The secret garden of Altamont

The newsroom was churning one Wednesday, our production day, when we got a call, insisting that we come see a garden.

A garden? On a Wednesday?

We already knew we’d be up around the clock twice and attempted to decline. The voice was pert and persistent.

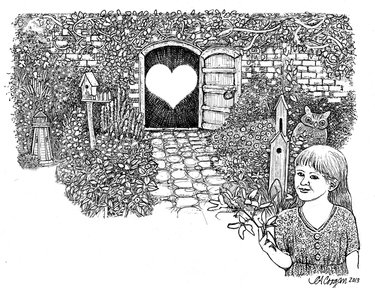

“It’s like a secret garden,” said Rose Ann Rogers.

That did it. She had us.

We made the time to go to Altamont Oaks. And we were not disappointed.

We had loved Frances Hodson Burnet’s novel, The Secret Garden, since we were young. We remembered snuggling with our own children at bedtime to read the story and wanting to never put the book down.

As we rushed to see Altamont’s secret garden, camera in hand, we thought of the spoiled, sour-faced little girl, Mary Lennox. She grew up in wealth in India at the turn of the last century, the only daughter of a British couple. When cholera killed all the adults in her household, she was sent to Yorkshire to live with her uncle at Misselthwaite Manor.

There, again, despite the wealth, Mary was neglected. She discovers a sickly boy, just her age, Colin, shut away as an invalid since his father, Mary’s uncle, is remote in his grief over his wife’s death. Mary discovers a secret garden at Misselthwaite. As she and Colin tend it, with the help of a kind servant’s son, Dickon, they flourish as surely as the flowers.

We had driven from our home to the newspaper office hundreds or even thousands of times and never looked inside Altamont Oaks. When we turned off the boulevard, we discovered what might be called a secret courtyard. Bordered on three sides with apartment buildings, the center space, no doubt intended for cars, was vibrant with kids at play. No one had the sickly look of Colin or the sour look of Mary. They were happily skipping rope or riding bikes.

At the far end of the complex, Rose Ann Rogers sat with a cluster of friends on her front lawn. She took us behind the complex to see the garden, her face shining as she pointed to a bright orange blossom on a vine her friend had grown.

It was hard to take in all at once. The garden stretched like a wave along the back border of the property. The plants were varied and lush; interspersed along the garden’s length were charming tableaux, vignettes that seemed almost other-worldly: a small wooden bridge with an owl standing guard here; a lighthouse standing like a beacon there; further down, a trio of quaint birdhouses; and still further, a gazing globe on a pedestal with a metal pheasant at its foot.

The love and care that went into the garden was visible at every turn, but it wasn’t until we returned on a later visit to meet the gardener, Yvonne Lustenhouwer that we understood the depth of love that had gone into creating her living work of art.

“It’s almost like a memory garden,” said Lustenhouwer. She pointed to some bushes and said they were there in memory of a neighbor who said to dig them up as she was dying of cancer.

A well-worn duck statue belonged to another neighbor, Melvina Gifford, who died recently. “I said to her children it will have a place of honor in the garden,” said Lustenhouwer. She and her friends talked fondly of the woman they call “Melsy” and said how much they miss her, with Lustenhauwer describing her as “the glue that made us family.”

We decided right then and there Lustenhouwer and her friends, her Altamont Oaks family, should lead our Home and Garden section.

For years, we’ve featured wealthy estates, historic homes, even a castle. What we found at Altamont Oaks with Lustenhouwer and her friends was the essence of home.

“This place gets a bad reputation because it’s low-income housing,” said Lustenhouwer, “but 98 percent of us take care in making our homes.”

Her garden bears silent and beautiful testimony to that. Creating it took more love than money. The manager helped out with water because the cost was so high, and the neighbors all enjoy it.

Similar to the wisdom that Mary and Colin found in their playmate Dickon, we learned some lessons from Lustenhouwer that went beyond typical gardening tips.

She told us how she gave plants to friends and received them in return. That makes both gardens richer.

She told us, too, about how she loves working in the dirt. It restores her after a bad day, much the way it rejuvenated Mary Lennox. Lustenhouwer didn’t mince words. “My thing in life is to keep active,” she said. “I figure I can lie down when I’m dead.” Good advice, we thought.

Finally, she talked about how impatient her friend Melsy Gifford had been when her daughter gave her a stick of forsythia. Lustenhouwer told her friend, “They’re like children. First, they crawl; then, they walk; then, they run.”

We need to learn that kind of patience, we thought.

Lustenhouwer went on; she told her friend, “In the third year, it will bloom.” Then she concluded, “This year, it really did bloom — and she wasn’t here to see it.”

Well then, we thought, never mind patience; what’s the point?

One of Lustenhouwer’s friends answered our question, although we hadn’t said a word.

“She’s here in spirit,” said the friend.

And the new tenant in Melvina Gifford’s apartment wanted to keep the forsythia bush just where it is.

It blooms like the friendships around it.

The Secret Garden still has its magic.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer