Mr. Schneiderman, indicting Father Young's work would miss the mark

Hope is the thing with feathers — That perches in the soul — And sings the tune without the words — And never stops — at all....

— Emily Dickinson

Father Peter Young spawned a movement. He changed the way lawmakers and the public look at alcoholics and drug addicts.

With this perception came help, real help, to set people on the course to productive lives.

We have written about Young many, many times over the decades. A Catholic priest, he is the chief executive officer of Peter Young Housing, Industries and Treatment, a $20 million organization that had 90 residential sites in the state, in-patient treatment centers, half-way houses, and contracts with various agencies and companies to hire the people he is training.

Until last month, he had, for 35 years, run programs out of the former seminary on the hill above Altamont. We were saddened to report last week that his drug rehabilitation program there has closed.

At the same time, we were heartened to discover that Dr. John Malfetano is setting up a practice in the building and wants to attract others to make it into a medical center. It would be a service to Altamont and the Hilltowns to have a medical facility close at hand.

The work of Father Young, though, is not likely to be replicated. And — although Young told our reporter Anne Hayden Harwood that the Altamont center was closing because of regulations that prohibited other programs, which helped pay expenses, to co-exist with a drug rehab program — he faces a far larger problem.

The state’s attorney general has called for a grand jury to assemble to consider the alleged misappropriation of grants by Young’s organization.

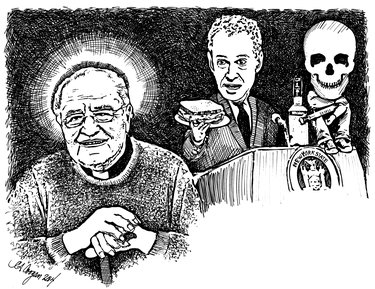

In 1985, Sol Wachler, then New York’s top judge, proposed that the state scrap the grand jury system of bringing indictments. He famously told Marcia Kramer of the New York Daily News that district attorneys have so much influence on grand juries that “by and large” they could get grand juries to “indict a ham sandwich.” Tom Wolfe popularized the phrase, now heard on TV crime dramas, in his 1987 novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Father Young may well be as suspect as a ham sandwich; we believe assembling a grand jury is a mistake. If there is an indictment, funds for Young’s good works will be further cut off, leaving many who most need help no way to get it.

“He is not the person they are looking at, but he is the whole organization,” said his lawyer, E. Stewart Jones. “He has spent his entire life and all of his money on this.” The attorney general’s office would not comment on the case.

Jones said the charges stem from “a paperwork mistake.” Two grants were awarded to Young’s organization, each meant for a specific purpose, Jones said, and, as a result of the paperwork mix-up, the grants were switched.

“No one has benefited from it,” said Jones. “It was not something that was done intentionally.”

Young said that block grants, awarded to help residents of specific counties or communities, were inadvertently used on people not originating from those places. “We took in people whose cases were pending,” he said. “We just took whoever came in to any of our facilities.”

The mistake was discovered when Young’s organization self-reported an internal theft, which led to a broader investigation, Jones said.

Certainly, if funds have been misappropriated, they should be paid back, and a system should be put into place that will assure funding goes to the proper places.

But, if that is the crux of the allegations, we join with Jones to urge the attorney general to disband the grand jury.

“You are talking to a devastated man,” Young, now in his eighties, told us last week. This is a man whose motto in treating people addicted to drugs and alcohol has been: “We’ve got to give people hope.”

Through years of listening to those in need, Young distilled his mission to a crystal clear mantra: “Find programs applicable to their recovery.”

When Young began working in Albany’s South End in the 1950s, alcoholism was a crime. Martha Holesapple was arrested for public drunkenness 238 times, Young once told us. That’s what spurred him to action.

Stigma, said Young, is the similarity between the addicts that he helped in the 1950s and ’60s and the sex offenders he started helping at the beginning of this century. “The biggest thing I did was de-stigmatize,” he said. “I de-stigmatized addiction.”

That’s what enabled people to get help; when they no longer had to admit to being a criminal to attend Alcoholics Anonymous, people began to get help, he said. After years of work, Young won support for decriminalizing alcoholism and, since 1976, a person cannot be jailed for public intoxication, he said.

At first, he said, politicians saw his priest’s collar and dismissed him as a do-gooder, but, when he presented the costs of incarcerating drunks, he got some attention and support.

“I proved it was cost effective,” he said. “That’s how I got credibility.”

Most recently, at his Altamont center, Young had a program for military veterans of the Gulf Wars who, in addition to physical injuries, had to grapple with mental injuries, too.

In 2009, we profiled a graduate of one of Young’s programs — the Honor Court program he set up in 1983. Brian Hussey had spent 20 of his 25 years addicted to drugs — both of his parents were heroin addicts, he said.

Before sinking further — to prison, serious criminal behavior, or homelessness — Hussey, up on drunk driving charges, got caught in the web of help that Young had spun for over half a century. He spent four months learning a trade in one of Young’s programs.

On graduation day, Hussey said his overall goal was “anything I can give back to Father Young. He got me clean after 20 years of use and now I have a future.”

One young life back on track is emblematic of Young’s approach. A study done by the State University of New York School of Criminal Justice in 1997 found that people who went through the Father Young programs returned to prison or violated their paroles only 8 percent of the time, as opposed to 80 percent for those who did not participate.

The United States has more prisoners than any other country in the world. Programs like Young’s help reduce those numbers. His resounding call has been to create taxpayers. We take this to mean functioning members of society, citizens who contribute.

The hope offered by Young’s program has saved taxpayers countless dollars in reduced prison costs, but, more importantly, saved human lives from misery. That hope should not be extinguished because of a paperwork mistake.

Young says his moral guide in life is the Beatitudes, in which Jesus names eight unfortunate groups, and says how each is blessed, as in, “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the Earth” or “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

In his lifetime, Young has taken groups that are reviled and found ways to bless them. First, with alcoholics, he raised the public’s consciousness so they could be understood not as criminals to be punished but, rather, as those suffering from an illness who needed help.

He went on to do the same with a more reviled group, drug addicts, and then was working with the most reviled group, sex offenders. Young was in the business of giving people hope.

Just as the law missed something important when it jailed Martha Holesapple 238 times — jailing her wasn’t solving her problem or anyone else’s — it would be missing the mark by seating a grand jury in this case.

“It’s a struggle between following the Beatitudes and following state regulations,” Young told us.

There must be a way to help him do both.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer