‘All American citizens are brothers of a common country’

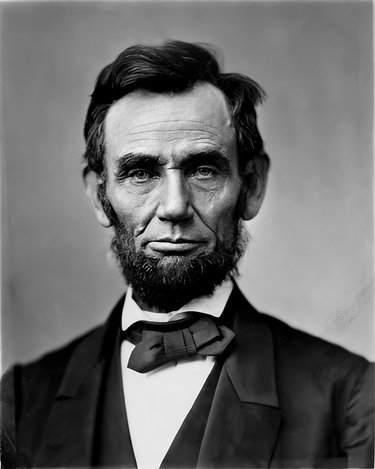

In an Aug. 7, 1863 letter to Horatio Seymour — the fractious governor of New York who opposed the Emancipation Proclamation — Abraham Lincoln stated with resolve, “My purpose is to be, in my action, just and constitutional; and yet practical, in performing the important duty, with which I am charged, of maintaining the unity, and the free principles of our common country.”

I wish Lincoln were alive today so I could ask him whether his definition of common country included meeting the needs of all, the enduring question of political economy.

“Common country” had been on his mind from the beginning of his presidency. On Nov. 20, 1860, two weeks after winning an election with less than 40 percent of the vote — a civil war waiting in the wings — he addressed a group of “Friends and Fellow Citizens” in Springfield, “Yet in all our rejoicing let us neither express, nor cherish, any harsh feeling towards any citizen who, by his vote, has differed with us. Let us at all times remember that all American citizens are brothers of a common country, and should dwell together in the bonds of fraternal feeling.”

Unity. Common country. Dwell together. Fraternal feeling. Treating others with “patient tenderness and charity,” a trait one biographer linked to Lincoln.

Any soul who’s been to therapy and cleansed his mind of the ideological constructs that sabotage happiness and drive wedges into relationships, tends to treat others with patient tenderness and charity taking their needs into account.

As a patient — coming from the Latin patior, to suffer — the “cured” soul had his story listened to with an open heart, his needs had been recognized as worthy of attention so, when he meets travelers of divergent points of view, he is able to open his heart and see their stories as valuable as his own, their needs as important as his.

When a person’s story is not heard, when his needs are denied or minimized — certainly not met — an enduring wound is inflicted on the psyche. Oftentimes the wounded soul angrily deflects the pain by projecting the hurt onto others, making them pay for the loss.

Vindictively, he speaks in ways that are divisive and argumentative, adopting what the late clinical psychologist Marshall Rosenberg called, “jackal language.” Justice for him is not meeting the needs of all equally but getting even, often in oblique ways. For decades the esteemed Brandeis sociologist David Gil pointed out how this kind of invective incites retributive counter-violence.

Carl Rogers, one of the pioneering psychotherapists of the 20th Century said on many occasions that, when people come to therapy seeking help, they arrive emboldened by a façade.

The façade was a tool, a strategy, they adopted to insure that their needs were met but they had reached a point where such walled-in existence and its accompanying jackal language were debilitating. Disunity and division were killing them.

They did not know, when they first entered the therapist’s office, that they were searching for a new identity that required digging deeper into the self. Freud described the procedure as, “one of clearing away the pathogenic psychical material layer by layer”; it was like “excavating a buried city.”

The excavation allows a patient to let go of the ideas, acts, ideologies, and all the tools that support façade-based living. All he wants is to stop the mind from warring with the heart.

The great 20th Century thinker, Norman O. Brown, was possessed with understanding what caused people to adopt divisiveness and rage as a way of life and whether such sufferers might find release through renewed consciousness.

In his 1966 classic, “Love’s Body,” Brown titled the fourth chapter “Unity.” The first sentence begins, “Is there a way out; an end to analysis; a cure; is there such a thing as health?”

That is, can a person, a society, ever heal from the wounds it has inflicted upon itself by disregarding the stories of some, by denying that their needs have validity?

Brown asks that question on page 80 and by the final page of text we see (1) there is a way out of disunity, out of psychological and societal suicide; and (2) there is such a thing as health and it can be practiced and achieved.

Brown also concludes that there is no end to self-reflective analysis and, as far as a “cure” goes, the wound never fully heals. But the struggling soul realizes, like Lincoln, that, when he recognizes the needs, stories, and history of others as equal to his own, he welcomes even those outfitted in rage into the common country. Personal value is based not on what one deserves but on what one needs.

But such an ideal is achieved only when we forego jackal language and begin to speak to each other nonviolently. The Center for Nonviolent Communication, which Marshall Rosenberg founded decades ago, offers four strategies to help a society move in that direction.

The first is to speak to each other about what we are seeing, hearing, and touching without making a judgment or evaluation. Rosenberg says, “When we combine observation with evaluation others are apt to hear criticism and resist what we are saying.” Generalizations like “You, right-wingers ...” only add to division.

The second practice is to develop a vocabulary of feelings where we point out where our needs are being met or not met. If we “clearly and specifically name or identify our emotions,” Rosenberg says, “we can connect more easily with one another.” Abstractions like “I feel I never got a fair deal” intensify anger.

Third, everything we do must be in the service of needs. Rosenberg says at the level of needs, “we have no real enemies, that what others do to us is the best possible thing they know to do to get their needs met.”

Miscommuniqués, therefore, do not call for blame or shame or hate but for reclarification. The focus should remain on the source of the hurt and the wish to be treated more fairly. Within such a framework we are all likely to express feelings and needs and forego recounting tales of past injustices and hardship.

The final prerequisite for nonviolent communication is that, when speaking to others, we make requests as opposed to demands. When a person hears a demand, he sees submission and rebellion as his options. Rosenberg says, “Either way, the person requesting is perceived as coercive, and the listener’s capacity to respond compassionately to the request is diminished.”

How well the members of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa knew that, if a common country is a goal, the stories of all must come out.

President George H. W. Bush understood this even in the face of defeat. On White House stationery, in pen and ink, he wrote to his successor on Jan. 20, 1993:

Dear Bill,

When I walked into this office just now I felt the same sense of wonder and respect that I felt four years ago. I know you will feel that, too.

I wish you great happiness here. I never felt the loneliness some Presidents have described.

There will be very tough times, made even more difficult by criticism you may not think is fair. I'm not a very good one to give advice; but just don’t let the critics discourage you or push you off course.

You will be our President when you read this note. I wish you well. I wish your family well.

Your success now is our country's success. I am rooting hard for you.

Good luck — George

Forty-One like Sixteen knew all about common country.