GCSD proposes $105M budget, includes diversity administrator

— Graph from the Guilderland Central School District budget presentation

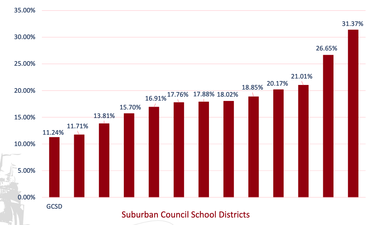

Based on 2019 figures, Guilderland’s fund balance as a percentage of its budget is the lowest among Suburban Council schools. The budget proposed for next year puts the bulk of added aid into the district’s fund balance or rainy-day account.

GUILDERLAND — After a lengthy and stunningly frank conversation about racism in the Guilderland schools, the school board here added a full-time post for an administrator who will oversee diversity, equity, and inclusion in the district.

The decision capped an April 13 budget discussion, which ended in a 7-to-1 vote to adopt a $104,979,570 spending plan for next year. Barbara Fraterrigo cast the dissenting vote.

Voters will decide on the budget on May 18.

At the same time, school district residents will elect three board members to serve three-year unpaid terms. Incumbents Seema Rivera, Blanca Gonzalez-Parker, and Luciano Alonzi are being challenged by Nathan Sabourin.

A simple majority vote is needed for the budget to pass since the spending plan comes just up to the state-set levy limit, at $75.9 million, without exceeding it.

The tax rate for Guilderland residents is estimated at $17.32 per $1,000 of assessed property value, which is up about 22 cents from this year’s rate.

The proposed budget represents a 1.89-percent increase over this year’s spending plan.

Addressing racism

“With the exception of a few leaders, there is a lack of strong leadership in addressing racism,” said Seema Rivera, the first woman of color to lead the Guilderland School Board, in written comments to the board.

“There are many articles and letters written in The Altamont Enterprise in the summer of 2020 addressing the change that was coming, and there is no doubt this work is challenging,” she said. “However, there was an understanding that we would need to be strong in the face of pushback.”

After decades of incidents of racial discrimination at Guilderland — several of which came to public notice when lawsuits were filed — school board members at their July 1 meeting were passionate about pursuing changes in curriculum, policy, and staff training and recruitment.

“If we do not seize this moment to make real changes, shame on all of us,” said Superintendent Marie Wiles at the time.

Several Black Guilderland alumnae, in the wake of George Floyd’s death, had had a phone conversation with school board members. The women expressed their anger and frustration over the school’s curriculum. “They didn’t know about their own history; just the white version of history,” said Wiles at the time. They did not know what their peers in college had been taught, and they frequently used the term “white-washed curriculum” to describe what they had been taught at Guilderland.

Subsequently, the board appointed a committee to look at and deal with equity issues.

The board held its April 13 meeting as Derek Chauvin was being tried for Floyd’s murder, before the guitly verdicts were reached.

“In response to questions we are now receiving about the importance of this work, I ask, how many incidents have to take place until the Guilderland school district starts to be proactive … beyond performative activism?” Rivera went on. “The district needs to ask itself — Why is the existence of this work perceived as a threat?”

Rivera concluded, “In a speech from Toni Morrison in 1975, she talks about racism and how it distracts you from doing your work … let’s stop being distracted and start doing the work.”

The original draft of the 2021-22 budget included an assistant-principal post, three-tenths of which would be devoted to equity issues.

“If you are asking for a diversity educator, are you racially profiling the position?” asked long-time board member Barbara Fraterrigo.

She recommended not “pigeon-holing” the new assistant principal.

Wiles responded, referring to Amy Hawrylchak, who left her assistant-principal post at Guilderland High School to become principal of Tech Valley High School, “I think Dr. Hawrylchak was the inspiration for this because she very much blended the two roles really beautifully.”

“Barb, what did you mean by racial profiling?” Rivera asked Fraterrigo.

“Are you basically just looking for a person of color or are you looking for the most qualified person,” Fraterrgo said people had asked her.

Fraterrigo went on, “I think we have to show with our equity audit … our district is in arrears and our teachers are diversifying their teaching style enough to accommodate the needs of the poor, the English language learners, the person of color.”

Wiles said she didn’t think about the position in terms of racial profiling. “This is a position where we want someone to focus on equity in all of its forms …,” she said. “How do we serve each and every student where he or she is?”

“There’s no priority for race?” asked Rivera.

“We have a priority in all of our hiring to create a more diverse workforce ...,” Wiles responded. “But in the end, we need to hire the people who can best meet the needs of the district.”

She said the new hire would work with the committee, made up of volunteers, “so things don’t fall through the cracks.”

“A racial epithet was said to a student and then we’re sitting here, like, yeah, we’re doing a great job,” said Rivera. “No, we’re not doing a great job.”

She also said of Hawrylchak, “She’s not here anymore. You can’t depend on one person.” Rivera said she hoped somebody from the top would send “this message down and get things going.”

Rivera went on, “Board members have left disappointed with the weak motions, weak decisions that the district has made …. I’m being asked by the district office to, you know, be polite to people who are being disrespectful and racist to me and to probably other people in the district and then I see no support from up above.”

“How can we be sure that the administration or the district that has been called out or accused of being racist in the past, that they’re going to be able to hire someone for the diversity-inclusion position unless it’s really defined really well?” asked board member Gonzalez-Parker.

Wiles said board members would be included on the interview committee and their perspectives were welcome.

Board member Kelly Person read from a recently released State Education Department policy in which the Board of Regents expressed “its expectation that all school districts will develop policies that advance diversity, equity, and inclusion, and that they implement such policies with fidelity and urgency.”

As the board discussed making the new post full-time rather than part of the new assistant principal’s job, Wiles recommended the $113,800 for salary and benefits could come from reducing the pool for unassigned teaching positions, which are used as needs unfold.

“My problem is we haven’t demonstrated a need for a full-time position ...,” said Fraterrigo. “To me, the needs for an additional social worker … [are] far more important at this point in time.”

“I feel like it falls inline with mental-health needs,” responded Rivera. “I don’t think they’re separate. I also think it falls in line with the board goals and the superintendent goals. Dr. Wiles, in your opinion, is this a position the district needs?”

“The short answer is yes,” Wiles responded, explaining that, before the district was allocated additional aid, “it was all about striking a balance.”

She noted the newly released State Education Department document has “a huge focus on climate and culture within our buildings, which is a huge part of the work we need to do.”

Wiles went on, “Equity work is not just about serving our children of color but it’s really looking across all those categories of children who may not feel as well supported as they could … our students in poverty, our LGBTQ community, our students with disabilities.”

“We value this as a community,” said Person.

Alfonzi said he was not against creating the position but was concerned about where the money was coming from and about not following the priorities expressed by the public through an online ThoughtExchange in which smaller classes and fewer administrators were the top priorities.

He noted this would add an administrator while the public feels the administration is top heavy.

“Just because something’s said doesn’t make it true,” said the board’s vice president, Gloria Towle-Hilt of the district being heavy with administrators.

Board member Benjamin Goes said of school board members, “We’re still representatives of the community … We ask them because it guides our actions,” he said of public opinion.

“I think the public should inform us, absolutely,” said Towle-Hilt. “But we also have a responsibility that we were elected by them to do our own duty and make sure that we are informed.”

In the end, the budget amendment to create a full-time post for a diversity, equity, and inclusion administrator passed, 5 to 3. Rivera, Rebecca Butterfield, Towle-Hilt, Gonzalez-Parker, and Person voted in favor. Fraterrigo, Goes, and Alfonzi were opposed.

Budget

Superintendent Wiles on April 13 described the aid picture as 180-degrees different than when the school spending plan was first drafted in March, based on Governor Andrew Cuomo’s executive budget.

The vast majority of the unexpected aid will go into the district’s fund balance or rainy-day account.

Assistant Superintendent for Business Neil Sanders said of the state budget, “This budget is historic in terms of the amount of aid to education and we should not assume that that historic rate will continue.”

About a quarter of the Guilderland budget is typically funded by state aid. Guilderland next year will get about $2 million more in state aid than it had been allocated in the executive budget.

“Our total state aid is going from $25.1 million to $27.2 million,” said Sanders, terming it “a significant increase for the school district.”

The state legislature this year adopted a plan to restore Foundation Aid to schools, which was a long time coming.

In 1993, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity argued successfully in court that some students were being deprived of the constitutional right to a sound basic education due to inadequate state funding.

Foundation Aid will be restored over three years. Guilderland was owed $20.9 million and will receive $15 million for next year. The remaining $5.8 million is to be phased in over the following two years.

“We hope the state will continue to meet its obligation in the remaining two years,” said Sanders.

Additionally, Guilderland has been allocated $626,400 for pre-kindergarten, which it hasn’t offered before.

“We were surprised when we got our allocation,” said Sanders, noting there is no clear guidance yet from the State Education Department on how the money is to be spent. The legislation provides funding only for two years: 2021-22 and 2022-23.

To get full funding, a class would have to have 18 to 20 students, Sanders said. Some of the challenges the district would face, were it to launch a pre-kindergarten program, would be finding space in school buildings and providing transportation.

He said Guilderland could partner with an outside agency, which could provide space and a program under the district’s oversight.

Importantly, federal aid is now separate from state aid. “They’re not tied together anymore as they were under the original executive budget proposal,” Sanders noted. The state’s local funding reduction of about $4 million for Guilderland was eliminated in the adopted state budget.

In federal aid, Guilderland is getting $4.6 million from Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, to cover expenses from March 13, 2020, at the start of the pandemic, to Sept. 30, 2022.

From the American Rescue Plan, Guilderland is being allocated $2.8 million to cover the period from March 13, 2020 to Sept. 30, 2023.

Both of these federal funds must be applied for and are not part of the adopted budget proposal for next year.

Allowable uses for the federal funds include addressing learning lost during the pandemic; providing mental-health supports for students; after-school and summer learning programs; activities to help low-income students and students with disabilities, English learners, racial and ethic minorities, homeless students, and foster-care youth; hardware and software for remote or hybrid learning; purchasing cleaning supplies or personal protective equipment; air quality and ventilation improvements; improving preparedness efforts and coordination; and planning for school closures.

“These funds do run out,” said Wiles, indicating the federal funds would be used for non-recurring costs.

The budget draft, which the board ultimately adopted, put the vast majority of funds not available under the executive budget into Guilderland’s fund balance. Just $84,000 is earmarked for expanded instructional coaching.

Sanders displayed a graph, showing that Guilderland, among the 13 Suburban Council schools, has the lowest percentage of fund balance.

“We have the least amount of savings,” said Sanders.

He went on, “On the revenue side … we would look to reduce our appropriated fund balance and reserves by $988,672 so that we have almost $1 million for taking from our savings to fund the budget. We have an opportunity here to basically eliminate that so we would be back in balance with our budget, which means we’re not constantly drawing from our savings to fund our expenses.”

Sanders stressed, “The goal is to put us in a better position financially for years to come ...We won’t need to use any of our savings to have a balanced budget.”

Gonzalez-Parker said, “This seems to me like it’s a unique year, a year where folks have lost their jobs and I don’t see the budget or the district reflecting us being particularly frugal.”

Later in the meeting, board member Goes said, “It’s unclear to me why we would be going up to our tax cap with $630,000 of unassigned FTEs sitting in our budget.” He was referring to teaching posts — full-time equivalents — that would be filled as needed.

He also referenced the declining enrollment at the high school, resulting in a budget cut of 1.7 posts. “I really feel like we need to give that back to the community,” said Goes.

Late in the meeting, just before the budget adoption, Goes proposed an amendment that, with attrition at the high school, the remaining FTEs be cut. The motion did not carry with four members voting for it: Goes, Towle-Hilt, Alonzi, and Gonzalez-Parker — and four voting against: Rivera, Butterfield, Person, and Fraterrigo.

Sanders said that, if the added state aid were used to lower taxes, “That could just end up putting us back in a position where we have no flexibility going forward should state aid not continue to increase.”

Were that to happen, he said, “We’re looking at reductions, larger class sizes, less opportunities for kids. Kids deserve better than that. They should have to follow the whims of an economic cycle to determine the quality of an education that they receive … This proposal is just prudent, sound fiscal management.”

During the meeting, some board members expressed frustration with their role in the budget process.

“We’re voting on things without details … We’re not really getting clear answers ...,” said Rivera. “So it’s almost like, you know, a dog-and-pony show when it’s being streamed to the public.”

Towle-Hilt responded that school leaders had been “very fair in terms of being here to give information.” She said, “If it’s not sufficient, then we ask another question or figure it out …. In the end, we decide.”