Use citizens' energy to further projects

In the last quarter-century, we’ve watched and documented the way dedicated citizens, appointed by elected boards, can move a community forward. Recently, for example, we covered the recommendations made by a facilities committee appointed by the Guilderland School Board.

Citizens along with volunteer staff members and school leaders worked with an architect to sift through reams of data, make site visits, and determine what upgrades would be essential for security and maintenance. Ultimately, two propositions were developed — one with what the superintendent called “the guts” and the other with recommended upgrades to the high-school auditorium and football-field lighting. The voters will have their say on Nov. 14.

It would be unrealistic to expect every resident of the district to know the details or to have the expertise to determine what upgrades are needed. We trust the committee that made the recommendations that the school board adopted.

Of the municipalities we cover, most of them have comprehensive land-use plans. These have taken months or even years to develop, and they form a blueprint for development. The lion’s share of the work, often under the guidance of a hired planning consultant, is performed by committees of citizen volunteers who poll residents and businesses and gather information on resources and services to craft sensible recommendations on which zoning laws may later be based.

In recent years, on this page, we’ve urged the towns we cover in southwestern Albany County, including New Scotland and the Helderberg Hilltowns, which lie over Marcellus shale, to form committees that will make recommendations to their town boards on hydraulic fracturing whereby gas is freed by injecting water mixed with chemicals and sand at high pressure into wells to fracture rock.

It is instructive to contrast the approaches taken by two neighboring towns — Rensselaerville and Westerlo.

John Mormile, who chaired the five-member Rensselaerville committee, wrote in the preface, “An open-minded approach allowed us to sift through reams of data and information, separating available facts from mere rhetoric, and emotion from common sense.”

All of the five members were committed to seeing whether or not hydraulic fracturing was a “match” for the town’s comprehensive plan, which reflects “what the town’s citizens hold as important in our quality of life,” wrote Mormile.

After going over the committee’s charge and the history of natural gas drilling, the report, complete with footnotes that reference the source of materials, takes a careful look at what in Rensselaerville could be affected — impacts on water quality and supply, on property values, on roads and safety, and on community character and quality of life. The report concludes with a recommendation that the town board enact law to prohibit heavy industry, including gas, oil, and coal extraction.

“Any local economic benefit of natural gas development is not likely to outweigh the negative local impacts of the rural quality of life, safety, health, and well being of the citizens of the town of Rensselaerville,” the report concludes, basing that conclusion on the clearly written eighty pages that have gone before.

By contrast, the Westerlo committee was handicapped because the town, as yet, has no comprehensive plan to guide it.

The Westerlo committee of five — although they are not clearly named as in the Rensselaerville report — writes an unsigned introduction that begins, “Numerous townspeople expressed interest in the possibility that the hydrofracking industry would find a financial interest in Westerlo’s subterranean gas resources.” After concerns were raised, a committee was formed, it says, with the foremost criteria for membership being “total non-bias.”

The introduction goes on to say that the committee “was resolved to not make a unilateral decision” on whether to allow hydrofracking in Westerlo. “Instead,” it says, “they chose to provide factual, substantial information for the townspeople to review and decide the direction [to] take…The decision of whether or not to allow hydrofracking in Westerlo will be passed from this committee to our fellow citizens.”

It’s foolish to believe that each of the three thousand or so citizens in Westerlo would independently devote hours to researching hydrofracking and its effects on the town. Besides, state law does not allow for a public referendum on the matter as the town board once supposed.

In short, the committee abdicated its duty.

The report consists of about 140 pages of parts of other documents — much of it from the state’s environmental impact statement, which is itself flawed. There appears to be no correlation between generalized data and excerpts— ranging from statements from the industry to pieces of a congressional report — and the potential effect on Westerlo.

For example, Kathryn Z. Klaber, president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition, is quoted —saying, “Tens of thousands of jobs are now supported by our industry and dozens of sectors — from steel to construction firms — have been revitalized through the promise of clean-burning and abundant American energy” — alongside a 2011 congressional report stating, “Companies are injecting fluids containing chemicals that they themselves cannot identify.”

In amassing random viewpoints, the committee has drawn no conclusions.

Town board member William Bichteman, to his credit, said in July that the report should be revised and, by a 3-to-2 board vote, the board sent it back to the committee. That month, the board also extended its gas-drilling moratorium for another year.

In August, it looked as if Dianne Sefcik — a Westerlo resident who has been outspoken in her views against hydrofracking and against the committee’s secrecy — would be appointed to the committee as it reworked the document. At the August meeting, Bichteman said another committee would be formed to “redo or modify” the report and he had yet to find someone who was for hydrofracking as much as Sefcik was against it.

Sefcik went to the committee’s Oct. 21 meeting — and we are pleased it was an open meeting — but she was not included as one of its members. Bichteman is now saying that, while the committee is open to input, its members don’t want to add to their number. Two of the original five members have quit; the three who remain were part of the scattershot approach of the first report.

That indicates to us it won’t be substantially reworked. And that’s a shame because the current document is useless.

We urge not only Westerlo residents but any who live over Marcellus shale to look at recommendations from the Union of Concerned Scientists, which has developed a toolkit to improve decision-making on fracking, available online.

It recommends — and gives specific recommendations on how to do meaningful research locally — asking questions on water quantity and quality, on air quality, on land use and ecology, on infrastructure, on earthquake risk, on climate change, and on social and economic impacts.

The kit is comprehensive, covering specifics. For example, under water quality, it makes the important point that baseline testing — done before any fracking — is needed to determine later whether the fracking caused pollution.

Sefcik, who moved to Westerlo a decade ago for acreage that was, as she puts it, “clean and clear,” has devoted much study to hydrofracking and wrote in a letter to us of a trip she took to Pennsylvania to look at the effects of fracking there.

“The air quality really surprised me,” she said, noting that it made her eyes water and itch, gave her a headache and sore throat, and made her feel nauseous.

She has given much thought to how fracking might affect Westerlo and would like to see the report include a discussion of the Alcove and Basic Creek reservoirs and how the quality of Albany water might be affected; the effects on the Middle Hudson and Schoharie watersheds; the impact of truck traffic on roads and bridges; the source for the millions of gallons of water the fracking would require; the management of waste, which, she says, “The industry is shoving onto communities”; the effects on birds and animals; and the social and economic impacts.

A committee is the right body to study these matters. We urge Westerlo to reconvene a committee, as the board originally agreed it would, with members willing to do the work to get answers to the questions raised by the Union of Concerned Scientists as they apply to Westerlo.

The state’s top court is now hearing two cases from towns in central New York where gas companies were not deterred by municipal bans, asserting local zoning ordinances would be preempted by state law. The Appellate Division, in two unanimous decisions, ruled that towns can ban gas drilling within their borders.

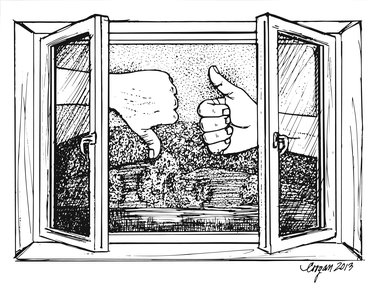

While the state continues to delay approval for hydrofracking regulations, there is a window of opportunity for towns to act.

We implore Westerlo to use that window to assemble a hard-working committee, charged with producing a document that addresses local effects and that makes a recommendation.

Our view is clear and has been stated before: Municipalities must use the power of home rule to protect their citizens from the poison that could pollute for generations to come.

That may not be Westerlo’s view. But right now, the town is like a rudderless vessel; it needs the guidance of a committee that will do its work.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer