It is never too late to say 'thank you'

“Gratitude is a fruit of great cultivation; you do not find it among gross people.”

— Samuel Johnson, as quoted by James Boswell in Tour to the Hebrides, 1785

We admire Ed Ackroyd’s diligence. He came to our newsroom last year as he searched for local soldiers who were killed in action. He’s put together a plaque to honor them at the Altamont Post of the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

He came by our office this week to show us two certificates, each in a sapphire blue case embossed with a commemorative seal noting the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War. Around a map of Vietnam are these words: Service, Valor, Sacrifice.

Inside one case was a certificate to honor Margaret Gilbert. Her son, Glenn, died in Vietnam on Aug. 4, 1970. Inside the other was a certificate to honor Glenn Gilbert’s sister, Patricia Wagoner.

Over the decades, Mrs. Gilbert, dressed in crisp white, right to her gloved fingertips, has been a familiar sight locally as a Gold Star Mother, riding in parades or placing Memorial Day wreaths. We’ve run her picture in our newspaper many times.

But, as we looked at the words on the certificate, we weren’t sure of the news value.

“On behalf of a grateful Nation and the Department of Defense, we are proud to recognize and honor your loved one, you, and your family for the significant sacrifices made in the name of freedom and democracy,” said the paper signed by both the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “Thank you for your example of grace, dignity, and courage….”

What was there to report? Where was the news? We thought that, after decades, a few words would make little difference, bring scant comfort.

We were wrong.

We found out when we called Mrs. Wagoner just how much that thank-you meant.

“It was a total surprise to me,” she said of the presentation at the Gold Star Mothers’ luncheon held after Albany’s Veterans Day Parade last Monday, Nov. 11. The presentation was made by Joseph DeFrancisco, a retired lieutenant general who served as the grand marshal for the parade.

Mrs. Wagoner named the many local dignitaries who were at the luncheon when she accepted her certificate and a certificate on behalf of her mother who is suffering from Parkinson’s disease and was unable to attend.

Mrs. Wagoner reminisced about her girlhood on her family’s Hilltown farm. “It was just my brother and me,” she told us. “We were very close. We fought like cats and dogs like any brother and sister. But we were right there to protect each other when needed.”

She recalled how she failed her first driver’s test in the family’s Rambler but, when her brother, who was two years older, lent her his prized 1965 Mustang, she passed with confidence.

“He took me out for my first drink when I was 18,” she said.

After Glenn Gilbert graduated from Berne-Knox-Westerlo in 1966, he worked on the farm and also as a bartender for Mr. Ackroyd’s father at the Wayside Inn on Thompsons Lake Road.

He was drafted into the Army. “He didn’t fight it, like some others did,” said his sister.

After completing basic training, he got orders to go to Vietnam. “He was a foot soldier,” said his sister. “He wasn’t there a month when he came up missing in action.” She said that helicopters were dropping supplies near a river and he went into the water to retrieve some. “He got caught in the undertow,” she said. “He didn’t know how to swim.”

Representatives from the Army came to the Hilltown farm to tell the family that Glenn was missing in action. “Then, later, they came again to tell us he was dead. Once is bad enough,” said Mrs. Wagoner, her voice trailing off. “It was hard. It was unreal.”

No one ever said thank you.

Until now.

That’s why it meant so much to Patricia Wagoner and her mother, after all these years.

She said, at the time, “with all the protests,” even soldiers who had survived the war often hid their service. “When the soldiers were coming back, some of them changed into their street clothes on the plane,” she said. “I’m glad that’s not happening to soldiers now.”

Mrs. Gilbert has been an active member of the Gold Star Mothers all these years, her daughter said, because her sister sufferers were the only ones who truly understood her loss. “They have their times of tears but they also have lots of laughter,” she said of the Gold Star Mothers.

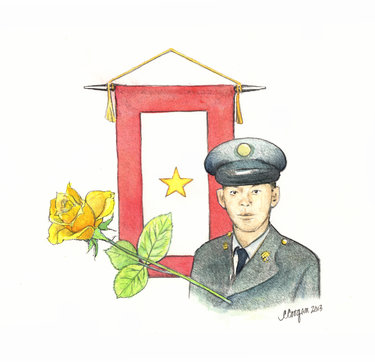

The stars were proudly displayed on banners: blue for sons who served, gold for those who died.

“Anyone who says, ‘You’ll get over it’ is wrong. You don’t,” said Mrs. Wagoner. “People come up to you and say, ‘I’m so sorry. I know how you feel.’ But, actually, they don’t. It’s hard to explain….”

Mrs. Wagoner said she was speechless, too, when she received the certificate from the parade’s grand marshal on Veterans Day.

“I never expected anything like that. The tears came. It meant so much.”

She said the certificate means an awful lot to her mother, too.

“It’s nice to have someone say, ‘Thank you very much. Your loss matters.’”

And so we’ll add our thanks to those of the Secretary of Defense. We’ve long believed it is possible to object to a war while still respecting the warrior.

A young man, before he had even decided on his life’s course, was plucked from his home only to die in service.

We can’t pretend to know his family’s loss but we can learn from our ignorance in thinking a statement of thanks more than four decades after a soldier’s death wasn’t newsworthy.

Here’s the news: Saying thank-you matters.

Our advice: Take those words and utter them to those you believe deserve it.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer