When it comes to putting things down on paper, the Irish do it best

For Elizabeth Stack

As I was preparing to become an Irish citizen years ago, I started reading everything I could find on “Ireland,” not just in the 26 counties of the Republic but the six up north as well.

And to supplement my study, seven out of eight years I went to Ireland to see things for myself. As I sat in my grandmother’s house, drinking tea with a cousin, the aged Kerryman told me: The kitchen is an add-on; it’s where we used to tie the pony up.

When asked about my trips there, I said I was going not to see the country but to find out who the Irish were — a much more difficult task as anyone who’s been to Ireland with a keen nose knows.

And those wishing to take the approach I did, I urge: Learn how to listen (well); don’t ask direct personal questions — the Irish bat them away like pesky gnats — and keep in mind that the Irish listen with their eyes. So watch what they see.

As you might imagine, my study of Ireland brought me to “the potato” (práta in Irish) — not only its role during the “The Great Hunger,” as the Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh called the famine, but also how the Irish grow them: for centuries in “drills.” On the Internet an Irish farmer shows how: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zL_llRUxbz4

As you might imagine as well, the group I was (and am) most taken with are Ireland’s poets and writers. For centuries people have said that, when it comes to putting things down on paper, the Irish do it best. There’s an old expression: “The Irish have a way with words.”

Even the man on the street speaks in a kind of fancy prose. You might hear, “A widow and her money are soon courted” or, “Contentment is greater than a kingdom.” After their first trip to Ireland, travelers come back and say: I love the way those people talk — then try to imitate the lilt (unsuccessfully).

And, as anyone familiar with language knows, the Irish have a special relationship with the subjunctive — the mood of conditionality. I think it comes from being suppressed for so long.

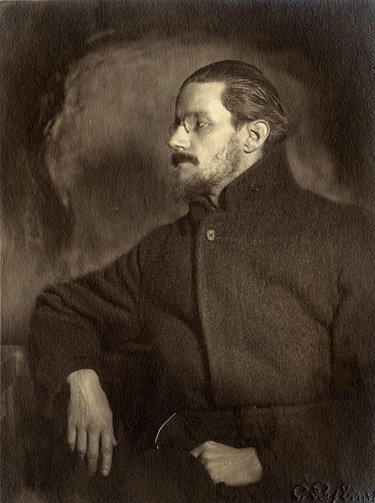

Those familiar with the Irish literary canon know well that this year, 2022, is the hundredth anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” It’s the Babe Ruth of books.

Whenever the best-of lists of “greatest stories ever told” come out, “Ulysses” is up there with “Don Quixote,” “War and Peace,” and other epics of that stature. Some Irish say they like “Ulysses” better than the Bible.

In retrospect, these many years later, it seems sad that, when “Ulysses” first came out, it was censored and confiscated like a piece of smut — and chief among the confiscators was not the Roman Catholic Church but the United States Post Office.

The book first appeared in 1918 in serialized form in The Little Review, an artistic, progressive magazine — Emma Goldman wrote for it — out of New York’s Greenwich Village. Its motto was: “Making No Compromise with the Public Taste.”

But a lady from Chicago took issue with that. She wrote a letter to the editor saying “Ulysses” was “Damnable, hellish filth from the gutter of a human mind born and bred in contamination.”

When the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice got involved, the publisher and editor of The Little Review were hauled into court.

The moral entrepreneurs were especially incensed by Chapter 13 — the famous “Nausicaa” episode — which depicts an encounter between a timid Dublin man, Leopold Bloom, and a beautiful Irish woman, Gerty MacDowell, who’s sitting on the beach of the Sandymount Strand in suburban Dublin. From afar, she’s staring into the eyes of a man whose eyes are penetrating hers.

The two never touch but the eye-exchange gets so hot that Gerty lifts her skirt to the top of the calf and Bloom explodes like a Roman candle.

At trial, Margaret Anderson, the publisher of The Little Review, and Jane Heap, the journal’s editor, were told to explain why the image of a man masturbating while a woman teases him with fantasy, should not be kept from public view. The women did of course but the court disagreed.

The Feb. 22, 1921 edition of The New York Times began its report on the outcome of the case with a four-tier headline: (1) IMPROPER NOVEL COSTS WOMEN $100; (2) Greenwich Village Publisher and Editor Fined for Producing “Ulysses.” (3) WOMAN’S DRESS DESCRIBED; (4) Prosecution, on Anti-Vice Society Complaint, Said Description Was Too Frank.

The original complainant for the case was the Vice Society’s Secretary, John Sumner; he must have preened all the way home that night, recalling the words of Judge James McInerney, one of the three justices on the bench, “I think that this novel is unintelligent and it seems to me like the work of a disordered mind.” “Disordered mind” in legal-speak means crazy.

Kevin Birmingham’s “The Most Dangerous Game: The Battle for James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses” touches on all these points, calling attention to the irony involved. He says that, while the book “was banned to protect the delicate sensibilities of female readers … [it] owes its existence to several women. It was inspired, in part, by one woman [Joyce’s wife, Nora Barnacle], funded by another [Harriet Shaw Weaver], serialized by two more [Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, joint editors of The Little Review] and published by yet another [Sylvia Beach].”

“Ulysses” ran into a problem with the censors in Britain as well so Joyce had to wait 10 years before Random House put the smut-sniffing dogs to sleep. The case was the United State of America v. One Book Entitled Ulysses by James Joyce. In his decision, Judge John M. Woolsey said while, “in many places the effect of Ulysses on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic, nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac.”

In 1948, the Catholic Church got involved in a similar case when Patrick Kavanagh’s “Tarry Flynn” came out, a touching account of rural life in 1930s Ireland. But the Éire Censorship Board declared the book “indecent and obscene,” implying that Tarry had followed Bloom’s lead.

Kavanagh kept saying the book was not about him but it is.

Years ago, I used to hear every St. Patrick’s Day there were, “only two kinds of people in the world, the Irish, and those who wish they were,” which seems so puerile now.

I also heard the Irish Blessing: “May good luck be with you Wherever you go, and your blessings outnumber the shamrocks that grow. May your days be many and your troubles be few, May all God's blessings descend upon you, May peace be within you, May your heart be strong, May you find what you’re seeking wherever you roam.”

Some say the prayer is sentimental but my concern is that it leaves out a blessing: May you go to your nearest library or bookstore and get a copy of Anthony Cronin’s “Dead as Doornails” containing prose as good as Joyce and poetry the equal of Yeats.

Cronin talks about how he met and interacted with and loved three Irish literary giants during 1940s and 1950s Dublin: Brendan Behan, Brian O’Nolan [aka Flann O’Brien aka Myles na Gopaleen], and Kavanagh — all of whom kept striving for self-esteem in a world where recognition was in short supply.

I might add that those three incarnations of Ireland’s literary soul died early from the drink — Behan at 41 — and that Cronin handles the weakness with understanding.

Today, March 17, 2022, I’d like to wish all our Enterprise readers a Happy St. Patrick’s Day and to those afflicted by these troubled times: Slàinte Mhaith.