Lessons to live by, taught by the dead

One-hundred-twenty-nine years ago, the editor of this paper wrote in this space, “The year of 1884 is fast drawing to a close, and would it not be well to take one glance back over the past year and see if any improvements have been made in regard to our moral, spiritual, or intellectual qualifications, and then start the new year with a better determination....”

He opined about the rapid development of the village after a rail station was built at the foot of the Helderbergs and concluded, during the next year, 1885, “There will be greater improvements in regard to the wealth of our beautiful village.”

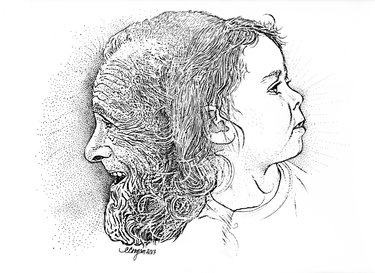

This time of year, there is a tendency to, like the ancient Roman god Janus, look in both directions — back at the year past and ahead to the future. Our pages this week are filled with retrospectives, in words and pictures, of the towns and villages we cover.

While certainly we can note the kind of progress defined in that 19th-Century editorial — more stores and dwellings — it is much harder to see and evaluate our moral, spiritual, or intellectual qualifications.

One place we look in our newspaper for lessons on these qualifications is in our obituaries. We spoke this week to a grieving son, John Fallone, who loved his father, Rocco Fallone, very much.

Rocky Fallone had grown up next to the railroad tracks in Voorheesville during the Great Depression. He left school after eighth grade to help support his family. He volunteered to fight in World War II because he didn’t want to be left out. He survived an attack when a Japanese plane crashed into his destroyer but his wife recalled how he suffered through nightmares for years, remembering his good friends who had died in the attack.

“After he died,” said John Fallone, “I stood next to him and thought, ‘This is the man that taught me what it was to be a man, a real man.’”

Through tears, he described those well-learned lessons: “Be loyal to your wife. Be a strong father. Be persistent through adversity. Be authentic.”

Those values, we thought, are something many of us could learn from.

That led us to look through our stack of newspapers from 2013 in search of the truths told by the grieving about the people they loved. Two obits appeared on our front pages this year.

In January, Edward Breitenbach died at the age of 85. He was a builder, not just of structures but of community. A tough city kid from Queens, he worked his way through school to be an architect. He designed a home that his family helped build on 78 acres sprawled on the hill above Altamont.

In his basement office there, he designed buildings that define the local landscape, from Altamont’s bank and parish center to the Guilderland Center nursing home — one of dozens he designed throughout the Northeast, initiating the trend of numerous wings projecting from a central nurses’ station.

Breitenbach was a founding member and first president of the Guilderland Chamber of Commerce as well as being active in church and civic groups.

So, an architect can leave behind buildings, bricks and mortar, that stand as a testament to his work. But this one also left behind a model of how to embrace life — wholeheartedly.

His son, Thomas Breitenbach, said, “I wish I was like him...so extroverted, so personable.” He was outgoing, his son said, “till the day he died.”

“The nurses told us how, despite the pain, he would give a smile and say, ‘Good morning, Beautiful.’”

We had another front-page obituary, in June, after Lieutenant Colonel Todd Clark, who was raised in Guilderland, was killed in Afghanistan. Schoolchildren lined the road as the black hearse with the United States Army seal on its door rolled under an American flag suspended between the ladders of two fire trucks; the flag’s red and white stripes were reflected on the shiny surface of the hearse.

A career Army leader and a married father of two, Clark was 44 when he was killed as he trained Afghan soldiers.

Kids often see reality clearly without the layers of culture that can cloud or color a grown-up’s view.

“He was the only man I knew who was as strong as he looked,” said Kay-Leigh Hicks, a young cousin of Clark.

Another cousin, Sierra Pizzola, described him as a “glass-half-full kind of person.”

“How quick he was to shine a light on others,” not craving attention for himself, the priest at his funeral said; Clark exemplified “that camaraderie” that exists between brothers and sisters of arms.”

From the way Clark lived and died we can learn the worth of real strength when it is used to protect and serve others.

The priest at Clark’s funeral concluded, “Our life with Todd is not all in the past...He is cheering us on...to live life with dedication, with honor, with valor and humor, but most of all with love.”

Mary Etta Klatt, who died this past August in Knox at the age of 98, labored in her youth on a farm where her family pumped water by hand because they had no electricity and used an outhouse through 30-below Minnesota winters.

Later, she raised her own family on a dairy farm. “Mom may have been worried on the inside, but she just coped,” said her daughter. “She figured out how to get by, how to do it.”

A sense of fearlessness and willingness to try new things was a family quality.

If she could not afford clothing for her kids, she’d pull apart a dress of her own and remake it into clothing for them.

How many of us do that — figuratively, if not literally? Would we take something of our own, maybe not the clothes off our back, but something we value, and reshape it, work at it, to give it to someone in a new form, someone who needs it?

We could, and we should.

Mary Keefe Lawrence grew up among 13 siblings with a life of hardship, too. She died in Voorheesville in September at the age of 92. She didn’t have a home of her own or a bed of her own, sharing with several siblings.

Her father, a musician, died when she was just 4 years old. Her family was artistic and, although poor, most of the children could play instruments by ear. She stopped going to school in the 10th grade to help support the family.

The man she married had lost his home in the Great Depression, their daughter said. “My mother never had one,” she said, “but, they were bound and determined to make it happen for them, to make something they owned, that they weren’t in debt. And they weren’t afraid to roll up their sleeves and mix some concrete.”

Lawrence would tell her two daughters, “A woman can do anything a man can do, and she can have a baby.”

We learned from her the lesson of perseverance, making a dream quite literally concrete through hard work.

We have posted on our office wall a copy of a picture that Lawrence drew while she dealt with Alzheimer’s disease as an elderly woman. Her drawings were fanciful and colorful. The detail we have posted comes from a picture of a woman walking a cat with a jeweled collar.

The cat has an almost human face. And it is smiling.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer