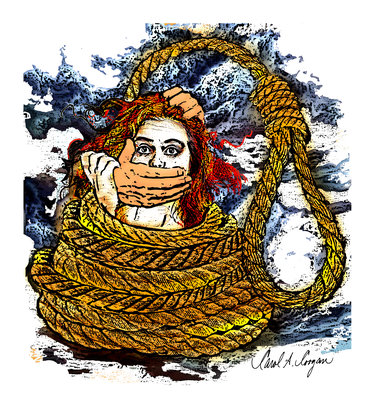

We must stop the nightmare of rape by standing together behind the survivors

Rape and sexual assault are heinous acts that we, as a society, have to deal with. Each and every one of us needs to pay attention.

Most rapes go unreported. Why? Often because the women who have been assaulted feel shame.

The shame is not theirs. It belongs to the perpetrator and to the society that so easily misjudges.

Women are raped on college campuses by men who are supposed to be colleagues. Women are raped in the military by men who are supposed to command them with respect. Women are raped in their own homes by men who are supposed to love them.

We’ve written editorials in this space about each of those situations — again and again for decades — because such attacks have happened in our midst.

We’re writing this time because the need is still strong and the revised Albany County Charter, up for public vote on Nov. 3, has an article that would include the Crime Victim and Sexual Violence Center as one of the services the county provides.

Mind you, this is not an editorial endorsing the revised county charter. Our readers can read our story on the charter and make up their own minds.

What we are advocating, whether or not the revised charter passes, is making the center part of the charter.

In 1974, a group of volunteers started a much-needed rape crisis center in Albany; the next year it became a county department.

The appropriate acronym for the volunteer center was AWARE — Albany Women Against Rape — because, in that era, people were just becoming aware rape was a crime. There is still a stigma; that’s why rape survivors often don’t report the crime to police.

Only about 10 percent of women who are raped go to a hospital emergency room and, of those, only about 10 percent press charges. The Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network estimates that one out of six women will be sexually assaulted in her lifetime.

When survivors remain silent, the perpetrators of sexual assault go unpunished. If they were jailed, they wouldn’t be able to repeat their crimes.

Many survivors of sexual assault feel shame and feel they are re-living their trauma as they are questioned about it by police or if they testify in court. This is where the center can ease the way, educating police and court officers on ways to ask questions that are healing and not traumatizing.

The center also helps survivors gain the confidence to speak up. Volunteers there are taught “the art of victim advocacy,” as a training guide puts it. “An advocate is informed, educated on the complex systems involved, able to find an answer to a question they may not know, and, most importantly,” the guide says, “able to empower the victim.”

Counseling guidelines inform volunteers that victims often have difficulty communicating, many times not even being able to verbalize the crime. The counselors are to “provide a safe and supportive atmosphere for the victim to ventilate her feelings. Guilt, fear, and anger need to be discussed and dealt with in a positive manner.”

Counselors are urged, “Point out the victim’s strengths to her. She may feel helpless and out of control of her life. Help her to see that her inner resources helped her survive the assault. Her request for therapeutic intervention is also a strength. She may not be able to recognize this for herself at this time.”

The center, which provides escorts for hospital visits and advocates for court matters, helps people of any age who have been assaulted at any time in their lives, even decades ago. The counseling is free and confidential.

Bryan Clenahan, a Guilderland representative to the county legislature who is running unopposed for a third term, has long been a champion for the center.

He noticed the center was not set out in the current charter. “My feeling was this is such an important service and we need to memorialize it in the charter and make it permanent,” Clenahan told our reporter Anne Hayden Harwood this week.

Clenahan well knows the need for such permanency. A decade ago, the county executive at the time proposed a budget that dismantled the center. Then, five years ago, in the depths of the Great Recession, massive cuts were proposed to services.

At that time, Clenahan wrote a resolution, passed by the legislature, that current services be maintained. This week, Clenahan said, if the revised charter is defeated at the polls, he’ll re-introduce a charter amendment next term.

We wholeheartedly back this. A full array of services is needed. A woman doesn’t choose when to be raped and she has to have help in her moments of greatest need — when she is deciding to go to a hospital where a rape kit can be used to gather evidence, when she is debating pressing charges and has to speak the unspeakable to a police officer, when she is testifying in court where she fears being belittled as a slut.

The numbers are staggering, and behind every statistic is a woman in pain. This month, because October was Domestic Abuse Awareness Month, Albany County issued a release stating there were nearly 2,000 cases of domestic abuse reported in Albany County. We see them every month in our blotters column and we recognize that those reported cases are just a fraction of the actual abuses.

The need is high. According to Kathleen Magee, director of Domestic Violence Services for Equinox, the not-for-profit center served more than 2,000 victims of domestic violence this past year, including 225 families that used the Equinox shelter. More than 300 other families had to helped in out-of-county shelters because there wasn’t enough room here.

Once someone — often a mother with children — screws up the courage to leave a violent home, it is essential she be able to find safe shelter.

This year, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed “Enough is Enough” legislation designed to combat sexual assault on college campuses in New York, requiring colleges to adopt procedures and guidelines including a uniform definition of affirmative consent, an amnesty policy, and more access to law enforcement.

Such enforcement is badly needed. A study this fall by the Association of American Universities found that 23 percent of college women were sexually assaulted.

Further, the survey found that only 37 percent of female undergraduates at the full set of private and public AAU institutions surveyed and only 25 percent of female undergraduates at the subset of private AAU institutions believed campus officials would take a report of rape seriously, conduct an investigation, or take action against an offender.

We need to stop the stigma. In no other crime does the victim feel shame. In no other crime are the victims unwilling to tell police. And in no other crime do institutions like colleges downplay or even cover up the crime.

Sound and permanent help from a government-backed Crime Victim and Sexual Violence Center is essential. Not only does it provide much-needed help to anyone in the county — whether a college student suffering date rape or a battered woman fleeing her home — it sends a message.

The message is this: The government — made up of we, the people — stands behind women who survive rape.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer