Comptroller says: Guilderland School District is 'susceptible to fiscal stress'

Enterprise file photo — Melissa Hale-Spencer

Neil Sanders, the assistant superintendent for business at Guilderland, says schools in New York State are getting mixed messages. “We have a dichotomy between the governor and the comptroller,” he said. “The governor says school districts have money in fund balances and reserves that need to be used to solve budgetary problems. The comptroller is saying, if you use up your reserves, be careful because you’re putting yourself in fiscal stress."

GUILDERLAND — The suburban school district here, long thought of as a low-need or wealthier district, is among the 13 percent of districts statewide that the comptroller has designated as being fiscally stressed.

In a report released on Jan.16, Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli categorized 12 districts — out of 674 across New York — as being under “significant fiscal stress,” 23 were under “moderate fiscal stress,” and 52, including Guilderland, were “susceptible [to] fiscal stress.”

The remaining 587 districts received no designation.

“While low-need districts are often considered wealthy, resource-rich communities, they are also prone to fiscal difficulties — with 9.6 percent of these districts experiencing fiscal stress to some degree,” states DiNapoli’s report.

Following this trend, another school district in Albany County to be designated was the suburban district of South Colonie, deemed, like Guilderland, to be “susceptible [to] fiscal stress.”

Elsewhere in the county, districts typically considered as more high-need than South Colonie or Guilderland — like the city districts of Albany, Cohoes, and Menands or the rural districts of Ravena-Coeymans-Selkirk or Berne-Knox-Westerlo — received no designation.

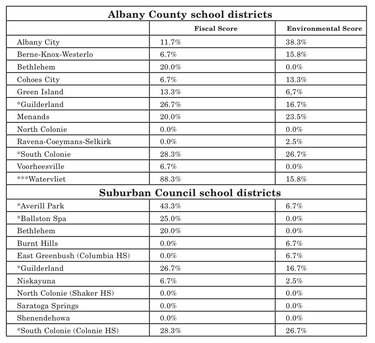

Four of the 12 Suburban Council school districts, generally considered low need or wealthy, are listed by the comptroller as being “susceptible [to] fiscal stress.” (See chart.)

At the same time in Albany County, Watervliet, a city district thought of as high-need, had the highest indication of fiscal stress in the state, at 88.3 percent, and was one of the dozen labeled as being under “significant fiscal stress.” (See chart.)

“We have a dichotomy between the governor and the comptroller,” Neil Sanders, the assistant superintendent for business for the Guilderland schools, told The Enterprise this week. “The governor says school districts have money in fund balances and reserves that need to be used to solve budgetary problems. The comptroller is saying, if you use up your reserves, be careful because you’re putting yourself in fiscal stress. They are mixed messages.”

Sanders went on, “Our approach has always been about balance…balancing gaps and reductions against resources. We don’t like making reductions; we like to preserve programs.”

He concluded, “We’ve been open with the board and the community. We’re not using up all our resources and taking the easy route.”

The comptroller’s report, based on a year of data, Sanders said, would not change Guilderland’s approach to budgeting. “We’ve been eating into our fund balance and reserves,” he said. “We’re well aware of what we’re doing…These are indicators not determinations of fiscal stress,” Sanders said of the report’s numbers.

By the numbers

The stress scores are based on information school districts filed with the State Education Department in December.

Guilderland’s fiscal score of 26.7 percent is at the “bottom end” of the susceptible-listing threshold, according to Jennifer Freeman, a spokeswoman for the comptroller’s office. (Locally, BKW and Voorheesville each have a fiscal score of 6.7 percent.)

“The higher the number, the more susceptible a district is,” said Freeman.

Asked how the scores were arrived at, Freeman said, “Our auditors and local government fiscal experts took a number of factors into account.” Among those is the size of the district’s fund balance, or rainy-day account, which, by state law, is required to be under 4 percent of the annual budget. Another factor, said Freeman, is how much short-term borrowing a district has done, and a third is whether a district has overridden the state-set tax cap.

DiNapoli’s report says the system’s financial indicators are based on seven different calculations in these four categories: year-end fund balance, operating deficits, cash position, and short-term debt.

Each calculation is linked to a point-based scoring system and drives an overall financial indicator score with the potential for a total of 21 points. If a district receives 65 percent of the total possible points or more, its fiscal stress is deemed significant. If it receives 45 percent or more, it is labeled as being under moderate fiscal stress, and if, like Guilderland, it receives 25 percent or more, it is called susceptible to fiscal stress.

“We’re on the cusp,” said Sanders, noting how close Guilderland’s 26.7 percent is to the 25-percent cut-off. He likened it to a student with a score of 65 percent passing while a student with a score of 64.9 percent would fail a course.

“You have to draw a line somewhere,” said Sanders.

Guilderland’s fund balance is at $2.4 million, or 2.6 percent of its budget, according to Sanders. “We’re $1.3 million under the maximum permitted by law,” he said, noting the comptroller would like to see a larger fund balance.

For several years in a row, before the 2008 recession, Guilderland was cited in its annual state-required audit for having a fund balance that was higher than the percentage allowed by law; a majority of board members at the time felt that was prudent so that the district could be prepared for an emergency and also could meet payroll without borrowing if state aid payments were delayed.

After the recession, the board was willing to use more of the fund balance to keep the tax-rate down and to avoid cutting more staff and programs.

“We’re well aware of the fund balance; we talk about it every year,” said Sanders. “We’ve been open and up front about balancing the fund balance against resources.”

Since the tax-levy cap was instituted two years ago, Guilderland has not gone over it, which would require 60 percent rather than 50 percent of the vote. Last May, the $91 million budget for 2013-14 passed with nearly 64 percent of the vote.

In addition to the size of the fund balance, the other factor the comptroller’s indicators homed in on, Sanders said was Guilderland’s cash position or liquidities score.

The comptroller’s office devised a threshold for cash on hand when compared to monthly expenditures. Total expenditures were divided by 12 to come up with a monthly average.

“Then they saw how much a district had on hand at the end of the year,” said Sanders, noting that Guilderland had 99.5 percent of covering that monthly average.

It needed 100 percent or more not to get red-flagged. Sanders said that, if Guilderland had had just $38,410 more in its cash balance at the end of the year, it wouldn’t have been red-flagged.

“Outside the district’s control”

“The flip side is the environmental score,” said Freeman.

Guilderland’s is 16.7 percent, BKW’s is 15.8 percent, and Voorheesville’s is 0.0 percent. That score is based on such factors as the number of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, and the homes in the district below the statewide median price, Freeman said.

The environmental indicators, DiNapoli’s report says, capture “those circumstances and trends that are largely outside the district’s control but which have a bearing on its revenue raising capabilities as well as its demand for and/or mix of services.”

The environmental indicators are based on six calculations in these five categories: property value, enrollment, budget vote results, graduation rate, and free or reduced-price lunch.

Sanders noted that Guilderland underwent “a change in property values”’ last year. “There was a decrease in property value in Guilderland for the first time,” he said.

He also noted that the district has declining enrollment; currently about 4,900 students attend Guilderland schools.

The report stresses overall, “This system measures the level of fiscal stress a school district is facing, not its level of fiscal health. A district’s absence from the top three categories should not be viewed as substantiation of good financial condition by OSC.”

No “easy” decisions

At the same time the comptroller’s office has run numbers on the close to 700 public school districts in the state, it has also come up with similar numbers for the state’s 4,000 or so municipalities, said Freeman.

DiNapoli’s monitoring last year identified 40 municipalities — including 16 counties, 18 towns, five cities, and one village — in some level of fiscal stress. Later this year, the comptroller’s office will release more scoring lists for municipalities. (The comptroller’s Jan. 16 report on schools did not include the “Big Four” dependent school districts — Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, and Yonkers — as they do not have the separate authority to levy taxes. These districts will be included in the scoring for their cities.)

The comptroller’s recommendation for fiscally stressed municipalities, said Freeman, is consolidation.

“For schools, it’s tougher,” she said. “The fund balance, by law, is low.” She also noted that the tax-levy limit, which, with a complex formula to adjust it, is set at 2 percent, or the cost-of-living increase, whichever is lower. So, with the lack of inflation, the cap is now at 1.45 percent.

“The margins for school districts are getting smaller,” she said. “If there is a way to manage red-flag areas, it may be to partner with other school districts, to share services or consolidate.”

She concluded, “School districts have sophisticated financial operations…The decisions for schools are not easy.”

“A critical barometer”

In the last four years, Guilderland has cut 153 full-time posts as it tries to close a gap left by stagnant state aid, declining property values, and increasing health and pension costs.

For the upcoming 2014-15 school year, using a roll-over budget — that is, if programs and staffing were to remain the same — Guilderland is facing a $2.4 million gap.

DiNapoli’s report on school districts’ fiscal stress found, not surprisingly, that high-need urban and suburban school districts were three times more likely to be considered in fiscal stress compared to low-need districts. But, it also found that high-need urban/suburban districts were 2.5 times more likely to be fiscally stressed compared to high-need rural districts and three times more likely when compared to low-need districts.

“Interestingly,” the report states, “high-need rural districts were slightly less likely than average-need districts to be in fiscal stress.”

Upstate districts were more likely to be stressed than downstate districts. The highest number of stressed districts were in central New York, followed by the North Country, and then western New York.

Many districts, the report says, have experienced declining property values as well as declining enrollment, leading to budgetary strain, indicative of a declining tax base. As a result, tax rates may need to increase simply to maintain existing levels of property tax revenues.

“Generally,” the report says, “low-need districts, while having greater property value on a per pupil basis, also experienced the greatest decline in property value compared to the other need/resource categories.”

Small, high-need rural districts have had the highest enrollment decline.

DiNapoli called school districts “a critical barometer to the fiscal health” of local communities.

His report states that New York’s schools “are facing severe fiscal challenges.”

It goes on, “District officials must continue to improve student performance, ensure student safety and provide extracurricular activities that taxpayers value for their children — all against the backdrop of a slow economic recovery in which resources are limited.”

The report concludes, “Education is one of the most important functions that localities provide, and it is also one of the most expensive. School districts provide the foundation for the success of future generations, and do so in the midst of close scrutiny by taxpayers and mounting fiscal pressures….

“Schools are facing fiscal challenges that are not likely to dissipate in the short term. Between a tax levy limit that restricts local funding, State and federal aid cuts and a lack of other sources of funding, schools are in a period of low revenue growth. These challenges underscore the importance of fiscal monitoring and the need for swift action on behalf of all parties to safeguard the fiscal health of the State’s school districts.”