Ray Wood finds the serviceman fathers of half-Vietnamese children

GUILDERLAND — Immigration attorney Ray Wood has an unusual hobby: He reunites Amerasian children of American servicemen with the fathers they never knew.

Van Nguyen, owner of Van’s Vietnamese Restaurant at 307 Central Ave. in Albany, says that he now has everything, because Wood found his father a year ago, when Nguyen was 47. Nguyen was able to visit with his father — Charles Garner Jr. of Shippensburg, Pennsylvania — several times and introduce him to his own wife and children before his father died last summer at age 74.

“For most of his life, he had no idea where his dad was. Turns out he’s five hours away. They talked and they bonded,” Wood said.

Nguyen even brought his mother, Dua Tran, with him to see Garner, and the couple were as loving toward one another as if 47 years had not gone by.

Garner would tell everyone, said Nguyen’s wife at their restaurant Monday, “I got my girlfriend, Vietnamese, she’s beautiful!”

Nguyen is one of about 30,000 Amerasians who came to the United States after the passage of new legislation that paved a way to citizenship for children whose fathers were American servicemen.

Charlie Woelgesy, a half-Vietnamese man who did some carpentry work in Wood’s house, asked Wood to help him get a passport.

This meant helping him to become a citizen, Wood said, and he began trying to track down the man’s father. It was relatively easy because the father’s last name — which Woelgesy had started using when he arrived in the United States — was unusual.

Charlie Woelgesy’s father was dead but had been a competitive swimmer, Wood said. Wood was able to find newspaper articles about him throughout his life, many with photos.

Wood found many articles, he said that “I could almost raise this guy from the dead and say, ‘This is who your dad was.’”

Charlie Woelgesy cried when he learned his father had been found, Wood recalled.

Nguyen was a friend of Charlie Woelgesy’s and heard from him about the work Wood had done. Nguyen, too, had been told a name for his father, but it was a common one: Garner.

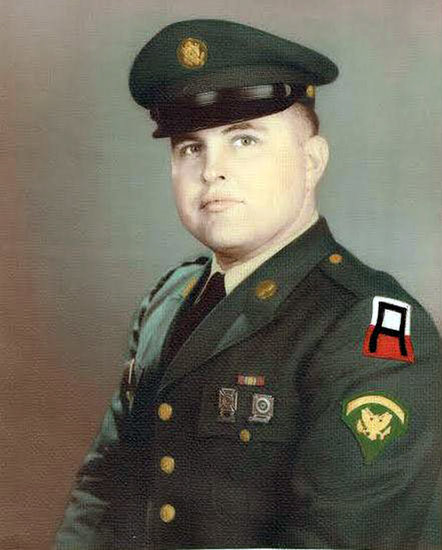

Young serviceman: Charles Garner gave this photo of himself in uniform to Van Nguyen’s mother almost 50 years ago, but she lost it during one of the family’s moves to escape the Viet Cong. The Army gave a copy of it to the family at Garner’s funeral in August 2018.

“Half and half”

Nguyen’s childhood in Vietnam was not easy. He knew nothing of his father. His mother never spoke about him, and children in Vietnam did not make a habit of asking their parents probing questions, he said.

Whenever he went out into the street, Nguyen said, he would be called “half and half.”

“They kept calling me Amerasian in school, and I fight a lot,” Nguyen said. “I just knew I was different.”

Amerasians had to fight, Wood said, to survive. They would be bullied at school, if they were allowed to go to school. Often, he said, they would be kicked out.

Vietnamese people have dark skin, Nguyen said. His own skin was “too light.” His mother used to rub mud on his skin when he was a child, to hide his ethnicity.

His mother had had one child before Nguyen and then split with that child’s father, but she returned to him after the war ended and Nguyen’s father had left, and they had six more children. Nguyen was singled out by his stepfather for harsh treatment, Wood said, including being hung by a rope from a tree for the slightest infraction.

After the war ended, Nguyen said, the Viet Cong would search for Amerasians and would kill them if they could find them.

His mother moved him from one place to another, Nguyen said. “Moved me couple places because she’s got to hide me. Town to town. Afraid of the government looking to kill me. After the Americans left, they were looking for people to kill.”

But she never told him anything about his father, until after she learned of the new American legislation that would allow him to go to the United States.

“She said, ‘You can come to the United States, because you have American father,’” Nguyen recalled.

Seven years after he first applied, in 1992, Nguyen was allowed to came to the United States and given a green card. He became a citizen a few years later, and was able to bring over his mother and most of his half-siblings.

Back then, Wood said, the way that the American embassy officials in Vietnam would decide if someone was Amerasian was by looking at them. “This was before DNA,” Wood said. “The first way they determined was, ‘Let’s have a look at you.’”

Nguyen started working on his seventh day in the United States, as a dishwasher at the Steuben Club in Albany.

Nguyen always watched the chef, Wood said, memorizing how he did things. So one day, when the chef didn’t show up, he said, “I can do everything he does. Plus you can get rid of these other two, because I’m going to do their jobs too.”

And he was the chef for years, Wood said, and they loved him. “Eventually he opened up his own restaurant and it’s very popular. It was just his aptitude.”

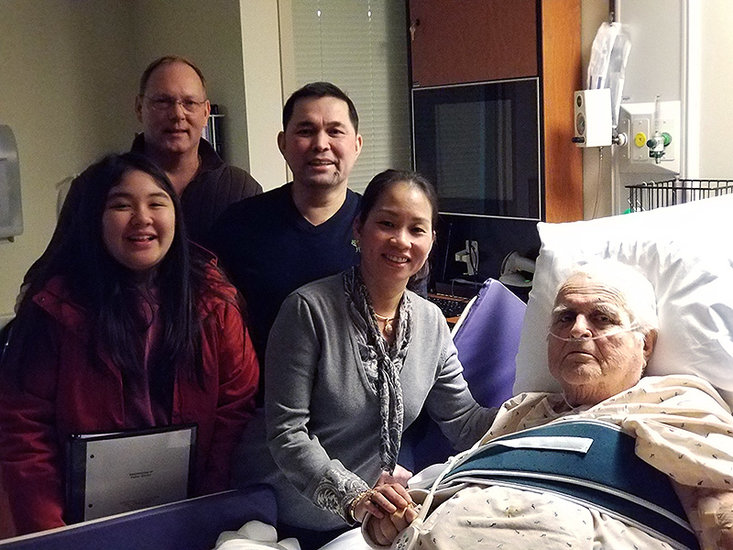

First meeting: On New Year’s Day, 2018, Amerasian Van Nguyen and his family meet Nguyen’s father for the first time. From left are Emily, Nguyen’s daughter; attorney and friend Ray Wood; Van Nguyen; Nguyen’s wife, Tho Tran; and Vietnam veteran Charles Garner, Nguyen’s father.

A father found

Wood had Nguyen take a DNA test, and Wood uploaded the results to Ancestry.com, to 23andMe, and to Family Tree DNA — different genealogy websites that use DNA to connect relatives.

“Fishing in different ponds,” Wood said of using a number of sites.

Wood knew that Nguyen’s father might not have uploaded his DNA to any of the websites, but that a second or third cousin might have.

For each new hit, he would make a complete family for the new-found relative and try to uncover more connections, using a variety of databases. Obituaries are a good source for locating names and family connections, to create new leads, he said. He also looked for old newspaper articles about family members.

A lot of matches were coming up from the Shippensburg, Pennsylvania area, he said.

One day in December 2017, when Wood had narrowed the search to a few men from the Fayette, Chambersburg, and Shippensburg area, Wood went to Pennsylvania to start knocking on doors.

“You have to sell it,” Wood said, “and you only have a few seconds.”

His approach, he said, was to immediately hand over the man’s family tree and say he had been working on it, and to show the old news articles he had found about his relatives.

“That blinds their reason, delays their reason,” Wood said. “It stops them from thinking, ‘Yeah, but why are you here?’”

He had knocked on three or four doors already when he got to Charles Garner’s home in Shippensburg. His heart “quickened” when he saw the American flag and the United States Army flag flying on separate flagpoles in front of the home, as well as the license plate that read “Disabled American Veteran.”

Wood was thinking that this was going to be difficult, when he saw that the door was open and heard Charles Garner call out, “Come on in!” His little dog had alerted him to Wood’s presence.

“He’s like Van,” Wood said of Garner. “Van’s a very big-hearted guy.” Charles Garner didn’t ask why he was there, but looked over the documents Wood gave him with interest.

Wood asked him, “Were you ever in the military?” and Garner said he had been in Germany and Vietnam.

Where in Vietnam, Wood asked. “Pleiku City,” said Garner. That was where Van Nguyen was born.

“So the next objective,” Wood said, “is to learn all I can about him, because what if he gets mad and throws me out?”

He learned that Garner had two daughters, no sons. One of the daughters was still alive, but one had died in an accident when she was a child, driving a ride-on kids’ car into the street.

In addition to his daughter, Garner had one former stepdaughter, from his second marriage; he had been divorced twice over the years.

Wood pressed ahead, asking Garner, “Did you have any relationships while over there?”

Garner said, “Oh yeah, I had this one, she was a mountain girl.”

Wood remembered that Nguyen had said his mother came from the mountains. He said, “What would you think if I told you you might have a son?”

Dead silence. Then Garner said, “Well, it could be.”

Wood told him he did have a son, and asked if he would mind if Nguyen came to visit him.

Still unsure if Garner would change his mind and never let him in again, Wood asked if it would be OK to take a picture of his chihuahua. He then took a selfie, with the dog in the center of the frame, and with him on one side and Charles Garner on the other. In the picture, the chihuahua is licking Wood’s ear.

“I pull out, drive half a block, and text Van the picture. Can you imagine? I send him a text with his father’s name and a picture of me and his father and the dog.”

On New Year’s Day, Wood went with Nguyen, Nguyen’s wife, and Nguyen’s daughter, Emily, to meet Charles Garner. Garner was in the hospital because he had fallen and broken his arm. He also had diabetes and needed dialysis several times a week.

At their first meeting — where Wood said they were able to observe Garner talking with nurses and others and to see that he had a sense of humor — Nguyen wasn’t sure Garner was really his father.

Nguyen had tested him, asking him to tell him his mother’s name. Garner said “Ly” (pronounced “Lee”).

That isn’t right, Nguyen said. After they left, he called his mother and told her of his doubts and asked her what Garner used to call her.

His mother said that she gave him a nickname for her, “Ly.”

The next day, the whole group went back to the hospital again. Charles Garner had been up all night, he told them, trying to remember, and had come up with “Dua.”

But it didn’t matter. “That time I believed already,” Nguyen said.

The family went back on Easter, with Nguyen’s mother. “The body and the hair changed, but she knew him,” Nguyen said.

He continued, “When he saw her, he looked like he went back to 20 or 21; he fell in love again.”

She fed Garner, Wood said, and tidied his house and did his laundry while they were there, as the two of them bantered and reminisced.

Nguyen and his family visited Garner again in July and then went once more in August, after he had had another bad fall, just days before he died. Hospital staff had warned them that he might not wake up and might not recognize them.

As soon as they walked in the room and said hello, Nguyen said, his father woke up and said, “Hi son! Hi Ly, come give me a kiss.”

He was unable to speak after that, but Nguyen said he would grip their hands back and they could see a trail of tears on his face.

Between Easter and the time he died, Nguyen said, his father called his mother every day. She has 75 voicemail messages from him, he said.

Nguyen’s mother presses play on her phone, and Charles Garner’s voice — cheerful, confident — booms out. “Hi baby, I just wanted to say I love you.”

She listens to his messages before she goes to sleep, Nguyen said.

“And I look at the picture,” his mother said, displaying a picture on her cell phone of a young Garner in his Army uniform.

Nguyen and Wood had not known why Nguyen’s mother told Garner, in Vietnam 47 years ago, that the child wasn’t his. They learned this week that she had initially told him yes, she would go with him to the United States.

She looked through his wallet, she said, and found photos of him with a woman and two small children, and realized he had a family there. She didn’t want to break it up, she said.

Now, thanks to DNA, voicemail, and Ray Wood’s efforts, it doesn’t matter.

After finding his father, Nguyen is content and has everything he ever wanted, his wife says.

“Yes, everything’s over now, in here,” Nguyen says, placing his hand on his heart.

As a veteran himself, Wood also finds satisfaction in helping other veterans. He says of Garner, “It made him very happy. He got the son he never had.”