Fantasy foxes teach lessons in racism and forgiveness

GUILDERLAND — Eric Airhienbuwa likes animals — all kinds: mammals, birds, even insects.

He likes extinct animals, too, namely dinosaurs.

And he has a special affinity for African elephants, a species at risk of extinction. “I just have an emotional connection with them because of how intelligent they are,” says Eric.

A junior at Guilderland High School, Eric plans to be a veterinarian, working as a writer on the side. He has recently published a book and has two more in mind.

His mother reports that, when Eric was younger, his father asked him, “Do you want to be a doctor?”

Eric recalled his reply was: “I want to be a vet.”

His mother gestures knee high, noting Eric was much younger, and says, when her husband asked why, Eric replied, “Because we have enough doctors for humans.”

Eric’s father is a doctor and both of his sisters are studying in the medical field. Jessica is studying molecular biology and biochemistry at the University at Albany while Leanne is studying biomedical engineering at Stony Brook University.

Eric said of his mother, “She’s always making sure I’m OK.”

When Eric was a freshman, his English teacher, Amy Salamone, had her students write every day. Eric wrote a Star Wars-inspired fantasy and liked it so much, he said, “I just kept going.”

“I didn’t want to get in trouble with Disney,” he said, so he changed the characters into animals.

He writes on a keyboard at his computer and incorporates his own experiences as well as things he sees on television or in movies into his writing, he said.

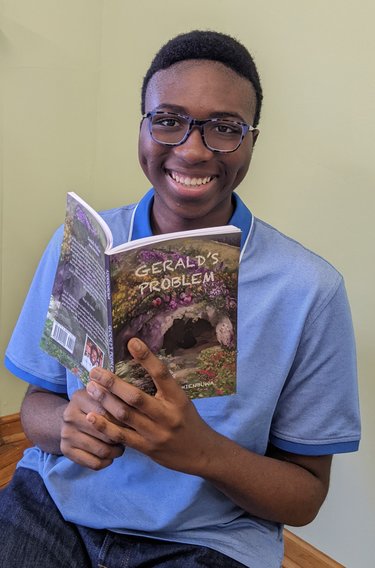

His book, “Gerald’s Problem,” is a fantasy-fueled and comedic adventure story about a fox named Gerald living in Yellowstone National Park.

When the story opens, Gerald’s best friend, a female wolf named Ink, has been killed by a rival pack of wolves. By the end of the story, Gerald himself is killed in a similar fashion but he has achieved his goal of revenge.

In between are many diverse animal characters, much lively dialogue, and magic blue berries that endow the eater with super powers.

Eric doesn’t outline a plot ahead of his writing a book. “This started out with a fox eating some berries … I worked it out as I went along … The more I wrote, the more the stories came along,” he said.

When he has an idea, Eric jots it onto Google Keep, a notes app on his phone. “I write randomly during school and then flesh it out when I get back home,” he said.

He chose to set his story in Yellowstone, Eric said, because although he has never been there he has read much about it and watched a number of documentaries filmed at the park.

Eric does a lot of research on his own and the scientific terms he uses in his book — such as lagomorph for a jackrabbit or passerine for a bluebird — do not come from a thesaurus but rather from his own studies. When asked about “passerine,” for example, Eric expands on the various characteristics like the arrangement of the bird’s toes, which allows for perching.

His book is populated with birds that inhabit Yellowstone.

Following in his sisters’ footsteps, Eric enjoyed working at the Farnsworth Middle School Butterfly Station where native plants are raised along with butterflies and visitors are given tours.

He is currently involved as a community scientist at the Pine Bush Preserve, tracking populations of buckmoths.

Eric for years has kept a journal, complete with sketches and descriptions of the various animals he has encountered. For example, he vividly remembers seeing a groundhog in his Guilderland backyard, not far from the pine bush, in 2021.

He loves to draw and took a full year of studio art in the ninth grade. This year, he is taking a class in cartooning because, he says, “My drawings are animated.”

He is also taking a screenwriting class with Andy Maycock who is himself a screenwriter. “We’re making a script of a feature film,” said Eric. “I’m writing about a bounty hunter trying to stop a cult, a magic witch cult.”

Although “Gerald’s Problem” is a fantasy, complete with talking animals and birds, the book also deals with real-life human problems.

The packs of wolves — the most evil pack is named Blood Fangs — sometime seem like gangs. And Gerald, despite the warning from a wise golden eagle, becomes addicted to the magic berries he imbibes.

Gerald’s mate, Flare, growls at Gerald and says, “I can’t believe you, Gerald! Why are you eating the very berries you told me were addictive? And in front of the kids, too!”

Flare and Gerald’s siblings hold an unsuccessful intervention where Sheldon, the crow who “helps animals in Yellowstone let go of their addictions,” declares, “I’m afraid that there is nothing I can do …. He is too far gone. He will probably die this month. Just make sure that he doesn’t do anything harmful.”

In real life, Eric is a member of the Black Student Union at Guilderland High School, of which his sister, Jessica, was a founder in 2020.

He serves as the group’s treasurer and enjoys the meetings because, he said, “We talk about issues around the world.”

Jessica Airhienbuwa spoke at the school’s first anti-hate rally in 2021 about microaggressions, small daily insults perpetrated against marginalized people.

She gave a long list of insults her family had suffered: a white patient assuming her physician father, wearing his lab coat, was a custodian; surprise that she doesn’t like watermelon; her sister being asked by a white teacher, “Do you ever wash your hair?”; advice to herself and her sister that they would look really pretty with straightened hair; being told she doesn’t act Black or that she speaks English really well.

“Microaggressions are cumulative and every unintended racist comment feels like a stinging paper cut,” said Jessica Airhienbuwa. “They are small … but over time, if you get enough unhealed paper cuts, you might just find yourself bleeding all over the place.”

She concluded, to applause, with a thought from her father on why white people in America don’t see the unequal treatment: “They … don’t see it because they don’t experience it.”

Asked if he had experienced similar small cuts, Eric said he had. “I usually just ignore them, like a mosquito buzzing around your face,” he said.

Eric pointed to a place in his book that deals with racism.

Flare, Gerald’s mate, had urged Gerald to get help from Alder, the wise golden eagle, but Gerald had been wary, convinced that an eagle would eat a fox.

After Alder instead helps him, Gerald asks the eagle, “Why didn’t you eat me?”

“I ate already,” the eagle replies. “Stop judging animals based on looks.”

The narrative goes on, “Gerald looked at the ground with chagrin and pawed at the ground.”

Asked about other life lessons readers might learn from his book, Eric said, “Maybe forgiveness. Because, in the end, it was Gerald’s arrogance and lust for revenge that got him killed.”

Eric wrote a quotation for one of Gerald’s siblings to speak after the death of their parents: “As my mother used to say, a seed must die in the ground to bring about new life.”

“I made that up myself,” said Eric.

****

“Gerald’s Problem,” a 138-page paperback, is available online through Dorrance Publishing Co. for $38 or at Barnes and Noble as a paperback for $38 or as an eBook for $33.