Irena Altmanova Frinta

ALTAMONT — Irena Altmanova Frinta was ahead of her time in combining her career as an artist with her role as a supportive and loving wife and mother, said her daughter, Dagmar.

As a girl, growing up in Czechoslovakia, Mrs. Frinta had twin passions — writing and art. She chose art for her career but, in her later years, at age 95, published a novel.

She died on Wednesday morning, Sept. 25, in her Altamont home. She was 96.

Mrs. Frinta was born on Sept. 3, 1923 in Plzeň in Czechoslovakia, now the Czech Republic. She was the second child of Jaroslav Altmann and Hermina Altmonova. Her father, whom she described as a sensitive and patient man who “forgave everybody everything,” was an architect for Czech railroads, and her mother taught French.

“Remember how I followed you after supper to the room with a closet that was always locked?” Mrs. Frinta wrote in an Enterprise column she addressed to her father more than a decade ago, long after his death.

“When you opened it, I saw different machines and you named every one of them and let me hear their humming and explained which machine does what,” she wrote. “It was pure magic.”

Mrs. Frinta wrote how she herself had a lifelong love of machines and purchased items from an electric drill and sander to a power saw and saber saw. “I had no training for that, but, if there is something at home that does not work, I push here and I pull there and the machine starts working again. Must be your genes, Daddy.”

She also wrote, “My sister and I called you a dreamer. When you played the violin, your eyes got misty and you were far away … When I take pastels from their box and fasten the paper on the drawing board, I, too, get the same expression — I, too, enter the fairyland and start with: Once upon a time. Must be your genes, Daddy.”

Of her mother, Mrs. Frinta wrote, “If it is true that nobody is perfect, my mother was an exception.” Both of her mother’s parents were businesspeople with stores in the main square of Plzeň — her father imported fruits from other countries, and her mother was the first in town to create and sell ready-made coats.

After her schooling in Plzeň, Hermina Altmonova went to Switzerland to study the French language. She gave up teaching at school after she married and had two daughters, but still taught French lessons from home. She was a good cook, a good organizer, and planned interesting family trips.

While Mrs. Frinta’s father played the violin, her mother played the piano, giving their daughters concerts. “I liked to dance to their music,” wrote Mrs. Frinta. “It was a happy time.”

Her mother read in bed, long into the night, both Western and Eastern literature. “She was interested in the mysteries of life after death … She was brought up as a Catholic. She was faithful to this religion with all it stands for: Love, hope, forgiveness. She believed in the equality of people of different races and religions.”

Mrs. Frinta described her mother as a determined woman with self-esteem who was, in her eyes, “an example of an ideal mother and an ideal woman.”

The secure life of her childhood came to an abrupt end with World War II.

“During the bombing, she said, ‘God, if you spare us, I’ll be a good person and never complain,’” recounted Dagmar Frinta. “She always told me, never complain.”

“All in all, I always needed to paint,” Mrs. Frinta told The Enterprise in 2005. “I always drew and painted from when I was a little girl.”

Mrs. Frinta studied art at the College of Applied Art in Prague. While in college, she submitted her work to a competition and won the prize of an exchange scholarship from the French government to Paris to study at Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts and Academy André Lhote.

In Prague, she had learned the basics of art and focused on drawing techniques. When she came to Paris, she discovered color. She was most influenced by the Impressionists.

“I love color,” she told The Enterprise. She thought it was the most important element in art. “The excitement is in the color,” she said. “I have to have color.”

Her motivation for drawing came “after a big impression,” she said. Then “I put it on paper.” Much of her work was inspired by her travels.

After Paris, Mrs. Frinta started her career by studying oil paints but became allergic to them and didn’t want to have the harmful fumes around her family, so mostly worked in pastels.

“It wasn’t until I discovered pastels that I saw the infinite possibilities of colors,” she said.

“It’s a medium that people think is fragile … but the colors don’t change; they stay brilliant,” she said, contrasting that to oils, which tend to turn yellow.

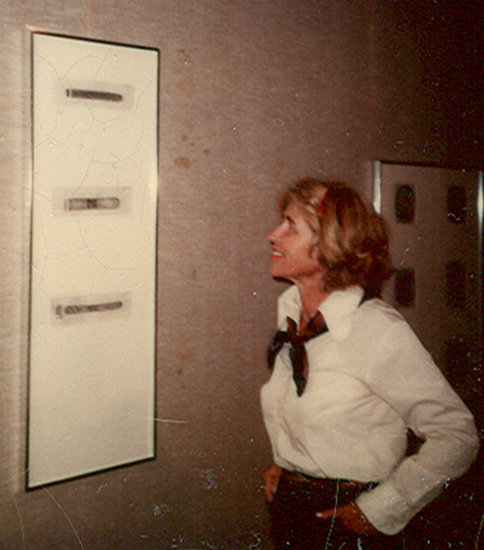

Mrs. Frinta was listed in “Who’s Who in American Art,” was a guest artist at Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, and received prizes and awards for her works, which are in many public and private collections. She exhibited twice in Europe — with shows in Florence and Plzeň — and also in Washington, D.C. and New York City as well as at many venues closer to home.

She wrote in an Enterprise notice about her 1977 show at the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls that she’d wished, since she first saw the ivy-covered Hyde House with its Florentine architecture, that she could have an exhibit of her pastels there. “No wonder I am delighted to be able to exhibit my pastels in such an exceptional setting,” she wrote.

Family

Mrs. Frinta met Mojmir Frinta, also an art student on scholarship, while she was studying in Paris after the war.

Following the war, Dr. Frinta, who was born in Prague, hitchhiked around Europe and saw the terrible devastation. But he also went into the churches and saw “the redeeming beauty of the art made by humans, the goodness and hope of being human,” said Dagmar Frinta.

Dr. Frinta spent the better part of a lifetime restoring, researching, and teaching about that art. He became a world-renowned scholar on medieval painting and sculpture, publishing scores of articles and two books.

The Frintas romance was both swift and enduring. The couple married in Paris in 1948.

Mrs. Frinta worked for International Relief, said her daughter. “She would have money to give to Eastern European refugees.” Referring to playwright Eugène Ionesco, Dagmar went on, “She would sit with Ionesco and his friends, to make sure they didn’t spend the money on wine.”

The couple left Europe for America in 1951.

“It was my mom’s initiative,” said Ms. Frinta. “She was very adventurous.” The Frintas lived for three years with relatives in Flint, Michigan, and then lived in New York City for eight years while Dr. Frinta worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mrs. Frinta became a United States citizen in 1956. When Dr. Frinta got a job as a professor at the University at Albany in 1963, the Frintas moved to Altamont where they raised three children: Daniel, Dagmar, and Richard.

“She was more comfortable in Altamont than anywhere else in the world,” said Richard Frinta. “My dad was the traveler. She loved gardening. Her flowers were so special to her.”

“My mom was very earthy,” said Dagmar.

Mrs. Frinta also raised vegetables in her garden to feed her family. “She grew vegetables, and had fruit trees. She’d can and make jams. We ate well,” said Dagmar. “We had organic food before it was in.”

Dagmar went on, “She kept European traditions alive. I learned to knit in the continental manner. And she sewed a lot of our outfits.” One set of outfits, in velvet, was for both mother and daughter. “She loved fabric,” said Dagmar.

The Frinta children made Czech ornaments for their Christmas tree, cutting saints or angels out of pieces of wood.

Mrs. Frinta also loved her larger surroundings, said Richard, a photographer who lives in California. He said that, in recent years, he would plan his trips home for the fall season so he could enjoy outings to Indian Ladder Farms and to Thacher Park with his mother, who loved the glorious colors. “She loved nature,” he said.

The Frintas made many trips to Europe as a family. “When we traveled, we bonded,” said Daniel Frinta.

“Those were the happiest times,” said Dagmar. “We felt less alone. We were among our cousins, our aunts and uncles, and grandparents.”

Mrs. Frinta’s sister lived in Normandy and the Frintas would visit her there, staying in a cottage where they could walk to the beach. “We could see unexploded shells,” said Dagmar, from the site of the D-Day landing.

When the family traveled to Europe, Dagmar said, “We’d be allowed two outfits.” That’s because their suitcases would be filled on the return trip home with purchases made in Europe. “My father loved carpets and my mother loved ceramics,” she said.

Mrs. Frinta had a close circle of friends, her children said; chief among them was Jitka Jurenka, also from the Czech Republic, who lived in Guilderland Center.

Mrs. Frinta was “a faithful member of St. John’s Church,” said Daniel. “She was raised a Catholic,” said Dagmar. “Her father was an animist, which inspired her love of nature.”

“They exposed us to art,” said Richard. “What I remember most is the appreciation they instilled in us for all the arts,” he said, citing not just his mother’s love of the Impressionists, but his father’s love of classical music.

“We were exposed to countless museums,” said Richard. “I was always excited to visit Europe and the museums.”

“She did a lot of art projects at home with us,” said Dagmar.

When her children were young, Mrs. Frinta said, she dedicated herself to raising them. After they were in school, she taught art as a substitute teacher to make money for her own art supplies. She said she didn’t want to take money away from the family budget so this is what she did to get materials.

When Dagmar was 14, her mother went back to school to get a master’s degree. She completed the degree, from the University at Albany, in 1970.

“She was remarkably ahead of her time, raising a family and having a career,” said Dagmar. “I cooked and cleaned. There was an understanding women helped each other, which helped me in my life … It was good for me to see my mother succeed,” said Dagmar, who is herself an artist.

“She was a good role model for me. She went after her artwork. I did, too. She had her own strong identity,” Dagmar said.

The Frintas’ Victorian home on Maple Avenue in Altamont is filled with Mrs. Frinta’s paintings. Daniel’s favorite is “Blueberry Hill,” of a local scene.

“She did plein-air painting outside like Cézanne,” said Dagmar. “She’d do sketches and do a lot from her feelings of what she saw.”

Referring to a painting of a cornfield on Brandle Road, just outside of Altamont, Dagmar said, “It’s like it’s on fire, it’s so full of energy.”

While her paintings could be fiery, Mrs. Frinta’s temperament was placid. “She was very kindly and concerned about people,” said Daniel. “She was a very practical person, not having her head in the clouds.”

“She felt responsible,” said Dagmar. For example, she said, on family trips, “My mother would do the driving while my father would be studying.”

“She gave a lot of herself,” said Daniel.

“From the moment she got up, she surveyed what had to be done,” said Dagmar. “She was good at detail.”

The entire downstairs of the Frintas’ Maple Avenue home is filled with books, the Frinta children said. “She read about the French painters,” said Dagmar.

“And Harry Potter,” said Daniel.

“She was curious, interested about everything in the culture,” said Dagmar.

Last year, at the age of 95, Mrs. Frinta published a novel, “The Lives and Loves of Three Women,” the story of three young women and their attitudes and approach to love, marriage, friendship, and work. She said she wanted to write an uncomplicated book, a relaxing read in a frantic world.

She also said that she wanted to set an example for other elderly people to prove that, at their age, they could continue to do meaningful work.

At the core of her painting and writing, Mrs. Frinta said last year, was her desire to show people the beauty that is all around them.

“She lived in the present,” her daughter said. “Her love was painting.”

“She was welcoming,” said Richard. “She had a great smile. You could just feel the warmth emanating from her.”

His mother valued friendships and art, Richard said, recalling a conversation near the end of her life.

“She loved Monet … We just sat and talked about Monet,” he said. “To the last day, it was talking about art and friendships. Friendships and art are what she was all about.”

He concluded, “She taught us to appreciate the beauty around us … She had a great heart.”

****

Irena Altmanova Frinta is survived by her children, Daniel, Dagmar, and Richard Frinta. Her husband, Mojmir Frinta, died in 2015.

A memorial service will be held at 3 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 6, at St. John’s Church at 140 Maple Ave. in Altamont.

Mourners may leave condolences online at altamontenterprise.com/milestones.

Memorial contributions may be made to the Albany Center Gallery, 488 Broadway, Suite 107, Albany, NY 12207, or to St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, 140 Maple Ave., Altamont, NY 12009.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer