Knowing your neighbor is the glue that holds the species together

In the Fall of 1957, the ABC television network aired a new game show, “Who Do You Trust?” It was a follow-up to a show that ran the year before, “Do You Trust Your Wife?”

In the new format the host, a young Johnny Carson, gave a contestant a category of questions and told him he was going to ask a question from it. The man had to decide whether he would respond or wanted to call his wife (waiting off stage) because he trusted her to know that part of life better.

The show could have easily been called: “How Well Do You Know the One You Love?”

Such shows spark viewer prurience because, as the contestant is deciding what to do, the viewer is wondering what he would do in the situation, that is, how well does he know his own wife?

A postmodern version of the show — in societies where people often arm themselves with automatic weapons and head to a movie theatre or holiday party to blow people to smithereens — might be called “How Well Do You Know Your Neighbor?”

Unlike the prototype “Who Do You Trust?” where winners walk away with a few dollars, the neighbor show is high-stakes stuff involving light-flashing ambulances and emergency rooms filled with bloody limbs.

Of course what comes to mind is the mass killing that took place in San Bernardino, California earlier this month when 28-year-old Syed Rizwan Farook and his 29-year-old Pakistani wife, Tashfeen Makik, went to Farook’s place of employment and “took out” 14 and sent more than 20 in emergency vehicles to the hospital to have their discombobulated bodies made whole again.

In terms of a game show, what the families knew about those folks is enigmatic at best. Nobody saw they had lost their minds to the belief that violence is an efficacious problem-solver — called “radicalization.”

If the relatives were on the game show “Do You Know Your Neighbor?” or “Do You Know the Ones You Love?” they’d have walked away with nothing while the community had been assigned the task of picking up mops and pails to wash away the stains of blood.

Farook’s brother-in-law, stunned by the event, said he was “baffled.” He said Farook was a “good religious man,” “just normal,” “not radical”; he and his wife were a “happy couple.”

When Farook’s sister, Saira Khan, was asked whether she noticed anything, her eyes glazed over, so soaked in disbelief was she. She said the couple was married, they had a child!

Feeling guilt over what occurred, she told CBS interviewer David Begnaud, “So many things I asked myself. I ask myself if I had called him that morning or the night before, asked him how he was doing, what he was up to. If I had an inclination, maybe I could have stopped it.”

“Inclination” is the operative word, which means “I knew nothing.” In response to her statements the Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump publically called her a “total liar.”

But the collective’s pool of predictive measures told us nothing either:

— 1. Neither person had a criminal record;

— 2. Neither was on a government terrorist watch list; and

— 3. The government had no concrete evidence (inkling) that something was going on.

Of course in retrospect, when 150 million FBI agents are put on the case, a few critical facts will turn up, such as those folks were engaged in big-time subterfuge (advocating violence as a problem-solver) for quite some time.

Though government officials are not allowed to take part in our game shows, we have to admit the FBI would score high on a show called “We Know a Lot About Your Neighbor — Retrospectively!”

We have to laugh at the “profilers” (sadly) who people the television screen after such bloody events, boldly stating that we need to be on the lookout for this or that. But, if their prediction tables are so good, we’d see scores of suspects being arrested while you’re reading this.

A headline in the Jan. 16, 2015 edition of “The Atlantic” reads: “To Reduce Gun Violence, Know Thy Neighbor” with the tantalizing subtitle, “How a sense of community can help stop a bullet.” The premise, of course, is a truism: If you know the people around you, you have a better chance of knowing what’s going on around you.

The author of the article, Andrew Giambrone, points to a recent study funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program on “neighboring” where the researchers found that a majority of their interviewees said they knew little about what went on in their neighborhood.

Scads of books and articles have been written on the loss of “social cohesion” and “social capital” — “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community” jumps to mind first — the glue that holds the species together, the collective wherewithal we bank on to move us into the future with minimal blood and violence.

With all the talk these days about building walls — physical and psychological — around racial, ethnic, and religious groups we want to keep at nation-boundary length, is it not feasible that members of some communities, worried about whether newcomers into their neighborhood are latently violent, will pay real estate agents to administer a battery of psychological tests to screen out the potentially violent?

If we’re ignorant about the current people we walk among, perhaps we can classify potential neighbors into the “good,” the “bad,” and the “ugly.” A kind of psychological redlining in the interest of building walls around our worries.

In a few hours, the New Year will be upon us. In some quarters, the champagne will flow like mad as revelers waltz across the ballroom floor subconsciously wondering how different things will be in 2016.

Me? I’m going to do two things. First I’m going to sing the traditional anthem, “Auld Lang Syne”:

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and never brought to mind ?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and auld lang syne?

For auld lang syne, my dear,

for auld lang syne,

we’ll take a cup o’ kindness yet,

for auld lang syne.

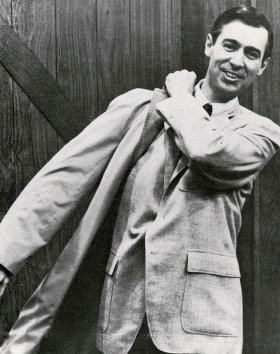

And, while I sing this sad reflective song, I’ll raise a cup of kindness and give thanks for the collective good will and tenderness that have brought us this far. Then I’ll sing a wassail song under the guise of the famed Mister Rogers.

In the cider-producing parts of western England this time of year, neighbors sing and brandish toasts to awaken their apple trees to scare away the evil spirits that threaten loss in the harvest to come. Mister Rogers wassailed every day his program aired in hopes of bringing forth a crop of worthy neighbors.

Perhaps you’d like to sing along with me:

It's a beautiful day in this neighborhood,

A beautiful day for a neighbor,

Would you be mine?

Could you be mine?

It's a neighborly day in this beautywood,

A neighborly day for a beauty,

Would you be mine?

Could you be mine?

I have always wanted to have a neighbor just like you,

I've always wanted to live in a neighborhood with you.

So let's make the most of this beautiful day,

Since we're together, we might as well say,

Would you be mine?

Could you be mine?

Won't you be my neighbor?

Won't you please,

Won't you please,

Please won't you be my neighbor?

Eso es todo, no hay más. ¡Feliz año nuevo!