After Judas Iscariot, Jesus’s other apostle Thomas — known as Didymus, the twin — was arguably the most despicable of the very first Christians. Judas sold out Jesus for money — for 30 pieces of silver, the gospel writer Matthew says, while Luke and John say he was possessed by Satan, that is, had gone off his rocker.

The case against Thomas was based on his denial of the most fundamental belief of Christianity — the raison d’être for Jesus being born — that he, though having experienced human death, rose from the dead and thereby beat death at its own game.

With Thomas’s denial we get the archetypal character of the “doubting Thomas,” an epithet applied to someone who rejects belief in some basic principle or event. The disbeliever is chided, “Ah, don’t be such a doubting Thomas.”

The gospel writer John says that, after the Good Friday execution on Golgotha, the official Registrar of Deaths had Jesus listed in the dead column but that he soon appeared, as if alive, to all the apostles, except Thomas was out at the time.

When he got home the 11 others excitedly exclaimed, “We have seen the Lord! He was here! He showed in person! He’s alive!” Thomas thought they were off their collective rocker: Jesus was dead; everybody saw him die on the cross.

But Thomas conceded he would believe if he could stick his finger in the holes in Jesus’s hands from when they nailed him to the cross, and could stick a hand in the hole in his side where a soldier had pierced him with a spear.

The story continues: Eight days later, all 12 apostles — Matthias had replaced Judas — were gathered in a locked room and Jesus appeared again, this time passing through the door as if he was Casper the Ghost.

He wished everyone peace, “Pax vobis,” then turned to Thomas right away — it was a business trip — and said, “Thomas, take your finger and stick it in these holes in my hands and put your hand in my side where the spear went, and stop being a disbeliever: Believe!”

All a stunned Thomas could say was, “My Lord, my God.” The vulgate says: “Dominus meus et Deus meus.”

Looking at him Jesus said, “You believe because you see what’s in front of your eyes, but blessed are those who do not see such things, physically, and believe.”

The moral of the story? The true Christian believes that Jesus rose from the dead — bodily — and that that body, as some gospel texts proclaim, later ascended into heaven to sit at the right hand of God.

What resurrected these thoughts in me was an article in The New York Times this past Easter (April 9, 2023) by an Anglican priest, Tish Harrison Warren, called “Did Jesus Really Rise From the Dead?” She meant bodily.

Not to be disrespectful but the “bodily” part reminds me of when my chums and I played “Cops and Robbers” as kids and someone got shot dead; after a few minutes the dead person got up, came running back in the game shouting, “New Man! New Man!” And we accepted it.

Warren’s article turned out to be an interview she did with the renowned scripture scholar N. T. (Tom) Wright whose 848-page scholarly treatise “The Resurrection of the Son of God” appeared in March 2003.

Wright, once the respected Bishop of Dunham in the Anglican Church — the same denomination as Warren — also held the esteemed Chair of New Testament and Early Christianity at St. Mary’s College in the School of Divinity at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

He was long interested in a Christian’s view of life after death and, with respect to whether Jesus rose from the dead bodily, he said all the biblical talk about resurrection and apparitions, etc. was not metaphorical. The guy came back.

Wright’s thinking is considered by many as theologically and Christologically conservative; in 2005, he threatened to discipline clerics in his Anglican Church who registered or blessed a civil partnership. He was incensed that an openly gay Anglican vicar had exchanged vows with another man inside a Newcastle church.

On March 11 of the same year — two years after his magnum opus appeared — the bishop found himself on a stage in the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary with John Dominic Crossan, an Irish-born, former Roman Catholic priest, prepared to debate/discuss/dialogue — but not argue — with the man about the correct view of the life and death and after-life of Jesus. The session was advertised as “The Resurrection: Historical Event or Theological Explanation.” It was standing-room only.

To those committed to getting to the bottom of this pons asinorum, the session was their “Rumble in the Jungle” or “Thrilla in Manila.”

Everything the two said, and discussed, and exchanged views on that day, can be found in “The Resurrection of Jesus: John Dominic Crossan and N. T. Wright in Dialogue,” which Fortress Press put out a year later; its editor, Robert B. Stewart, included articles from eight renowned scholars to help make sense of the issues.

I might add that Crossan was and remains the world champion of scholars on Jesus’s life, death, resurrection, and ascension. He’s got more than 15 books on the subject without an ax to grind.

What he shared in his discussion with Wright was what he’d said many times before. In his 1998 “The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus,” he said, “Bodily resurrection has nothing to do with a resuscitated body coming out of its tomb … Bodily resurrection means that the embodied life and death of the historical Jesus continues to be experienced, by believers, as powerfully efficacious and salvifically present in the world. That life continued, as it always had, to form communities of like lives.” As in communities of love.

In other words, Jesus died, and was no more, and would never be again. And for all the talk of Mary Magdalene finding an empty tomb on Easter morning, the stark reality is that a renegade peasant Jew like Jesus, crucified on a cross for being a rabid insurrectionist, was not likely to see a burial at all.

As Martin Hengel says in “Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross”: “The crucified victim served as food for wild beasts and birds of prey. In this way his humiliation was made complete. What it meant for a man in antiquity to be refused burial, and the dishonor which went with it, can hardly be appreciated by modern man.” Id est, Jesus was chum.

When I was in fourth grade in a Roman Catholic school being taught a lesson on the mother of Jesus rising from the dead and being assumed into heaven, bodily — the same “perk” as her kid — I told the nun that that was preposterous; I said Mary, like everyone else, was buried below forever and ever.

I wrote about it in a monograph in 2010 “El Día Que Me Hice Un Poeta” (“The Day I Became a Poet). After I registered my objection — I was 10 — as I say in the text, “The nun responded as quickly as I had to her: Impossible, [she said], that is blasphemy; the things of God are not the things of this world. The body of the mother of the son of God lives in heaven forever and ever without stain of sin or death.”

Two things I am sure of: the first is that the day I became a poet, life and death were one; the second is that, if John Dominic Crossan were a web designer today, he’d offer his services to any loving couple who wanted to marry, doing for them what Jesus had done for him.

A very much belated Happy Easter.

For James O’Donnell

Not too long ago, in the midst of a conversation I had with a woman at our local coffee shop, the lady asked, “What do you do?” As in: what kind of work?

I said, “I'm a poet.”

She said, “Wow, a poet. I never met a poet before. I know poets write poems but how does such a thing happen?”

I said, as a poet, “I spend my days sitting by the well of silence waiting for words to be born; I’m a handmaiden, a midwife. I receive newborns into the world before the State, Religion, and the Marketplace get at them and start twisting meaning for their own purposes. So you see, as a poet, I can have no horse in the race.”

The lady continued listening then came forth with a “Double wow.” Pausing for a second, she said, “Well of silence? What is a well-of-silence? And where might such a thing be?”

I said wow back to her, letting her know I would answer her questions another time, that they were heavy questions requiring heavy answers.

“For now all I’ll say,” I told her, “it’s a pleasing vocation, being a poet. There’s not a lot of money involved but the well offers an equanimity no ideology or cost-effectiveness scheme can equal.”

I was waiting to hear a third wow but all I got, oddly enough, was silence; she stood there musing before me. I remember thinking, “This lady might be for real; she really wants to understand how a word is made flesh.”

And I will add that, if one is called to listen to words being born for a living — before the horse-racers get at them — that that work requires a special kind of ears, a special listening skill or competency — and all I mean by “special” is that it involves hearing ordinary and extraordinary speech simultaneously.

You can understand how someone might get stuck at “well-of-silence;” the thought bedazzled my acquaintance at the coffee shop.

Some writers — as real readers know — keep notebooks that contain drawings, profiles of places and persons met, short poems, and the like, every form of which speaks to what takes place at — and the effects of — the well of silence. It’s the reflective part of a poet’s life.

And the content of such notebooks — even of famous writers — ranges from (seemingly) scribbled notes to deeply profound thoughts. The late great American poet Allen Ginsberg used to put thoughts down in prose and from those sculpt a poem.

And even though at times the words that emerge from the well of silence appear indecipherable — they’ve just been born! — I disagree with the British writer Lawrence Norfolk who thinks such thoughts constitute a “junkyard of the mind.”

He says notebooks are no more than a bin, “of failed attempts” conceived in “widely-spaced times and places,” reflecting “diverse scrawls of varying levels of calligraphic awkwardness,” due to a “lack of firm writing-surfaces [and] different modes of transportation.”

Such a statement — for all its purple prose — raises a million questions. The first is: Norfolk says a notebook is a repository of failed attempts — as if a poet or writer had volition over what he was called to listen to.

Some writers refer to their failed attempts as “false starts.” For example, a novelist might say: “I started writing about a detective from the homicide division in a small midwestern town only to find out no murder occurred so there was no need for the cop.” A start like that goes into the trash.

The writer, Jon Gingerich, said he wanted to save writers from all “Dead Ends and Bad Beginnings.” Indeed, he offered the reader a “Guide to Successful Storytelling Patterns.”

So many people seem unaware that we all engage in storytelling patterns every day of our lives, that it’s au naturel, part of human DNA. Gingerich just wanted to save people from wasting time, from spilling the ink of life onanistically, and succumbing to a cycle of defeat and loss.

When a woman is in labor, she does not think she’s wasting time waiting for the baby to come. She’s all Zen, life lived a second at a time: no horse no race no false start. Biologically, she is the well of silence.

The late great socio-political journalist ethnographer Janet Malcolm — she really was a mystery writer — had a book appear a few years before she died called “Forty-one False Starts: Essays on Artists and Writers” (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2013). As a teacher of writers, she explains her use of “false starts” though there never was a hint of falsity in her.

Of course I believe there is no such thing as a false start: I write what the Muse tells me to and when she tells me; poetically she is the well of silence; she says everything I need to hear and when I need to hear it.

For years I taught a course at our public library called “Writing Personal History for Family, Friends, and Posterity.” From the very start, all the “students” were chaffing at the bit to tell how the well of silence had affected them. Through the library’s Friends group, they put out a book of their stories which is a wonderful guide to successful storytelling patterns. It is called “Tangled Roots.”

For those wondering what an entry in one of my notebooks looks like, I offer the following written on May 10, 2023; at 6:51 pm; in Voorheesville, New York.

The note reads:

She said to him: I can only go at a certain pace. He said: You’re much too slow. She said: I’m dying, won’t you take me along?

He said: Lady, we all got problems; the river of life moves at a pace all its own.

And I, sitting between the two, says to the gent: This is your love speaking who’s on her way out, and all you offer is: Achtung!

Achtung? Imagine saying to a rose on the first day of May: Achtung! A rose; the first day of May; Achtung; a defilement of planetary consciousness.

The guy said those things; I was there, I heard Achtung.

And the aforementioned slow-poke friend of mine did die and left behind a raft of unexplored selves.

I can say more of her last days on earth but I am just a poet — look at my bank account — a transparent eyeball selling nothing short because I sell nothing at all.

Except for a few Julius Caesar books these days and for that I offer a mea culpa.

Spread out across the top of an old glassed-in bookcase in our living room is a creche — a nativity scene — that depicts the birth of Jesus: Mary, Joseph, Wise Men, shepherd, animals, all those chosen to witness what Christian theology came to call the Incarnation, are there.

We keep our set up all year round; the silence is arresting.

Creche comes from the Old French crèche meaning feeding trough or manger, the basis of the much-loved Christmas carol, “Away in a Manger.”

(And, editorially speaking, with respect to Christmas carols, Nicholas Parker, at the New York Public Library, said, “Christmas songs in the pop or jazz music canon, such as “Let It Snow,” “Last Christmas,” “Jingle Bell Rock,” “White Christmas,” etc., don’t count as Christmas carols! A carol has to be traditional or biblical in nature.” QED.)

As a kid, I was taken with the word manger — I have no idea why — the Greek is φάτνη — the Christmas committee in some churches pack their manger with straw to make things look real.

The Methodist Church in our community used to have a “living creche” they set up along the main road; in the cold of December, parishioners gathered round the child to relive the first Christmas. A teacher from the high school brought a lamb for nuance.

I still admire those who gave up their evenings that way but I wonder if any passersby got something from it: Did it affect their view of Christmas, or Jesus, or what it means to be part of a Christ-like community?

Since nobody at Jesus’s birth wrote about what they saw, their story died with them — the gospel writers never met them and no oral tradition passed it on.

Thus, it was up to painters, poets, writers, and makers of ceramic statues to say how people looked, how many there were, where they stood in relation to the child, and the expression on each face as if in a photograph.

In terms of accuracy: The gospel writers provided the outline, the artists ran with the ball.

The characters in our creche are sizeable: The wise men measure 10 inches tall and have full bodies; the same for Joseph. There is no stable or covering so our scene is al aire libre.

Center stage is the child Jesus stretched out in a manger, looking upward. The gospel writer Luke says — the only evangelist other than Matthew to write about the event — “And she [Mary] brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger.”

They said it took place in a stable — later they said a cave — because the family had no money, but the truth is the little town of Bethlehem was flooded with out-of-towners reporting for a census — every room everywhere was full. So the family could have had money.

Older people remember, “there was no room for them in the inn” but the New International translation says, “because there was no guest room available for them.”

And swaddling clothes? Old creche scenes show the boy wrapped round and round in a bundle of wide ribbon; biblical scholars went back to the Greek and came up with “cloths.”

Thus Luke 2:7 now reads, “She wrapped him in cloths and placed him in a manger, because there was no guest room available for them.” “Cloths” and “guest room” are new; “manger” remains.

(Paradoxically) the scholars were hoping the text could provide context.

In our creche, Mary is kneeling next to the child — the colors of her robes are a Rorschach test.

For a long time, I thought Joseph got the short end of the stick — though I think he saw deeper into who the child was than the mother: though they both knew they had a gifted and talented kid on their hands, with intimations of divinity.

I’m not saying Mary was on the outs, just that Joseph and the boy spent time together in the wood shop and, as woodworking artists know, the silence of wood runs deep.

Some scripturalists treat Joseph like he was a piece of wood, instead of a man trying to solve a problem. That is, Matthew says, “Mary was pledged to be married to Joseph, but before they came together, she was found to be pregnant through the Holy Spirit.”

As in: Mary says to her boyfriend, “Joe, I’d like to get married but there’s something you ought to know first.”

And Joseph, because he was, as the Bible says, “faithful to the law, and did not want to expose her to public disgrace, he had in mind to divorce her quietly.”

What! It’s not even Christmas Eve and Jesus’s parents are getting divorced!

I have inches-thick commentaries explaining what the gospel writers meant by virgin birth — virgin as in sex with a spirit doesn’t count.

A modern-day version would have Joseph staring down every guy who came near the house and checking Mary’s cellphone when she went into the shower.

Our set has one shepherd, who’s as tall and wide as the wise men. Draped over his left arm is a lamb in easy repose.

Animal-wise, our set includes a camel, a donkey, and the lamb: the lamb a projection of the lamb of God Christians sing about in their liturgy: “lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world,” then they say “have mercy on us,” which means they believe the lamb is a god.

At night, a stressed-out Joseph dreams of an angel who tells him not to worry but “to take Mary home as your wife, because what is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit”

Again, as if a Holy Spirit “intervening” your wife should get a religious discount.

The angel tells Joseph that Mary “will give birth to a son, and you shall call his name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins.”

There’s a doctoral dissertation in the creche thing: an analysis of the facial expressions of each of the characters in a Christmas creche. The research design could include examining the top 1,000 creches ever made — however determined, however randomly selected — to see how many witnesses the purveyors project were there, what their faces looked like — how elicitive of truth — was the family poor?

I wish all the souls in our creche could speak so I might interview them like a Rolling Stone reporter at the first Woodstock, dated 0 B.C./0 A.D.

Luke says, “There were shepherds living out in the fields nearby, keeping watch over their flocks at night.”

Which we expect of shepherds, but then it gets weird: “An angel of the Lord [appears] to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified.”

They must have thought it was an invasion from Mars.

The angel tells them not to worry but to go to Bethlehem and find a new-born “wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger,” then the light show begins because it says: “a great company of the heavenly host appeared with the angel, praising God and saying, ‘Glory to God in the highest heaven and on earth peace to every living soul.’”

The shepherds must have thought they were seeing The Mormon Tabernacle Choir dosed on acid.

And yet they “go to Bethlehem and see this thing that has happened,” and find, “Mary and Joseph, and the baby, who was lying in the manger.”

Then they lose it altogether, the gospel says, “When they [the shepherds] had seen him . . . [the child Jesus] they [went out] and spread the word concerning what had been told them about this child, and all who heard it were amazed at what the shepherds said to them.”

Spread the word? What word! Everybody amazed? At what! What did the shepherds say? And who was taking care of their sheep!

(The shepherds were the first apostles.)

This is the best Christmas I ever had. How about you? Does your creche have a manger?

For Walt Chura of Simple Gifts

In the summer of 1954, the great innovative psychotherapist Carl Rogers presented a paper at a mental-health conference in Toronto, Ontario called “Personality Changes in Psychotherapy.”

He wanted to share with the conferees the results of a four-year study he conducted that asked the question: What is therapy?

One would think that everybody at a mental-health conference would know what that was (especially Rogers) but the conferees wanted to hear what the cordial mystic guru — to some a miracle-worker — had to say about how better to help people heal. His words were always instructive.

Of course, Rogers’s research team was interested in what takes place during the therapeutic session, how the “talking cure” affects a person’s cognitive development: remembering, understanding, analyzing, and all the other dimensions of human consciousness.

They were trying to nail down the click that takes place in a person’s mind when a door opens and the aspirant moves from point a to point b, then from b to c and so on, and at each stage becomes a more mature (realized) adult; many dedicatees experience past, present, and future melding into one — further relieving anxiety. (No small feat even for a pro.)

People who experience success in therapy are happy to share stories of their new-found-freedom: They say they feel better; get along better with others — even somebody they meet on the street; they say they see things clearly — read situations better — and thus find themselves in fewer hissy-fit-hassle-ridden conflict situations, even when the other person is at fault. They say they feel closer to achieving their dreams: Nirvana might be just around the corner? That’s not an LOL.

In Toronto, Rogers referred to the patient who makes great strides in therapy — who is better able to relate to others as an adult — as a “well-adjusted person.” It’s not a phrase we hear in the United States anymore because the country no longer has shared, agreed-upon values to adjust to, there are no ideals that say how one American should relate to another for a “common good.”

Much has been written about how the United States did have a collective sense of herself after World War II, when some/most people thought everybody was in the same boat or, if there were different boats, the big boats weren’t sticking an oar into the little boats’ eyes.

That sense has dissipated, deteriorated to the point where the country is rudderless, afloat like an anchorless ship — a serious mental disability a lot of people still refuse to admit exists. They have distanced themselves so far from feelings associated with a harmonious community that nothing anybody else does matters to them; they’re nihilists. The country is flooded with nihilists.

Of course, as soon as anyone hears the words “well-adjusted,” they ask: Adjusted to what? Which is the right question, and an especially poignant one for America right now because there is no United-States-of-America; “America” has no home; is homeless — I just said an anchorless ship — we’ve lost the competency to relate to each other in a cordial neighborly way, which the framers of the Republic, with all their flaws, were hoping that was the least Americans could do.

And relating to others in a cordial neighborly way is in fact a competency — techniques and frame of mind — that people must learn, and practice, and get good at it, if they are to have a society where, for example, everybody has enjoyable work to do, where people feel part of a nurturing family, a culturally-enriching school district, and friendly local “fraternal” organizations like the Rotary Club and the Bicycle Days Committee.

The idealists say everybody should get two months of vacation each year, fully paid, all the sick leave they need, and a sabbatical every 10 years: a whole year to think and read and study and ponder and do the things their soul is longing for — paid in full — untaxed — no one having to worry about a guy at the mall whipping out an Uzi to mow the food court down.

(I’m thinking of putting out a pamphlet called “Ways to Have a Healing Vacation.”)

Thus, if a sincere person wishes to be a well-adjusted American, what America is he going to commit himself to? America is a mirage of shifting identities. It’s like someone looking in the mirrors of a barber shop to see what they really look like.

When a lieutenant in the Proud Boys hears “well-adjusted,” he thinks of the recruit who spews venom at the system, preys on human weakness, keeps ammo hidden in the car — long guns aside — and a bunker to hide in when the cops come; he does everything the Proud Boys Handbook requires, uses violence to settle scores, interjects suspicion in every group he comes upon. Looking at such a recruit, a Proud Boys lieutenant will say: I say, that boy is one “well-adjusted Proud Boy!”

Using “well-adjusted” alone, therefore, shows why Rogers said “well-adjusted person,” person being the operative word, as in: What’s the difference between a well-adjusted Proud Boy and a well-adjusted person? And a “person” is not an “individual,” a unit among “units” for utility’s sake — paying social services and the police to clean up deviant detritus.

After many years of observing and helping people grow into adulthood, Rogers put together a book called “On Becoming a Person” in which he touches upon every aspect of therapy right down to the words people use when they experience a seismic shift in their personality — as it’s happening — patients the true definers of what therapy is.

Also, while people refer to themselves as Socialist, Democrat, Republican, Libertarian, Anarchist — whatever — there is a group whose members call themselves Personalists, always making clear that Personalism is not a political stance but a way of life that has implications for politics. One personalist I know says he votes 365 days a year with his body — the kind of devotion some say a healthy Republic needs to stay alive.

When people entered Rogers’s study, they were handed a list of the qualities of a very mature person and asked to pick which ones most reflected them, and then to put in another pile the qualities that were not like them — it was a base from which the team would work.

Then each subject was asked whether the self they were right then, squared with the person they thought they ought to be, or wanted to be, or felt called to be, their “ideal self,” the self they had to bank their life on.

Looking at how people scored themselves on these dimensions, Rogers and his team saw right away that troubled people experience a wide gap between the self they see themselves as and the self they feel they ought to be, maybe the self they were born with. It’s a tricky subject to document because people don’t like talking about “self” stuff.

Which explains why America is a hodge-podge of once-lofty ideals riled up by grunts battering America in the face. Imagine: Some folks are still calling for civil war — ready to hack down a neighbor like they did by machete in Rwanda in 1994, a homeland where no one felt at home.

I love the song “America the Beautiful” but now I hear “America the Confused,” “America the Angry,” “American Despair” identities that swish back and forth like dirty tide water.

At this stage of my life, I find all this so sad. I have no god but, if I had one, she’d be the goddess of understanding and compassion, the genealogical mother of love.

Being a grandparent, I sometimes wonder what other grandparents say to their grandkids.

Some grandparents are unable to speak to their grandchildren once they reach high school age. They’re like two acquaintances forced to be together with nothing to say.

I believe, like Shakespeare, that human life is lived on a stage that every person stands on whether they wish to or not, whether they acknowledge the fact or not.

And for those who frump it and say they have nothing to say, well, by doing so, they’re having their say: to the puzzlement of family and friends.

On the stage, as we read the script assigned us — some say they create the script themselves — we attest to our value in life, our worth in relation to others, and our place in the history of human existence, all with grave consequences for our subconscious.

Macbeth speaks for Shakespeare speaking about life as a minimalist:

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more.

I would love to sit down with Billy S. and ask him what that means and how such thinking affected his writing.

With respect to the stage conceit, I’ve often said that, when I was young, my parents were in the first row, in the footlights, directly facing the audience. Then, when they died, without me doing anything, I was whisked to the front where they once stood and it was me in the footlights facing the audience, directly, eye to eye, the footlights revealing the intensity of the relationship.

I was there for a while but then, when my son and his wife had a child, I was whisked to the back of the stage and my son moved to the front, at the footlights, the grandkids behind him, in front of me. I’m farthest back from contact with the public.

All these shifts in generational positioning have had me asking questions about who my grandchildren are, and not just mine but grandchildren en générale — the intergenerational thing.

My grandkids are related to me but they live in a whole other universe in that, when my son was growing up, he was in the house here — we had a face-to-face relationship; I had some control over him and to a large extent the conversations we needed to have.

I have three grandchildren and continue to wonder who they are, and how I might introduce myself without pushing them away — but remaining true to myself — in no way wanting a pal.

I used to say I wanted a grandfather like me but I also know some kids are born into the wrong family, which means they have the wrong grandparents: I might be no more my grandchildren’s cup of tea than the guy selling hot dogs at the food cart in front of the New York City Public Library on 42nd Street.

On one level, it doesn’t matter; on another, well, the story is worth its weight in gold, that is, how grandkids assess their grandparents in private, and whether later on they have a sense they came from them.

The passage of traits from generation to generation needs more study, especially from grandparent to grandchild.

Because I’m a poet, I have written a birthday poem for each of the three grandkids — not an occasional poem — for nearly every year of their lives. They’re in my published books.

The oldest grandchild just turned 19, the last day of August, the week after he left for school in Maine. I have many poems for him.

What follows is a short prose poem I’m sending him as soon as I’m done here. When he reads it, I hope he doesn’t say he’s in the wrong family.

Maybe you speak to your grandkids the way I do — I have no idea. Regardless, I pass on the following text in case you are one of those grandparents who sometimes wonders how other grandparents speak to their grandkids.

THERE ARE MANY WAYS TO SAY BUEN VIAJE

For C. M. A. SULLIVAN

A guy I once knew used to say: If you knew me like I know me, you’d … and then he’d stop like he just got caught doing something bad.

It was noticeable. I saw it because years before I began to fly above the world and see as Selma Lagerlöf’s Nils Holgersson does in “The Wonderful Adventures of Nils.”

The Polish poet, Czeslaw Milosz, spoke of such sight in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1980. (Lagerlöf got the prize in 1909, the first woman to do so.)

It seems as though Hans had a facility — by flying on the back of a goose high above the earth — to see everything as it was and, to some degree, as it was meant to be: simultaneously.

Seeing things from up above turned me inside out, though sometimes I think it happened the other way around. It’s not weird, I eased into it — I can talk about the practice another time.

If I were developing a Psychology-of-Self Inventory (PSI) I would include a question or two about vision — ask everyone to say how (and what) they see, and show all work as required in math.

I’m still bothered by the number of people who spew anger into the face of others because, they say, life has cheated them.

A woman I know comes to mind — Freud would love her — she never laughed or smiled. When I saw the extent of her sorrow, I took up my pen and wept.

I hope this doesn’t sound like it’s coming from another world.

At Starbucks today I spoke to a young barista named Mimi. I said: Mimi, you’re like the Mimi in “La Bohème,” a beatnik in love with all that’s love and the fanciful flights of dreams: She got TB and died.

At her last breath Puccini has the orchestra blast forth a thunder darker than the Dies Irae — I think it’s the Buddha speaking.

If someday you wonder who your grandfather was — I’ve told you once or twice — well … maybe even this is premature.

In the evening when the sun is down, I read a bit before the lights go out, buzzing like a bee inside a flower.

Some nights I can’t sleep because the day’s events and what’s in store have me watching one second pass by another.

The genius of my self is the way I see — which sometimes shows in the form of an assassin: but I always get to sleep and, in the morning, feel like Jesus on Christmas Day.

August 16, 2022

4:39 p.m.

The Ville

Happy 19th!

I’m still surprised at how few Christians, especially Roman Catholics, have heard about the spiritual writer Madame de Guyon — though small groups of believers practice the prayer she taught.

I came upon Jeanne-Marie years ago when I was writing a book-length essay on the Trappist poet Thomas Merton who prayed the way Guyon did. Though living three centuries apart, they would have made an interesting couple, comparing notes on what it takes to be happy.

The public became aware of Madame De Guyon’s ideas in 1685 when her mini-tome “Moyen court et très facile de faire oraison” appeared. In English it’s: “A Short and Very Easy Method of Praying.”

Part of the reason Guyon has been swept under the rug of Christian consciousness is because of the style of prayer she advocated. The Roman Catholic Church condemned her as a “Quietist,” a heretic they went after with bilious venom.

It was an economic matter: Guyon and her acolytes were drawing customers away from the Catholics: People liked the concept, the method, and the results her Moyen court produced.

It’s hard to say exactly how popular she became but popular enough that the hierarchy of the Catholic Church began to surveil her, and later took her into custody.

Guyon said the most direct way to be in touch with God is for a person to sit and listen — for a period of time each day, day after day, as a way of life — in total silence. She said in the depths of silence is the depths of the soul and that is where God resides — quite different from the person who says God tells him what to do — a neurotic projection.

Not long after Guyon’s book came out, it was filed in the stacks of books the Catholic Church forbade all Catholics to read; it was called “the Index,” short for Index Librorum Prohibitorum, which needs no translation.

As a kid, I recall going into our parish rectory for some reason or other and there, right in front of me in the foyer of the priest’s house, was a tall glassed-in bookcase that housed the Index; a sign on the glass said so; I have no idea who collected them.

Such a prohibition would be laughed at now, a lot of people saying: Who the hell is some bishop to tell me what I can and cannot read; hey, I watch porno on the internet!

The Catholic Church hierarchy said anyone who read one of those books was going to hell and to prove it on earth, they had their ecclesiastical police drag transgressors to the church station-house to be questioned by one of Torquemada’s kin.

You’d think the work was “Das Kapital” or Mao’s “Little Red Book” even “The Anarchist Cookbook,” or the in-the-works, “How I Led a Violent Insurrection Against My Country, Went Unscathed, and Made Millions.”

Guyon says people by nature are “called to inward silence” and that prescribed vocal prayers detract from it. She intimated that in silence a person can find “that self,” as Kierkegaard says, “which one truly is.” All religions are based in psychology.

Nancy James, a serious student of prayer and of Guyon’s life and method, put together a beautifully-arranged, -written, and -edited “The Complete Madame Guyon” (Paraclete Press, 2011). The introduction is a touching portrait of Guyon’s life before the quiet — she was married, had kids, etc. — and why the Roman Catholic Church shut down a peaceful woman who all she wanted in life was to sit and speak to God.

James said the Church lost its mind because the “hierarchy feared this popular movement [Quietism] … was attracting so many to a spiritual path that did not need the mediation of the clergy or bishops.”

To be saved, Catholics had to go to Mass, receive the sacraments, pray the “Our Father” and “Hail Mary,” memorize a catechism of questions: That came with the answers! Guyon said all that was unnecessary.

She also said meditative reading can enhance the silence but, to be effective, the aspirant must withdraw from the marketplace, factional politics, and obsessional consuming — to simply sit and read and render thanks for living.

French monastics called this set-aside time l’examen particulier — the particular examen — when a person assesses how well he or she or they are doing that day. Did they grow more? Were they good to others? Had they heard the voice of God?

Guyon said the aspirant should pick, “some strong abstract or particular truth” and read, “two to three lines and look for … the essence of the passage,” find the truth therein.

Does this sound heretical? Like something someone should be locked up for?

Jeanne-Marie became a hit in Paris but, while she and her followers were practicing Zen-like silence, the Roman Catholic Church sicced its police on her, arrested her, locked her in an airless room in a convent, and quizzed her like she was Judas Iscariot.

Nine months later, without an evidentiary leg to stand on, the fascists let her go, but did not release her from the cross-hairs of their long gun. On June 8, 1698, she was back in jail, this time by order of Louis the XIV — a favor to the Catholic hierarchy — they locked her in the Bastille of Le Quatorze Juillet.

They put her in solitary, interrogated her, threatened her with other forms of torture. The charge? Praying in quiet; living the life of a contemplative wanting to be a better person.

She was released from the Bastille in March 1703, again charged with nothing but being a pious old lady seeking to be with God. Her daughter took her in; she was 70 and feeling the effects of prison.

She wrote about it in a personal book that came out in 1772, fifty years after she died. The title page is truly 18th-century and worth sharing in full: The Life of Lady Guion, Now Abridged, and translated into ENGLISH, Exhibiting her eminent Piety, Charity, Meekness, Resignation, Fortitude and Stability; her Labours, Travels, Suffering and Services, for the Conversion of Souls to God; and her great Success in some Places, in that best of all Employments on the Earth.”

It continues: To Which are Added REMARKABLE ACCOUNTS of the LIVES OF worthy Persons, Whose Memories were dear to Lady Guion. BRISTOL: Printed by S. Farley, in CASTLE-GREEN. MDCCLXXII.

Toward the end of the second volume, she addresses those who harmed her: “I forgive those who have been the cause of my sufferings, from the bottom of my heart, whatever they have done against me, having no will to retain so much as the remembrance thereof.”

She says it all started when a friend saw her notes on prayer, read them, and took them to share with others; Guyon says, “Everyone wanted copies. [The friend] resolved … to have it printed.” Guyon said she received all the “proper approbations” from the Church, there was no mention of heresy.

Guyon said the work, “passed through five or six editions; and our Lord has given a very great benediction to it. [But] The devil became so enraged against me on account of the conquest which God made by me, that I was assured he was going to stir up against me a violent persecution. All that gave me no trouble. Let him stir up against me ever so strange persecutions. I know they will all serve to the glory of my God.”

They were the same people who killed Jesus.

I’m not a social psychologist but I venture to say America is suffering from a dystopia complex that’s manifesting itself in national malaise.

People don’t use the word despair anymore but America is suffering from despair as well that manifests itself in anger. The cocktail of malaise and anger has people reaching for guns when they feel wronged.

A number of folks told me they like shows like the “Handmaid’s Tale” and other depictions of a fascist society, which the late great sociologist Erving Goffman called a “total institution” and Hannah Arendt totalitarian society.

I do not know if young people today, or people of any age, read Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” or Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” stories of societies where people’s choices are made for them: by the State, corporate entities, or some zealous prelate — the nightmarish life of an automaton.

And when I meet people who relish such darkness, I ask why, and they never have an answer.

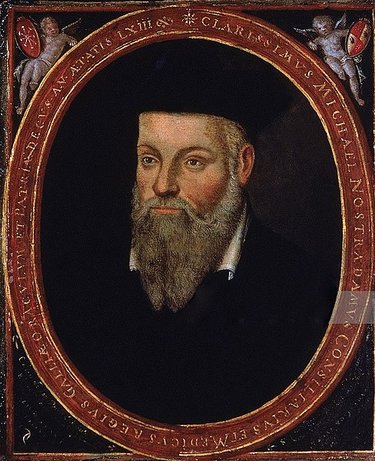

Nevertheless, I’ll offer a few Nostrodamic predictions from my dystopian “Faithless New World: Two Thousand Thirty-Five.”

My Number One prediction is: Within the next decade or so, the American experiment called The Democratic Republic of the United States will be done for. It’s already gasping for air with social arrangements that divide more than heal.

It’d be worthwhile for the U.S. government to fund a study on how the Italians became a fascistic nation under Mussolini — they sure were Julius Caesar’s kin.

Number Two: There’ll be great migrations of people from the western part of the country and down south, ousted from their homes by drought or fire or overwhelming heat; when California goes dry, millions and millions of Americans will head east like pioneers in a wagon train.

Number Three: When it comes to governmental elections — at all levels — illusion-based factionalists will reach for their guns to pick a winner. A few weeks ago, Lee Zeldin, New York Republican candidate for governor, was attacked on stage by a guy with a blade, letting Americans know democracy is a no-go.

In some areas there won’t be elections at all.

Number Four: The great migrations from drought-ridden states and those torched by unquenchable fire — multitudes on the run — will aggravate the ethical divide that exists in the country, further mocking “America the Beautiful.”

That is, Americans who reject — even scorn — involvement in “community-making” will more boldly declare: This is mine and will stay mine, and that Second Amendment you see hanging from my hip says so too.

And, because we’ve stopped making community for so long, we’ve lost the competencies that come with it — the methods, techniques, strategies that facilitate accommodating difference without resorting to violence. Becoming involved in a community group like the Kiwanis is a thing of the past.

Thus, Americans know more about Maury Povich than what families, countries, individuals, local communities need to do to flourish. On July 20, Bloomberg News posted a bulletin saying Americans are migrating to Europe because they can’t afford to live here anymore.

Another study that needs doing therefore is: What’s the cause of America’s worries, and what’s the relationship between those worries and despair? We can easily develop a Happiness Quotient Inventory (HQI) to assess the depth of America’s neurosis and her willingness to change.

That is, if I brought in 10 judges right now — noted for their no-horse-in-the-race Solomonic wisdom — and asked each to size up the health of America’s institutions — rate them from 1 to 10 — and come up with a composite of how good Americans feel about being alive, how much family, church, workplace, school, even national pride affect their well-being, and how confident they are that — when things go wrong — the guy next door and people down the street will come running like a fire brigade.

That’s what Robert Putnam was talking about in “Bowling Alone” whose subtitle reads: “The Collapse and Revival of American Community.” Putnam said America was breeding isolates, a condition for mass-shootings.

Dystopians know all about the collapse part and, while continuing to whine, refuse to administer the mouth-to-mouth America needs to resuscitate.

I won’t say boning up on these matters is summer reading, though it’d work for some — the ideas need a quiet place for pondering and study groups to discuss the conditions of a happy society, the feeling of being connected and looked after, of believing one’s dependencies (needs) will not be greeted with grudge-filled resentment.

Which is to say that, when Utah is asked to take in 11 million Californians arriving like dust-bowl Oakies, and Mississippi two million, how will Utah respond? What will Mississippi say? A sharp-mouthed cynic would say: Them down-home folk don’t even spend on their own.

I looked at what Mississippi spends on educating its young; they’re fifth from the bottom in how much states encourage kids to expand their vision beyond the kitchen door; Utah is last.

The DODS, the Diaspora of Displaced Souls, will need jobs, a place to live, a school for the kids (that’s somewhat culturally sensitive), a feeling of being at home because the guy next door and neighbors down the street helped heal the pain of a trip that started from nowhere.

We must never forget that the Diaspora did not cause the drought, the wildfires, or killing heat — we all cause them. We cannot treat them like some do rape-victims: Hey, lady, you asked for it!

Number Five: There’ll be a mass shooting every week — we may be there already — the non-stoppable collapse of a dying body-politic, the way a body disintegrates, afflicted with muscular dystrophy.

Never mind red states and blue states, the new criterion will be just states and unjust states, just communities and unjust communities, the same for families, schools, places of work — even intimate personal relationships.

Over the years I’ve been involved in discussion groups on justice at all levels and, when appropriate, have asked someone in the group: Well, do you consider yourself a just person?

It always brought puzzlement; the thought of being just versus unjust, or being a stooge for Mussolini, is not part of America’s patois.

In school, kids do not collaborate so they lose out on the practice of community: I’m talking about two of them — even a group — working together all semester, doing exams together, the same homework, getting the same grade. One for all, all for one.

Years ago I taught a course at the State University of New York at Albany — twice — called “Utopia,” in the once-exalted School of Criminal Justice. We looked at societies opposite that of the handmaidens’ Gilead.

A few people asked what a course like that was doing in a School of Criminal Justice.

I said: If a person is interested in ridding society of crime, and harms that tear a society apart, he, she, they need to find examples of social life where everybody gets along, where the needs of all are met, where no one feels compelled to shower a neighbor with bullets because they feel cheated by life.

As the great American poet, Williams Carlos Williams — a revered physician by day — used to say: People can’t speak about these things because they do not have the words. The beginning of his great epic “Paterson” goes:

The language, the language

fails them

They do not know the words

or have not

the courage to use them . . .

they say: the language!

— the language

is divorced from their minds,

the language … the language!

What a mess erupts these days when people start talking about what is, and what is not, funny. America’s funny bone has become a raw bone. In some circles, making a comedic faux-pas deserves life without parole and no thought of forgiveness.

Last month, David Weigel, a political reporter for The Washington Post retweeted something he found funny. The original Tweet was: “Every girl is bi. You just have to figure out if it’s polar or sexual.”

The post was made by Cam Harless whose website “camharless.wordpress.com” describes him as: “Writer. Husband. Father. Follower of Jesus. Barbarian.” A puzzling farrago.

Never mind finding the joke funny, Felicia Sonmez, a colleague of Weigel at The Post went on Twitter and started to shout: are you kidding! that’s outrageous! NF! [My exclamations; my paraphrase.] When seeing her words in print, I feel the ire.

Then Sonmez started going at The Post in front of the world: She tweeted: what kind of paper allows a reporter to make fun of women like that! [More paraphrase.]

I wondered if anybody in management thought the joke funny.

Weigel saw what was going on; not wanting to get into anything, he went back on Twitter with: “I just removed a retweet of an offensive joke. I apologize and did not mean to cause any harm.”

And I wondered, because so many people make false apologies these days, if Weigel, despite his shared regret, still found the joke funny: he just wanted people off his back.

I see humor in the joke — from a certain cultural comedic frame of mind, it’s funny.

Of course The Post weighed in. The paper’s chief communications officer, Kristine Coratti Kelly, got on the tweeter-horn — the mind-shaping-instant-opinion-forming network — and said, “Editors have made clear to the staff that the tweet was reprehensible and demeaning language or actions like that will not be tolerated.”

Id est, management’s vote was: not funny.

But I haven’t seen where the paper spent time explaining to staff its position on funniness and laying out what it, as a political-economic institution, will not tolerate in its workers.

Those who have studied the nature of sincere apology would say The Post offered a standard by-the-book version, the best a capitalist institution can do, even one with a motto: Democracy Dies in Darkness.

Before I accept the Post’s apology I want to see the results of a two-question questionnaire they’ve administered to every employee, the first question being: Did you find the joke funny? The second: Why did you say yes or no to the first question? And, as in math, show all work, your ethical thinking.

Did any boss at any level say to any staff member at the paper that keeping his job required him to espouse a particular comedic frame of mind — pointing out exactly where “the line” is, and what happens to those who cross it?

Here’s the update: Despite his remorse, Weigel was suspended for a month — no pay. [Where does a guy like that come up with next month’s rent?]

Sonmez kept at it, pulling her colleagues into the fray. They started tweeting their views on funniness, whether Weigel was right, and whether a paper is responsible for training its workers properly. For a day or two, Twitter was a Wapo warzone.

I had, and still have, no quibbles with Sonmez’s view. It’s worth discussing. It’s the means she took to deal with the hurt. She went to the world on Twitter to find relief rather than walk down to HR and demand a meeting of all staff — top to bottom — to discuss what is and what is not funny, what people at the paper can and cannot say, and what the paper’s responsibility is for worker deportment — even the guy in the mailroom.

That is, rather than deal with the issue structurally, Sonmetz blazoned her torch on Twitter. That’s not to say her point of view should not be available to everyone, it’s that she went for “the show” and not for policy elucidation and structural change.

And I have not seen anything that says The Post has taken action to delineate what people at the paper can and cannot say.

The other sad part of the story is that on June 9, The Post fired Felicia Sonmez. True. They said it was for, “misconduct that includes insubordination, maligning your coworkers online and violating The Post's standards on workplace collegiality and inclusivity.”

Violating workplace collegiality means Sonmez, and those of her mind-set, failed the section of the Miss Manners course on “cooperative workplace.”

How will Sonmez come up with the rent for who knows how long? And, according to the book, canceling someone is not a show of collegiality, it’s a failure in leadership.

When she went on Twitter, the paper needed to call her in right away, slow her down, say they were ready to listen but wanted her first to sit down and write out all her thoughts. And because they needed it soon, she had time-off to do it — with pay.

And the paper needed to say it would convene a synod — to which every Post employee was invited — where there would be discussed the difference between a funny that relieves pain and a funny that causes it, at least more pain than it relieves.

Which is the measuring rod of ethical comedy: the relieving of pain versus causing it.

Here’s the joke again: “Every girl is bi. You just have to figure out if it’s polar or sexual.”

Funny or not funny? Why? Show all work.

One of the greatest comedians of all time, Rodney Dangerfield — Comedy Central ranked him seventh best of all time, one behind Steve Martin and right before Chris Rock — was enamored with people’s idiosyncrasies.

Playing the sad sack he kept moaning, “I get no respect.” He was always getting the short end of the stick: with his kids, his doctor, lawyer wife, girlfriends — they all disappointed. He liked fat jokes and ugly jokes.

One night on Carson, he started in on the women he met. One of them, he said, “was no bargain … she was FAT!”

And Rodney’s fans in the audience, taking the bait, came right back: “HOW fat!?”

And he, loving the joust, looked in their direction and fired back: “HOW fat? [I’ll tell you how fat] When she wears high heels, she strikes oil, OK!”

And you know what? “I met her at the Macy’s Parade, she was wearing ropes!”

HOW fat was she?! “She got on a scale, a card came out and said One at a Time.”

That’s right, “She was standing alone, a cop told her to break it up.”

Funny or not funny? Pain-relieving or pain-causing?

Rodney went at “ugly” people too. What power does anyone, whose looks have veered far from the hub of beauty, have to tackle such a trope? They were already dismissed.

George Carlin is the best stand-up comedian ever — Dave Chapelle was wrong last month — sure, George berated Americans for being absolutely stupid, unable to wake even when hit with a two-by-four. But he turned the spotlight from the idiosyncratic to the powerful — people and ideas — and, like Jeremiah, began chanting “Converte, Jerusalem.”

He took on religion, God, child-rearing, education, play, drugs, imagination, personal responsibility — the meaning of life — and exposed “the line” of acceptance, letting everybody know what was waiting on the other side.

Indeed, in 1972 the Milwaukee police arrested him at Summerfest for using the English language on stage — seven words — like he was Al Capone.

I can’t figure out if George was brutally funny or funnily brutal.

Would Rodney play today? With the fat, ugly, and loser jokes? I recently realized he was dystopian.

In this next phase of our collective existence, we’ve been called to clarify what language relieves pain and what language causes it: and how much control anyone in the future will have over what he can say about how he truly feels.

For George Carlin

DEAR ABBY: I need advice and I need it now; I’m besieged on all sides.

First of all, every time I turn the TV on, I see Ukrainian families blown to bits, some while sitting in the kitchen drinking tea with friends. Ukraine’s cities are boulevards of sunken ash.

I listen to what pundits say; they say the head of Russia is crazy, that he’s an old-time ideologue lost in a world where he projects himself and Russia as beneficent beings on the world stage when in fact, Abby, he neutralizes people who oppose him and shows little regard for the quality-of-life needs of the average Russian; Russia is close to a failed state.

His black eyes reach down to Dante’s inferno.

Not long after Russia started bombing Ukraine, the senior United States senator from South Carolina, Lindsey Graham, offered a solution. On Twitter he posted, “Is there a Brutus in Russia? Is there a successful Stauffenberg in the Russian army?”

The next day he was back at it: “I’m begging you in Russia … you need to step to the plate and take this guy out.”

He was clearly aping: “Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you find the 30,000 emails that are missing.”

Such pleas are acts of treason in that leaders of a sovereign nation are asking citizens of another sovereign nation to intervene in a nation’s future, to transgress the geo-political-cultural boundaries that allow a nation-state to be a sovereign.

How different was Walt Whitman’s America — he called it a “Body Electric” — the converse of the dystopian virus infecting America’s heart today.

In his poem “To Foreign Lands” Whitman does not ask a foreign power to intervene in America’s future but points to her vibrancy as an “athletic democracy.”

In the poem, he tells the leaders of the world, “I heard that you ask’d for something to prove this puzzle, the New World,/And to define America, her athletic Democracy;/ Therefore I send you my poems, that you behold in them what you wanted.”

What nerve. Telling the world that his “Leaves of Grass” is the true heart of America, a benevolent sovereign that takes into account the needs of the very least (without resentment).

Nowhere does Whitman encourage the fox to enter the hen house.

And he never called for civil war the way the past president of the United States keeps doing — he was in a civil war, and heartbroken that America was resolving her differences with one side shooting the other down.

And though he was 41 when the war began, Walt signed on as a nurse; he went into hospitals and talked to soldiers who’d lost an arm or a leg; he wrote letters home for them — some to a sweetheart — and gave absolution to those tortured by guilt for having killed a soul from the next county over.

Like a teddy bear, he hugged the men; he gave them kisses on the cheek, he called it manly love. Like a good shepherd, he never sought a nickel in return.

“One Sunday night, in a ward in the South Building,” he tells us, “I spent one of the most agreeable evenings of my life amid such a group of seven convalescent young soldiers of a Maine regiment. We drew around together, on our chairs, in the dimly-lighted room, and after interchanging the few magnetic remarks that show people it is well for them to be together, they told me stories of country life and adventures, &c., away up there in the Northeast.”

Whitman’s America is what Norman Brown means by Love’s Body, a collective soul that burns so bright with kindness that it treats its least as the very best — without resentment.

The Stauffenberg who Lindsey Graham mentioned was Claus von Stauffenberg, an officer in the German army during World War II. On July 20, 1944, he became world-famous after he tried to kill Hitler with a bomb.

While Hitler was meeting with his staff, Stauffenberg slid a suitcase under the table packed with a bomb; it went off and three officers were killed; the thickness of an oak table saved Hitler from demise. His pants were blown to shreds.

Stauffenberg had tried it before but something always happened and Hitler went unscathed. He himself helped with the cause on April 30, 1945.

After the failed assassination, Stauffenberg and three comrades were arrested; they were shot dead before the next day’s sun rose.

In Berlin today, there’s a museum called the German Resistance Memorial Center that celebrates Strauffenberg and every other Nazi resister from 1933 to 1945.

Abby, tell me: Can a person be a hero, be without sin, for killing another for ideological reasons?

The memorial center is located on Stauffenbergstrasse [sic] and opens onto the quadrangle where Stauffenberg and his comrades were shot as enemies of the state.

In 1944, it seems some Germans had a vision of a Germany that resembled Whitman’s America when “Leaves of Grass” appeared on July 4, 1855 — a homeland teeming with largesse.

As soon as I heard Graham mention Stauffenberg, I was brought back to my youth when we played a game called “Would You Assassinate Adolf Hitler?” It was me, my cousins, and a brother — I do not think it was at school — but I remember the “game” as clear as day.

We asked each other: Would you do it? Would you take the Führer out, especially if you could get away with it? I don’t remember what we said but we were Roman Catholics and the Catholic Church said transgressing the sovereignty of another’s person was murder, a mortal sin for which the sinner would spend eternity burning in the fires of hell. The forever-and-ever part was always stressed.

When one of us waffled with an answer, he was asked right away: OK, what if you knew that, by assassinating Hitler, you would save the lives of three million Jews — and never be detected — what does your Catholic Church say about those odds?

It’s a radical means-ends question, and economic in nature because it deals with the worth of one thing/person/community/nation over another. I’m fascinated with the dilemma still: Can a person be a kamikaze pilot for Jesus?

Are these the kinds of questions you’re dealing with these days, Abby? Are you up on the political-economy of nation-state sovereignty? How would you handle a man who calls for civil war?

And what about all those shootings where kids in schools and Black people buying cereal at a supermarket are taken out, desecrating Whitman’s body-electric America? I think it means the civil war has begun.

In my Orwellian moments, Abby, I project that someday there’ll be a museum on Drumpftstrasse [sic] in some southern parish featuring Donald Trump as a Stauffenbergian hero for trying to kill the vice president of the United States, Mike Pence, for opposing his fascist regime.

The more America’s Whitmanesque face-to-face communities disappear, the more isolates take up guns to settle differences. It’s a Euclidean axiom: The less face-to-face, the more the gun.

And when you write back, Abby, please tell me if there’s an elixir I can take to heal my despair.

I came out with a new book of poems this past Christmas called “Thirty-Two Views of the Face of God.” It was a gift for my friends.

As you might imagine, the title is problematic in that millions of people believe that a person cannot see the face of God, that it’s beyond human ability — their religion says so.

Christian genealogists trace their thinking to John the Evangelist who says in the Prologue to his gospel: No one’s ever seen God. Zero-sum.

And, if you read the New Testament (the Greek Scriptures) you know such thinking exists in Paul. In a letter to a group of young Christians in Corinth, he tells the neophytes right off that happiness is seeing God face-to-face and that we, in our bodily state, see only “through a glass darkly.” A human being is fully happy only after death.

It’s a bold assertion because it sets the parameters of human potential, defines the psychological dimensions of personhood, and maps out a person’s path to happiness.

Thomas Aquinas and theologians of his ilk refer to seeing the face of God as the “beatific vision” and reaffirm John’s assertion that it’s a human being’s raison d’être.

Such thinking is clearly at odds with the work of the great psychotherapist Carl Rogers who spent his life working with people who sought relief from their unhappiness. His “On Becoming a Person” is a collection of essays about people revealing their stories and experiencing a new sense of “divine.”

The odd thing about seeing the face of God is that, if I sat down 10 believers right now and asked each to describe it, they would be perplexed, dumbfounded. And they have to do it in detail: A face has features. What are its physical properties? Or is the face of God an invisible nothingness?

Without some sense of what to look for — as the late comedian Jackie Mason might say — you could wind up with the face of a wrong God.

And — for the conventional believer — dealing with these issues is far beyond the power of the conventional sense of “faith.”

You can see why “Thirty-Two Views” stands in opposition to John, Paul, Thomas Aquinas, and others who set the parameters of human happiness outside the human; without human grounding, happiness could easily be mistaken for smoking crack.

If the gospel writer John were here, he’d say with a snip: “I already told you: No one’s ever seen the face of God! And here you’re telling me you have thirty-two views. Infidel!”

And I would say: “No, John, these poems reflect actual visions or experiences that took place beyond the edge of human consciousness — where poems are born — expressions of what some poets call the voice of God. And because you say, John, no human being can see the face of God, you have no data — while in my little book, I offer 32 graphic captions of what that face looks like in its own language — poetry.”

At the end of the “Poet’s Preface” in my little book there’s a poem I wrote in Spanish called “El Evangelio Según San Yo” which in English is, “The Gospel According to Saint Me,” and saint not like those in Butler’s “Lives of the Saints” but like those evangelists who speak of the divine’s human dimensions.

I started thinking about this in Barcelona when I bought a copy of the “Collected Poems” of the Spanish poet José Ángel Valente. In the back of the book Valente offers his Spanish of the Prologue of the gospel of John: “El Evangelio Según San Juan [Prólogo]” “The Gospel According to Saint John [the Prologue].”

Valente translates John’s dictum as: Nadie jamás ha visto a Dios — nobody’s ever seen God—words I read in Greek 60 years before but never saw their subversive nature, how they turn happiness upside down.

In the middle of my poem I say (my translation of my Spanish):

But what grates me most

Is the pen of the propagandist John

Who Catholics call a saint

Who apostatized saying

No one’s ever seen the face

Of God.

While my heart smiles all day

And at night laughs beyond control

Because the stars never expire

Just like the moon and the sun.

Rogers would like that, the author of his own Upanishads.

And, if a person cannot see the face of God, and it’s central to his religion, he must imagine it. A face is a visage and visages are images that have words: eyes, nose, placidity, contemplative.

I might add that a few people — two to be exact — expressed concern about the first two sentences of my Poet’s Preface which read: “If I told you all I learned in life, it would take a million years. I still surprise myself.”

One of my friends said I was coming across as some kind of Renaissance man. But the words mean that, when a person starts telling the story of how he relieved himself of burdens and entered into the divine, it takes time.

If I asked you: Tell me everything you know, how long would it take? A minute? An hour? Most of the day? Would it take a million years?

My hypothesis is: Detailing one’s transition from one stage of growth to another is a source of happiness, and arranging the narratives of all those transitions into a harmonized whole is a view of the face of God.

Rogers said, when people come in for therapy, they come behind a façade, behind which they hide their face and everything else of value. Thus, my second hypothesis is: Those who cannot see their own face because they keep it hidden behind a façade, are unable to see the face of another, never mind the face of a being they bet their happiness on.

Rogers also said that, when folks begin to feel safe in therapy, they start saying things they never knew were inside them, and their face lights up with the light of another world.

If you were asked right now to tell everything you learned in life and how it’s made you happy, should I pencil you in for an afternoon or will it take a million years?