‘A testament to the enduring human spirit’ on display at NYS Museum

A Japanese girl who hoped for peace after Hiroshima was bombed is being honored by the New York State Museum in Albany.

Sadako Sasaki, in 1955, folded a tiny origami crane using the red wrapper of a methotrexate medicine container, a treatment for her leukemia.

In 2010, Sadako’s brother, Mashiro Sasaki, donated the crane, one of only seven remaining worldwide, to the 9/11 Tribute Museum in New York City, which in turn has given the crane to the state museum.

It is on display through October as part of a new exhibit, The World Trade Center: Rescue, Recovery, Response Gallery.

“This exhibit commemorates a young girl’s wish for peace and understanding and reminds us of our shared connections across time, geographical boundaries, and cultural differences,” said Dr. Jennifer Lemak, the chief curator of history for the museum, in a release about the exhibit.

“This important artifact,” she went on, “serves as a bridge between two profound tragedies — Hiroshima and September 11th — and offers a universal message of hope and resilience.”

Lemak is familiar to Enterprise readers because the newspaper chronicled her work with the late Emma Dickson, on the Rapp Road community, built during the Great Migration as Blacks left Mississippi and settled in the pine bush.

Lemak’s book helped get the neighborhood recognized as a New York State Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.

She is once again bridging cultures and time periods with the current exhibit.

Sadako Sasaki’s life and courage has been documented in many ways.

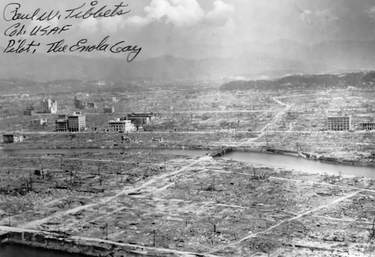

When the United States dropped its first atomic bomb on Aug. 6, 1945, Sadako’s family lived about a mile from where it fell. Sadako, who was 2 years old, was blown out of a window. She fled with her mother and brother as fires erupted across the city and black rain fell.

The family returned to Hiroshima to rebuild their lives.

“By all appearances, Sadako was a happy and healthy child,” according to an account from the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. “She was known to be a fast runner and popular with her classmates. That is why it came as such a surprise when at the age of twelve, Sadako began to show symptoms of leukemia,” a frequent result of radiation exposure.

She was hospitalized at a Red Cross hospital in Hiroshima on Feb. 21, 1955.

The Manhattan Project site continues to tell her story this way:

Sadako was very happy the day the Red Cross Youth Club gave her and the other children staying in the hospital origami cranes. Origami cranes were thought to help people who were sick become well again.

Sadako’s father, Shigeo, was visiting her at the hospital when she asked him, “Why did they send us origami cranes, Father?”

Shigeo answered Sadako’s question by telling her the Japanese legend of the crane. Japanese folklore says that a crane can live for a thousand years, and a person who folds an origami crane for each year of a crane’s life will have their wish granted.

The story of the origami cranes inspired Sadako.

She had a new passion and purpose to have her wish of being well again granted by folding one-thousand origami cranes. Sadako began collecting pieces of paper for her cranes. Sadako soon filled her room with hundreds of colorful origami cranes of all different sizes.

“After folding her thousandth crane, Sadako made her wish, to be well again. Sadly, Sadako’s wish did not come true.”

She died on Oct. 25, 1955 at the age of 12.

The account from the Manhattan Project National Historical Park goes on, “Sadako’s resilient spirit and her origami cranes inspired her friends and classmates to raise money for a monument for Sadako and the children who died as a result of atomic bombings. Since 1958, thousands have visited the statue of Sadako in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

“Sadako’s figure lifts a large paper crane overhead. Inscribed at the foot of Sadako’s statue is a plaque that reads, ‘This is our cry. This is our prayer. Peace in the world.’”

Rasul Gamzatov, the Russian poet, visited that park and was inspired by Sadako. His poem became a well-known ballad.

It was translated into English by an American poet, Leo Schwartzberg:

Cranes

Sometimes I feel that all those fallen soldiers,

Who never left the bloody battle zones,

Have not been buried to decay and molder,

But turned into white cranes that softly groan.

And thus, until these days since those bygone times

They have been flying calling us with cries.

Isn’t it why we often hear those sad chimes

And calmly freeze, while looking in the skies?

A tired flock of cranes still flies – their wings flap.

Birds glide into the twilight, roaming free.

In their formation I can see a small gap –

It might be so, that space is meant for me.

The day shall come, when in the mist of ashen

My final rest among those cranes I’ll find,

From the skies calling – in a bird-like fashion –

All those of you, who I’ll have left behind.

Sometimes I feel that all those fallen soldiers,

Who never left the bloody battle zones,

Have not been buried to decay and molder,

But turned into white cranes that softly groan …

The state museum will display Sadako Sasaki’s tiny crane each September, the release from the museum said, concluding, “It now stands as a testament to the enduring human spirit.”