Street psychiatry in Albany County will provide a much needed safety net

Homelessness is a national shame and a problem right here in Albany County.

But homes alone are not enough to solve the problem.

While we’ve commended on this page efforts to find safe havens for people on the street — especially programs like Sheriff Craig Apple’s use of decommissioned portions of the county jail, which also provides social services and support — treating the problem at its source, on the streets, is the best way forward.

We commend Albany County for a street psychiatry program launched as a pilot program last week and urge support to make it grow and flourish.

From 2020 to 2024, the number of people without homes in Albany County has increased 27 percent, from 676 to 857. In that same period, the number of homeless people living in the county with behavioral health issues has increased by 67 percent, from 162 to 271.

These numbers were reported last week at a press conference announcing the new pilot program.

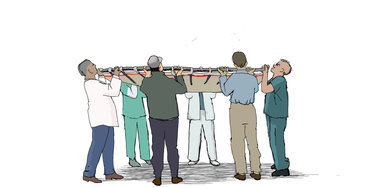

“We’re going to meet them on the street with a team,” said Albany County Executive Daniel McCoy. The team, he said, will consist of six people: a nurse, a mental-health clinician, a case manager, a mental-health peer advocate, an alcohol- and substance- abuse counselor, and a medical professional.

McCoy stressed that homelessness is not just a problem in the city of Albany but throughout the county.

“Colonie has issues, Cohoes, Watervliet, Green Island, Bethlehem, Guilderland … it’s throughout the whole county,” he said, concluding, “We cannot address the homeless crisis without addressing the mental-health crisis.”

We lauded on this page, in 2023, the united efforts the city and county of Albany, working with court and state leaders as well as charitable institutions, were making to address the triple scourges of mental illness, drug addiction, and homelessness.

The leaders literally stood as one at a press conference to tout the various programs — a veritable alphabet soup of acronyms — that would both help those in need while improving the quality of life for everyone in Albany.

The street psychiatry program is the next step on the progressive path that Albany has chosen to stop the triple scourge.

Albany has an added burden as its mayor, Kathy Sheehan, noted, because of its regional trauma center.

“Everyone with mental-health challenges that ultimately requires an emergency-room visit are typically coming to the city of Albany,” she said. “They are getting some form of treatment but too often they are being discharged right out onto the sidewalk.”

Sheehan called the pilot program “a game-changer.”

Brendan Cox, Albany’s interim police chief, said that public safety is about more than just crime; it is also about public health.

Citing crime data, Cox said, “We can talk about the fact that crime continues to be lowered in our city, and people can continue to say, ‘Well, I don’t feel safe.’”

That is because of the many unsheltered people with behavioral health issues, he said.

“A lot of people are living with substance-use disorders, with mental-health issues, and are living in very public view … They need help … and people want to see a response.”

Many calls police answer — made when residents upset with street people call 9-1-1 — are often not issues that should be handled by police, Cox said.

Of the pilot program, he went on, “Now we’re going to be able to have a boots-on-the ground response for a clinical response, and it’s going to build into an entire spectrum of responses.”

This will free up police officers for other duties and increase public safety, said Cox. “We’ll especially see people on the street lifted up,” he said

The city and the police are contributing funds to the program, which is also supported by the county legislature and it is being funded in part by $250,000 guaranteed by the city of Albany and its police department, part of Governor Kathy Hochul’s $400 million budgeted for Albany.

Nationwide, there are more than a dozen multidisciplinary teams providing psychiatric care to unsheltered people, according to a 2023 article published by the American Psychiatric Association’s Psychiatric News.

The goal of street psychiatry isn’t to provide lifelong care on the street, the article stresses; rather, the goal is to get individuals stabilized enough so that they can get care at a clinic and relaunch their lives.

Homeless people have a 30-year shorter life expectancy than people who are housed, the association says. And the United States has more homeless people than any other similarly developed nation: more than 580,000 in January 2022, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The number of disabled, chronically homeless people rose 16 percent between 2020 and 2023. Estimates vary, but it is believed that as many as half of homeless people have substance-use disorder and/or serious mental illness.

“Many of my patients use meth for their survival; it helps them stay awake at night because it’s not safe to sleep after dark, especially for women,” said one of the psychiatrists quoted in the Psychiatric News article. “Then they use opioids to help them sleep during the day ... It’s a real challenge to help patients reach their recovery goals when they live in the same traumatic living situation that perpetuates this cycle.”

In an interview for the Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative, Katherine Koh, a psychiatrist at the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program and a member of its street team, who also teaches at Harvard Medical School, explained, “There is a bidirectional relationship between homelessness and mental illness. Many think mental illness leads to homelessness, but importantly homelessness can lead to mental illness as well.”

Often, people who become homeless have pre-existing mental illness that was not treated appropriately or was exacerbated by other factors, Koh said, such as poverty or adverse childhood experiences, or loss of a relationship.

“It’s not mental illness itself, but lack of systems of care for people with mental illness that leads to homelessness,” she said. “Homelessness itself is such a challenging, often dehumanizing, traumatic experience that people who don’t suffer with mental illness can develop a mental illness like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or an existing mental illness can be exacerbated.

“Homeless people also struggle significantly with substance use disorders,” Koh said. “Many homeless people say they use substances merely as a way to survive the hardships of the street.”

A study her group conducted found that the three strongest predictors of becoming homeless were: having a lifetime history of depression; a lifetime history of PTSD; and having a trauma of seeing a loved one murdered.

Koh went on to contrast her patients who have a home with those who don’t. The mortality rate among people on the street is significantly greater.

About 40 unhoused patients followed by Koh’s street psychiatry team die every year, or one patient every one to two weeks. By contrast, in her clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital, over the past four years, one patient has died over that entire time,” Koh said.

“Every death is hard, and every death is meaningful to me,” she said.

An interdisciplinary approach to street psychiatry, like the one Albany County is piloting, is essential, Koh said.

“Studies show that unhoused people are more likely to engage with mental health care if it’s paired with case management or physical health services,” she said. “Oftentimes, mental-health care is not the first priority. People are understandably often more focused on housing or case-management needs, and so that’s what they’re going to seek first.”

Koh said she is often asked by people what should be done for a homeless person — give them money? Buy them food?

“People fundamentally more than anything want to be seen, to be understood, to know that they matter, to be loved and respected for who they are, …” said Koh. “Almost every person who has experienced homelessness says what matters most is being looked in the eye, just hearing hello or good morning, or just an acknowledgment of their humanity, who they are as a human being.”

As individuals, each of us should follow her advice.

But collectively, we can do more. We’re glad we live in Albany County, which is working in a constructive way to solve its homelessness crisis.

This is different from, say, Saratoga Springs, which has proposed a law that would fine people for sleeping on the sidewalks or in the parks. Such an approach won’t help the people on the street nor will it help the society at large.

As Chief Cox pointed out, public safety will be improved if people on the street are helped and police can attend to other duties.

And Mayor Sheehan made the critical point that the street psychiatry program is sustainable only when the federal Medicaid program reimburses for mental-health services.

“Once individuals get the case-management that they need, most of them qualify for Medicaid," Sheehan said. “And Medicaid needs to have parity in paying for these mental-health services because it works and it ultimately saves dollars.”

In May, the House of Representatives passed, by one vote, its fiscal year 2025 budget reconciliation legislation — dubbed by Speaker Mike Johnson “one big, beautiful bill.” On June 28, the Senate voted, 51 to 49, to move its reconciliation legislation, leaving just a sliver of time before it is adopted to persuade legislators of the need to maintain Medicaid.

Sheehan said of the Medicaid investment, “That is the glue that allows this to really stick and become best practice that our residents can rely on when the next person falls into either having a traumatic situation or a mental-health crisis … What is happening is people are literally dying on our streets. And it has to stop.”

We, as a society and as individuals, have the power to help. It is, indeed, a matter of life and death.