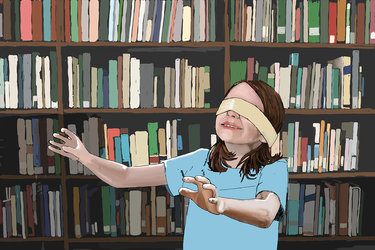

Our children cannot find their way without the freedom to read a variety of views

“Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.”

That quotation provides the justification for the Freedom to Read Act proposed by New York State Senator Rachel May, a Democrat from Syracuse.

The words were written by Harper Lee in her 1960 novel “To Kill a Mockingbird,” which won the Pulitzer Prize and is considered a classic of American literature. The book, which deals with racial inequities, has been banned and subject to campaigns to remove it from classrooms.

The words likening reading to breathing are spoken by Jean Louise Finch, known as Scout, the girl who narrates the story of life in a small Alabama town in the midst of the Great Depression.

Breathing is essential; we cannot live without it. So, too, is reading essential for a democracy; a democracy cannot survive without an informed citizenry.

In a June 9 celebration of the freedom to read, “Open Books, Open Minds,” Rachel May conversed with school and public librarians.

While she was never a librarian herself, May said, she has used libraries extensively pursuing advanced degrees and working as a college professor and using archives around the world.

“I raised a kid who was a complete book-aholic,” said May, sharing an anecdote about her child’s third-grade teacher asking the class to name their favorite things. Her child answered, “A delicious pile of books.”

May said she is driven by her own childhood memory of her beloved grandfather, an American historian who taught at UCLA.

“In California,” she said, “after the Civil Rights Act passed, the state put out a call for a new eighth-grade American history textbook that was more reflective of all of American history — history that included slavery and Jim Crow, included the labor movement and a number of things that just had been completely neglected in textbooks up to that point.”

Her grandfather, she said, collaborated with two others to write an inclusive text book “to meet that moment.” The John Birch Society chose the book as its number-one target, May said, leading to death threats aimed at her grandfather.

Nevertheless, California adopted the textbook “but there were mothers who were taking their kids out of history class so that they wouldn’t have to read about Harriet Tubman or Frederick Douglass,” she said.

May’s grandmother contributed all the teaching supplements for the textbook, testing them out on May, who was 10 years old at the time, and on her brother, she said.

“It was a real education of what censorship or attempts at censorship look like and what a flashpoint just trying to tell the full story of American history,” said May.

What is different now from earlier attempts at book censorship and purging our nation’s history, beyond the prevalence of such efforts, is that the initiative is being carried out by our federal government — a government that has lost the Constitutional checks and balances among its three branches: the executive, legislative, and judicial.

We have elected a president who is ignoring the Constitution, attempting to run the nation through executive orders, largely bypassing Congress on everything from imposing tariffs to deploying “his” troops against protesting citizens in California despite the governor’s objections.

That is why we need May’s bill to become law; it will give young New Yorkers the chance to learn history, and to understand themselves and the world around them. The Freedom to Read Act has now passed in both houses. We strongly urge the governor to sign it into law.

Last month, the American History Association, backed by a slew of other organizations, released a statement condemning “the removal of 381 books, including acclaimed historical works and widely used primary sources, from the United States Naval Academy’s Nimitz Library” as well as “what appears to be the expansion of this censorship policy to the full universe of military academies and other education institutions.”

The association correctly states, “Removing books that are based on careful historical research won’t make the facts of our nation’s history go away. But it will render the military unprepared to face their legacies and our future.”

When May voted in favor of the Freedom to Read Act, she said that last year there was a 92-percent increase in the number of titles targeted for censorship.

Between 2000 and 2020, there were an average of 265 book challenges a year. In 2021, the number of book challenges jumped to 1,858; by 2023, there were more than 4,200 across the United States including at least 80 in New York.

May said the two most targeted books last year were George Orwell’s “1984” and Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” — “both of which should be required today as we try to understand our country’s descent into authoritarianism,” said May.

The wording of the act is simple and straightforward. It would require the commissioner of education and school library systems “to develop policies to ensure that school libraries and library staff are empowered to curate and develop collections that provide students with access to the widest array of developmentally appropriate materials available.”

The justification for the act says that “‘protecting’ children from negative information or harsh realities about issues like the history of slavery or injustice serves to make them less resilient and less vigilant about preventing such outcomes in the future.”

It notes that New York is a diverse state and young readers need access to varied perspectives.

“Whether they embrace or reject those perspectives,” it says, “the opportunity to explore challenging ideas is valuable to students’ development as learners, as community members, and as citizens.

“Democratic self-government depends on a free exchange of ideas and information ….”

At the June 9 “Open Books, Open Minds” session, librarians told May that, across New York state’s 735 school districts, there is a “patchwork quilt” of policies — or sometimes no policy at all — on book selection for libraries.

A librarian from a public library on Long Island said, “There is a man who goes from library to library with a giant inflammatory sandwich board to really intimidate people from even entering.” Public libraries, she said, are to provide access, not to endorse ideas.

“Without that bedrock principle in place, what does democracy look like?” she asked.

The American Library Association, which tracks censorship across the nation, has found that nearly three-quarters of attacks are coming from pressure groups rather from a concerned parent or community member.

“It’s a coordinated playbook attack on libraries,” said May.

Another librarian, who works with teenagers in a public library, said, “There is nothing more magical than a young person finding himself reflected … when they see their story represented or someone who looks like them or thinks like them, the love of learning and the desire to learn even more about the world just increases.”

She concluded of youth, “We want them to be open-minded and open-hearted and that comes from literature that shows who they are.”

Still another librarian spoke of having a wide array of books available as “a social-justice issue, where every child has a right to see themselves in an affirming way … And it’s also an equalizer,” she said, noting some communities are not diverse so people develop implicit biases “due to their limited exposure to certain people and groups. They need to see a beautiful diverse world as well.”

Beth Davis, the longtime school librarian at Berne-Knox-Westerlo, spoke to us in 2022, which then seemed a “scary time” for librarians, about her guiding light: a thought from Rudine Sims Bishop, who has been referred to as the mother of multicultural children’s literature — librarians need to provide books that are both windows and mirrors.

“You need to be able to look in a mirror and see yourself in a book,” said Davis. “But you also need to be able to look through a window and see others and the rest of the world and love that.”

This week, we spoke to the director of the Guilderland Public Library, Peter Petruski, and to the Superintendent of Guilderland schools, Marie Wiles, about the Freedom to Read Act.

Both the school district and the public library have board policies in place that do just what the act calls for — empower professionals to curate and develop collections that provide readers with access to the widest array of developmentally appropriate materials available.

“Not only do we empower them to do that work; that’s what we’ve hired them to do,” said Wiles.

“We have over 10 librarians who take responsibility for different sections of our collection, be it adult or children’s, our AV material, our audiobook, our DVDs …,” said Petruski. “We rotate the staff members who are responsible for each section just so that we have a diversity of viewpoints contributing.”

He went on, “The important thing for us is that the choice is with the reader or with their parent or guardian. That way, we have a broad collection that the community can choose from.”

In the year he has been at the helm in Guilderland’s public library, Petruski has not fielded a single complaint on a book, he said.

Wiles said the school district gets occasional complaints and has a committee of teachers, librarians, parents, and administrators that read the book in question and assess its appropriateness.

The last complaint she recalled was several years ago about “Lawn Boy,” Jonathan Evison’s semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story, which the American Library Association reported in 2022 was the seventh most banned book in the nation that year because of its LGBTQA+ content. The Guilderland committee deemed “Lawn Boy” was appropriate for the high school library.

Asked if she thought the Freedom to Read Act is needed, Wiles said, “I would like to think it doesn’t need to be, but we live in a time now that things we believe to be self-evident, maybe are less so, which is a very depressing thing to say.”

Answering the same question, Petruski referenced the recent abolition of the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services and said that such cuts are “really a statement of intent or a statement of values.”

He went on, “I would like to live in a world where these protections didn’t have to be legislated, but with the national conversation that’s happening, I’m happy that our elected officials are trying to protect our ability to do our job.”

We salute our librarians — May called them “warriors for our kids, and for the truth, and for the First Amendment” — and again urge the governor to sign the Freedom to Read Act.

We’ll conclude with the U.S. Naval Academy’s view on the importance of history because it applies to all of us:

“We cannot understand the world today without knowing how it got that way — which is to say through history, the discipline that seeks to explain why everything came to be as it is. In the real world, everything — politics, economics, religion — is connected to everything else, and so is the process by which people decide and act, by which history unfolds….

An effective leader masters the past in order to more effectively shape the future …. Lost leaders are a danger to the people they lead. Lost citizens are a danger to themselves and to their fellow citizens.”