Water woes present challenge for 41-lot subdivision proposed off of Gun Club Road

GUILDERLAND — A housing project in the very early stages of planning is already running into issues with its neighbors and with its water supply.

The developer, Prime Capital Development, doesn’t have an easy way to get water to the 41 proposed lots off of Gun Club Road and neighbors say current drainage problems would be exacerbated with new homes.

The proposed cluster subdivision was presented to the Guilderland Development Planning Committee on Feb. 16.

The committee meetings, town planner Kenneth Kovalchik explained, are a first chance for various department staff to provide developers with feedback before any formal steps are taken.

“So I just wanted to reiterate that the application we received this morning is just for the Development Planning Committee,” Kovalchik said. “It is not a formal application that has been submitted to the planning board yet.”

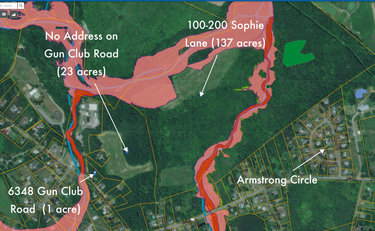

The would-be development is located on 159 acres largely off of Route 146 but is mostly accessible from Gun Club Road. Thirty-seven of the homes would be accessed from Gun Club Road, between 6330 Gun Club Road and the property of the former Crounse House, and between 6338 Gun Club and 6370 Gun Club, the home of Altamont’s sewage treatment plant.

The remaining four homes would be accessed from Armstrong Drive, which would see a now-dead end between 19 and 21 Armstrong turned into a four-home cul-de-sac.

Water

Kovalchik said there would be an issue supplying water to the development.

There’s a proposal to lay a new over-mile-long line from the intersection of routes 158 and 146 to Armstrong Drive — where a village of Altamont water line currently terminates.

Joe Bianchine of ABD Engineers said Altamont was initially “interested in providing water to us,” but ultimately the village didn’t have sufficient additional supply, he said.

Bianchine said the developer, Prime Capital Development, went back to the waterline alternative and is looking for other ways to offset costs, and said Altamont is looking into grants.

Altamont has looked to set up an emergency interconnection with Guilderland in the past, and is very aware of the costs and issues associated with trying to tie in to town water.

In May 2018, village trustees were notified just weeks before an application deadline of grants that would have funded between 40 and 60 percent of the $900,000 needed to install the emergency interconnection with the town. The board balked at committing the village to a project with a high upfront cost on such short notice — Altamont would have had to pay the entire $900,000 for the project and then ask the state for reimbursement.

The village was made aware by its engineer at the time, having paid $23,300 for the privilege, what it would have taken to get Guilderland’s water from the intersection of routes 146 and 158 to Armstrong Drive: $600,000 for the waterline and $300,000 for the pump station. The village ultimately applied for but did not receive any of the state’s nearly $324 million in 2018 Water Infrastructure Improvement Grants.

An Altamont interconnection with Guilderland had been a topic of discussion as recently as April 2021, when Mayor Kerry Dineen acknowledged it was “still a want and a need for the Village,” according to meeting minutes, but said the project had been shelved due to lack of funds.

Kovalchik, during the Feb. 16 committee meeting, noted the topography of Route 146 and asked Bianchine if there’d be a need for a pump station. Bianchine didn’t think the elevation in the road coupled with tying into the Altamont water supply would necessitate a pump station.

Guilderland Superintendent of Water and Wastewater Management Timothy McIntyre did not share Bianchine’s optimistic view.

“This is a big animal you’re talking about here; we extended the west end water out to where it is now, on Weaver Road and Phillips Hardware area, many bunch of years ago,” McIntyre said. “To make a long story short, it went as far as it could go based on elevation, where we’re required to sufficiently supply pounds [of pressure] to certain areas. That’s why it stopped where it is. And we would not be able to facilitate pressure past that point.”

McIntyre said that anything above 617 Route 146, Staucet’s Nursery, is “pretty much going to be out of the question as far as [a] service area without a pump station.”

McIntyre said he’d spoken in the past with Altamont about an interconnection but the cost would have been “overwhelming to have our water pressurized to their system.”

The pressure in Altamont’s water system, according to McIntyre, is 130 pounds per square inch — Guilderland’s nearest water line, at the intersection of routes 146 and 158, is one-fourth that pressure.

“So,” McIntyre said, “there’s a lot of cogs here.”

Kovalchik then sought to succinctly summarize the problem. “From my understanding, then there’s potentially an existing water quantity and water, possibly, pressure issue?” Kovalchik said.

“That’s the big thing; you can’t supply pressure of any kind to them,” McIntyre said. As a “rule of thumb,” He said, “we got to be able to supply 35 pounds [of] pressure at its highest elevation — and that’s not even attainable.”

Prior to McIntyre’s explanation, Bianchine had been under the impression that the 5,800-foot water-line extension would have had enough pressure to supply the entire 41-lot development.

Bianchine reported that the village did say there was enough capacity in its wastewater treatment plant for 37 of the lots to hook up to the village sewer system; the four homes at the end of Armstrong Drive would have septic systems.

Lot layout

To determine the number of lots allowed in a conservation or cluster development, Guilderland’s code says a developer has to submit a conventional subdivision plan to show the number of buildable lots that are allowed by an area’s particular zoning.

The proposed development is located in the Residential-Agricultural3 zoning district, where the minimum conventional lot size is three acres. For a cluster development in the RA3 district, the minimum lot size is 20,000 square feet.

The 37 lots accessible from Gun Club Road would vary in size from a half-acre to 1.2 acres, while the four lots on Armstrong Drive would be five acres each.

A developer receives a density bonus, in the form of additional buildable lots, for providing “certain amenities,” for example, putting in sidewalks, protecting historically-significant resources, or allowing public access to conservation areas “in their cluster/conservation subdivision,” according to the town’s zoning code.

With the proposed conventional subdivision layout, Kovalchik said, “We identified a few lots that might be difficult to build on,” as many as five or six, due to the parcel’s proximity to the Bozenkill.

The Bozenkill flows directly into the Watervliet Reservoir, and town code requires a 250-foot setback on either side of a watercourse draining into the reservoir, which is the town’s major water source.

Planning board Chairman Steve Feeney said he didn’t see allowing credits for lots in the floodplain, “and some other issues I saw”; he counted about six lots that would be undevelopable because of their locations.

Parts of the 159-acre site, which is actually three separate parcels, sit in flood zones designated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and have varying degrees of flooding severity in addition to the property containing wetlands.

Neighbors’ concerns

Nearly all of the seven residents who spoke during the Feb. 16 meeting talked about the water issues with the site in addition to voicing their general displeasure with the proposal.

Dana Welch of Armstrong Circle said, “Every year, or whenever we have a significant rain or the snow melts,” residents have a problem with the water streaming down Route 146 and into the circle, flooding the area to the point where the town has to come and clean out the sewers so the water can drain.

Joe Pasquarella of Armstrong Drive spoke of the wetlands on the proposed development site.

He said that, during the “springtime thaw, our sump pumps are out of control in this neighborhood. I mean, I have a gas-powered trash pump,” which can rid a basement of seven times the amount of water of a lower-end plug-in pump in the same amount of time, “that I put down on my pit to get the water out of here.”

Pasquarella said the area has a high water table, and any type of construction or development is going to send the water in search of an undisturbed place to settle.

“And I don’t want it in my cellar,” he said, “and I will hold the town responsible if this goes through.”