Resolve the salt-shed standoff for the public good

Governments provide needed public services — services paid for with public funds.

So the pressure to use these funds efficiently is understandable.

That’s part of what propelled the current federal administration to office — a belief that our government could cost less and be more efficient.

We’re a local newspaper so we’re not going to focus on the melee of random slashing being done by our federal government in the name of common sense.

Rather, we’re going to focus on one distressing example of government partnership gone awry.

The partnership, between Albany County and the town of Knox, was intended to be a cost-saving measure that would help provide an essential public service.

Common sense tells us that keeping roads safe for winter travel is an important government function.

Anyone who reads our Back In Time column each week knows that, a century ago, a snowstorm could shut down life in the Hilltowns — commerce, education, church-going, medical attention, and more — for days or even weeks.

Now we count on government workers at the state, county, and town and village levels to keep our roads navigable in wintertime.

Although we’ve written on this page about environmental concerns with the use of road salt, we recognize rock salt is widely and effectively used by our county and town highway departments.

Knox and Albany County have shared a salt shed at the county’s highway department on Township Road in Knox. This seemed to us like good common sense.

Over decades, we’ve written many times on this page on the value of governments sharing services. One example are the Boards of Cooperative Educational Services our state legislature created in 1948 so that school districts — particularly small, rural districts — could provide services they wouldn’t otherwise be able to offer. For instance, a single Latin teacher could be hired to teach at several different schools.

This sharing not only provides services that might otherwise be unavailable but also makes them more efficient and economical. BOCES, of course, has greatly expanded and now has 37 regional centers.

In 2008, we wrote about the very first report that mapped shared services in Albany County. That report, by the Intergovernmental Studies Program at the University of Albany’s Rockefeller College, found that the less active collaborators tended to be municipalities with fewer than 10,000 residents.

The report also reached a counterintuitive conclusion: Municipalities with fewer funds were far less likely to share services than those with more. In the Enterprise coverage area, Guilderland, a large suburban town, had the most shared-services agreements while the rural Hilltowns had the least.

The Rockefeller College report found that residents often don’t trust other municipal governments, creating a challenge to brokering cooperative agreements.

“Nearly half of the Albany County leaders we interviewed observed this tendency toward provincialism is a serious hurdle they face in proposing shared service agreements,” said the report.

That report was released in the midst of the Great Recession.

A decade later, then-Governor Andrew Cuomo required each of the state’s 57 counties outside of New York City to come up with plans for consolidating municipal services.

The goal was to lower property taxes by cutting local government costs; the mandate was enacted as part of the state’s 2018 budget.

We interviewed leaders in each of the towns we cover and learned that the larger towns, Guilderland and New Scotland, were enthusiastic about shared services: “We do a tremendous amount of shared services in town-to-town interactions and county interactions. We’re doing a lot … and it’s worth looking into further,” said New Scotland Supervisor Douglas LaGrange in 2018.

“We do a lot of shared services already,” said Guilderland Supervisor Peter Barber. Guilderland’s highway superintendent in 2018, Steven Oliver, said his non-union department was able to assist unionized departments by operating according to their rules.

At the same time, Hilltown leaders were wary they would lose independence and control.

“It’s definitely not a good idea, and the town residents are going to suffer for it,” said Berne Highway Superintendent Randy Bashwinger at the time.

Bashwinger said there were too many factors keeping consolidation from working efficiently. Berne’s highway department operates under a different union — the United Public Service Employees Union — than the county — which uses the Civil Service Employees Association — he said, and it uses a different payscale.

The difference between county-maintained roads and town-maintained roads also means the town uses different materials to treat its roads, with stone sand or stone mixed with road salt to prevent erosion on Berne’s 38 dirt roads. Pure salt, used by the county, “eats the dirt away,” said Bashwinger.

“There’s just so many variables that would not work for the town,” he said.

Consolidation of course is different from sharing services. With consolidation, one entity subsumes another.

Vasilios Lefkaditis, then the supervisor of Knox, said in 2018 that shared services were not being considered by Knox.

“I’m not interested in our roads taking second fiddle to, you know, county and state roads,” said Lefkaditis. “Are they going to plow Route 20 faster, or are they going to plow a dirt road in Knox?”

One of the few instances of sharing that came out of that initiative was the salt shed in Knox.

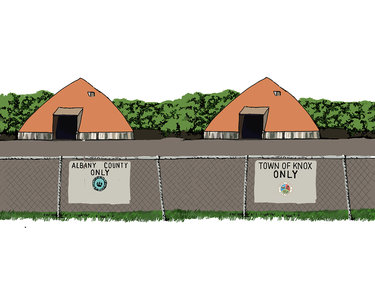

We would like to point to it as a symbol of how municipalities working together can save taxpayers money. But it has gone horribly awry.

Just after covering the New Year’s Day re-organizational meeting in Knox this year, we got a call from a man who did not identify himself, saying there were problems at the salt shed.

Our Hilltown reporter, Noah Zweifel, looked into it and learned that Knox was planning to build its own salt shed after running into conflicts with Albany County.

Knox Supervisor Russ Pokorny said the town and county track the amount of salt used differently, so it’s hard to reconcile the numbers.

It’s also inconvenient for the town to have to coordinate pickups with the county, Pokorny said, and to make the trip to fill town trucks. “The guys kind of reached the end of their rope … and they finally just concluded … that we really need to go our own way because we can’t seem to keep this straight anymore.”

On March 18, the county’s lawyer sent a letter to the town claiming that Knox used more than 300 tons of its road salt over the last two winters without permission and demanded $18,000 as repayment. The letter said that, if Knox failed to pay within seven days, the county would deduct the $18,000 from the town’s sales-tax disbursement.

County sales tax, distributed to towns on the basis of population, is Knox’s major revenue source.

Pokorny responded through The Enterprise, “We feel like the problem is accounting, and as a matter of fact we put $17,000 worth of salt in the shed between December and January … That’s about half a year’s use, so I don’t know how we could possibly be missing 300 tons. That seems absurd.”

What we find absurd is that these two governments — each elected to serve the people — cannot work this out.

This week, Zweifel reports that Knox has hired its own lawyer, at $250 an hour, to contest the payment and the county has forbidden the town from using its shed to store salt.

Building a new, town-owned shed would be convenient, Pokorny said, but expensive — somewhere between $50,000 and $60,000, according to recent bids.

The public, of course, are the losers in all this no matter which side “wins.” Taxes are paying for lawyers on both sides. And Knox, with a yearly budget of roughly $3 million, is faced not just with an $18,000 repayment but with building a new shed for $50,000 or more.

A report on municipal cooperation put out by the office of the state comptroller might make worthwhile reading for both parties.

“There is clearly a potential for cost savings through economies of scale and combining functions ….,” says the report. “By maximizing available resources through the use of cooperation agreements, local governments can realize many benefits.”

The report lists potential barriers to intermunicipal cooperation and outlines ways to surmount them.

“Sometimes,” it says, “a simple lack of trust between the potential partnering communities can stand in the way of cooperation efforts. This may be brought on by a perception that one community will be taken advantage of, or that the plan itself fails to bring about a win/win outcome. Personalities and disputes between local officials in neighboring communities can hamper cooperation efforts as well …. Inexperience and a lack of legal knowledge also threaten cooperation.”

We urge county and Knox representatives — not just their lawyers but the men who work in the highway departments and actually know what is going on — to get together to identify the problems and solve them.

For example, if it is easy to tell how much salt is in a loaded truck but hard to tell how much is in a returning truck, could a scale be installed to weigh that amount similar to the scale for trucks used at the Guilderland transfer station?

We don’t know enough about the specifics to provide a solution here. But we do know Hilltown highway departments work for the public good.

When we interviewed highway department leaders in 2018, we learned the departments regularly lent manpower or machinery to neighboring towns.

While the state was requiring the county to come up with a formal plan for shared services, which County Executive Daniel McCoy termed “an unfunded mandate,” Randy Bates, then the highway superintendent for Rensselaerville, told us that the Hilltowns have been implementing their own version of shared services for years.

“It has to be, especially with the summer months,” said Bates, explaining that this is when towns share the most equipment for tasks such as paving roads.

“It’s quite widespread,” he said.

For the good of the public they are meant to serve, we urge county and town representatives to settle their differences and work out a sensible system for tracking salt use so that the existing shed can be shared.

We surmise that buying in bulk saves money and we know that the location is convenient for both departments.

When the town of Knox has struggled in recent years just to make needed improvements to its transfer station, $50,000 or more for an unneeded salt shed is unconscionable.

It would stand as a symbol of government waste.

While we can do little to avert the national mayhem, we can work locally to see that our governments at the town and county levels use common sense to solve their differences and actually serve the public.