BKW appoints impartial hearing officer over due-process complaint

HILLTOWNS — The Berne-Knox-Westerlo School Board appointed an impartial hearing officer at an afternoon special meeting last week after receiving a due-process complaint from a parent or parents, putting into focus a somewhat obscure but useful mechanism for those who are involved in securing the interests of a student with any kind of disability that impacts learning.

The details of the situation in question at BKW are unknown at this time as Superintendent Timothy Mundell could not be reached, and the district’s policy is to keep “all issues relating to a request for and conduct of an impartial hearing” confidential.

However, all due-process complaints center around the identification of students with disabilities and their placement in special-education settings. Parents, guardians, and public agencies are authorized to file such complaints by the New York State Education Department.

Once a district receives a due-process complaint, it must formulate a written notice (if it hasn’t done so prior to the complaint) that lays out its reasoning for its behavior, whether it had proposed an action that a filer disagreed with or failed to take action that a filer had proposed.

It also must begin the process of selecting an impartial hearing officer listed by the education department, which trains and certifies those officers. In BKW’s case, the officer is Robert Greenwood, who could not be reached.

During hearings, the filer(s) and school district hash out facts related to the case with assistance from the hearing officer, who ultimately makes a decision that is legally binding. However, anyone unhappy with the outcome has the option to appeal.

The impartial hearing officer also has the authority to determine that the parent or agency representing a student does not have that student’s best interests in mind and subsequently appoint a guardian ad litem, or a temporary replacement.

Due process hearings are rare. The Guilderland School District, which has more than five times BKW’s enrollment with just under 5,000 students, has had only a handful of due process complaints over the past two decades — a figure based on Enterprise coverage during that time.

Part of the reason may be that all schools are required to participate in a less formal mediation process over issues connected to special education should any parent wish to initiate that.

The appearance and outcome of a mediation is similar to a due-process hearing in that there is a third party present to guide the proceedings. If an agreement is reached by all parties, it is formalized in a legally binding written agreement. The mediator in these cases is selected from a private conflict resolution agency and cannot be associated with the school or state education department.

New York State law holds that mediation is not a requirement to file a due-process complaint and that pursuing mediation does not preclude a parent or agency from pursuing a due-process hearing; however, information disclosed during mediation cannot be used in a due-process hearing.

BKW’s special-education plan

Like all districts in the state, BKW has a special-education plan that must be updated every two years. BKW’s plan was last updated in time for the 2020-21 school year.

Under state law, BKW is obligated to identify all students who have a learning disability within the district, whether or not they actually attend classes at BKW (unless they attend a private school). A disability is defined as any handicap to learning — whether it be cognitive, like dyslexia; physical, like blindness; or emotional — that makes a traditional educational setting insufficient for that student.

According to the district’s special-education plan, there were 117 students within the district identified as having a disability, with 20 of those students receiving services out-of-district.

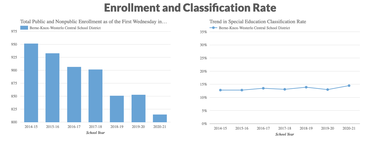

According to the state’s education department, BKW in 2020 had 716 students, meaning about 16 percent have special needs.

The plan states that students are referred to the district’s committee on special education when a student is neither meeting nor making adequate progress toward grade-level proficiency in math or reading, and when prereferral interventions are unsuccessful.

If the committee determines that a student has a disability, it then begins developing an individualized education program, or IEP, that incorporates a wide range of information, such as the nature of the disability, what areas of learning it impacts, what hardware might be needed to support the student, learning objectives, and more.

It also determines the student’s “least restrictive environment,” or LRE, which the district is obligated to provide, according to the plan. The idea behind LRE is that students should have maximum access to typical learning environments as often as can be managed to prevent isolation and/or loss of learning, according to Understood, a foundation that advocates for students with disabilities.

To this end, BKW offers what it calls integrated co-teaching classes, according to the plan, wherein two teachers — one who is trained in general education and another who is trained in special education — work together within the same classroom, which is made up of students with and without disabilities.

For the 2020-21 school year, BKW had 25 staff members who provided services to students with disabilities. The majority — 13 — are special-education teachers within the primary and secondary schools, while the rest provide ancillary services, such as counseling and things like physical and speech therapy.

In 2019, The Enterprise reported that BKW students with disabilities scored in the lowest 10 percent in their group for English, math, and science, and that the district was a potential target school for state intervention.

The state education department’s most recent special education data profile for BKW shows the school in good standing, using data from the 2019-2020 school year. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the usual performance and reporting standards so, although more recent data exists, the New York State Education Department warns that the more recent data is not representative and the department did not use it for its report cards.

The graduation rate for students with disabilities at BKW was 78.6 percent, which is above the state target of 71 percent. The dropout rate was 7.1 percent, which is below the state target of 19.37 percent.

The district did not meet the participation target rates for any of the state assessments reported — sometimes just barely, and sometimes significantly. The state’s target for all assessments is 95 percent.

The lowest participation rate among learning disabled students at BKW was for high school English Language Arts, at 11.11 percent. That number appears to be an outlier, though, as generally the participation rates were in the 50s or 80s. The highest were for fourth-grade English and fourth-grade math, at 88.89 percent each. The average of all the rates is 64.55 percent.

The students met state targets for proficiency on all tests except for fourth-grade math, which had a target rate of 18.14 percent. The exact figures for each assessment can be seen online at the New York State Education Department website under the Berne-Knox-Westerlo Central School District special education data profile for 2020-21.

BKW did not meet the target proficiency gap rate for eighth-grade English — with the district’s rate being 39.58 percent against the state target of 33.94 percent — or fourth-grade math, which was 51.28 percent against the state’s 31.25 percent.

Misidentification of learning disabilities

Although it seems at first blush that a learning disability would make itself obvious in a classroom, identifying disabilities can be complicated, and they’re sometimes missed or miscategorized.

Socioeconomic factors play a big role in this, as students of color and those whose families are poor can be over- or underidentified depending on their context.

The organization Education Week points to a series of largely state-specific studies from 2019 that collectively found that, while students who are Black and Hispanic were overall more likely to be identified as learning disabled, that was less likely to be the case in school districts with student populations that were at least 90 percent non-white, where they were more likely to be under-identified.

White students in the majority-minority districts were also more likely to be diagnosed with a learning disability.

“The lines between what is a disability and what is not is fuzzy, and they are dependent in part on our social context,” researcher Rachel E. Fish was quoted as saying.

(BKW, according to 2020 figures from the state’s education department, is overwhelmingly white: five students, or 1 percent, are Black; 18 students, or 3 percent, are Hispanic; four students, or 1 percent, are Asian; 15 students, or 2 percent, are multiracial; and 673 students, or 94 percent, are white.)

Further complicating identification of learning disabilities is the fact that some students who are learning disabled simply don’t show up that way in standardized test scores, either because their impairment is relatively mild or because their non-impaired areas of ability are strong enough to obscure their disability.

A New Yorker article from 2015 focuses on the existence of “stealth dyslexia,” or dyslexia that’s overcome by a student who, against expectations, manages to become a “superior reader” for reasons that appear to be unrelated to overall intelligence.

But intelligence also interacts with learning disabled outcomes, as evidenced by what are known as twice-exceptional learners — those who are both gifted and learning disabled. These kids can be identified as one or the other, or neither, all of which can lead to problems, according to the Child Mind Institute.

“Once 2e kids are identified, it can still be difficult to get the support these children need in school,” their article states. “If they’re in a gifted program, they may be floundering in a certain area. If they’re placed in a special-ed program, it may not challenge them, and they may be frustrated and restless. In either case, anxiety, depression, a lack of self-esteem and emotional dysregulation can result, leading to behavior problems.”

Overall, it’s believed that 20 percent of students have some form of learning disability, and that nearly 12 percent of them go undiagnosed, according to the Learning Disabilities Association of America, and the consequences can be dire.

The National Center for Learning Disabilities reports that students with learning disabilities are three times as likely to drop out of school, and that a third of the United States prison population qualify as having a learning disability, putting them above the common average and indicating at least an indirect relationship between the two.