A turn for equity

New York City’s new mayor is fond of referencing the tale of two cities, and promising he will work to end the great disparity between rich and poor. Good for him for having the courage to define the problem and tackle it. It won’t be easy.

His reference, of course, is to Charles Dickens’s Victorian novel, detailing the years leading up to the French Revolution as the peasantry suffered under the heel of the aristocracy and then, in turn, the revolutionaries were brutal to those who had been dethroned. An individual’s virtue, as the French aristocrat Charles Darnay discovers, does not matter once labels are applied. The “long ranks of the new oppressors who have risen on the destruction of the old” prevail.

We need, instead, to let individual worth allow success; class should not define us.

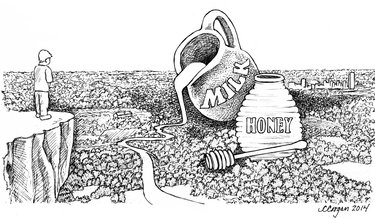

The metaphor from Dickens’s novel applies to more than New York City. All across the state, and, indeed, the nation, the gulf is ever widening between the very rich and the poor as the once-solid middle class is being chipped away and avenues for upward mobility are being blocked.

Here, in the region we cover, which includes both the rural Helderberg Hilltowns and the more affluent suburban towns below the Hill, we are impressed every year with the outpouring of generosity around Christmastime. One shining annual example is the Christmas party, organized by the sheriff’s office, for the Hilltown children.

Residents in wealthier parts of the county recognize the need and make substantial donations. Hilltown parents in need can select from racks and racks of clothing and many tables laden with toys and books and games for their children. It’s positively Dickensian.

But the need is greater than Christmastime generosity can fill. Mind you, we’re in no way criticizing the outpouring of goods and foods that we document on our pages each holiday season.

Contributions cannot reverse the plight of those living in poverty. One of the great attributes of America has been the ease of social mobility. “Poor” is not who you are. It does not or should not define you.

Through readily available public education, America has traditionally offered those who would work for it a chance to better themselves. The stability of our society — and the forward progress for all of us — depends upon that.

That is why we are pleased that, perhaps as early as this month, more Hilltown families will be offered needed social services, as detailed in our front-page story.

The mass of data recently compiled from state-required testing consistently shows that students from wealthy districts do better. Graduation rates released last June by the State Education Department highlighted the ever-widening gap between rich and poor districts. In what the state terms “low need” districts, that is, wealthy districts, nearly 94 percent of students graduate. Yet only 65 percent of students from “high need” districts graduate.

Nearly half the students from our big-city schools don’t have a ticket to society, don’t have a pathway to a better future.

In rural Berne-Knox-Westerlo, we can see the difference family wealth makes in terms of educational success. The 26 “economically disadvantaged” students had a graduation rate of 73 percent while the 71 students who were not economically disadvantaged graduated at a rate of 93 percent.

Children from poor families are no less intelligent than their peers. What weighs them down are the myriad problems caused by poverty.

Quite simply, they need support. These new county-funded programs will help bridge the gap. The programs are described as “preventative”; they will help keep children in their homes, where they should be, with their own parents, by aiding those parents. A social worker will ask the parents, “What do you want to improve your family?”

This is a far, far better approach than taking a child from her parent and placing her in a foster home. Such placement, such rending of family, should be used only as a last resort, for instance, if a parent is abusing a child.

Poverty is a hardship, not an abuse. Loving parents can be taught through this program how to take advantage of community services, such as those offered by churches, public assistance agencies, and food pantries.

Mary Beth Peterson, director of the Hilltown Community Resource Center, run by the Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Albany, put it succinctly and forcefully: “There are no social workers up here; there’s no private practice; there’s nothing.”

Now, there will be something. We urge families who need help to seek it. It is not a handout. The program is paid for with your tax dollars. You are entitled to use it. And you should, for the good of your children and your community.

We’ll all benefit. As more children do better in school and graduate, we’ll start to close the ever-widening gap between rich and poor. We’ll tell the tale of one great society for future generations.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer