Kowlowitz hopes New Scotlanders will come together, raising pride and prosperity, as they apply for national historic districts

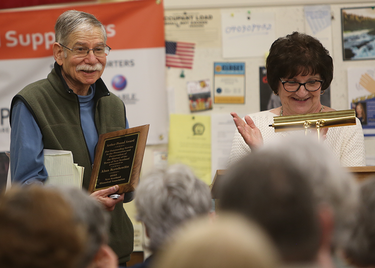

The Enterprise — Michael Koff

Alan Kolowitz accepts the Arthur Pound Award, presented Tuesday by Sarita Winchell, president of the New Scotland Historical Association. Established Nov. 7, 1989, the award is given from time to time to recognize someone who has helped promote and preserve the history of New Scotland in an extraordinary way.

NEW SCOTLAND — By looking to its past, New Scotland may build a brighter future, Alan Kowlowitz believes.

Kowlowitz chairs the joint village and town Historic Preservation Commission. In 2021, Voorheesville and New Scotland were awarded a $10,000 grant from the Preservation League of New York State to fund a cultural resource survey.

The survey cost $17,400 and, in addition to the $10,000 grant, the New Scotland Historical Association, the village of Voorheesville, and the town of New Scotland each donated $2,000, Kowlowitz said; the remaining $1,400 was secured from the Voorheesville Community and School Foundation.

The survey by Hartgen Archeological Associates is now complete and posted on The Altamont Enterprise website.

Kowlowitz has made presentations to both the town and village boards and spoke at length about the survey in this week’s Enterprise podcast.

Walter Wheeler, an architectural historian at Hartgen, described his work as a “reconnaissance” survey, which Kowlowitz said is “a broad overview of the community to find out what was there and what may qualify for the national historic register.”

The report explains that the national register has four criteria for significance:

— Association with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of history;

— Association with the lives of persons significant in the past;

— Embodying the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction; or

— Potentially yielding information important to history.

“The criteria are very stringent,” said Kowlowitz. “And that may explain why the results were not exactly what we expected and the survey had to be refocused.”

The original plan, after the cost of surveying the entire town was determined to be prohibitive, was to survey the village of Voorheesville and the hamlets of New Scotland and New Saleem.

Kowlowitz called it “a disappointment” that buildings in the two hamlets were found to, as the report put it, “lack the integrity” needed to create an historic district.

“A lot of the structures had been modified — the vinyl and tin man had been through town and that is … a killer as far as the historic character,” he said.

When you hire experts, Kowlowitz said, sometimes they tell you what you don’t want to hear.

“It’s almost like a Catch-22,” he said. He explained if, say, New Salem were to be made a national historic district, there would be an opportunity for grants and tax breaks that would foster historic preservation. But, because it is deemed not historic enough, that restoration won’t occur.

“New Salem has a story but it’s not been told,” Kowlowitz said, contrasting it with Voorheesville.

Dennis Sullivan, the village historian, wrote an engaging and carefully researched book, “Voorheesville, New York – A Sketch of the Beginnings of a Nineteenth Century Railroad Town,” that Kowlowitz called “huge.”

“It told the story in a very accessible way for the citizens here,” said Kowlowitz. Voorheesville, he said, has embraced its identity as a railroad village.

“Once being a commercial railroad town is palpable and it opens up your eyes when you walk down Main Street …,” said Kowlowitz. “And, of course, we still have the railroad going through.”

Kowlowitz also spoke of the attraction of the Albany County Helderberg-Hudson Rail Trail, which starts in Voorheesville and travels over nine miles into Albany.

The Hartgen report says 10 resources in the proposed Voorheesville district were determined to be individually eligible for listing on the National Register.

“Three resources within the proposed Voorheesville Historic District (40, 42 and 43 South Main Street), were demolished during the course of the past year; they have been left in the survey but are not included in the final count of resources in the proposed historic district,” the report says. “Thus, the district as proposed consists of 110 resources, 13 of which do not contribute to the district.”

The South Main Street buildings — two of them were Victorian — were torn down to make way for a new restaurant, café, and parking lot being built by Business for Good in the heart of Voorheesville.

Kowlowitz believes that, with research, someone could write a compelling story about New Salem, a much older settlement than Victorian Voorheesville, and hopes to advocate for local historic districts as well.

Even a local historic district, he said, “can help the community see itself in a new light and bring something positive to a community.”

Making a failed attempt for a national register bid generally dooms the potential of a historic district for good, Kowlowitz said he was told.

After Hartgen rejected the hamlets of New Salem and New Scotland, Chris Albright, whom Kowlowitz said has an encyclopedic knowledge of his native New Scotland, took Wheeler on a tour to see what other areas might have the potential to become national historic districts.

Ultimately, two other potential districts were chosen: Tarrytown and Indian Ladder Farms.

The Hartgen report says that the transformation of the town from an agricultural area to mature communities after the arrival of the railroad in 1863 is recorded in the built culture of the village of Voorheesville, the hamlet of Tarrytown, and Indian Ladder Farms.

“The Mahicans formerly owned the lands currently known as Onesquethaw and the Hamlet of Tarrytown before it was lost to the Mohawks during the Beaver Wars in 1628,” the report says. In 1685, Teunis Slingerland, a trader from Beverwyck, now Albany, and his son-in-law, Johannes Appel, purchased the Onisquotha Patent, a 300-acre tract north of the Coeymans Patent.

Throughout the Revolutionary War, the report notes, the Onesquethaw Valley was a hotbed of Tory sympathy. It also says that the Onesquethaw Creek was important in the colonial era because it produced valuable farmland as well as a strategic trade route between the Hudson River and the Native Americans living in the Mohawk Valley.

Tarrytown, said Kowlowitz, represents a farming community from the early 19th Century. “The structures there have coherence,” he said, citing the several farmhouses and a church all built of limestone. He cited other places with historic limestone buildings that draw tourists.

Similarly, Kowlowitz said, consistency is the key to Indian Ladder Farms being chosen as a potential national district with its shingled buildings from the early 20th Century.

He cited the “active agricultural fields,” which have become rare in Albany County, and the views of the Helderbergs.

The Hartgen report notes that Indian Ladder Farms originated in 1915 when Peter Gansevoort Ten Eyck purchased five farms below the Helderberg escarpment and combined them; he was a state commissioner of agriculture as well as a congressman.

Indian Ladder Farms started as a dairy and, when the dairy barn burned in 1949, Peter G. Ten Eyck, the son of the farm’s founder, raised beef cattle and planted apple and pear trees. Peter G. Ten Eyck II, the third generation of the family to live on the property, opened a farm store. His children, Laura Ten Eyck and Peter G. Ten Eyck III, are the fourth generation of the family to run the farm, which has become a major tourist attraction with Laura Ten Eyck’s husband, Dietrich Gehring, opening a brewery.

Indian Ladder Farms received nearly $900,000 in 2003 to keep 317 acres undeveloped — about a quarter of that money had to be raised from the community for the farm to get $628,670 from the state’s Clean Air/Clean Water Bond Act.

Kowlowitz said the next steps are to educate the public about the value of these three potential national historic districts and also teach about what a historic district means.

“People have a false impression that it restricts what people can do on private property,” he said. “That is not the case.”

He wants to make people aware of the advantages like grants and tax breaks.

“I’m interested in history,” said Kowlowitz, who worked for the New York State Archives, “but I think historic preservation should also support other things that a community wants to accomplish.”

He believes historic preservation can improve quality of life and help economic and community development.

“Tying historic preservation to those things makes it an inviting thing for people that maybe just have a slight interest in history or no interest in history, but can see how it can help a community’s sense of self and place and actually materially help our community.”

Kowlowitz hopes to bring together many facets of the community — government, business leaders, community organizations, educators, people with legal or engineering expertise — to undertake the arduous task of applying for national historic districts.

This effort must include not just residents whose families have lived in town for generations but newcomers who are making New Scotland the fastest growing town in the county.

“To be successful,” said Kowlowitz, “you need to have the newcomers embrace the history and see it as their history and a continuing history.”