How does our genetic soup guide us to good or evil?

I have often wondered what it’d be like to be the grandson of George Wallace, the former four-term governor of Alabama.

In particular, I have in mind when he stood in the doorway of Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963, blocking Vivian Malone and James Hood, two black students from getting to class.

Wallace saw it as a way to live up to his inaugural vow: “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” six words that still sit atop the most-ill-famed shibboleths of the 20th Century.

Wallace said those words but they were writ by fellow Alabaman, Asa Earl Carter, a hopped-up Klansman whom the governor hired to write his words. Wallace tapped Carter because Carter knew the kind of violence the governor was attracted to.

The regular Klan had not been good enough for Carter; in the mid-’50s, he started a Nazi-style-shirt offshoot of the group called the “Original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy.” He knew it’d work, he said, because “the mountain people — the real redneck — is our strength.”

Much of that “strength” used to read the Confederacy’s periodical, “The Southerner,” which targeted the weak and the outcast, the sheep who needed a shepherd not a sadist of ridicule and violence. Some of the confederates were ready to take action.

On Labor Day, 1962, six of them — Bart Floyd, Joseph Pritchett, James N. Griffin, William Miller, Jesse Mabry, and Grover McCollough — got lathered up to the point where they needed to “grab a negro,” “grab a negro and scare hell out of him.” That’s what the court record detailing the event says they said.

Newspaper accounts say the “Dirty Six” were riding down Huffman-Tarrant City Road when they saw a middle-aged black man walking with his girlfriend; his name was Judge Edward Aaron. He was a World War II veteran who some said was a bit “slow.” Maybe because of the war.

The mob grabbed Aaron, dragged him into the back of a car, and drove him to a cinder-block hole called “The Slaughter House.” They pummeled him with mockery and then hit him over the head with a tire iron, knocking him senseless.

Then one of the boys took out a package of razor blades, which they’d stopped off to get on the way, and proceeded to cut Judge Edward Aaron’s testicles off. As Aaron lay soaking in his blood, one of his fellow Alabamians poured turpentine of his bleeding self, I’m sure for further pain.

How do some people derive sadistic pleasure from hearing a fellow human-being squeal like a smitten pig — that they’re causing! The six dragged the bloody mess back into the car and, after going a bit, dumped him into a creek bed, leaving him for dead.

But Aaron lived and, when the facts were sorted out, the police took the six into custody. Concerned about their hides, two of the six turned state’s evidence; the other four got 20 years apiece.

But when my imagined “grandfather,” George, became governor, he shifted agency personnel around and the four were set free. Apparently severing the testicles of a black man for personal sadistic pleasure did not deserve a place in the Alabama penal code.

When I think of Wallace as a grandfather I’m overwhelmed with the thought of the work I’d have to do to disengage from my family’s social DNA, a gene that supports purging groups of human beings from the Earth like Nazi soldiers.

What a lot to chew on for a kid who’d like to live a life of justice, who not only does not wish to harm others but supports meeting the needs of every being despite race and creed.

Engaging with one’s social DNA is not a game. People are faced with realities that sometimes breed strange proportions.

When the American actor and filmmaker Ben Affleck found out his great-great-great-grandfather, Benjamin Cole, the sheriff of Chatham County, Georgia, was a slave-owner, he refused to go on PBS’s “Finding Your Roots” because that fact would be revealed to the public.

In another segment of the show, actor Ted Danson, wondering what he would find out, wistfully whined: Oh, please don’t tell me my ancestors were poor! Danson is wealthy but he knew that, if he found out “poor” was in his genes, he’d have to spend time examining the complex.

Social DNA flows from generation to generation like a tiny rivulet and pervades all who follow in the family, leaving each person to figure out the ways those genes drive him or her to ill or good. It’s not a minor matter.

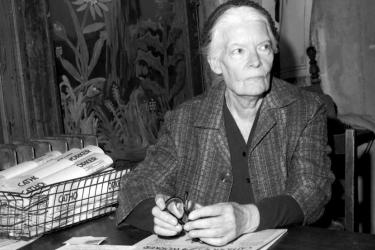

Even those blessed with saints in the family are not exempt. The American writer Kate Hennessy, whose grandmother was Dorothy Day of the Catholic Worker Movement, introduces us to how she faced her derivation from a “saint” in a disarmingly personal way.

In her well-received 2017 “Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty; An Intimate Portrait of my Grandmother,” Hennessy tells us how she worked through the gene of having one of the most revered Catholics of the 20th Century as a grandmother.

Day’s case, as you may know, was put before the Vatican by Cardinal Dolan, the Archbishop of New York, as someone who lived a life of “heroic virtue” and should be declared a saint.

Day had set up Catholic Worker communities around the country — and now the world — that offered hospitality to those in need of food, shelter, and clothing; many of today’s 200 communities in the United States have cots and hot soup waiting every day of the year.

And in almost every case, the Catholic Worker demonstrates against U.S. war policies that take food, shelter, clothing, and know-how out of people’s worth.

Those who come to the Catholic Worker are helped, no questions asked — unless they’re violent. There are no papers to show.

Finding herself “cast” into this saintly milieu — people attending to the needs of Skid-Row America without asking something in return — Hennessy said she felt like an “outsider.” The further you get into her book, the more you see, paradoxically, that she feels like a homeless person herself.

Hennessy reached the conclusion that, being needy herself, she could not attend to the needs of the more-needy, certainly not face-to-face. She looked at the social DNA that came from her mother, Dorothy’s only child, and realized the truth of what her grandmother said: “How little we know of our parents, how little we know of each other and of ourselves.”

Hennessy’s book is not a Catholic book. It’s about her grandmother and the movement she started of course, but it’s really about how a young woman deals with a delicate social DNA that’s part of her being — a DNA that mandates every person is responsible for alleviating the pain and suffering of every other — without a payoff.

Thus Hennessy’s book is for people who wish to examine their social DNA and how their particular genetic soup drives them toward good or leaves them mired in a swamp of violence.

The lifelong task of figuring this out is what it means to have a spiritual life, to being a “practical mystic,” as Dorothy said. And attending to one’s spiritual grounding, she added, requires at least three hours a day.

If you think this is a hard row to hoe, she would agree; she once said, “Love in action is harsh and dreadful when compared to love in dreams.”

If I were to imagine an inaugural address Kate Hennessy were to give today, following in the footsteps of her saintly mother and grandmother, I know I’d hear: “Love today, love tomorrow, love forever.”