Storing renewable energy raises safety concerns

The large-scale storage of renewable energy is both the law and lucrative for those building the facilities.

But, if disaster should strike, the fallout will likely be dealt with by a largely unpaid group of volunteers.

The issue was brought home this month as RIC Energy is seeking permission from the town of New Scotland to install a large-scale battery energy storage system, known as BESS, on Indian Fields Road in Feura Bush.

While national data shows serious BESS failures are rare, they pose a risk to firefighters, especially volunteer departments that may lack training and resources to deal with the unique hazards.

The state is intervening with a safety working group making recommendations to ensure the secure deployment of these systems across New York rather than just relying on developers to comply with national codes.

At the same time, it is instructive to understand the need for these large-sale battery storage systems as the state strives to meet its energy needs.

With 2030 set as the date when six gigawatts of New York state’s overall electricity capacity is due to come from renewable energy stored in large-scale batteries, the state appears, on paper at least, poised to obliterate the goal.

The rapid expansion of battery energy storage systems capacity can be traced to the state’s 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which created a mandate to reach 6,000 megawatts of stored energy by 2030.

These systems provide numerous services to the grid, including frequency regulation and peak shaving — storing energy during low-demand periods and discharging during high-demand peaks — thereby reducing reliance on fossil-fuel “peaker” plants.

The state’s aggressive policy has led to what some are calling a “speculative gold rush,” with the sheer volume of BESS applications in the New York Independent System Operator, or NYISO, interconnection queue vastly exceeding state targets.

As of late 2024, developers had submitted applications for over 30.9 gigawatts — or 30,900 megawatts — of storage, more than five times the state’s 6-gigawatt goal.

But as of January 2025, New York has approximately 430 megawatts of operational battery energy storage system capacity, with another 581 megawatts under contract. This has been supported by significant state-level investment and structured incentive programs.

The lagging build-out comes as the state faces a potential reliability issue. Over 1 gigawatt of natural-gas-fired generation has been retired in the last four years, and another 500 megawatts could come offline in 2025. This is happening as energy demand, fueled by the growing use of artificial intelligence, is projected to grow by 50 to 90 percent over the next 20 years

The 6,000-megawatt goal, double the original target set in 2018, is a cornerstone of the state’s climate agenda. The plan calls for 3,000 megawatts of bulk energy storage from projects 5 megawatts or larger, 1,500 megawatts of smaller retail storage, and 200 megawatts of residential systems.

To date, the majority of operational and planned projects are concentrated in downstate regions. High electricity demand and the goal of replacing aging “peaker” power plants have driven development in New York City and on Long Island, with major projects like the 100-megawatt East River Energy Storage System under construction in Queens and a 15-megawatt facility at the Arthur Kill Generating Station in Staten Island.

The slow build-out has been attributed to a revenue gap, where, in recent years, opportunities in New York’s wholesale energy market have fallen short of development costs, even for projects in the most lucrative regions.

The issue is compounded by rising material costs and supply-chain constraints, with front-of-the-meter projects averaging an installed cost of $645 per kilowatt-hour, compared to $524 per kilowatt-hour for bulk systems.

Front-of-the-meter means the energy-storage system is installed on the power company’s side of the electric meter, typically large-scale batteries operated by utilities. Back-of-the-meter means the storage system is installed on the customer side of the electric meter, like home batteries or commercial building storage systems. The core difference is: front is utility-controlled while back is customer-controlled.

This massive oversubscription suggests developers are securing a place in the long and expensive interconnection queue as a strategic placeholder, even if a project is not yet fully viable.

The primary bottleneck for development appears to be not a lack of interest, but the cost and timeline of the interconnection process itself.

A promising trend for future development is the repurposing of retiring fossil fuel plant sites for new battery projects, such as the facility at the Arthur Kill Generating Station on Staten Island. This strategy leverages existing grid interconnection points and is strongly supported by NYISO as a way to maintain grid reliability.

The industry is increasingly shifting toward safer battery chemistries like Lithium Iron Phosphate and adopting modular, factory-assembled designs like the Tesla Megapack that streamline construction. The proposed New Scotland project would involve five Tesla-made shipping-container-sized units — each measuring eight feet high by six feet wide and 30 feet in length.

At the same time, the state is creating new financial incentives, such as an “Index Storage Credit,” to provide revenue certainty for developers.

State leads

The summer of 2023 saw a series of fire incidents at facilities in Jefferson, Orange, and Suffolk counties. Although no injuries were reported, the fires elevated public and regulatory concern and catalyzed a swift and decisive state response.

On July 28, 2023, Governor Kathy Hochul convened a new Inter-Agency Fire Safety Working Group, bringing together relevant state agencies to examine BESS fire safety standards and develop recommendations to ensure the safe and secure deployment of these systems across New York. The state’s proactive approach marked a shift from relying on developers to comply with national codes.

The committee’s robust recommendations, which are now being incorporated into state funding requirements, include mandatory peer review, explosion control, emergency response and training, enhanced monitoring and support, and improved signage and security.

This will inevitably lead to a high rate of project attrition and creates a fiercely competitive environment for the limited number of state contracts, favoring well-capitalized developers who can afford the risk and the wait.

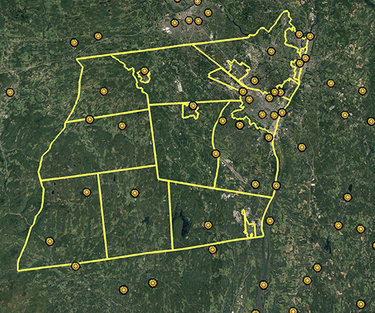

Upstate New York is also seeing significant investment, including Key Capture Energy’s 20-megawatt facility at the Luther Forest Technology Campus in Saratoga County and the state’s first utility-owned facility, a 20-megawatt project in Franklin County that became operational in 2023.

The deployment is supported by more than $1.2 billion in state funding, primarily administered by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, or NYSERDA. The agency’s incentive programs are geographically varied, offering a higher rate per kilowatt-hour for projects in disadvantaged areas.

Boots on the ground

As developers like RIC Energy propose large-scale battery-storage facilities in towns across New York, like New Scotland, local planning boards and volunteer fire departments are grappling with a new and complex set of safety, regulatory, and technological challenges that are fundamentally different from those posed by solar farms.

While solar proposals focus on land use, visual impact, and farmland preservation, discussions about battery-energy storage systems shift almost entirely to fire safety, emergency response plans, and the science of thermal runaway.

This heightened public scrutiny and regulatory complexity often extends project timelines from a typical 6 to 12 months for solar to 12 to 18 months for a battery facility.

As the proliferation of large-scale battery storage facilities continues across New York, local officials and volunteer fire departments are raising alarms over the unique and serious fire risks posed by the technology, prompting a state-level push for stricter safety codes.

Concerns have been voiced in communities like Ulster County, where residents protesting a proposed 250-megawatt facility said it was “inviting disaster.” In other parts of the state, such as Raquette Lake, towns have imposed moratoria on new battery projects following high-profile incidents like a four-day lithium-ion battery fire in nearby Lyme.

The primary hazard is a phenomenon known as thermal runaway, where an overheated battery cell can violently vent and ignite adjacent cells in a cascading fire that is notoriously difficult to extinguish. Responding fire crews must contend with intense heat, the risk of re-ignition, and the release of toxic gases like hydrogen fluoride.

The consequences of a thermal runaway event are multifaceted:

— Intense and persistent fire: BESS fires generate extreme heat and are tough to put out with conventional methods. The stored energy continues to fuel the reaction, and fires can reignite for hours or even days;

— Flammable gas production: Failing battery cells vent flammable gases, including hydrogen and methane, which can accumulate inside an enclosure and lead to a violent explosion if ignited; and

— Toxic gas release: The reaction also releases a cocktail of highly toxic gases, most notably hydrogen fluoride, a corrosive and poisonous substance that poses a significant respiratory hazard to firefighters and a potential environmental risk to the surrounding community.

While national data shows serious BESS failures are rare, fire chiefs acknowledge that the technology creates unorthodox hazards. For the volunteer and career fire crews who must respond, knowing a site’s layout, vent locations, and shutdown protocols is considered vital to staying safe.

This unique fire behavior has forced a fundamental shift in firefighting tactics. The primary strategy is not extinguishing but cooling.

Emergency plans advise a defensive “let it burn” approach, where firefighters apply massive volumes of water to the exterior of adjacent, uninvolved battery units to prevent the fire from spreading, while the initial unit burns itself out.

This presents a challenge for the volunteer fire departments that constitute the vast majority of New York’s fire service and are often the first to arrive at incidents in the rural and suburban areas where many of these facilities are being sited.

These departments often face budget and training constraints and may lack the hydrant infrastructure needed for the sustained, high-volume water flow required for cooling a multi-megawatt battery system.

Experts have identified a significant “training and equipment gap,” noting many smaller volunteer units with limited budgets are not yet adequately equipped or trained for the complex chemical reactions and electrical hazards of a battery fire.

To bridge the knowledge gap, state agencies have begun to roll out new training resources. The state’s Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services now offers a specific “Battery Emergencies and Electrical Storage Systems Training Program” for first responders and has published a response guide.

NYSERDA also hosts regular webinars for local governments and first responders.

However, while the Firemen’s Association of the State of New York provides a wide range of training for its members, specific courses on battery storage incidents are not yet prominent in its publicly listed catalogs, indicating a potential area for future curriculum development.

Recommendations

In February 2024, the state-level working group released its recommendations for updating the Fire Code of New York State. The proposals, which apply to lithium-ion battery energy storage systems larger than 600 kilowatt-hours, are now being incorporated into NYSERDA’s funding requirements, making them mandatory for new projects seeking state support.

While the working group proposed a comprehensive slate of updates to the state’s fire code, its report also detailed several important safety topics that may require action outside of direct code changes.

The formal recommendations from the governor’s Inter-Agency Fire Safety Working Group are now before the State Code Council for consideration. The proposed rules would specifically target lithium-ion battery energy storage systems that exceed a 600-kilowatt-hour capacity and would apply statewide, with the exception of New York City, which has its own fire code.

The report details numerous proposed changes to existing fire code provisions to address identified safety gaps.

One key recommendation would make independent peer reviews mandatory for all large-scale battery installations. Currently, requiring such a review is at the discretion of the local code-enforcement official, an authority that is rarely used.

Under the proposal, NYSERDA would establish a list of approved peer reviewers and offer no-cost reviews for projects receiving state incentives. The group also recommended expanding the requirement for explosion-control systems to include sealed battery “cabinets” in addition to the currently covered rooms and walk-in units.

Other proposed updates would mandate that, for any battery fire, qualified “hazard support personnel” must be able to arrive on-site within four hours to support local first responders.

The rules would also require that all facilities be monitored 24/7 by a staffed Network Operations Center that can immediately relay critical failure notifications.

Significantly, the working group recommended removing the current fire code exemption for projects owned or operated by electrical utilities, a change that would ensure all battery storage facilities, regardless of ownership, comply with the same safety standards.

In addition to updating existing codes, the working group proposed several new standards for inclusion in the state fire code.

The report strongly recommends a new requirement for a site-specific emergency response plan for every facility, which must be developed in consultation with the local fire department. To complement this, battery operators would be required to offer annual, site-specific training to those same local fire departments.

The group identified a need to require that equipment manufacturers disclose the “root cause analysis” after a fire to state and local authorities to promote continuous safety improvements.

Further discussion was also recommended on enhancing guidance for firefighting water supply at battery facilities, as well as establishing safe clearance distances between the battery systems and oil-insulated transformers, which could worsen a fire.

On top of these existing strains, first responders must now prepare for the unique behavior of lithium-ion battery fires, which are difficult to extinguish with traditional methods and carry a high risk of re-ignition. This requires specialized training in new defensive tactics — such as cooling adjacent battery modules to let the initial fire burn out — and specialized equipment like thermal-imaging cameras.

The state working group’s report stresses that an effective response depends on pre-incident planning, requiring developers and operators to work closely with local fire departments from the earliest stages of a project to review site plans and establish emergency access protocols.

A new provision for mandatory, industry-funded “special inspections” is also recommended. These inspections would occur at a regular cadence throughout a project’s life and be conducted by specialized, third-party experts to ensure ongoing safety and compliance.