The road to a vibrant future is paved with thoughtful planning

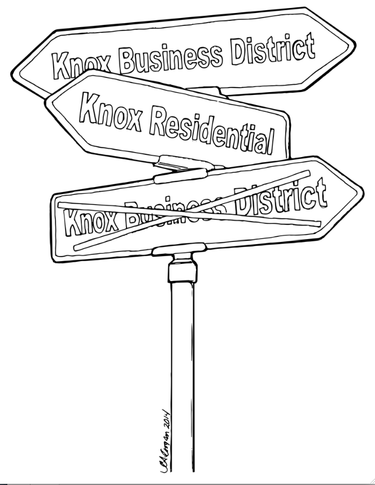

Knox is at a crossroads.

Similar to many other small, rural towns near large urban or suburban areas, many of its businesses have closed. And the Hilltowns won’t be growing any time soon; a regional planning commission has projected that, by 2050, the population of each of the four Helderberg towns will increase by less than 200.

In the 1800s, when most Americans were farmers, before the invention of the automobile, towns like Knox were largely self-sufficient. They had blacksmiths and mills, stores and eateries, churches and schools.

As cities — with their factories and mass-produced goods — grew, there was an exodus not just of people but of services from rural towns. The small, neighborhood schools disappeared as districts centralized and bused kids to large learning centers. Shopping malls, big-box stores, and most recently Internet sites replaced the old general stores.

Knox can’t go back in time to create the more autonomous, agrarian culture it once had. But the town can make plans for a more vibrant future.

Over 20 years ago, the town went through a laborious and worthwhile process, surveying both its residents and its resources to create a comprehensive plan for its future. A revamped version of that plan is long overdue and the town board is currently working on an update.

In order for a master plan to do its job, it needs to take a large view of the town and its future; then that vision needs to be codified into law. And, once zoning laws are adopted, they need to be enforced fairly and assiduously.

The current, burning issue in Knox is its lack of any legally designated business district. The last remaining commercial establishments in its hamlet — a gas station, a general store, and a post office — have all closed in recent years.

The town board has received a recommendation from its planning board to create a business district in the hamlet, a sensible start to creating local commerce that some residents are clamoring for.

The proposal for a second business district is more problematic. The impetus for the district comes from a towing business that was built in a residential zone. Kristen Reynders first ran Hitmans Towing from her family’s home in the village of Altamont, also in a residential zone.

“I am not opposed to people trying to make a living,” wrote a Knower Court resident to the village’s zoning enforcement officer. “However, I did not move to Altamont to live next to a commercial tow business with large commercial vehicle coming in and out all hours of the day and night....” In making the appeal for the law to be enforced, the writer noted he did not wish to get in a conflict with neighbors.

That is one of the reasons zoning laws exist, so that people can expect certain activities in designated areas and don’t have to speak out publicly or fight with their neighbors to see that those parameters are followed.

Reynders then moved her business to Knox where, her real-estate agent has asserted, he was told by Knox’s zoning administrator there would be no zoning problems with a commercial garage. This was never put in writing. As Reynders built her home and her business on the Knox property, she developed a loyal following of residents who were understandably outraged when she was ticketed for a zoning violation.

The ticket appears to have been triggered by her application to expand her business to do state vehicle inspections. But it points to a larger problem. The zoning law is not being consistently enforced in Knox. Hitmans towing or any other business should not be allowed unless it predates the zoning law or has a special-use permit.

The planning board, in split votes, has gone from recommending a business district be designated that would include Hitmans, to rescinding that recommendation, to again recommending it. The latest recommendation created an uproar after town Councilman Nicholas Viscio said that the vote was unfair since, he asserted, planning board members had been lied to.

No one likes to be called a liar. It is fair to say there was a misunderstanding. Some planning board members believed they were to choose the least objectionable of three options submitted by petitioners. Viscio said the town board issued no such directive, as three board members remained silent; their silence implied consent.

The town board should have drafted a written charge for the planning board, on which members voted so that each one’s view was stated. That way, the planners would have had clear instructions on their role.

What the town board did next is equally flawed. In a single resolution, passed by unanimous vote, it agreed both to develop a business district that would include Hitmans but to wait until its master plan is updated.

This is frustrating for the Hitmans supporters because the process could take months. But, more importantly, such a caveat derails the point of developing a comprehensive plan.

A committee of citizens is to work with a professional planner to update the blueprint for Knox’s future. At the very core of this model is the assumption that the plan will be based on an open view and sound principles, not fettered by a promise of a specific district.

Right now, what commerce is at play in Knox is largely under the radar of zoning-law enforcement. The town needs to take a fair look at what currently exists, and then decide what it would like to see in the future, and how best to shape it.

For example, one goal might be to attract visitors to the area, building on a century-old history of tourism when city dwellers summered in the Helderbergs. We know the days of the big hotels that catered to months-long visitors are over, but day trippers could be enticed from nearby cities and suburbs.

The real-estate agent for the recently closed Highlands restaurant in Knox, for instance, noted last week that the property would be ideal for someone who wants to capture the summertime seasonal market. Thacher Park, with its own newly drafted master plan, is partly in Knox and attracts thousands of visitors.

Sound seasonal commerce can sustain small businesses in the cold months when locals make up most of the customers.

So, to continue with our single example, if the master planners were to decide this was a worthy goal, attracting visitors to sustain a local economy, they may well follow the advice outlined over a decade ago in the Helderberg Escarpment Planning Guide. “The aesthetic significance of the Helderberg Escarpment region is so great, and its other resources and limitations are so significant that, in the committee’s view, much of the region merits both special zoning regulations and...(State Environmental Quality Review) of most development activity.”

The plan outlines a “critical zone,” part of which falls in Knox — other parts fall in Berne, New Scotland, and Guilderland — that is “the most aesthetically sensitive and fragile portion” and recommends beginning with 10-acre zoning density in the area.

A second example would be to fulfill the vision of the town as a rural community that still encourages agriculture. This would involve leaving large agricultural tracts around small central clusters for businesses, perhaps mixed with residences.

One Knox resident said at a recent Sustainable Hilltowns meeting, “We would like to have stores and a post office and the necessities of life so that, when we get old, we don’t have to drive off the Hill for every single thing.”

Again, these are just two examples. The true direction is up to town residents to decide, so thoughtfully fill out the surveys that are being sent to you.

No matter the direction, the important part is: Rather than merely reacting to a current crisis, the framers of the updated comprehensive plan should proactively map out the future. Once the big picture is in place, the details — adopting appropriate zoning laws and enforcing them — must follow.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer