As the last shots are fired in the War on Pot, the injured must be tended to and the cities rebuilt

With the New Year, both of New York’s legislative houses will be dominated by Democrats, giving us hope that long-stymied progressive legislation will be passed.

This month, Governor Andrew Cuomo, charging into his third term, set out his goals for his first 100 days in office. Among them was legalizing adult use of recreational marijuana. He spoke of how the criminalization of cannabis led to “needless and unjust criminal convictions.”

We could see this coming when Cuomo switched from calling marijuana a “gateway drug” to calling for a study to evaluate the health, public safety, and economic impact of legalizing marijuana in New York. We read the report, issued in July, which concluded the benefits of a regulated marijuana market outweigh any drawbacks, and called for New York to take the next step. The state had, in 1977, decriminalized having small amounts of pot and then, two years ago, allowed New Yorkers to get the medicine they need for a limited number of serious diseases.

The next step is to craft legislation that addresses potential ill effects — educating police on identifying drivers who are high, and educating parents on the need to keep edible marijuana products out of the reach of children.

Illegal marijuana is already here. It must now be regulated so that the product New Yorkers use is safe.

As we wrote in August, the proceeds that come from taxes on legalized cannabis should be used to help bridge the ever-widening gulf in our society, between the rich and the poor, to help the communities most harmed by unbalanced prosecution and incarceration.

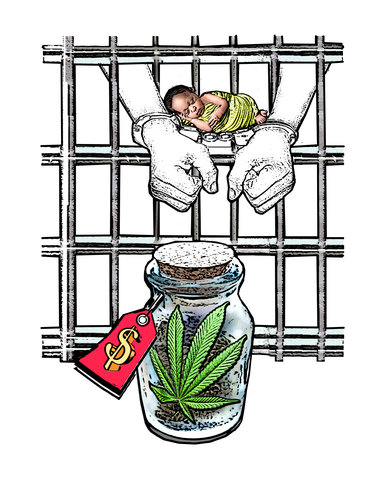

Although data shows equal use of marijuana among racial groups, the July report notes a black person is almost four times more likely than a white person to be arrested for possession of marijuana. This is despite the fact, as Albany County’s district attorney, David Soares, pointed out, that many of the criminal enterprises are rooted in suburban communities.

This week, our reporter Sean Mulkerrin has taken a deep dive into the history in our country of black and Latino people being targeted in marijuana arrests. Last year, over 23,000 New Yorkers were charged with marijuana possession — 80 percent were black or Latino.

Soares presented to the State Assembly this fall what he calls the “Marihuana Marshall Plan,” trying to set right the harm done by the so-called War on Pot just as the Marshall Plan did with aid to a ravaged western Europe after World War II.

We endorse the broad strokes of Soares’s plan — helping the communities hurt by the decades of arrests and imprisonment would strengthen New York as a whole.

But, as Mulkerrin’s research makes clear, the devil can be in the details.

The easiest and most needed part of his plan, Soares told the Assembly in October, is “to redress the stigma of criminal convictions among our black and Latino populations who have borne the brunt of the War on Pot.” The next month, his office stopped prosecuting cases that involved only possession of a small amount of pot.

But Alice Green said is not as easy as it sounds to appeal convictions or seal cases. We trust Green’s assessment. She is the executive director of the Center for Law and Justice in Albany and has been a tireless advocate for the city’s often mistreated African Americans.

Many people don’t know how to appeal or are not aware that they can. Mulkerrin showed this is true by looking at states where cannabis has been legalized and systems have been set up for residents to clear records of past convictions — very few have.

So we urge our lawmakers as they go about drafting legislation on legalization that they include requirements to have some of the tax revenues spent on outreach and education as well as on legal help for former offenders to clear their records.

Soares’s plan also calls for jobs in the new industry to be given to those who have been hurt by earlier arrests. He correctly notes that a lack of healthy economies in urban areas has led to the growth of an illicit economy.

New Yorkers have to make a decision, Soares said: They can either surrender to already-established industries or force their leaders to invest in underserved communities. Mulkerrin details how those businesses licensed to deal in the state’s current medical-marijuana program are often multi-million-dollar companies, foreshadowing what Soares sees as likely to happen if the state legalizes recreational marijuana.

“You’re going to see the major industries come into New York. They will throw one fundraiser after another for both parties,” said Soares, “and they will offer a very easy way for New York State to get on board.”

We urge our leaders, rather, to see that the communities hurt by the War on Pot get a fair chance to be part of the profits that will come with legalization — for example, setting up low- or no-interest loans with advisors and oversight for small businesses. Mulkerrin reports on research showing that, in the states where pot shops are legal, only a tiny percentage are owned by African Americans.

But, Mulkerrin also cites an example of at least one local government — the city of Oakland in California — that set up a system in which half of all cannabis permits are to go to “equity applicants” who earn below 80 percent of the city’s median income and have either a marijuana-related conviction or have lived for 10 of the past 20 years in areas with a disproportionately high number of pot-related arrests.

We urge our state legislators to keep models like this in mind, and failing that, for Albany County to look into creating its own program that would help those who have been hurt by earlier arrests.

Mulkerrin highlights a caveat from the Citizens Budget Commission, which notes some states have collected less in tax revenues than they anticipated when legalizing marijuana. July’s New York State report estimated the state’s current illegal marijuana market to be $1.7 billion to $3.5 billion a year and estimated a legalized system could generate between $248 million and $678 million in tax revenues.

We believe a large percentage of those revenues should be used to invest in the communities hurt by past drug policies. This would include money for education, job training, and transitional housing and help for people returning from prison.

Countless New Yorkers have had their lives derailed by draconian drug laws. We can’t undo the past — we can’t make whole the families that were severed, replace a sense of self-worth that was ripped away, or restore the jobs and opportunities that were missed because of incarceration.

The slate will never be wiped clean but we can write upon it a clear message of restorative justice. It will benefit all of us — those who are poor, those who are part of the ever-shrinking middle class, and even those who are rich — if we help the communities that have been most hurt.

How?

If a neighborhood has a healthy economy, its residents have hope and opportunities for a decent future. If not, the tendency is to create an illicit means of making money, to turn to crime.

As a society, we are hurt by this — and not just because of the legal and prison costs — but because we’ve trashed the futures of people who could contribute to the common good.