Build on firm ground

Preparedness is the better part of progress.

We were struck at a public hearing earlier this month by comments from a geologist who works for the state museum. Charles Ver Straeten felt his advice for Thacher Park’s first master plan had been ignored. He said that it is unwise to build a visitors’ center so close to the edge of the Helderberg escarpment.

This was the weightiest concern brought to light at the packed public hearing, covered in detail in our Aug. 8 edition. The response from Alane Ball Chinian, the director of the Saratoga-Capital District Region for the state’s Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, was that the visitors’ center was slated to be built “quite a ways from the edge.”

She pointed out that Ver Straeten’s wife runs the nature center at the nearby Thompson’s Lake State Park, which is to be combined with Thacher, according to the master plan. And, she told us, Ver Straeten was opposed to rock-climbing at the park, which the plan would allow for the first time. She surmised that was why he felt ignored.

Setting aside the issue of allowing rock-climbing, we wanted to know about concerns in building a visitors’ center.

Ver Straeten has a doctorate degree in geology and his expertise is a perfect fit with Thacher Park’s geology. His specialty is sedimentary rocks — made of mud, sand, gravel, and shells — of the Devonian period, which ran from 420 million to 360 million years ago.

But Ver Straeten said, as a state worker, he couldn’t talk to the press. We looked elsewhere, starting with Michael Nardacci who writes the “Back-roads geology” column for The Enterprise. Nardacci knew, in general terms, about the karst topography of the Helderbergs. The acid from rain dissolves limestone, and fractures enlarge over time, developing a sort of underground drainage system so that run-off with, say, oil from a parking lot can travel great distances and pollute groundwater.

Nardacci couldn’t comment specifically on the Indian Ladder Picnic Area where the visitors’ center is planned, and referred us to Thomas Engel, a caver who, he said, knew every trail at Thacher and the topography beneath.

Engel, who is not related to Ver Straeten’s wife, the director of the nature center, although they share the same last name, had spoken at the hearing about access to caves in the park and about keeping the historic roads rather than narrowing them into trails.

Engel has visited the park for more than half a century and has mapped its structural geology, recording faults not noted before. He called Ver Straeten’s concern “legitimate.”

Engel described two processes at play in the park: the physical parting of the limestone, and then the dissolving or enlarging of the joints, making the ground less stable.

“The top of the cliff is limestone,” he said. “Limestone undergoes a solutional process, dissolving away slowly….The cliff is marching back westward over time.”

The “zones of weakness,” he said, fill up with flow stone. When these chunks break off, they leave behind a surface that is light tan or yellow. When a large chunk fell off the escarpment in the 1830s, it created what is known as “Yellow Rock” today.

Ver Straeten’s concern, Engel surmised, is that not enough geotechnical work has been done to know the extent of these partings. Indeed, Ver Straeten had noted that, east of Yellow Rock, fractures can be seen from top to bottom and geologists don’t know how much farther that reaches.

The “partings,” Engel said, get water in them, and, over the winter, go through a freeze-and-thaw cycle, leading to collapse in the spring. The concern, he said, is that the weight of a building could “put undue stress on already existing partings.”

He went on, “The faults in the park are old; they haven’t moved in hundreds of years…The issue is the joints.” He described the familiar gaps in the Onondaga limestone on the north side of Beaverdam Road, stating, “It’s no big deal because you’re nowhere near a cliff.”

He continued, describing layers of rock at Thacher Park “At caves, they propagate from the Coeymans to the Manlius. They keep going right down through…You could have a joint that runs the full length of the cliff.”

Engel spoke of “Fat Man’s Misery,” which generations of Guilderland Earth-science students squeezed through on their way to Hailes Cave. “Think about what could happen if that fell off…That’s the cause of concern. We don’t know where the rock will fall.”

The solution is obvious: Study before building. Engel, who has retired from his work as an environmental analyst for the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation, said, “I worked for the DEC long enough to know there’s always a middle path.”

Technical work has to be done to see what is underlying “the skin of the earth,” as Engle put it.

“Are they deep joints?” he asked.

That is the question that must be answered before further plans are drawn for the visitors’ center.

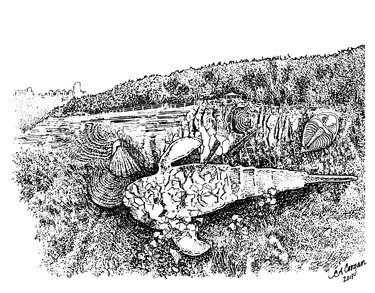

One of the features of the center will be to educate the public about the geology and fossils of Thacher Park — the very thing that has made it an attraction for a century.

Engel put it simply: “Make sure this stuff is being placed in the right location. The technology exists to do that.”

Before the state invests taxpayers’ money in building, we urge such tests be conducted. We fully support a visitors’ center. Educating people about the natural wonders of the Helderbergs is a grand idea, and can be a worthwhile draw.

We just want to avoid the irony and tragedy of an unsafe building for want of secure underpinnings.