Clustering development: More homes, more open space

NEW SCOTLAND — In 1930, about 13 percent of the United States population lived in the suburbs. Then, in the “defining feature of American life after 1945,” millions of returning servicemen traded in their Depression-era memories for a one-way ticket to the “American Dream.”

That dream, facilitated by the federal government — which sent millions to college and prepared millions to enter the workforce, and provided to millions, for the first time, the opportunity to own a home — created the American middle class.

By 1960, with the Veterans Administration having guaranteed about 2.4-million home loans, about 31 percent of the population now lived in the suburbs.

Those bland post-war suburbs — with their prefabricated homes built on tract after tract of land, whose “architectural uniformity was indicted in the 1950s, as a manifestation of an increasing conformity in American society” — have their origin in a Victorian-Era utopian movement, that is also the direct progenitor of a proposed project in New Scotland.

First brought before the town of New Scotland Planning Board in November 2018, the current plan from Prime Companies of Cohoes is to build a 24-lot cluster subdivision on 87.5 acres of land on Krumkill Road.

Initially, the proposal was for 22 lots.

But, as a conventional subdivision, Charles Voss, the planning board’s chairman said at January’s meeting, the project “just didn’t seem right.”

So, the planning board, citing development recommendations made by the town’s recently-adopted comprehensive land-use plan, asked that Prime Companies consider a cluster development, which, according to Voss, made “the development fit the existing conditions of the land...”

Clustering gave the developer two additional lots to build on.

“When you get into a cluster or conservation subdivision, it says in the zoning regulations that the zoning in a sense goes out the window as far as setbacks, lot sizes, per each house,” Jeremy Cramer, New Scotland’s building inspector, said at January’s planning board meeting, “and that is something the planning board would [make a decision] on.”

When it comes to cluster-development applications, the town’s code states that the planning board has the ability to waive zoning requirements for, but not limited to, “lot size, lot width, lot depth, and other various yard requirements.”

A succinct definition from the town’s zoning code says that cluster development “enables and encourages” the “flexible design of land” to promote: the appropriate use of land, control development, and to protect and preserve New Scotland’s natural and scenic — rural — qualities.

In addition, according to town code, lot size in a cluster development is determined on case-by-case basis at the sole discretion of the planning board, with important consideration given to the availability of public sewer and water “in determining the lot size and lot coverage requirements of any cluster subdivision.”

If the project were a conventional development, then each lot would have a required minimum square footage of 22,000. As proposed, lot sizes for 24-lot proposed cluster subdivision vary from about 16,600 square feet to 117,000 square feet; however, due to wetlands on this site, the amount of usable land is limited; six of the lots are less than 22,000 square feet in area.

The lot setbacks in the proposed cluster development are also less than what would be required in a conventional development.

For water and sewer, Prime Companies is proposing to tap a public water supply and to install an onsite community septic system for Krumkill Road.

“It is certainly an offsite expense to bring the water 1,200 feet to our project site and then feed this residence,” said James Easton of JL Development, who was representing Prime at the January planning board meeting. “But that has always been our goal and intention to provide public water. From a sales point of view [Prime Companies] wants to provide public water.”

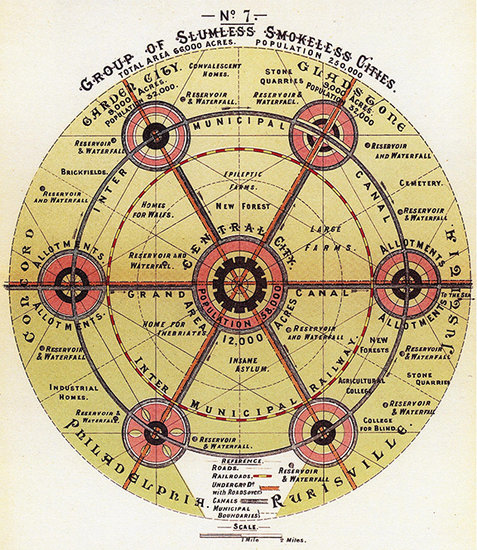

To control urban slums and sprawl, Ebenezer Howard, in 1898, diagramed “garden cities” radiating, like spokes from a wheel, from a central hub, to provide the benefits of town — jobs and entertainment — with the fresh air, beauty, and low rents of country living.

Comprehensive plan

“In creating the community that residents envision,” New Scotland’s comprehensive plan lays out 11 goals to guide the town in that pursuit.

The fourth of the 11 goals seeks to promote active living and improve community health, while reducing the adverse public-health impacts of new development. And one recommendation made to achieve this goal is the adoption of clustering, conservation, or form-based codes to stem developmental sprawl.

Cluster development, according to New Scotland's Comprehensive Plan, “is a technique where homes are clustered on a portion of a site and the rest of the land is preserved as open space. This can be an effective technique for creating a buffer between new development and rural land uses, such as agriculture, but cluster developments are often stand-alone subdivisions in the countryside surrounded by open space and requiring residents to drive long distances to get to daily destinations.

“Learning from this experience, local governments are beginning to direct cluster development to the periphery of existing towns and villages or are limiting their size (e.g., no more than 10 residential lots) to control the impact they have on rural character, agricultural operations, and wildlife habitat.”

New Scotland, the comprehensive plan states, remains by and large a rural community and the Krumkill Road proposal to a certain extent fits with the town’s traditional development pattern “where buildings are clustered in hamlet areas and outer areas remain open…”

There’s a good chance it stays that way: Under a cluster-development model, in order to keep as much of the land on a site pristine, builders are given certain incentives, like being allowed to construct more homes on a smaller area of the site, to keep a portion of the site’s buildable land undeveloped.

Deciding to cluster

The American Planning Association says that cluster development is “a means of accomplishing a number of desirable objectives,” including:

— Preservation of the land’s rural character;

— Cost savings in construction and maintenance;

— Inclusion of special facilities;

— Design variation;

— Privacy and sociability; and

— Lot sizes that are practical and desirable.

To begin, in conventionally-designed development, if a developer owned, say, 50 acres of land with a minimum lot size of 2 acres, then the land could be divided into a maximum of 25 lots, as long as the site has no wetlands or other impediments to construction. The result would be that, with all of the acreage allocated to each of the 25 parcels, there would be little to no land-features protection.

Under the cluster-development model, if the same developer had 50 acres of land with a density of one dwelling per 2 acres, but had some leeway with lot size based on the soil’s suitability for a septic system and a minimum 50-percent open-space requirement, the developer could still build 25 homes; they would just be on smaller parcels of land. And the remaining land could be protected or used for recreation.

Enticing the developer to use the cluster-development model can sometimes mean trading off density — letting more homes be built than the code allows — for open space.

But cluster development comes with its own set of savings.

The compact development means shorter streets and shorter utilities lines, which, according to one account, can reduce infrastructure engineering, construction, and long-term maintenance by 20 to 30 percent.

A cost analysis of eight cluster developments in Illinois found that construction costs on five of the projects had been cut by more than half, and that all projects saw come kind of savings.

“The natural environment also benefits from properly sited and managed open space subdivisions,” according to an open-space handbook from the state of New Hampshire. “Open space subdivisions can protect wildlife habitat and corridors. Quality habitat must meet wildlife needs for shelter, food, water, and reproduction. Ensuring that open spaces in these subdivisions are usable by wildlife, and connected to adjacent open areas, protects wildlife corridors.”

The primary purpose of open-space planning and cluster development, according to New York State, is to conserve, preserve, and protect undeveloped land, and, by extension, the character of a community.

And sometimes the primary goal of clustering is so a development with half-million-dollar homes can get the public water it sorely needs to build an “exclusive golfing and club residential neighborhood.”

Country Club Estates

In April 2006, The Enterprise reported that a literal country-club community had been proposed for New Scotland. “Many people dream of living on a golf course, and that could become a reality for 37 families who can afford $400,000 or more,” the report said.

Amedore Homes had, at the request of the owners of the Colonie Golf and Country Club, proposed to the town’s planning board to build “a 37-house exclusive golfing and club residential neighborhood,” where no lot of land would be smaller than an acre, or 43,560 square feet.

By January 2007, 37 homes had become 42.

And by August of that year, a 35-lot cluster development concept plan was being presented to the New Scotland Planning Board.

“The development has been stagnant for years,” The Enterprise reported, “while a [critical and public] water source was sought,” and eventually found, as the village of Voorheesville agreed to provide municipal water to the site.

The original application had been for 40 lots. However, “We had failed to consider the 17-percent slope … The maximum amount of lots we could fit is 35,” said Daniel Hershberg, who had presented the proposal to the planning board on behalf of Amedore Homes.

A steep slope, depending on the municipality, is generally defined as having a slope of greater than 15 percent; for land with a slope between 15 and 25 percent, only low-density residential development is suitable.

The “per-unit cost” to run utilities up a slope is generally higher than that of flat-land development, and may require additional equipment like a pumping station, which is an added expense.

By December 2008, the planning board had sent to the town board for its review a 40-lot cluster development.

In June 2012, “after years of speculation, delays from a slumping housing market, and a change in ownership, work on the Colonie Country Club Estates neighborhood development, with 40 homes,” was set to begin.

The final plan for Country Club Estates was a 48-acre — 40 acres for development and 8 acres set aside for green space — 40-lot residential cluster development, with two of the lots containing two are two-family homes.

Finally, in August 2014, the first home in the development sold for $526,500.

From England to (New) Scotland

“In many respects,” notes the American Planning Association, “cluster development dates back to one of the earliest town forms.”

As the Gilded Age in America and the Victorian Era in Britain closed the 19th Century, the dawn of the 20th Century saw cities on both continents bursting at their seams, teeming with slums and tenements, a consequence of limited housing.

Amid the chaos, Ebenezer Howard, a court reporter turned land-use visionary, published “Garden Cities of To-morrow,” a treatise deeply influenced by the work of utopian socialists. As London was besieged by thousands people migrating to the city for work, Howard said that, through central planning, small or garden cities — located far from the slums and tenements — could offer residents big-city benefits like job opportunity and a decent wage, while also giving them the benefits that come with living in the country like cheap rent and fresh air.

The ideal garden city sat on approximately 1,000 acres, had a population of 32,000, with a density of about 30 units per 2.5 acres, and was encircled by 5,000 acres of greenspace. And as more cities grew, they would be incorporated into Howard’s “Group of Smokeless, Slumless Cities” which is laid out like a spoked wheel, with a large central city at the hub and smaller garden cities in a radial pattern surrounding the hub, with a vast green space in between.

In the United States, Howard’s idea was co-opted Clarence Stein and Henry Wright, who designed, in Radburn, New Jersey, what is now, “possibly the oldest planned community in the country.”

While across the pond, Howard’s garden cities movement had the high-minded task of combining the best of city and country living; in America, planners had a much simpler task: Stop people from being murdered by cars.

To do so, the “neighborhood unit” was created, “a self-contained neighborhood of about 5,000 residents centered on an elementary school. Bounded by arterial [roads], the neighborhood unit would be bypassed by through traffic and have an internal street system of varied layout,” according to Professor David Ames of the University of Delaware. “Defined this way, the neighborhood unit became a basic design template for laying out residential neighborhoods in North America, Great Britain, and Australia.”

In Bergen County, New Jersey, Stein and Wright began to incorporate the neighborhood unit into their Radburn Development.

Single-family homes and garden apartments were situated on 35- to 50-acre “superblocks,” which had no through traffic and which had homes that were built to face a park, with automobile access provided in the rear of homes. Pedestrians could make their way from superblock to superblock by using tunnels that were built under the roadways.

Radburn had been envisioned as seven separate neighborhoods across 1,300 acres that would house 50,000 residents; however, the project had been built in the throes of the Great Depression, and only about half of the development was ever completed; it’s been described as a “failure in contemporary economic terms.” Radburn did, however, according to the American Planning Association, represent the “first formal introduction of the cluster development concept,” in America.

Summing up the importance of the project, Professor Eugenie Birch of the University of Pennsylvania, in the Journal of the American Planning Association, concluded, “Radburn has had a significant impact on planning theory and vision in the twentieth century … Furthermore, in every generation since the beginning of the movement, planners — always affected by the economic, social, and political environment of their times — have found answers to specific contemporary problems in Radburn.”

Stein and Wright had produced a superior plan, Birch wrote, since their “complex program addressed contemporary needs, primarily the integration of the automobile into residential life.”

The planners who learned their craft at the feet of Stein and Wright came of age during the New Deal, as the federal government pumped untold millions of dollars into the American economy, and, specifically, as it relates to planning, worked on projects related to slum clearance, public-housing construction, and national planning.

And, as the New Deal gave way to postwar America, “the Radburn imprint,” as it related to the “concepts of homogeneity and large-scale development,” had a direct impact on the Federal Housing Administration and postwar suburbanization.

For example, the ease and speed of homebuilding that was a direct result of large-scale homogenous development combined with the G.I. Bill or a mortgage backed by the Federal Housing Administration, meant that a family could buy a home in 1946 for $5,150, and have a monthly payment of about $30 for the next 25 years. The average monthly rent in the United States in 1946 was $35; in New York City it was $50 per month.