GCSD has fewer reserves than its peers, largely due to tax refunds, says Van Alstyne

GUILDERLAND — In “setting the stage” for next year’s school budget, Assistant Superintendent for Business Andrew Van Alstyne told the school board on Tuesday that the district’s reserves are far lower than its Suburban Council counterparts.

He attributed the growing gap largely to the $5.7 million the district has had to pay out so far as the result of court challenges to town assessments.

Van Alstyne had made a similar case last January, for Guilderland to have more funds in reserve; this year, he provided an explanation, tax certiorari cases, for the widening gap.

Last month, Van Alstyne told the board, if it were to keep the same staffing and programs it has this year, next year’s budget would increase 6.1 percent from $120 million to $127 million, leaving a $1.7 million gap. Those calculations were based on the historic full restoration of Foundation Aid promised by Governor Kathy Hochul.

Van Alstyne made his presentation on Jan. 16, the same day the governor released her state budget proposal for next year, and said he had only begun analyzing the effect on Guilderland.

On Friday, he told The Enterprise that Hochul has proposed two changes for Foundation Aid.

The formula for Foundation Aid, he explained earlier, is based on the state’s calculations of how much it costs to successfully educate a student. “How much of that is the school district able to provide locally based on the income and the property value of its residents? And then what are the additional costs of high-needs students, students in economic distress, students with disabilities, English language learners?”

The first change proposed by Hochul — holding districts harmless against loss, so they didn’t have year-over-year cuts on Foundation Aid — would not affect Guilderland, Van Alstyne said.

Hochul’s second proposal — a small change in how inflation is calculated; the governor is proposing a longer term average that drops the highest and lowest year to smooth the effects of inflation — would affect Guilderland, he said.

“Ours would be slightly less than what we projected,” Van Alstyne said of the $41.3 million in state aid he had originally calculated for next year, up from $37.8 million this year.

While Van Alstyne termed that potential reduction “a concern,” he stressed that there is likely to be lobbying and legislative advocacy across to the state to see that schools receive needed funding.

Van Alstyne noted there is an online budget survey “for all stakeholders” in Guilderland, and that on March 5 the superintendent, Marie Wiles, will present a draft of next year’s budget to the board.

A primer on reserves

The state allows school districts to maintain up to 4 percent of the following year’s budget as an unrestricted, unassigned fund balance — often called a rainy-day account — but districts can also put money into various reserves or take some of their surplus to use in the following year’s budget, thus reducing taxes.

There are 13 legally permissible reserves that school districts can fund, Van Alsltyne explained to the board on Jan. 16, with rules ranging from voter authorization to board authorization for their creation and use.

He described the unappropriated fund balance as similar to household savings — “cash sitting in the bank” — to cover unforeseen expenses like damage to a house, a job loss, or illness.

Households also have savings accounts for specific purposes like a downpayment on a house, or plans for retirement or college costs, he said.

Healthy fund balances and reserve accounts “give us flexibility when unforeseen things happen …,” said Van Alstyne. “In the last 15 years, we’ve seen two major recessions. One was accompanied by a lot of federal support,” he said, alluding to the brief pandemic-induced recession in 2020.

“One wasn’t,” he said of the Great Recession, which ran from December 2007 to June 2009. “But in both cases, having that flexibility prevented very challenging decisions in the immediate onset of the crisis.”

He also noted, “Having large cash reserves also helps us save money …. The higher the credit rating we have, the less we pay in interest, which saves money and gives us stability in budget planning.”

Since reserves and the fund balance are one-time funds, Van Alstyne stressed, they should not be used to pay for recurring expenses.

Decreasing savings

Van Alstyne displayed a chart showing how, during the Great Recession, Guilderland dipped into its fund balance since the state had phased out aid to districts through the gap elimination adjustment.

With the shortfall in state aid, Guilderland cut many positions and also drew on its reserves. From 2010 to 2014, Guilderland cut over 150 full-time posts as it tried to close a gap left by stagnant state aid; declining property values; and increasing salary, health, and pension costs.

The district’s fund balance and reserves went from a total of $11.4 million in the 2007-18 school year to $5.8 million in the 2013-14 school year.

“From those challenges, we were found to be susceptible to fiscal stress by the Office of the State Comptroller in 2012-13 and 2013-14,” he noted.

That, in turn, caused Guilderland’s bond rating to be lowered. “It has since rebounded,” said Van Alstyne.

“Finally,” he said, “you have fewer options for balancing the budget when your reserves are lower because the state has a tax cap on the property tax levy increase.”

Guilderland currently has an unassigned fund balance near the state-set 4-percent limit of roughly $4.8 million while its reserves total about $6.2 million.

The largest reserve, of about $5.3 million, is for retirement contributions, which Van Alstyne said “will come in handy because the interest rates are quite variable because they’re largely determined by the performance of the stock market.” When the market does well, the rates go down.

Guilderland also has a capital reserve of about $74,000, a reserve of about $130,000 for employment benefit liability, an unemployment reserve of about $65,000, a reserve for repairs of about $61,000, and a workers’ compensation reserve of about $611,000.

The district’s tax certiorari reserve is currently at zero since Guilderland has been forced to pay it down, and take out bonds besides, to meet the requirements from court decisions on tax cases.

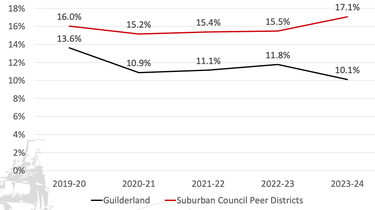

Van Alstyne also displayed a graph comparing Guilderland with its Suburban Council peer districts for the last five years. The Suburban Council is an athletic league made up of districts comparable to Guilderland.

“We see our peers have seen a moderate uptick, so they’re not at 17.1 percent whereas we have experienced a decline in our fund balance and reserves,” he said.

If Guilderland funded its reserves at the same level as its Suburban Council peers, Van Alstyne said, Guilderland would have to have an additional $8.43 million.

This gap, which grew by over $4 million in the last few years, he said, “is notable because we’ve paid out $5.7 million in tax certiorari refunds so far, right? So that is by far the single biggest explanatory variable in understanding why our reserves are smaller than our peers.”

There are also general factors that are affecting many school districts, Van Alstyne said, such as challenges from the pandemic, inflation, and increased costs for transportation and health care.

“Those are hitting our district,” said Van Alstyne, reiterating, “and then the specific factor … we have paid out $5.7 million in tax certiorari claim refunds and face an additional significant refund with Crossgates, which is still in the midst of being finalized.”

Van Alstyne stressed the importance of having reserves to “smooth out our year-to-year budgets. With financial challenges, reductions have to come somewhere,” he said. “The tax cap constrains our levy increases.”

He concluded, “And finally, having a strong tax base and having strong schools is a key contribution to a vibrant community with rising property values.”