Let’s lift a light beside the golden door

A week ago, a friend of ours took part in Albany’s Pride parade. She spoke of how happy and together people felt that day. Gay men and lesbian women who had struggled so long and hard for acceptance could march in a parade, waving a flag of many colors, a symbol of their pride. And people cheered.

Then came news of the massacre in Orlando — 49 killed in a gay nightclub, 53 more wounded. A fragile sense of hard-won acceptance was shattered.

The next evening, we went to hear three Muslim women at the Guilderland library talk about their faith and their lives to a packed hall of curious and supportive onlookers. The event, planned months ago, took on new meaning since the Orlando gunman, a 29-year-old American man, Omar Mateen, was Muslim.

The women stressed how theirs was a religion of peace. “Omar Mateen does not represent us,” said Fazana Saleem-Ismail. She quoted from the Qu’ran, the Islamic sacred book, believed by Muslims to be the word of God as dictated to Muhammad: “Whoever kills a human being, it is as if he killed all of mankind.”

When someone in the crowd asked why so many violent acts, like the one in Orlando, were perpetrated by Muslims, Amina el-Sheikh, a nurse and mother, answered with directness, striking at the heart of the matter. She said simply that he was mentally ill.

We ran a picture of the Muslim women and their stories on our front page last week just as, in recent weeks, we’ve run the stories of transgender students on our front page, and in years past we ran the stories of gay students coming out on our pages.

We are part of a community rich in diversity. We may not be able to prevent acts of hatred or terror in other places, but we can work — all of us — to prevent them here.

We can make an effort to know our neighbors — the gay and the straight; the Jews, the Christians, the Muslims, the Buddhists, the atheists; the rich and the poor; the old and the young. The library panel was a start, a toehold, on a mountain we must all climb together.

In the aftermath of the Orlando shooting, we read a Facebook post by Brian Alvear, whose sister was killed at the Pulse nightclub.

Alvear wrote with fierce passion the same thing that El-Sheikh had spoken to the library crowd in calmness. “Listen I know a lot is happening and this a horrible thing and my family is dealing with it first hand, but don't you f---ing dare blame this on a group of people,” Alvear wrote. “This was 1 sick mother f---er. Don't blame anything but that.”

It is wrong to condemn a group for the act of one; it is wrong to foster hatred based on stereotype. That Alvear could see this in the midst of great national confusion and great personal grief should inspire us all.

Symbols, like the rainbow flag, can be a source of pride and strength. Symbols can also make people into targets. Two of the Muslim women speaking in Guilderland last Monday night wear a hijab or headscarf, and have suffered harassment because of it.

El-Sheikh said she wears a headscarf “because my religion says, guard your modesty.” She confided that she had been kicked out of a patient’s room because of her headscarf. It hurt her feelings but, when she was asked back in, she provided good care.

Safiyyan Stewart, a college student, said that, when she was in high school, “I was bullied because of my hijab.”

El-Sheikh said it is hard on her eldest daughter wearing a headscarf to school. “But she does push through; it comes from her heart,” she said.

If we witness acts of unkindness toward women wearing a hijab — or anyone being tormented for being different — we need to speak out and intervene.

It’s particularly hard now on Muslim women because the symbol of their faith, their headscarves, are so visible. Rhetoric from Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, calling for barring Muslims from the country, has made the harassment worse. “It gives the average person license to say negative things about Muslims…if the person who could be our next president is saying that…,” said Saleem-Ismail, speaking at the library.

We were inspired by another Facebook post last week, written by a young Muslim woman, Amaira Hasan, about riding the subway, as she does each weekday, from Queens to her job in Manhattan.

“Just now, on my way to work, a man got on my train yelling as he came onto an incredibly packed train for the ‘two terrorist foreigners to go back to where they came from.’ These two ‘terrorist foreigners’ were two (understandably terrified) hijabi Muslim women,” she wrote.

“Before I could say anything, the entire train erupted in anger. A black man, a Romanian, a gay man, a bunch of Asians, and a score of others came to their defense demanding that this man leave these women alone and get off this train. The man insisted that the two women go back home and take their bombs with them.

“After some back and forth, one man said, ‘This is New York City. The most diverse place in the world. And in New York, we protect our own and we don't give a f--k what anyone looks like or who they love, or any of those things. It's time for you to leave these women alone, Sir.’

“I couldn't have said it better. Sure enough, our train was stopped. This royal douche got off the train to the sound of cheering.

“I say all this to say that in light of all the bad happening around us, remember that there's so much good and so much love.”

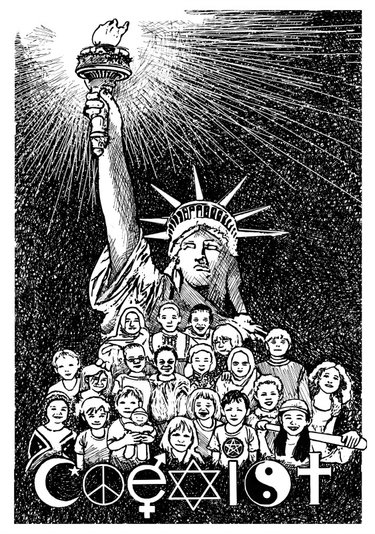

We are proud to come from New York, a diverse place that has, as perhaps its preeminent symbol, the Statue of Liberty, a beacon welcoming generations of immigrants to our shores — “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” — diverse people who have made our nation richer and stronger.

Two Muslim men, both scientists, at the Guilderland library event spoke of how accommodating bosses and co-workers had been in finding time and space for their five daily prayers.

“For every one person hating you,” said Abdul Jabbar, “thousands of Americans want to embrace you.”

Let’s have the moxie of the New York subway riders and continue to accept and stand up for those who may be different than ourselves.

Saleem-Ismail may have said it best when she quoted from the Qu’ran, saying, had God willed, He could have made one community. Rather, He made diverse communities so they would compete with others in good works.

“God wanted us to be different,” said Saleem-Ismail. “We’re your sisters in humanity.”

— Melissa Hale-Spencer