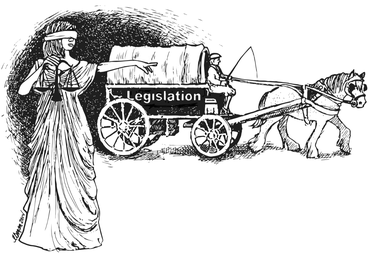

The law is in the hands of the people’s representatives, where it should be

Our state’s top court is wise to recognize its role as distinct from that of lawmakers.

Linda Greenhouse, who covered the United States Supreme Court for decades for The New York Times, wrote in May an opinion piece in The Times critical of the current court’s majority driving it into dangerous territory. “The problem is not only that the court is too often divided,” she wrote, “but that it’s too often simply wrong: wrong in the battles it picks, wrong in setting an agenda that mimics a Republican Party platform, wrong in refusing to give the political system breathing room to make fundamental choices of self-governance.”

That last tenet is critical to a properly functioning democracy.

Two cases decided recently by the New York State Court of Appeals, which had implications that hit close to home, show how that court allowed breathing room. Both cases — one on hydraulic fracturing and the other on cyberbullying — were decided with the same 5-to-2 split.

When the gas-drilling case was argued — to determine whether local laws prohibiting gas extraction trumped state law — the chief judge, Jonathan Lippman, concluded the session by saying, “...You don’t have to bulldoze over the voice of the people in individual municipalities who want to be heard about how they live their lives. So, I’m not taking either side. What I’m saying to you is, we get it, we get your policy arguments, and we get their policy arguments, too. The question which we have to determine — what did the representatives of the people who ultimately have that power actually do? — and we’ll try to make that decision.”

What the court ultimately decided, in an opinion written by Judge Victoria A. Graffeo, is that the state’s Environmental Conservation Law does not preempt local zoning laws prohibiting gas and oil activities within town boundaries but, rather, relates to the regulation of how it can occur.

In the cyberbullying case, a 2010 law passed by Albany County, criminalizing cyberbullying was tested when, in 2011, a then-15-year-old Cohoes High School student was arrested after posting online pictures of 10 classmates with derogatory and sexual comments.

During oral arguments, Lippman’s first question to the New York Civil Liberties Union lawyer was, “Why can’t the statute be salvaged even if there are some things wrong with it?”

Similarly, he asked the county’s lawyer, defending the statute, “It’s possible to save this statute?”

When the lawyer answered, “Absolutely,” suggesting the law could be modified, Lippman went on, “Is that the job of the court...or is that the job of the legislature?”

Later in the arguments, Lippman asked, “Why doesn’t the legislature go and pass another statute that’s tightly drawn?...I think you’d agree it’s not the best statute in the world by anyone’s imagination...Why are we doing this?”

“Marquan committed a crime and should be punished,” responded the county’s lawyer of the 15-year-old who posted the derogatory comments.

“If you can find the crime,” rejoined Lippmann.

Ultimately, the top court, in a decision written by Graffeo, determined the county’s law criminalizing cyberbullying is “overbroad and facially invalid under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.”

Graffeo states, “The doctrine of separation of governmental powers prevents a court from rewriting a legislative enactment through the creative use of a severability clause when the result is incompatible with the language of the statute.”

She notes, “It is undisputed that the Albany County statute was motivated by the laudable public purpose of shielding children from cyberbullying.” But, she states that the “judicial rewrite” to do that encroaches on the authority of the legislature.

So, again, we commend the Court of Appeals for not using its interpretive judicial power to create law.

In both cases, the responsibility is now returned to the lawmakers.

As these cases closely affect the towns we cover, we have some advice for those lawmakers.

With hydraulic fracturing, the southwestern corner of Albany County lies over the gas-rich Marcellus shale formation although prospects for gas are much greater in the state’s Southern Tier. All four Helderberg Hilltowns have cautiously progressed towards addressing hydrofracking, remaining uncertain about what the state will decide; Guilderland, which does not lie over Marcellus shale, has banned the process.

We urge the Hilltowns to legislate against hydrofracking now that the state’s top court has assured their power to do so. Such a ban, which requires careful writing, will protect water and property values.

The larger power, though, lies with the State Legislature; the Court of

Appeals’ decision shows that the legislature alone can override the home-rule power of local zoning laws. We urge our state representatives to create a blanket ban so that New Yorkers’ protection is not piecemeal on a town-by-town basis; the health of all New Yorkers and the environment at large should be protected.

Political reality being what it is — with the Democrat-dominated Assembly opposed to fracking but the Senate not so much — we fervently urge no exemption be passed to thwart the hard-won home rule.

On cyberbullying, the representatives we are addressing are those in the Albany County Legislature. We spoke with Albany County Executive Daniel McCoy on July 1, the day the decision was handed down. He said he hoped to have a new cyberbullying law in place within four to five months.

Not so fast, please. We urge our legislators to stop and think deeply before they hastily pass another similar law.

“We are trying to keep children from harm,” McCoy told us.

Like the court’s majority, we believe this is a laudable aim.

But what is the best way to go about it?

During the oral arguments, Judge Robert S. Smith, one of the dissenters in the case, stated what many of us feel. “I’m just having an intuitive problem with the idea there is a constitutional right for a 15-year-old boy to treat his classmates like this,” said Smith.

“There’s a constitutional right to be free from arrest for treating your classmates like this,” the New York Civil Liberties Union lawyer responded. “But there’s not a constitutional right to be free of consequences for it.”

That is an important distinction. Lawmakers should ask themselves: What are the most effective consequences for a minor who bullies electronically — jail time and a large fine or community service and a meaningful apology?

County lawmakers believed they were filling a void when they passed the law in 2010. That was before the state’s Dignity for All Students Act in 2012 added a provision to prohibit bullying through electronic communication; a local law is not only redundant but counterproductive.

The arrest of four Guilderland High school students this year — the only cases besides the one that made its way to the top court — illustrate a useful alternate route of consequences.

The four juniors, all males, had made a five-minute rap recording, called “Guilderland Sophomore Rap,” naming sophomores, mostly females, at their school, making vulgar and sexually explicit comments about many of them. The rap was posted on Nov. 11 and removed the next day by one of the students who posted it.

While the Guilderland Police held a press conference announcing the names of the students arrested on misdemeanor charges, the school district declined to name them. A lawyer representing one of the Guilderland teens, Joseph A. Granich, said that, separate from the court proceedings, the school district, independently, had held its own hearings and set up sanctions for the students, such as community service, which the students had satisfied.

“Oftentimes, kids make mistakes,” Granich told us. “Those mistakes are dealt with differently today. People are too quick to resolve them in the court system, which has long-lasting, unfortunate effects...I’m not minimizing bullying but this leaves a blemish for life for a mistake you made at 15.”

The county’s lawyer argued that the Court of Appeals could modify the law to make it apply just to minors. When the top court rejected applying this “judicial rewrite” to the law, it gave our legislators a chance to re-think the way they will deal with minors.

Laws prohibiting true threats like harassment and assault already exist.

“Schools are overburdened,” McCoy said. “They try to be all things...They need help. Parents need help.”

Passing a law that criminalizes a minor’s conduct is not the best way to help parents, or schools, or kids. Consequences that teach lessons are a better way to raise responsible, productive citizens.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer