Guilderland's Gold Star fathers: They lost sons to a war America has now lost

“We’re just devastated,” said Raymond Clark.

Clark is the father of Lieutenant Colonel Todd J. Clark, killed in an insider attack by an Afghan National Army soldier on June 8, 2013, an attack in which two others were also killed, and three wounded.

The elder Clark is one of three Gold Star fathers in Guilderland who have lost a child to the war in Afghanistan. “The day my son died was the worst day of my life. And this, the world events right now, comes a close second.”

The Taliban was in power when the United States began its war in Afghanistan 20 years ago, and the Taliban is back in power now. The United States had hoped to see a stable democracy there, backed by a strong military, but this hope crumbled within just days of the last United States troops leaving.

Clark, who is known to his friends as “Jack,” said he was not yet able to formulate many clear thoughts about recent developments, but said the troop pull-out did not seem well planned strategically.

“At least they haven’t forgotten about the Gold Star families,” he said.

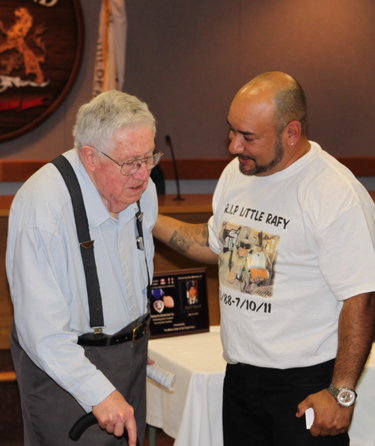

Enterprise file photo — Melissa Hale-Spencer

Jack Clark listens to the national anthem at an event supporting Wounded Warriors held at the American Legion Post in Altamont.

Many newscasters, he said, have been telling viewers to remember people who have lost loved ones in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other parts of the world in the global war on terror. Military generals have gone on television to say to the Gold Star families, “Your children’s deaths were not in vain,” he added, his voice cracking.

LC Clark served a total of seven deployments, including five combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. During his fourth combat tour, in Afghanistan, he was hit with an IED, an improvised explosive device, and he then spent eight months recuperating at Walter Reed Hospital where he became involved in the Wounded Warrior Project.

On his fifth and final tour, he had returned to Afghanistan as a senior advisor to the Afghan National Army, and he commanded the base where he was killed, the largest forward-operating base in Afghanistan, serving with the 10th Mountain Division.

Rafael Nieves Sr., whose son was the only one of the three who died in combat, tried to articulate his feelings about the way the war ended. “It’s sad, and it’s — I don’t know what to think any more. I feel like we just went in there for nothing. My son lost his life for no reason.”

Army Specialist Rafael Nieves Jr. was 22 when he was killed on July 10, 2011, shot in the chest as he manned the top of a tank and returned fire while on patrol in a remote region near Afghanistan’s border with Pakistan.

Serving with the 101st Airborne Division, he had been stationed overseas as an infantryman since the previous November. He was scheduled to return home just two weeks later, where he had a wife and two small children waiting.

“We should be in Afghanistan right now,” said his father, who owns AC’s Towing and Recovery with his wife. His tow truck is emblazoned with his son’s photo, the Stars and Stripes, and the word “NEVER FORGET.”

He added, “I think our president should never have pulled our troops out. We had everything under control.”

But Nieves also said he takes comfort in knowing his son died doing something he loved.

Another insider attack

Major General Harold J. Greene, who died on Aug. 5, 2014, when he was 55, was the highest-ranking officer killed in an active combat zone since the Vietnam War. Major General Greene was an engineer, serving his first tour in a combat zone. His primary task was to put in place training programs for the Afghan military and provide the needed logistical support for those programs.

He was shot, his father Harold F. Greene recalled, by a member of the Afghan security team tasked with “sweeping” the areas through which dignitaries would pass as they visited, ensuring that the buildings were free of threats. He and other officials were, at the time, visiting the country’s equivalent of West Point, the premiere training ground for military officers.

“The security team were trusted people,” said Jon Greene, the major general’s younger brother, whose home the elder Greene was visiting. “They have to be, right? You go by guard towers and other places where there are armed people.”

He continued, “I’ve gone over this a thousand times in my head. Why was this guy allowed to have a gun that close — but you do have to trust somebody. No one anticipated that the threat would come from the security team.”

Harold F. Greene is not surprised by Afghanistan’s fall back to the Taliban. “This was a country that was still highly unstable, and could have gone either way, toward democracy, or, what would you call it, to a force-based country,” he said.

The elder Greene views current events through a long lens. He doesn’t see the recent Taliban takeover as a catastrophe, he said, or even as an ending. “To go back to Europe after World War II, there’s an evolution that brings a country back toward democracy, even after Taliban types of governments take over.” Change like that, Greene said, is “an evolving type of thing that happens over a period of years.”

His son had told him, the year he was killed, that the United States’ efforts to build a strong Afghan military were making progress, but still had a long way to go before the Afghans would be able to support themselves.

“Maybe they never reached that point,” Greene said this week. Best-case scenario, he continued, Afghanistan has a “long, hard road in front of it.”

And the United States no longer has internal contacts or input into decision-making, Harold F. Greene said. “By itself, that can be expressed as a loss if you want to.”

He said that both the United States and Afghanistan lost a lot with his son’s death.

The fathers of both LTC Clark and MG Greene are veterans. Jack Clark had a career in the Army and retired as a colonel. Harold F. Greene spent 14 months in Korea between World War II and the Korean War, went to college on the G.I. Bill, and spent about 30 years teaching high school math and science.

Because of his military background, he is better equipped to deal with the way the war ended than are his wife and son, said Clark. But even so, he cannot stop watching the news that is the source of so much consternation.

Jon Greene said his father had told him a couple of nights earlier that the United States had had two goals in Afghanistan and that one was successful: protecting the United States from potential attacks at home. The other goal was to make that permanent, by helping build Afghanistan into a stable democracy.

“And that unfortunately won’t happen,” Jon Greene said.

Sources of support

Clark brightened when asked about his grandchildren, Todd’s children.

He explained that Madison, his granddaughter, 21, will graduate in December from Texas A&M, Todd’s alma mater, with a degree in special education and then come north to pursue a master’s degree at the University at Albany.

Grandson Collin is a second lieutenant in the Army, and will serve in the Second Cavalry Regiment, where his father was a troop commander. Clark said, “My grandson’s going to be a great officer; he’s phenomenal.”

Clark is looking forward to the seventh annual T. J. Clark Memorial Golf Tournament, coming up this year on Sept. 11, at the Western Turnpike Golf Course. “September 11th was the only date they had available,” he said, and that date seemed very appropriate to him. The event always starts off with a ceremony featuring local veteran-motorcycle groups, which have been a constant support to his family, he said, as well as a bagpiper and a chaplain.

“When Todd came home,” he said, referring to his son’s final flight back from Afghanistan, 250 members of the local chapters of the American Legion Riders and the Patriot Guard Riders were there to honor him at the airport.

The golfing event earns about $20,000 each year for veterans’ organizations, said Clark. “This is my way of giving back to the community,” he said. He added, almost under his breath, “besides sacrificing my son.”