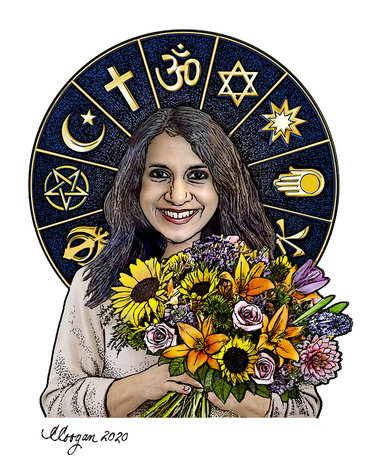

Embracing a common humanity: A lot of different flowers make a bouquet

Fazana Saleem-Ismail was a woman of quiet courage and great caring.

She died on June 25 of stomach cancer. She was 47.

We met Fazana when we wrote about a charity she had founded in 2011, the year she moved to Guilderland, to give birthday parties for homeless children. She named Jazzy Sun Birthdays after the nicknames of her son, Jazzib, and daughter, Sanari.

Her reward, she told us, was the joy she saw in the children she celebrated, children who otherwise might not have a party, might not feel like a star on their special days the way her own children did.

Fazana harnessed the energy of volunteers, like Scout troops or church groups, to create the festivities, which, in turn, helped those volunteers as well.

“Parents say it’s hard to explain the concept of poverty to their children,” Fazana said. “A birthday is something all kids can relate to.”

She said of poverty, “It becomes a lot more real when they help with these parties. Parents are often nervous, not sure they want their children to play with homeless children.” But then they come to the party, she said, and both parents and children realize, “These kids are just like them.”

Over the years, again and again, that was a lesson we learned from Fazana. A social scientist who worked for the Research Foundation of The State University of New York, she found the humanity in each of us and let others see it, too. She did not let labels, or stereotypes, separate us, one from another.

Fazana was deeply committed to her religion, Islam. Her parents had immigrated to the United States from Sri Lanka in the 1970s and Fazana grew up on Staten Island, describing herself on college applications as a Muslim girl who who worked at a Jewish community center and went to Catholic school. After graduating from Bryn Mawr College, where she had led both the Muslim and international student associations, Fazana said she “clicked” with with Jiffry Ismail, a Muslim man from Sri Lanka her family had settled on for her marriage.

In Guilderland, Fazana became a well-known voice for Islam, speaking to both educate and enlighten.

In 2016, the day after Omar Mateen had opened fire in a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, killing 50 people, Fazana started a session at the Guilderland library by reading a solemn statement about her horror to learn that the killer was someone who was supposed to be a Muslim. “Omar Mateen does not represent us,” she said.

She quoted from the Qur’an: “Whoever kills a human being, it is as if he killed all of mankind.” She then led the group in observing a moment of silence for those who had been killed.

During the panel discussion that followed, in which a curious crowd learned about Islam from three Muslim women, Fazana displayed a book her daughter had made when she was in second grade, describing, in the painstaking hand of a child learning to write, the celebration of Ramadan.

When her 7-year-old came home from school that day, “She was sad. Nobody had clapped for her,” Fazana said, the way they had for her classmates who had shared their more familiar traditions of Christmas and Hanukkah.

Three years later, at age 10, Fazana’s daughter told her mother why she had been so sad that day. One of her classmates had asked her, “Are your parents bad? Do they do bad things?”

“If a 7-year-old boy is asking that, he’s learning that at home,” Fazana said. Nevertheless, her daughter and the boy became friends. “He knows who I am,” her daughter said.

She became a flesh-and-blood person to him, not an evil stereotype.

“Even our Prophet … when he was maligned,” said Fazana, “he always treated people with kindness. My message to my children is always: Be an example.”

And so she was.

Certainly, in her many visits to churches and community groups, Fazana informed people about the particulars of her religion. She encouraged people to question her, telling them no question was stupid.

She showed an app on her cell phone, programmed with a call to prayers. She said prayers before sunrise, around noon, in the late afternoon, at sunset, and at night. “The purpose is for us always to be God-conscious,” Fazana said.

She highlighted some of the misconceptions about Muslims to set the record straight. “We worship the same God as Christians,” she said. “We believe in all the prophets … Jesus as well.” Jesus is mentioned in the Qur’an 93 times, she said, and an entire chapter is devoted to his mother, Mary. “There’s more about Mary in the Qur’an than in the Bible,” she said. “We greatly respect the prophets but don’t pray to them.”

Fazana faulted the media for widespread misunderstanding of the term “jihad.” “‘Jihad’ means to strive with all one’s might,” she said. “‘Jihad is not going to war with other people … The highest form of jihad is spiritual.”

Fazana also said there is a widespread misconception that Islam oppresses women. “Religion and culture get mixed up,” she said. Muslim women since the 1400s, had been allowed to own property and businesses, receive an inheritance, get an education, participate in legal affairs, and vote, she said, while those are more newly-won rights in the United States.

But Fazana did much more than just educate others about the particulars of her religion.

As Donald Trump campaigned for the presidency, hatred towards Muslims and others ratcheted up. After Trump won the November 2016 election, Fazana, working with the Capital District Coalition Against Islamophobia, hosted an Albany rally the same day as a victory rally was held by the Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina.

“When one community is targeted, we are all targeted; we are all part of humanity…There is power in numbers,” Fazana said of her reasons for organizing the rally.

“That we have a president-elect who was endorsed by a former leader of the Ku Klux Klan is frightening, and so is having white supremacists among his appointments,” Fazana told us. “We believe our strength comes from our diversity.”

The Albany rally on a blustery December day was diverse indeed. Hundreds of people — young and old, Black and white and Asian, gay and straight, Christian ministers, Jewish rabbis, Muslims, and a Quaker poet — listened as Fazana asked at the start of the rally, “Can you feel the love?”

“Yeah!” roared the crowd in return.

“We today are building a movement … to work against forces of hate,” said Fazana.

While Fazana moved a crowd that day, much of her movement was more individual — but still based on love. “I’m a firm believer in the power of personal connections to break down barriers and build bridges to promote unity,” she said.

Fazana was a warm and vibrant woman with a smile that engaged friends and strangers alike. She made immediate personal connections and set the stage for others to do the same.

Last year, for example, she set the stage by starting an International Night at Lynnwood Elementary School, where her son was a student. Two-hundred people turned out to get their “passports” stamped as they “visited” 11 countries, each with food to sample and activities to try.

Fazana teared up to see how much love and effort the families representing their countries put into their displays. “I’m a firm believer in having children embrace diversity as young as possible,” she said.

Fazana did not shy away from the difficult. In February 2017, the day after six Muslims were killed by a terrorist in a Quebec mosque, the Methodist church in Voorheesville was filled with people who came to hear Fazana talk about her religion. As always, she focused on the things we, as human beings, have in common.

A man in the audience became physically aggressive and shouted, “You people have to leave. You’re ruining our country.” After he left, Fazana continued her talk then headed home with her two children — her daughter was then 12 and her son was 7.

“They were scared,” she told us, and it was the most scared she had been. She worried about her family’s safety as well as her own. But then she reasoned, “Instilling fear in people is a tactic to shut down diversity. I can’t fall prey to that.”

Fazana did not fall prey to fear. She carried on.

We are profoundly sad that she has died. But we feel sure she moved others just as she did us and, in that way, her work on earth will carry on.

We remember how she quoted the Qur’an, saying, had God willed, He could have made one community. Rather, He made diverse communities so they would compete with others in good works.

“God wanted us to be different,” Fazana said. “We’re your sisters in humanity.”

We will remember those words as we strive, just as Fazana Saleem-Ismail did, to appreciate the differences in people while finding a common humanity.