Students of color share hurts, demand change at Guilderland anti-hate rally

GUILDERLAND — Words ripped from the heart were spoken Friday afternoon beneath a banner that proclaimed “Our Unity is Our Strength.”

Guilderland High School students organized a two-hour anti-hate rally attended by a crowd of over 100 that included faculty, administrators, and school board members as well as students.

“Sick, that’s what I am. Congested by ill-will, hate, suffocating ….,” Savanna Jiang began her speech. “I am utterly sick of the stereotype I have to conform to just because of the shape of my eyes and the color of my skin.”

She went on, “I loathe myself for saying this but I do not want to be Asian.”

Jiang recounted hurts that went back to elementary school. She recounted recent hurts, too. “Why do your eyes look like that?” a girl asked her this year. She was sent three emojis — a dog, a cat, a bat — and asked if she was salivating yet.

A week ago, as her mother waited for Jiang at 8 p.m. outside of a friend's house, her mother texted Jiang to be on time. “It’s not safe for me to sit in a car outside,” her mother said.

“I feel unwelcome here,” said Jiang. “I feel alienated, I feel attacked, and I feel scared. My dad told me I was losing my Asian values, I was drifting away from my cultural identity.”

She said to applause, “We must demand change …. It begins right here.”

And then, quietly, Jiang ended where she had begun: “Sick is what I am. I’m tired. I’m the only one who catches this cold. I wish you would catch this cold. So you’d know how it feels to constantly have a stuffy nose.”

Maxine Alpart said that the term “Wasian” — which means white Asian — has been used many times to exclude her from both groups.

She learned to speak up for herself to be heard over the voices of others. She and Jiang first started organizing the rally, Alpart said, to provide a safe space for students to speak about their experiences with racism.

Holding on: Two of over 100 participants in an anti-hate rally at Guilderland High School on Friday form a long line with each person connected to the next by a ribbon. They stepped forward or backward in response to questions — forward, for example, if their name was always pronounced correctly and backward if they felt unwelcome in a public place.

In our culture, Alpart said, racism is brushed off as schoolyard teasing, which invalidates the experience.

“Students go to adults they trust and are pushed away with the idea they shouldn’t speak about their experiences because none will listen to them. We need to educate teachers on how to provide safe spaces for students before they get hurt.

“Our racism shouldn’t be your learning experience,”Alpart said, stressing that students need to initiate change.

She also said, “The student voice is strong and we will not be silenced anymore …. We all need to use our voices to lift each other up.”

Jeanine Cao said that the kind of racism she has experienced in Guilderland schools is not the kind of racism that you can report. “No one can get in trouble for simply being insensitive,” she said.

She remembered, at age 7, kids saying she wanted to eat their pets. “People still tell me not to eat their dog,” she said.

Cao also recalled a school bus ride in sixth grade where her eyes were mocked and her closest friend did nothing. Her parents told her to ignore people making fun of her. “But that also does nothing,” Cao said.

“I tried to stretch my eyes vertically,” she said. Cao said it took years for her to find peace with herself and she wants to prevent others from “the same fate of self-loathing.”

Since March 16, Cao said, referencing the mass shootings in Georgia where eight people were killed, six of whom were Asian women, she is afraid to let her parents leave the house by themselves.

When Cao shared her fears with teachers, she said, she was told they were irrational and that we live in a “good community.” Their comments only validated her fears, she said.

“Did they not realize I had had experiences in this community with bad people?” Cao asked.

White teachers will never truly understand her experiences, Cao said, calling for the school to hire people of color and saying, to applause, that 25 percent of the student population cannot be silenced.

According to the State Education Department, the Guilderland school district has 190 African-American students, or 4 percent; 181 Hispanic students, also 4 percent; 647 Asian students, or 13 percent; 3 Native American students, or 0 percent; 169 multi-racial students, or 4 percent; and 3,617 white students, or 75 percent.

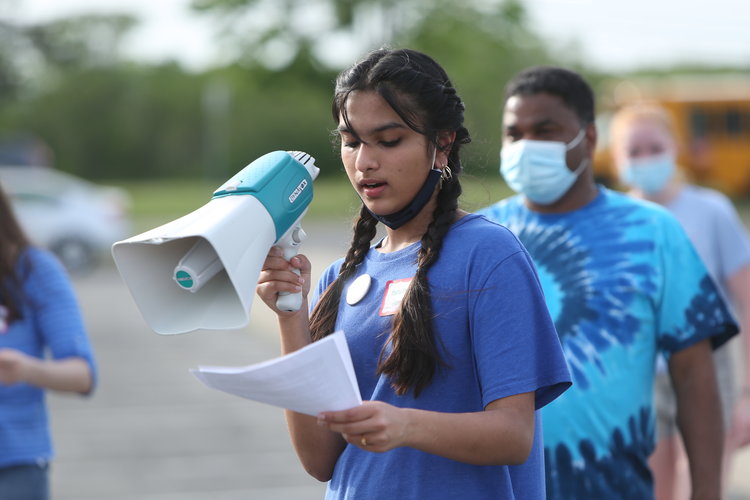

Through a bullhorn, Hanvitha Kunkalaguntla reads questions in an exercise where over 100 participants at an anti-hate rally stepped forward or backward in response.

Reasons for the rally

After the first round of highly charged speeches, student organizers handed out slips of paper, each with a symbol — one was the rainbow of gay pride — that onlookers were to share and discuss with each other.

Two of the student participants, who were also organizers of the event, were Athena Wu, a junior, and Abby Tyson, a sophomore. Together with their advisor, Matthew Pinchinat, a history teacher, they discussed with The Enterprise the reasons for the rally.

“In light of the recent surge of attacks, we wanted to do something about it,” said Wu. “This rally brought it all together.”

The event was jointly sponsored by the Black Student Union, the high school’s student government, the Anti-Racism Committee, and Students and Teachers Against Racism known as STAR. The rally culminated a week of events, including Heritage Days, Unity Days, and Hands Across Guilderland.

After decades of incidents of racial discrimination in Guilderland schools — several of which came to public notice when lawsuits were filed — school board members at their July 1 meeting were passionate about pursuing changes in curriculum, policy, and staff training and recruitment.

Shortly after George Floyd’s May 25 murder last year, a Guilderland High School alumna sent an email to the superintendent and the school board, saying that Guilderland needed a comprehensive plan to address racism in its system.

A conversation followed in which a half-dozen Guilderland graduates, all of them Black women, talked about the racism they had experienced while students in the district. The women expressed their anger and frustration over the school’s curriculum. Subsequently the school board appointed an anti-racism committee. The school board, in a split vote last month, included in next year’s budget a full-time administrator to focus on equity, diversity, and inclusion.

“I hope they don’t stop there,” said Wu, stating that hiring the new administrator should be a starting point, not an end point.

“I’m extremely proud of how the Guilderland community is handling this,” said Tyson.

“What matters most is what the students think and feel. Therefore, it is essential to me,” said Pinchinat.

“A lot of people of color are afraid of talking about this,” said Wu, urging people to educate themselves by talking to people who come from different cultures.

Tyson agreed that listening is important. “This is a beginning,” Wu stressed again and Tyson added that the movement needs to encompass the entire community, not just the school community.

“We need to listen to our students and believe their stories,” said Pinchinat. “We need to recognize they are the experts.”

“Microaggressions are cumulative and every unintended racist comment feels like a stinging paper cut,” says Jessica Airhienbuwa. “They are small … but over time, if you get enough unhealed paper cuts, you might just find yourself bleeding all over the place.”

“What are we afraid of?”

More heartfelt speeches followed the symbols activity as Jessica Airhienbuwa, a Black woman, eloquently defined microaggressions, small daily insults perpetrated against marginalized people.

She began her speech, telling how, after her father, rather than her mother, for once took her to a driving lesson, the instructor told her, “It’s good to know that people like you have two parents involved. That’s usually not the case.”

She thought about the hurtful comment throughout the lesson and “came to the bitter realization that he had assumed, because I was Black, my parents were no longer together.”

Airhienbuwa proceeded with a long list of similar insults: a white patient assuming her her physician father, wearing his lab coat, was a custodian; surprise that she doesn’t like watermelon; her sister being asked by a white teacher, “Do you ever wash your hair?”; advice to herself and her sister that they would look really pretty with straightened hair; being told she doesn’t act Black or that she speaks English really well.

“Microaggressions are cumulative and every unintended racist comment feels like a stinging paper cut,” said Airhienbuwa. “They are small … but over time, if you get enough unhealed paper cuts, you might just find yourself bleeding all over the place.”

Going into the sixth grade, Airhienbuwa said, she tried to change her personality. “I thought there was something wrong with me ….,” she said. “I had to learn at an early age that we are not all treated the same.”

She concluded, to applause, with a thought from her father on why white people in America don’t see the unequal treatment: “They … don’t see it because they don’t experience it.”

Pinchinat, the history teacher and advisor, spoke next about his gratitude for his family. His parents were born in Haiti, children of another land, he said.

“I’m a Christian,” Pinchinat said, but specified he was “not the hateful, judgmental, bigoted” type. His parents had taught him to be kind and good, he said.

“I never wear a do-rag out in public for fear of being branded a thug,” Pinchinat said. He also said he resents the feeling that he has to represent an entire race.

“I love being a teacher. God, I love being a teacher …,” he said. I want to carry on my father’s legacy. I could speak for hours yet still feel that not enough has been said, wondering still was my voice even heard.”

“What are we afraid of?” asked Meghana Bhupati, a Guilderland junior.

Although the word “respect” was plastered all over the elementary-school walls, she said, “Treating people kindly is not respect.”

She went on, “We need to separate race and personality, race and intelligence, race and beauty.” Lack of respect, she said, perpetuates a hierarchy.

“Our society prioritizes what is on the surface rather than the person underneath,”said Bhupati.

She also asked, “Isn’t our mission, as Martin Luther King said, to judge people … not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character?”

She urged the crowd, “Step in if you see someone being invalidated.”

Bhupati concluded, “Unity here doesn’t mean we see eye to eye …. The goal is that one day we will be united in celebrating our differences.”

Take a step

The onlookers, who were seated in socially-distanced metal folding chairs, facing the school, were then asked to form a long line in the parking lot. Each person held one end of a ribbon, which in turn was held by the person next in the line.

Students with bullhorns read from scripts asking the hundred or so people in line to take a step or two forward or backward in answer to questions.

They were to step forward if their name was always pronounced correctly, or if they never heard jokes about their race or gender, or if they had representative children’s toys growing up, or if they could find their skin tone in make-up products.

Largely white people had stepped forward.

They were to step backward if they had been harassed or disrespected by police, or if they had felt unwelcome in a public place, or if security guards had followed them in a store because of their racial identity.

Largely people of color stepped backwards.

When the crowd members had returned to their seats, the student organizers asked if any had felt uncomfortable to be at the back of the line or to be at the front of the line.

“Turn to a partner and explain how that made you feel specifically,” they were told.

David Zhang and Sameeha Hasan then led the crowd in a pledge to “condemn hate and bigotry in our community” and to “strive to create a more inclusive school, one that isn’t afraid to stand up for others and to acknowledge its faults.”

The pledge ended, “Our journey towards celebrating diversity and educating ourselves on discrimination begins now.”

Leaders from student government and the Black Student Union then gave presentations, sharing important parts of Black history and reinforcing messages on microaggression and the need not to be defeated by hate.

The crowd was urged to advocate on social media and to become lobbyists, particularly for the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act currently before Congress.

Finally, Terrance Hayes’s poem, “George Floyd,” was read by Abby Tyson: “...there will be/ no stormy weather on the water/ bored to death any means of killing/time is on your side of the bed/of the truck transporting Emmett/till the break of day Emmett till/the river runs dry your face/the music of the spheres/Emmett till the end of time”

The rally closed with nine minutes and 29 seconds — the length of time former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, now a convicted murderer, kept his knee on the neck of Floyd as he cried out, “I can’t breathe” — of quiet.

Pinchinat urged those in the crowd to take notes on their phones as he provided prompts — on the reaction to Hayes’s poem, on the past year and a half of “unprecedented solitude,” on what it means to be “surrounded by your thoughts but unable to use your voice.”