The deeper a person’s solitude, the more he’s connected to others

Share your reading list with me and I will tell you who you are; a reading list is food and we are what we eat.

And, if you tell me you do not have a reading list, I will tell you who you are as well: why you’re starving, and how to restock your shelves to offset the disease.

Years ago, I was editor-in-chief of an international journal on justice called Contemporary Justice Review. It’s out of the U.K., under the imprint of the esteemed Routledge, a subdivision of Taylor and Francis. It was my brainchild.

For a proposed special issue of the journal, I put out a call for papers to the academic community — as well as the public at large — asking folks to submit an essay on their moral and ethical development, that is, the emotio-socio-cultural foundation stones on which their being rested, a personalist vision of what Nietzsche was talking about in “On the Genealogy of Morality.”

Thus the writer had to reveal his overriding vision of life — concepts like freedom and justice — as well as the spiritual foundations on which his rules of life were based, his system of ethics, and because all rules and ethical systems have to do with happiness, the call for papers was essentially asking the writer to say what made him happy.

Delineating such mental frameworks is not an easy task; it requires naming the persons, places, and events that shift the axis of a person’s being and force him to build his ethical foundation anew — from the bottom up.

Thus, if a writer saw himself as a five-story building, he had to say how (and why) each floor came into being, right down to the rooms. It’s a level of self-analysis the great psychoanalyst Karen Horney championed all her life.

The special issue of the journal never came about; the response was too lukewarm — and I knew why.

First, the process is painful. The writer, explorer, thinker, analyst, must engage in a near-Marxian economic analysis of every aspect of his life — every person, place, and event — and reveal the worth he has assigned to each.

The human personality is a pool, a gestalt, of all such rankings combined. And they might be as basic as: I like pasta over pizza but, on a larger social-structural level, it’s: men are superior to women; whites outshine Blacks; fascist societies surpass those where people have a say.

And the ranking process is not some option, it’s grounded in our DNA: parents do it with their kids. They say they love their every child the same but deep down say one of the kids tugs on their heartstrings in a special way — a hierarchy of worth. A Freudian would say it’s the ego moving the soul toward Nirvana.

When a person’s rankings leak out and I’m there, I always ask how they came to be. Economics are not Marxian but arise with the birth of time and consciousness. The human being prices things like the Antiques Roadshow.

When people get old and lose their inhibitions, they say aloud — often to the embarrassment of their kids — what they think a thing is worth. Life’s clock freed them; saying their piece is a source of peace.

As a country, as a culture, America has long rejected reflective self-analysis — what do the Proud Boys read? — thus splinter groups keep springing up that lionize aggression and violence, nihilists who deny the worth of anything not themselves.

On the other hand, contemplatives — I read their work daily — speak (and write) a poetry of peace. It might not be Yeats or John of the Cross but it’s the language of mystics.

The issue of my journal never came about as well because contemplative self-reflective activity is not rewarded in the academic marketplace; it does not lead to tenure or a full professorship. Who will pay for periods of meditative reading and a space for solitude (could be a room in the public library) and, for some, a pen to log their experience?

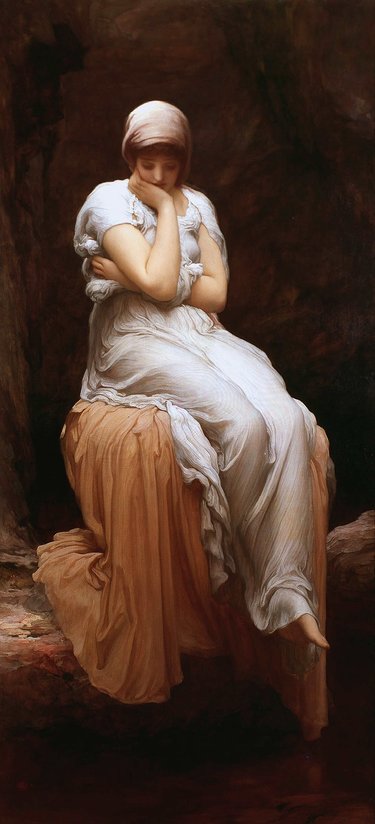

But people reject such a life because they view solitude as loneliness, with being disconnected from everything that makes them happy: phone, TV, computer, shopping. And they are partially right because solitude requires time alone.

The irony is: The deeper a person’s solitude, the more he’s connected to others — a paradox of consciousness. It translates into living in accord with “other” at every level: neighborhood, town, village, partner, mate, and family; aggression and violence are rejected as means to deal with “difference.”

The aspirant speaks of such accord with elation and strives to keep that way of life intact. Some Asian mystics say they fear no hardship because they can sever soul from body — elation as inexhaustible.

I love to write. I love to read what I write, I read what I write over and over, it’s a source of meditation: a record of me listening to myself in solitude. It’s not trite to say it’s a gift.

The great psychoanalyst Carl Rogers said that, when people came in for therapy, they came packing a facade behind which they were hiding all the assessments of worth they made of every person and being in their life, including themselves — and the repression was killing them.

The aggressive, violent American we see in the papers and online today — even those in public service — is hiding behind a façade that keeps breaking out into violence: sometimes with a gun; sometimes in denial of reality; sometimes with a flag pole — to which the American flag is attached — beating down on a neighbor the community hired to keep itself safe from flag-pole-beaters like themselves. Communitas non compos mentis.

Seven years before Nietzsche’s morals book came out, his overlooked “Daybreak” appeared in which he called for the “reevaluation of all values.”

He said, “I go into solitude so as not to drink out of everybody’s cistern. When I am among the many, I live as the many do, and I do not think as I really think; after a time it always seems as though they want to banish me from myself and rob me of my soul and I grow angry with everybody and fear everybody. I then require the desert, so as to grow good again.”

Where America is now: in the desert trying to find a way to grow good again.