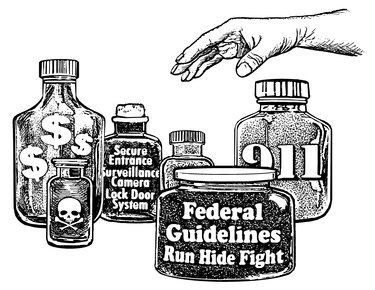

Schools need to choose the right remedies

Drills can work.

Locally, the Guilderland schools superintendent this month praised the district’s transportation department for the drills it routinely runs at each of Guilderland’s seven schools.

A high school student knew just what to do when, early one morning, the bus he was riding to school started meandering, driving on a lawn and swerving into a mailbox. The driver had fallen ill and the student knew to go to the front of the bus, check on him, pull the emergency brake, and call the dispatcher.

The kids on the bus were safe, no pedestrians or other travelers were hurt, and the driver quickly got the medical attention he needed.

A nationwide example, practiced locally, of drills that work are fire drills. On Dec. 1, 1958, a fire broke out in the basement of a Catholic elementary school in Chicago, Our Lady of the Angels. Ninety-two children and three nuns died in the fire, raising awareness of the need to practice safe and orderly ways to escape a burning school building. Several times a year, students and staff at our local schools, like their counterparts in schools across the country, practice what to do when a fire alarm sounds.

According to the National Fire Protection Association, from 1980 to 2005, an average of 1.5 people annually died on “education property” — most of them were adults or “juvenile firesetters” on school grounds after hours. No school fire has killed more than 10 people since the tragic 1958 fire at Our Lady of the Angels.

Schools across the nation now are practicing lockdowns in case of active shooters targeting them. Some schools are even holding simulated active-shooter events; one is scheduled in Voorheesville on March 24.

A problem with the local drills is they are not following the federal guidelines written in response to the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. Our Guilderland reporter, Elizabeth Floyd Mair, took a close look at the drills at local schools after covering a well-attended event for the general public, hosted this month by the Guilderland Police.

The police told the citizens about the protocol being taught by law enforcement to other police, emergency medical workers, and citizens across the country, known as “Run, hide, fight.”

When possible, the best line of defense, the protocol says, is running away from the scene and calling 9-1-1. The next best defense, it says, is denying entry to the shooter by locking doors, turning off lights, and hiding, while the third and last resort is to fight to try to overpower the attack and save lives.

Our local schools, however, are practicing only lockdowns — hiding — although for over two years the United States Department of Education has advocated the use of the “Run, hide, fight” protocol for schools.

We understand that it is much harder to run a drill where the adults in charge have to quickly decide what is safest for children and have to then develop a course of action. But that makes it all the more imperative to practice such responses ahead of time.

The federal protocol says that, if it is safe for you and others in your care, the first course of action is to run out of the building and far away. The adult in charge has to make a judgement on whether or not it is safe and then decide where the kids should run to. If it’s not safe, then the adult in charge has to get the children to hide in a place that is as safe as possible.

A drill using this protocol would stress that students and staff need to act quickly, leave personal items behind, and visualize possible escape routes ahead of time, then call 9-1-1 once they are a safe distance away.

Dr. Steven Scholozman, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and associate director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds, began his article “School Lockdown Calculus: The Line Between Preparedness and Trauma,” with a quote from a 14-year-old boy: “If there’s a lockdown and they tell me to go under the table, and there’s a window open next to my desk, I’m going out that window. There’s no way I’m sticking around.”

Scholozman goes on to examine the cost, the psychological risk to what has become a routine practice, the lockdown drill. He writes that there is almost no data on the effects these drills have on students and also that active shooters in schools are “enormously rare.”

About 20 schoolchildren, on average, suffer violent deaths on school grounds each year. Since there are about 55 million schoolchildren in the United States, that’s a one in 2.5 million chance.

We no longer learn about such events from a distance — the way, say, people read of the 1927 explosions of the school in Bath, Michigan. An angry school board treasurer there planted dynamite in the school and on his farm. After killing his wife and blowing up his farm buildings, he detonated the explosives at the school, killing 38 elementary schoolchildren and six adults, including himself, and injuring at least 58 other people.

Instead, we see terror events in schools and elsewhere unfold, again and again, in our living rooms, bedrooms, kitchens, wherever we have a screen. The danger feels more present and real.

Scholozman poses a “devil’s choice”: If we do drills to protect our students against shooters that are unlikely to ever haunt a school, then we both risk frightening our young people by planning for intentional acts of harm, thus increasing traumatic risk, and we prepare them for the rare likelihood that harm will occur, thus decreasing traumatic risk.

We grew up in the 1950s when we had regular school drills to hide under our desks to prepare, we were told, for a nuclear attack from “the Russians” or “the Communists.” As adults, we can clearly see that hiding under a desk would not have saved us from an Atom bomb.

We don’t recall feeling any safer because of those drills. What we felt was fear. We carried it around like a stone in our stomach, like the feel of a snake prickling up our back. The threat seemed everywhere with cries on the playground — “You wanna be Red or dead?” — and descriptions from our teachers of how Communists, if they took over, would make our mothers go to work like they did in Russia and we would have to be raised by the state.

We believe the drills described at the top of this editorial probably don’t traumatize kids. If your school bus is swerving, go to the front to check on the driver. Pull the break if you need to and call the dispatcher. The student working through this drill has a sense of control. The practice is discreet, for dealing with a specific instance, not part of a large and amorphous evil.

So, too, with fire drills. A walk outside on a school day often seemed like a treat, a break from routine. A fire is a known entity and practicing to escape it holds no lasting terror. Again, when you exit a building you feel active — different than crouching in fear — like your safety is in your own hands.

We urge our local school leaders and the police who advise them to review the federal guidelines and, if they plan drills, to include the “run” strategy as the first part of the protocol. Further, we urge school leaders to work closely with their staff psychologists to be sure the drills are performed in ways that are appropriate, geared to the children’s age, to ensure their well being — emotional and mental well being are as important as physical well being.

To that same point, as schools continue to spend huge sums on secure entrances, surveillance cameras, locked-door systems, and the like, we urge school leaders to consider these statistics from the federal Department of Justice crime report: 71 percent of United States teenagers between the ages of 14 and 17 have been assaulted, 32 percent have been maltreated, and 28 percent were sexually victimized at some point in their lifetime. At the same time, mass shooting incidents — killing four or more people — caused fewer than 90 deaths out of about 12,000 homicides in the United States during 2012.

We need to spend our money and efforts where the need is greatest.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer