Plumbing the past blazes the way to a richer, more distinctive future

An individual can make a difference.

That is important to remember when we live in an era when many of us are known as numbers — from our Social Security numbers to our license-plate numbers — and the built landscape of America is beginning to have a disconcerting sameness.

The big-box stores on the outskirts of Albany look a lot like the big-box stores on the outskirts of Seattle. A McDonald’s burger in New York tastes the same as one in Minneapolis or in San Francisco. What distinguishes one place from another? What makes each one of us unique as an individual?

Part of the answer lies in history.

We were heartened to have recently published the stories of two individuals in the town of New Scotland who are making a difference with work that, in the long run, could shape the entire community, helping it to retain its unique identity. And we believe their work can inspire individuals in other communities, too.

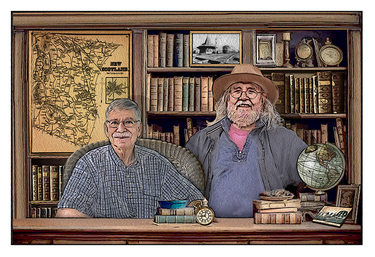

Dennis Sullivan and Alan Kowlowitz last month were each given the Arthur Pound Award by the New Scotland Historical Society.

History matters. The stories we tell ourselves about our nation or our town can define who we are — as a people and as individuals. As journalists at The Enterprise, we are authors of the first draft of local history.

But what gets remembered, plucked out later, selected over time, to create a narrative of who we are?

“Our sense of self is not tied solely to personally experienced events. Who we are and how we understand our personal experiences is also shaped by how we understand other’s experiences ….,” write psychologists Robyn Fivush, Jennifer G. Bohanek, and Marshall Duke.

“Stories of the past we did not experience still provide powerful models, frameworks, and perspectives for understanding our own experiences,” the psychologists write. “We construct a sense of self through time that relies both on an evaluative perspective of our own personal history, as well as how our history fits into larger cultural and historical frameworks.”

Sullivan is the village historian and, in that role, has created an historical framework for Voorheesville and for the individuals who live there.

Over a century ago, New York state was the first in the nation to adopt a law mandating that a historian be appointed for every municipality. New York is still the only state with such a requirement, and currently has over 1,600 historians across the state.

Local historians are given a lot of latitude by the state in how they want to do their jobs. We’ve written on this page before about the importance of the work done by municipal historians — an unfunded state mandate — and advocated for support.

But what we’d like to focus on today is how the work of one village historian is leading to preservation.

Sullivan, an Enterprise columnist, has been many things in his long life — a monk, a teacher, a classicist, an editor, an academic, a poet, an advocate for restorative justice, a gardener; the list goes on.

But, at his heart, we believe Sullivan is a storyteller.

His stories, often based on copious research, ring true with a sometimes radical perspective. He has just published a new book, “Veni, Vidi, Trucidavi: Caesar The Killer,” that upends the traditional view of Caesar. Sullivan’s narrative is about a man who destroyed nations so that he might be king.

The stories we tell ourselves — whether about ancient civilizations that shaped our modern society or about the relatively recent 250-year history of our nation — define who we are and they can shape the places where we live.

Sullivan wrote an in-depth series on the Bender Melon Farm in New Scotland that helped lead to the farmland being preserved in the heart of a now-suburban town.

He then spent three years researching the history of Voorheesville and how it grew as a railroad town. He told that story in his engaging book, “Voorheesville, New York: A Sketch of the Beginnings of a Nineteenth-Century Railroad Town.”

Alan Kowlowitz called Sullivan’s contribution “huge” in leading to Voorheesville being considered for designation as a national historic district.

“It told the story in a very accessible way for the citizens here,” said Kowlowitz. Voorheesville, he said, has embraced its identity as a railroad village.

“Once being a commercial railroad town is palpable and it opens up your eyes when you walk down Main Street …,” said Kowlowitz. “And, of course, we still have the railroad going through.”

Kowlowitz himself was raised in Queens — the son of a fur worker and dental secretary — whose best subject was always history.

Throughout his life, he has been a constant reader of history. He prefers academic work over popular history books, in which the errors rankle him.

For their honeymoon, he and his wife visited historic Williamsburg and Monticello.

As newcomers move to Voorheesville and New Scotland, Kowlowitz hopes they will embrace their heritage, not as a matter of genetics, a love of place handed down through family, but rather like the love that ties a marriage together.

He cites a tour of Voorheesville given by Dennis Ulion, focusing on the community of Italian immigrants that settled in Voorheesville several generations ago — their history now intertwined with the village’s.

For decades on this page, we have called for the towns and villages we cover to document their historic buildings to catalog their built history, which distinguishes them from every other place on Earth.

Kowlowitz has spearheaded a movement to do just that. He chairs the joint village and town Historic Preservation Commission. Voorheesville and New Scotland were awarded a grant from the Preservation League of New York State to fund a cultural resource survey.

“You can’t preserve what you don’t know,” Kowlowitz told us in 2021 in anticipation of the survey.

The original plan was to survey the village of Voorheesville and the hamlets of New Salem and New Scotland. We had lived in New Salem, restoring a house built, in part, in the late 1700s, with floor planks three feet wide underfoot and massive hand-hewn beams overhead.

One of the things we loved about the hamlet, clustered around a Dutch Reformed Church at the foot of the Helderbergs, was the evolution of architecture it displayed: Greek Revival, Carpenter Gothic, Victorian.

So we were disappointed when we caught up with Kowlowitz this spring to learn that the two hamlets hadn’t passed muster with the experts, who found they “lack the integrity” needed to create an historic district.

When you hire experts, Kowlowitz said, sometimes they tell you what you don’t want to hear.

“It’s almost like a Catch-22,” he said. Kowlowitz explained if, say, New Salem were to be made a national historic district, there would be an opportunity for grants and tax breaks that would foster historic preservation. But, because it is deemed not historic enough, that restoration won’t occur.

“New Salem has a story but it’s not been told,” Kowlowitz said, contrasting it with Voorheesville, which had Sullivan to research and tell its story.

Which brings us back to the value of storytelling for establishing a sense of place, of who we are.

In addition to Voorheesville, the experts chose two other places in New Scotland for potential designation as national historic districts: Tarrytown and Indian Ladder Farms.

The report by Hartgen Archeological Associates says that the transformation of the town from an agricultural area to mature communities after the arrival of the railroad in 1863 is recorded in the built culture of the village of Voorheesville, the hamlet of Tarrytown, and Indian Ladder Farms.

“The Mahicans formerly owned the lands currently known as Onesquethaw and the Hamlet of Tarrytown before it was lost to the Mohawks during the Beaver Wars in 1628,” the report says. In 1685, Teunis Slingerland, a trader from Beverwyck, now Albany, and his son-in-law, Johannes Appel, purchased the Onisquotha Patent, a 300-acre tract north of the Coeymans Patent.

Throughout the Revolutionary War, the report notes, the Onesquethaw Valley was a hotbed of Tory sympathy. It also says that the Onesquethaw Creek was important in the colonial era because it produced valuable farmland as well as a strategic trade route between the Hudson River and the Native Americans living in the Mohawk Valley.

Tarrytown, said Kowlowitz, represents a farming community from the early 19th Century. “The structures there have coherence,” he said, citing the several farmhouses and a church all built of limestone. He cited other places with historic limestone buildings that draw tourists.

Similarly, Kowlowitz said, consistency is the key to Indian Ladder Farms being chosen as a potential national district with its shingled buildings from the early 20th Century.

Kowlowitz said the next steps are to educate the public about the value of these three potential national historic districts and also teach about what a historic district means.

“People have a false impression that it restricts what people can do on private property,” he said. “That is not the case.”

He wants to make people aware of the advantages like grants and tax breaks.

“I’m interested in history,” said Kowlowitz, who worked for the New York State Archives, “but I think historic preservation should also support other things that a community wants to accomplish.”

He believes historic preservation can improve quality of life and help economic and community development.

“Tying historic preservation to those things makes it an inviting thing for people that maybe just have a slight interest in history or no interest in history, but can see how it can help a community’s sense of self and place and actually materially help our community.”

Kowlowitz hopes to bring together many facets of the community — government, business leaders, community organizations, educators, people with legal or engineering expertise — to undertake the arduous task of applying for national historic districts.

This effort must include not just residents whose families have lived in town for generations but newcomers who are making New Scotland the fastest growing town in the county.

“To be successful,” said Kowlowitz, “you need to have the newcomers embrace the history and see it as their history and a continuing history.”

As nearby Guilderland updates its comprehensive land-use plan, we urge the committee working on the update to prioritize a catalog of the remaining historic structures in town before it entirely becomes a suburban sprawl much like many other places. This would help preserve Guilderland’s identity and give the individuals living in town a cultural and historical framework.

Residents of McKownville took it upon themselves to achieve an historic-district designation; not coincidentally, theirs is a part of town that has a strong sense of community and a unique identity. The same is true of the village of Altamont.

Meanwhile, we commend Sullivan for telling the story of Voorheesville and Kowlowitz for working tirelessly to bring the community along in recognizing the worth of history. Like Kowlowitz, we believe if the different facets of New Scotland came together, they could raise both pride and prosperity in their community.