Old houses preserve history

An old house can be like an old friend — a comforting presence, sometimes taken for granted.

Old houses can, like old friends, orient us and help define us. We are lucky to live in a place where historic buildings dot our landscape, giving us a sense of history.

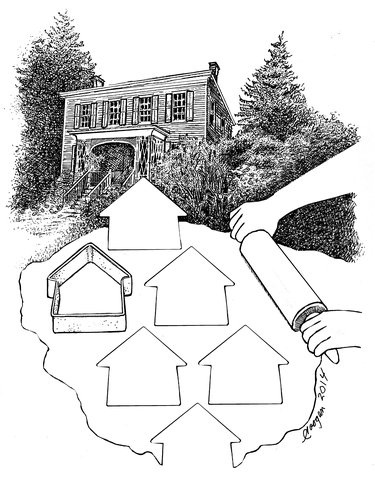

One such building is Rose Hill in Guilderland. When it was built by John P. Veeder in 1842, when John Tyler was president and the United States stretched only as far west as Missouri. Horses and carriages rode a rutted Western Turnpike in front of the large Federal country home.

The house still stands, looking much as it did the year it was built although very little is left of the hamlet that was once Guilderland. A torrent of traffic surges along Route 20 in a largely suburban landscape. Speeding by, motorists can just glimpse a sliver of history at 45 miles per hour.

The current owners of Rose Hill — Dr. Joseph and Lynne Golanka — have lived there and loved the place since 1980. The home’s fourth owners, they have maintained Rose Hill as they found it. Such preservation is a rare gift, and we thank them.

Much has been invested in preserving the nearby Schoolcraft Mansion — using sizeable grants along with some local funds — but no municipality can afford to buy and preserve all the worthwhile historical structures that define our sense of place.

Some tools are at hand, though, if municipalities choose to make use of them. And we urge towns like New Scotland and those in the rural Helderbergs that have not been swallowed by suburban sprawl to preserve what they have before it is too late. Zoning is a familiar tool in this state — New York City adopted the country’s first comprehensive zoning ordinance in 1916.

And a city close to home — Schenectady — was the first in the state to enact a historic-district preservation law; the 1962 law made the Stockade what it is today. Now, more than a half-century later, over 175 municipalities have adopted local historical preservation laws.

A good time for a town or village to address its historic resources is as part of its comprehensive planning process. One of the towns we cover, Knox, in the Helderbergs, is in the process of updating its master plan and we urge town leaders to consider Knox’s rich historic resources as they go through this process.

“Historic resources are clearly part of a community’s physical and visual environment, and therefore the municipal home rule power includes the power to regulate historic resources,” says a paper from New York’s Department of State.

The paper outlines various techniques to preserve historic resources. This includes overlay zones, which can cut across underlying districts, applying a common set of standards; transfer of development rights, where an owner of a designated property may sell his quantitative development rights to the owner of a receiving property; and acquisition easements that allow town boards to acquire fee or easement interests in historic properties by purchase, gift, or other means.

New York’s General Municipal Law is clear on the power of local legislative boards, which, it states, are “empowered to provide by regulations, special conditions and restrictions for the protection, enhancement, perpetuation, and use of places, districts, sites, buildings, structures, works of art, and other objects having a special character or special historical or aesthetic interest or value.”

We urge the elected representatives in our towns and villages to embrace the leadership role they could play in preserving our history.

Individuals, too, can make a difference. Owners of buildings on the national and state registers of historic places — New York has over 70,000 listed — are eligible to apply for tax credits for rehabilitation. Contrary to popular belief, being listed in no way regulates what owners may do with their properties. Private owners of listed properties may alter or even demolish the structures as they please.

Applying to be listed is worthwhile, though, aside from potential tax breaks, because the designation raises local awareness.

Owners of historic buildings can also set an example in how they maintain their property. With rising energy costs, many old-house owners are tempted to get new windows or vinyl siding. This destroys the distinctive fabric of the building without any savings.

The best advice for maintaining old buildings is: Repair rather than replace.

“A historic building is a product of the cultural heritage of its region, the technology of its period, the skill of its builders, and the materials used for its construction,” says the National Park Service in a paper on preservation.

Drafty, leaky wood windows can be repaired and weather-stripped. Good storm windows can be installed over them. The time it would take to recoup the cost of double-glazed replacement windows outlasts a 20-year warranty — never mind the modern look of single large sheets of glass where tiny panes once added charm and preserved authenticity.

On siding, the story is similar. “The character or ‘identity’ of a historic building is established by its form, size, scale and decorative features,” says the National Park Service. “It is also influenced by the choice of materials for the walls — by the dimension, detailing, color, and other surface characteristics.”

The paper goes on at length about the regional differences in how clapboards were shaped and applied.

It also explains that vinyl or aluminum siding can’t fix hidden problems. “It cannot be overemphasized that a cosmetic treatment to hide difficulties such as peeling paint, stains, or other indications of deterioration is not a sound preservation practice,” says the National Park Service. Siding that traps moisture will create an ideal habitat for wood-destroying insects and cause the material underneath to decay.

It also makes the point that, in the long run, siding costs more than regular painting. “To break even on expense, the new siding should last as long as two or three paintings before requiring maintenance,” it says. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, two coats of good quality paint on wood can last to 10 years. To break even with the cost of painting, the aluminum or vinyl siding would have to last 20 years before needed maintenance. It often fades, chips, and dents before that, and is also hazardous in case of fire.

The value of a house and an entire neighborhood can decrease with inappropriate siding. The U.S. Secretary of the Interior writes, “Vinyl siding creates a very different play of light and shadow on the wall surface, thus resulting in a different character. The width of the clapboards is altered, shadow reveals are reduced, and molding or trim is changed or removed in certain areas....Changes to character-defining features of a building such as this always have an impact on more than just that building; they also alter the historic visual relationship between the buildings and the neighborhood.

“Once this siding is placed on a number of buildings, the historical character of the entire district may be seriously damaged. The retention of original materials and their craftsmanship must be of primary importance. When artificial siding conceals the historic fabric, they will always subtract from the integrity of historically and architecturally significant buildings.”

And, as with replacement windows, the much-advertised energy savings just isn’t there.

“The aluminum and vinyl material themselves are not good insulators,” writes the National Park Service, “and the thickness of any insulating backing would, of necessity, be too small to add to the energy efficiency of a historic building....If the historic wood siding were removed in the course of installing the aluminum or vinyl siding (even with an insulating backing), the net result would likely be a loss in overall thermal efficiency for the exterior sheathing.”

The National Park Service’s paper on preservation of historic buildings cites a study in Providence, Rhode Island, which determined that, for a two-story house, 25 feet square, the payback period for 23 storm windows, two storm doors, and six inches of attic insulation (R-20) was 4.4 years while the payback period for aluminum siding with an R-factor of 2.5 was 29.96 years.

The numbers should speak louder than the advertising claims.

For the Golonkas of Rose Hill, replacing the six-over-six paned windows that bathe their home in dappled light was never under consideration. They use 40 storm windows to keep their house cozy in the cold.

“One thing I’m proud of,” Mrs. Golanka said of their home, “it has the original windows...So many historical houses are ruined.”

We need more such caretakers of history. Could you be one?

— Melissa Hale-Spencer