Unfiltered: Booksellers whose love for books governs their being

— From Cornell University

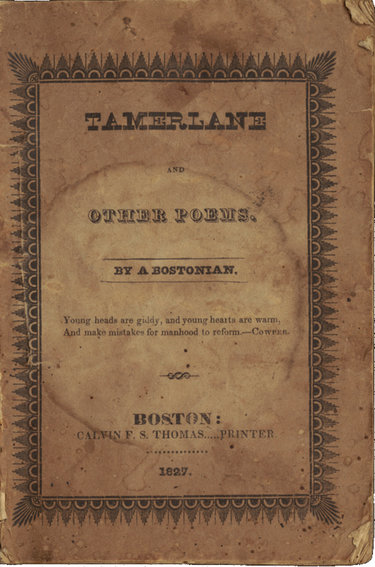

Only about 12 copies of “Tamerlane,” the first published work of Edgar Allan Poe, are known to exist. This is the most recent one found — in 1988 in a New Hampshire antiques sore, purchased for $15. It is now in the Susan Jaffe Tane Collection at Cornell University, the largest privately-owned Poe collection in the world.

At the end of February 1988, a Massachusetts man, a fisherman — who would not be identified — came upon a copy of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Tamerlane and Other Poems” in an antiques barn in New Hampshire. He had been looking through stacks of ephemera — pamphlets, catalogues, and the like — and there was “Tamerlane.”

The man recalled having read about it and thought it worth something. At the time, he told The New York Times, “It rang a bell in my head. I was alone. I got very excited.”

It cost $15.

The next day, he was off to the Sotheby’s office in Boston, book in hand, to ask the staff of the elite auction house what they thought. They said he had a gem; in March, they were telling reporters they thought the book would bring in the many high thousands.

In June, “Tamerlane” came up for sale and went for $198,000, dirty cover and all; it has a ring on it as if someone used it as a coaster.

The buyer was the well-respected New York City antiquarian book specialist James Cummins. He never flinched at the price; he said he already had it sold.

Cummins is among those book specialists around the world who view “the book” as a cultural artifact, a work of art, and the more unique the work — limited signed first edition, jeweled cover — the more a certain subset of book-lovers are willing to pay big prices for it — to a known dealer or a scout who found it in an attic or barn, like the fisherman — but they know what they’re looking for.

Almost as if to defend that genre of bibliophile, the artist/writer Maurice Sendak said, “There is so much more to a book than just the reading,” which explains the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School. There, they offer courses like “Introduction to the History of Bookbinding,” “The History of the Book in America, c.1700–1830,” and “The Handwriting & Culture of Early Modern Manuscripts.” Twenty-two hours of class cost $1,000.

But there is another subset of book phile, says the late A. S. W. Rosenbach — considered the greatest antiquarian bookseller of the 20th Century — whose members are taken over by circean lust. In his semi-autobiographical “Books and Bidders” (Little, Brown, 1927), Rosenbach says he had “known men to hazard their fortunes, go long journeys halfway around the world, forget friendship, even lie, cheat, steal all for the gain of a book.”

Cummins, Rosenbach, Tamerlane, and every facet of the rare and antiquarian book trade are presented in D. W. Young’s recent (March 2019) enchanting documentary “The Booksellers,” available on Amazon Video.

Greats from the antiquarian book world show off gems like proud parents. They describe the psychology of what hooked them as well as that of collectors who live for “the find.” But everyone in the movie is so disarmingly honest, they seem like simple monks. They have no filter.

Of course they’re involved in a business but their fascination with and love for books govern their being. It would not be the same with baseball cards.

They know everything about a particular title or even the entire oeuvre of an author: the editions of each book; the paper quality; the stitching of the binding; cover-design; even the watermark — the image a paper mill presses into each sheet that’s (mostly) unnoticeable until you hold it to the light. Today, it’s mostly the company’s logo or percentage of rag in the paper.

For my graduate degree in classics (Greek and Latin), I had a course where we spent considerable time examining the watermarks of atlas-folio-size sheets hung on a line the teacher strung across the room. [A Jesuit from Fordham.] [I could not get enough.] [I was in my twenties.] [Giant sheets of Gregorian chant.] [Incunabula.] [Appreciation of the beauty of the package words come in.]

I’d recommend “The Booksellers” to every booklover there is, but I do not because there are so many strata in the category of “booklover” today.

I know readers of Danielle Steel and James Paterson who say they love books. I know people who read Orwell’s “Homage to Catalonia,” Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath,” Susan Sontag’s “Against Interpretation,” and John of the Cross in Spanish and say they love books.

And I know, and have met those — I owned a used-books store once — who lust after jeweled bindings and first editions and say it’s because they love books — the text incidental.

I suppose the crooks who made off with the great Gospel of Columbkille in 1007, its cover bedecked in gold and jewel, considered themselves booklovers too. But when the tome was recovered, the gold and jewels were gone — the crooks hadn’t read the words within.

The cognoscenti say “Tamerlane,” 40 pages long, was expensive because it came out in 1827; only 50 copies were made; it was Poe’s first work; he wrote it as a teen. And only a cognoscentus would know it was by Poe because the author page lists the poet as “a Bostonian.”

For those who like the money part, in 2009 Christy’s sold a copy of “Tamerlane” for $662,500. It was the most ever spent for a book of American literature; James Cummins called it a “black tulip.”

I love books; I’m not a collector but I buy only cloth, and those fitted with a jacket; I want to know how the publisher depicted the author’s vision.

I also look at the paper quality of a book; I consider how the binding’s stitched; I assess the index, and how easily the print sits on the page; I love words, and especially those clothed in beauty.

For some time now, a cadre of booklovers have been saying they fear the book is done for. They point to computers, Kindle, Facebook, and other paperless engines of information. They say the physicality of a text, the turning of pages — and how such a simple act allows for a second of reflection — are anachronisms.

I used to hear people say, “I’m gonna curl up with a good book tonight,” which I took to mean they were going to create a space in which they and the author would sit in a kind of bubble and converse about life — no interruptions — and explore — when books are at their best —issues of human redemption.

People say they love movies and TV because they allow for escape. But the book, thick with pages and a cover of record, does the opposite; it asks the reader to engage the world, and intimately; even with Dashiell Hammett’s “The Thin Man” somebody’s got to find out who done it.

The saddest thing about the book’s lessening presence in our lives is that reflective reading is passing as well; those words, sentences, paragraphs, whole texts that encourage a person to find his purpose in life, sit on the shelf.

For centuries, Christian monks have called reflective reading lectio divina — texts that move a person to assess what he does for others, how much joy he creates, whether he helps to relieve pain and suffering — it’s really lectio humana.

Such reading requires time-away, a break from the day, a time and place to sit and think and ponder — curl up, as some say. You cannot buy a spiritual life.

In “The Booksellers” the three daughters of Louis Cohen, the late founder of the great Argosy Books in New York City — Judith Lowry, Naomi Hample, and Adina Cohen — appear as angels. I hope they live the way I think they do; then they’d be poets too.

If you’re a booklover who can look in the mirror and say: I want to know all there is to know about books, Ms. D. W. Young made “The Booksellers” for you. As they say in French: Point!