Freud’s question is relevant today: Can society rid itself of the aggression that’s killing it?

In 1930, the small publishing firm of Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith came out with the first English edition of Sigmund Freud’s “Civilization and Its Discontents.” The book was a kind of Dear John billet-doux to humankind.

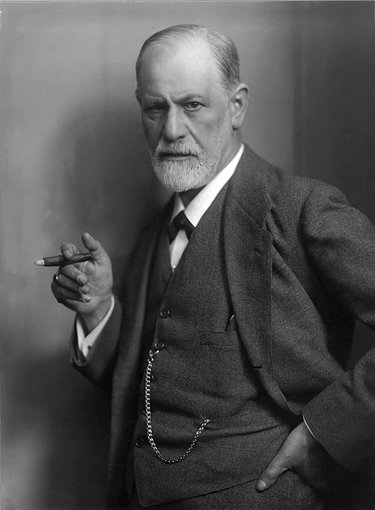

Freud, the father of psychoanalysis — the man who sought to understand why human beings find enjoyment in repressing themselves — was wondering whether a civilization, a country, or any social relationship that’s in psychological trouble, can actually rid itself of the aggression that’s killing it.

Three years earlier, when his celebrated “The Future of an Illusion” came out, Freud asked the same question but on a “spiritual” level. He was wondering what kind of psychological succor formal religion can offer a person to get through the day; on a larger scale help that person find meaning in life; and on a still larger scale, help him understand the structural conditions, the social institutions that deny succor to some because of the way they look or think or maybe they’re not a boy or a girl. And the succor is always offered at a price.

I would not recommend “Discontents” to everyone because it contains a lot of mind-testing words from the Freudian lexicon, but the book’s persistent query is: Is it possible to live without aggression toward others (in word and deed)? Why do so many feel compelled to carry a six-gun?

I just finished re-reading “Discontents” to celebrate its 90th birthday this year. The odd thing is, I feel Freud could have written the book about the United States of America today where aggression runs so high that half of the population can’t talk to the other half without waving a stick or carrying a six-gun.

Freud said the questions about discontent and how we might free ourselves from its ravages are “fateful,” that is, they affect the way we live now and well into the future.

He said the “the human species” may never reach a point of “cultural development,” that is, develop the necessary tools, to respond to “the disturbance [that’s affecting our] communal life.”

We’ve “gained control over the forces of nature,” he said, and some people seem ready to use that power to exterminate “one another to the last person.”

I’m sure his tone was affected by the late-1920s Austria where the political left and the political right clashed in the streets. A right-wing paramilitary group, the Heimwehr, decked out in Tyrolean fedoras, could be seen, gestapo-like, parading through Vienna seeking to destroy socialism. A “revolt” took place in July of ’27 where 89 protesters were shot and killed; five policemen died; it is said 600 protestors and as many policemen were hurt.

History tells us Freud was right in using the word “extermination.” In Germany’s September 1930 election — the year “Discontents” came out — the Nazis won 107 seats on the German Reichstag.

On the day parliament was seated, the 107 came dressed in brown military shirts. When the roll-call came to them, each shouted “Present!” punctuated with “Heil Hitler!” Every Jew in Austria could feel the coming Lebensraum.

I’ve been in conversations where the topic turned to people’s likes and dislikes — “I like vanilla ice cream better than chocolate.” “The Yankees are better than the Mets.” “Black and white movies have it over color.” — and, when appropriate, I have asked someone: Do you hate anybody? And if you do, do you do it without guilt?

A reporter recently asked the Speaker of the House of Representatives of the United States Congress whether she was telling the truth when she said she prayed for the president, a man who makes fun of her face and calls her crazy. Does she hate him?

Nancy Pelosi blared: How dare you! Christians do not hate; the basis of our religion is: We deal with disrespecters with dignity. She did not mention Gandhi’s: “Do not fear; he who fears, hates; he who hates, kills.”

If Freud were analyzing the insidious neurosis afflicting the United States today, he’d say its people lack tools, interpersonal tools to get along with each other, and psychological-insight tools to envision a future without aggression — a place where everybody benefits, where everybody’s needs are treated like everybody else’s.

I once was a mediator in the Albany County courts, the small-claims division. When contestants accepted the offer of the judge to go off and reach a mutually-satisfying agreement face-to-face, they and I went to the jury room next door.

I sometimes felt like a marriage counselor for a couple whose righteousness had blinded them to the point they saw each other only as an abstraction.

Minutes before in the courtroom they were saying: Your honor, my opponent is a fool, and the fool would respond: Your honor, talk about fools!

In the mediation room, I quickly had to establish rules that disallowed using words that denied the other’s worth, indicating that mediation works when each person agrees to speak to and listen to the other as an equal.

In almost every case, as happens most times in mediation, things got worked out but I could see that the contestants never really bought the equal-value notion. They just didn’t want to go back to court and have the judge make the decision.

Of course every being can speak and every being can listen in some way but speaking to and listening to another as an equal requires a sharper set of tools, laser-sharp analytical competencies.

In restorative-justice sessions, when someone wishes to apologize to another for the pain they’ve caused, it sounds ridiculous but they have to be taught how to speak, to understand that what they say might cause further harm. The examples are endless.

Three years after “Discontents” came out, the Nazis started burning Freud’s books. Herr Professor told his colleague-friend and later biographer, Ernest Jones, “What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.” Therapeutic irony.

It’s in the last paragraph of “Discontents” where Freud alludes to the possibility that human beings might “easily exterminate one another to the last man.” He said the fear of that causes “a great part of [our] current unrest, [our] dejection, [our] mood of apprehension.”

He said it comes down to whether Eros — Love — will be able to muster the “strength ... to maintain himself alongside of his equally immortal adversary,” Thanatos or Death, which manifests himself in the degrading way we speak to and act toward each other. Ladies and Gentlemen et al, America is not a happy place.

Freud felt compelled to add a final sentence to “Discontents” in the 1931 edition, “Aber wer kann Erfolg und Ausgang voraussehen?” Bob Dylan translated it in his 1967 anthem “All Along the Watchtower”: “There must be some way out of here ... There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief.”