Conservancy works to expand Helderberg Conservation Corridor

— From the Mohawk Hudson Land Conservancy

The Mohawk Hudson Land Conservancy needs to raise another $50,000 toward its $250,000 goal of purchasing the development rights to the Heldeberg Workshop. The not-for-profit conservancy has until July 1 to exercise its option. If successful, the property would fill in another gap in the conservancy’s 3,500-acre Helderberg Conservation Corridor.

NEW SCOTLAND — When Indian Ladder Farms was placed under a conservation easement in 2003, it “was a big thing” at the time, Mark King, the executive director of the Mohawk Hudson Land Conservancy told The Enterprise in 2019. “But then, we had just an island. It quickly became apparent that we needed a broader corridor.”

So, acre by acre, donation by donation, and year by year, the conservancy worked to grow the Helderberg Conservation Corridor in the years following the easement being placed on Indian Ladder Farms.

And, if the conservancy is successful in its two current attempts at land preservation, it could add another nearly 280 acres to the conservation corridor, whose size King currently places at around 3,500 acres.

The conservancy has to raise $250,000 to purchase the development rights on the Heldeberg Workshop, King said; the not-for-profit conservancy has until July 1 to exercise its option to buy. “We’re in a final fund-raising push to meet the obligation we’ve made to the workshop,” he told The Enterprise this week.

Before the pandemic, the 237-acre workshop had hosted a summer camp, accredited by the State Education Department, on the land for half of a century.

Explaining the accounting, King said, of the quarter-million dollars his organization has to raise, $100,000 is in the form of an already-approved federal matching grant, meaning that the conservancy has to raise $100,000 to receive the federal funds; $60,000 to $70,000 has been raised through donations; the conservancy has applied for two other grants, one of which King is confident will be awarded, for $25,000.

That leaves the conservancy to raise $50,000.

King also said a $12,000 challenge is in place, which is one way the conservancy could effectively double its donations — for every dollar raised, it will be matched, up to $12,000.

King said the deal would be beneficial to both the workshop, which could use the additional funds after the pandemic deprived it of its revenue-generating programming for the past year, and to the area in general since the conservation easement would add to its “ecological value.”

The conservancy is also looking to preserve 40 acres property adjacent to the workshop, which is owned by the village of Voorheesville.

King said the village purchased the land in the early 1900s for a water system that never came to be, and that property has been all but abandoned since the 1940s.

King had thought that four separate parcels made up the 40 acres of land, which wasn’t unusual — not to know the exact boundaries of the land. “These are very old deeds and there’s a lot of forgotten history there,” he said; tax maps didn’t even come into use until the 1960s, King said.

Two of the village-owned properties are identified by Albany County Interactive Mapping, and total 20 acres. The two properties have a cumulative assessment of $4,901 — one property is assessed at $4,900 and the other at $1.

So why can’t the acreage, which likely hasn’t been thought about by any village official since Franklin Roosevelt was president, just be handed over to the conservancy?

During the February board of trustees meeting, it was noted that the village and conservancy had been in talks about the land for a year.

King told The Enterprise that he had thought the land had to be valued at something, and said he thought there was a state law for how municipalities could unburden themselves of excess land.

Richard Reilly, Voorheesville’s attorney, told The Enterprise on Wednesday that, if the board of trustees were to decide “that a piece of property is no longer needed,” it could “sell that property,” but the land would have to be sold for “essentially, fair consideration.”

Asked how fair consideration would be determined, Reilly said that an appraisal would likely be “the best way to determine” the value of the land, while noting the “unusual” nature of property, a characteristic that renders it nearly undevelopable.

An appraisal is a professional opinion on the worth of a property at a specific point in time, so, for example, if a 40-acre piece of land is nearly inaccessible from any public right-of-way, it might drop in its appraised value.

In fact, an appraisal had already been performed, it was noted during a trustee workshop Wednesday evening. The 40 acres were appraised at approximately $22,000, and the board indicated its willingness to negotiate a deal that would allow the village to keep certain rights to the land.

At their February meeting, the village trustees said that one of Voorheesville’s stipulations would be the village would retain water rights to the property in addition to “some other things” that Trustee Rich Straut was “taking a look at.”’

Mayor Robert Conway asked King if it was the conservancy’s intent at some point to have the land open to the public.

King told the mayor access would be “somewhat limited.”

Expanding on what he said during the February meeting, King told The Enterprise this week the conservancy would like to have public access, but “very controlled public access,” where visitors would be brought on the land — the conservancy has done this in the past with the permission of the village and an adjacent landowner, who provided access to the site.

King said the conservancy didn’t want to open the land to the public as if it were one of Mohawk Hudson’s preserves because the area is “kind of sensitive.”

The conservancy would want to be able to control the amount of activity that would go on at the site in part because access to the site is available only through an adjacent residential property off of Thacher Park Road, and the conservancy would look to minimize any impact on its future residential neighbor.

Conservation corridor

In 2003, Indian Ladder Farms became the first farm in Albany County to sell its development rights.

The conservation easement placed on most of the Indian Ladder property meant that the farm would remain forever agricultural. Laura Ten Eyck, manager and co-owner of the family farm, told The Enterprise in 2019 that, in the 1990s, there had been a lot of development happening in the area. Her family, which had owned the farm for several generations, wanted to ensure that, regardless of who is operating it in the future, the land could not be sold for development.

Indian Ladder Farms sold its development rights for about $785,000.

To determine the value of development rights, the land’s restricted value is subtracted from its full-market value. For example, if the full-market value of a parcel of land is $1 million, which is to say how much the land would sell for if it could be developed, but it’s determined that the land’s restricted value (its value with an easement placed on it) is $250,000, then the landowner is eligible to be paid the difference: $750,000.

In New York State, if a landowner were eligible to be paid $750,000 for his or her land, and a land trust decided that it wanted to purchase those development rights, then it could take advantage of a grant from the state’s Department of Agriculture and Markets that would pay for 75 percent of the development rights, leaving the land trust to pay $187,00.

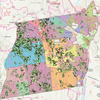

In addition to 300 Indian Ladder acres, the Helderberg Conservation Corridor is made up of about 2,000 acres in John Boyd Thacher State; about 100 acres at Locust Knoll, which is situated near the intersection of Route 85 and Picard Road at the base of the escarpment; 450 acres of state-owned Black Creek Marsh, located in both Guilderland and New Scotland; and, most recently, Picard’s Grove.

Richard Glover, a neighbor of Picard’s Grove, worked with the conservancy to purchase the 87-acre property for $665,000 in fall 2020, after a nasty legal battle that saw the property’s owner declared “incapacitated,” and an appointed attorney try to sell the land very quickly in an all-cash deal for $500,000, only to have a court-ordered appraisal find the property to have had a market value of $845,000.

King said that the conservation easement on the Heldeberg Workshop would be in perpetuity, and that the workshop would be allowed to do everything it does now, while still being permitted some growth, like being able in build a permanent structure for an office, for example, or if the workshop needed upgrade its systems and install wells, or restroom facilities, “the easement is flexible to allow that.”

One thing the easement protects is the Talus Slope and eliminates the ability to subdivide the land for development, he said.

Talus, or “debris that collects at the base of a cliff,” as Enterprise geology columnist and Heldeberg Workshop Board of Director Mike Nardacci writes, “it is a generic term, for when cliffs are as high and massive and diverse in their layered rock types as our Helderberg escarpment is — some layers being soft and thin-bedded and easily weathered, others being extremely hard and massive — they will break down and produce fragments ranging in size from clay particles to gigantic, jumbled slabs.”

“The Helderberg escarpment rises from close to the level of the Hudson River near Ravena and then moves northward on a gradual tilt that lifts it a couple of hundred or so feet per mile, reaching its greatest elevation at High Point above Altamont, where it turns west and gradually diminishes

“Its most prominent cliff is made of two layers of hard limestone — the Lower Manlius and above it the Coeymans — but those layers sit on alternating beds of relatively soft sandstone and shale known as the Indian Ladder beds and are capped by the Kalkberg and the New Scotland limestones, and other beds of shale, sandstone, and limestone. All of these layers have been subjected to millennia of attack by the forces of nature, and the result is that the escarpment sits on a talus slope hundreds of feet high.”