narrative the listener wants more of.

Dillon then turns to Hardwick’s view of her calling: “To wake up in the morning under a command to animate the stones of an idea, the clods of research, the uncertainty of memory, is the punishment of the vocation.”

I fully understand what this means but it’s Emily Dickinson’s loaded gun. “Command?” Who’s commanding? Was not the author in charge?

And to use “punishment” to whine about the price for doing the work one loves — maybe she was tired of her craft or feared she had no more to say.

As a writer for a small-town paper I suppose sentences all the time. Indeed, I juxtapose, interpose, even repose them, while I impose upon myself the rigor of exactitude.

Many years ago one of my teachers used to quote Francis Bacon: “Reading maketh a full man; speaking a ready man; and writing an exact man.”

I took it to mean that the serious reader develops confidence enough to speak to others without resorting to violence; the ready-man’s ideas are well-thought-out. And when he puts them down on paper he’s exact, refusing to speak in abstractions. The full man is gentil.

Violent language is the language of abstraction; it plagues those who refuse to examine their beliefs and thus never get to develop the words, vocabulary, idiom, to speak in sense-tences. The worst among them mouth a fascist babble.

In one of her essays, Annie Dillard tells a story about “a student [who] grabbed hold of a writer and asked: ‘Do you think I could be a writer?’”

The writer, not knowing anything about the person, says, “I don't know. . . . Do you like sentences?”

And with that the writer “could see the student's amazement. Sentences? Do I like sentences? I am 20 years old and do I like sentences?”

Dillard says, “If he had liked sentences, of course, he could begin, like a joyful painter I knew. I asked him how he came to be a painter. He said, ‘I liked the smell of the paint.’”

How sad that today so many despise the smell of the paint of exactitude. For Irish writers — despite all the talk of Brigadoon — exactitude is second nature. That’s what Mel loves about them and why he and they share the same Hall of Fame.